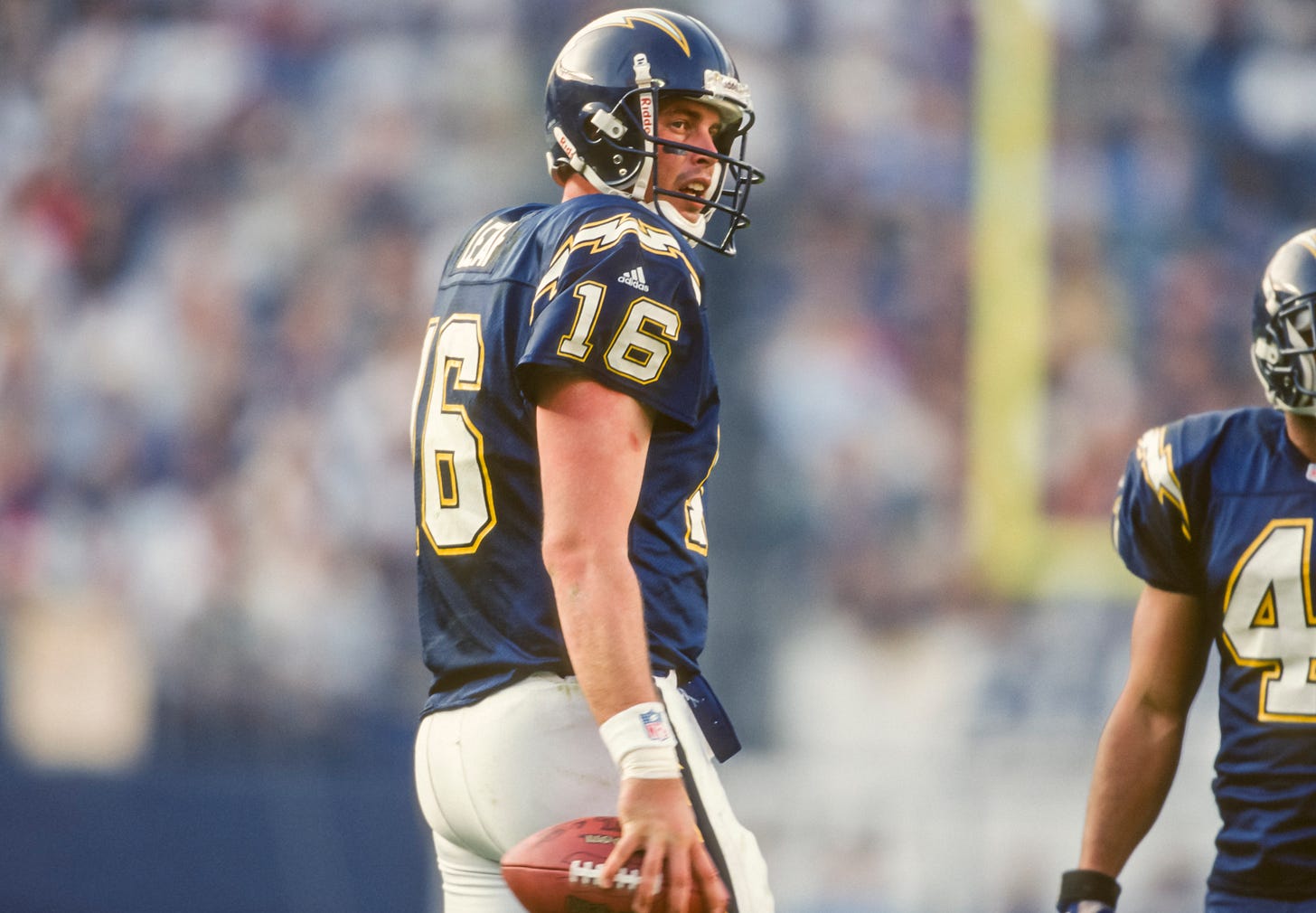

Part II: What happened to Kevin Kolb?

Concussion No. 4 didn't only send the quarterback into retirement. He slipped further into depression. How Kevin Kolb escaped this darkness gives hope to the sport itself.

Miss Part I? Catch up here.

Start in the morning with how we all get going.

A cup of coffee.

After Concussion No. 4 ended his pro football career, Kevin Kolb stayed in Western New York for testing and to help rookie E.J. Manuel any way he could. He’d pick up a coffee and — if he consumed too much caffeine? — the retiring quarterback would spiral the second he came down from the high. Caffeine, he says, “exaggerated everything.” He’d feel spacey. Drifted. Start chugging water to offset the caffeine in his system. Even slip a dip of tobacco into his lower lip because research told him nicotine stimulates the brain. Very quickly, Kolb learned this was a rough combination.

“It was bizarre,” Kolb says, “trying to coordinate all of that all the time.”

His memory flickered. Once at the wheel, he needed to ask his daughter how to drive to her preschool.

His sleep suffered. In bed, he’d stare at the ceiling for four hours straight.

His vision blurred. When he read more than three pages of the Bible, words blended together. When he brushed his teeth in front of the mirror, a cloud would form around his face like those Washington Redskins fans in the stands. He’d be jacked up for a solid three hours, too. The sensation was disturbing.

“Like you are walking through the world,” Kolb says, “but you don’t feel part of the world. You feel like you’re just watching everybody. Almost like you’re high. But it’s scary. You’re scared. You don’t even know what’s going on, but you’re walking through life normal. Everybody thinks you’re normal but you’re in a different zone. You’re in a different area. And then whenever it comes back or you get locked in or somebody clicks your focus back in, you’re like, ‘Oh! What just happened the last two hours?’ Or, ‘What just happened at that last stop sign.’ Or, ‘I just forgot where my kids go to school.’ And then fear sets in: Do I tell anybody? What am I supposed to do?”

He wanted to babysit his daughters, to give Mom a break, but this hazy realm of existence became a danger. He could space out for a brief 2 minutes.

The moment Kolb came to, he panicked.

“Like, ‘Oh my gosh, Did I just run my child over when I pulled out of the driveway? Did she just go down to the lake when I wasn’t paying attention?’ When you have those drift-in-and-out moments, my kids were where my real fear was. Because they were all at the age of one to two to eight at that time.”

There were thankfully no such close calls.

Kolb did, however, nearly kill himself.

This memory’s been buried in his mind for 7 1/2 years. Kolb admits he hasn’t even thought about this close call since we last talked. But upon hearing Southwestern Boulevard, the images rush back to him. Yes, Kolb was driving from his home in Lake View to the Bills facility in Orchard Park. After spacing out — “dazed” and “drifted” — he glided over the center line at around 55 miles an hour with an oncoming vehicle only 45 yards away. Back in ’15, he said the other driver reacted. Today, Kolb thinks he corrected over himself.

All Kolb remembers are the six words that immediately crossed his mind upon surviving: What in the hell just happened?

Life without football was off to the worst imaginable start.

Go Long strives to be your home for longform journalism in pro football. Subscribers get all profiles, all team deep dives, all columns, all podcasts, all chat access:

Concussion No. 4 predictably torpedoed the 2013 Buffalo Bills. Through a 6-10 season, Manuel struggled. Starting so soon stunted the rookie’s career beyond repair, re-routing the franchise’s search for a franchise quarterback yet again. Manuel never recovered. (Take it from him.) Yet the concussion also torpedoed Kolb’s life in ways he never expected. He visited every possible expert. The first to truly listen was more of a “crazy witch doctor” in Boston, Mass., who advised Kolb live his best possible life: eat right, sleep well, stay disciplined.

Wise words considering these symptoms lasted eight excruciating months.

“I’d fly to the top,” he says, “and then I would fall to the bottom.”

Kolb stayed in Buffalo until Halloween. The next day, his family flew south to their ranch in Guthrie, Texas to reset. They planned on locking down in serene seclusion for an extremely long period of time. After all, Guthrie is the headquarters of the famous “Four Sixes” Ranch. Three months in, Kolb told his wife, Whitney, he was ready to return to their home in Granbury about 3 ½ hours away. Whitney could tell Kevin was wrestling with something but he wouldn’t say. Not yet.

As Kolb took his family back to their lakehouse this rainy day in January 2014, around 2 in the afternoon, he couldn’t hold back his emotions any longer. The finality of his football career was clobbering him with more force than any blitzing linebacker. Now, it was real: Kolb would never throw a pass in the NFL again. His spirit was “ripping.”

His wife was asleep. His daughters were asleep.

Whitney woke up to the sound of her husband’s tears.

“What’s going on with you?” she asked.

“That’s what I lived my whole life for right there,” Kevin answered. “That was it.”

He was only 29 years old. With millions of dollars in the bank. With a beautiful home waiting for him at the end of this drive. With these three beautiful daughters in the backseat and a fourth in the future. But football was forever this man’s reason to wake up in the morning. Strip it away so abruptly and — as Kolb says — it doesn’t matter if you’re prepared or not: “You fall off a cliff.” Many of the sport’s virtues helped, immensely, but Kolb quickly learned that football alone didn’t prepare him for day-to-day life.

The football gods essentially tore off his skin and ejected him into a whole new world.

No concussion symptom felt as bad as this feeling of being deceived.

“I was completely unsettled,” says Kolb. “Everything I had been through for 10 years was condensed down to that one moment. That was the turning point — ‘Are you going to fight it? And live your life in a miserable fashion? Or are you going to repent?’ To say, ‘I’m here Lord. I’m yours. I’m not going to do it my way anymore. You let me run to the end of my leash.’ In my case, the leash was wealth and I got it all. I had it all. And it proved to not be enough.”

That drive, Kolb wiped away his tears and admitted he needed to change.

“Are you going to come with me?” he asked his wife.

“You know I am.”

The next morning, he started a new life.

At 5:30 a.m., Kevin Kolb knocked on a neighbor’s door at Granbury Lake. This was the one man he knew lived with integrity, purpose. The neighbor greeted him in a robe and Kolb cut to the chase: “Just show me how to live.”

While it might’ve felt like he had a million friends as an NFL quarterback, he really didn’t. Kolb admitted he was lonely. He had nobody he could “come clean” with, nor any clue how to walk out a life of character, of living for a higher power. This two-hour conversation was a religious awakening. Step by step, the man showed Kolb how he reads the Bible, and prays with his wife, and the best way Kolb can explain it? He needed to peel back the onion of how he was trained to live as a coach’s son, as a quarterback the last 20 years.

Kolb’s mind began to calm.

His brain, of course, still required assistance.

Not that this was high on the NFL’s priority list.

He didn’t need the money but — considering football was responsible for his brain damage — Kolb sought permanent disability in 2014. It didn’t go well. As former Packers quarterback Don Majkowski detailed to Go Long, these trips to NFL-appointed doctors often morph into “deny and deny until you die.” Other retirees warned Kolb: Say this to that doctor, they’d explain, and you’re screwed. So many are experts in doing the NFL’s bidding. Visit to visit, it felt like nobody was taking Kolb’s health seriously. They’d check his knees… his arms… his chest… before Kolb would cut in. “Hey, it’s my brain, guys!” At which point, one doctor asked if Kolb traveled by airplane. He said he did and the doctor deduced that this must mean he’s A-OK, which Kolb found puzzling since somebody else booked his ticket. Not to mention, those flights sent his brain into a weeklong “whirlwind.”

Whatever. He traveled by car to his next visit, in Houston, a 550-mile roundtrip. This doctor said that if he was able to drive for eight-plus hours, well, he must be fine.

With that, Kolb waved the white flag. He didn’t know what game the NFL was playing but they sure as hell weren’t going to do it with his brain.

Chasing a check wasn’t worth the hassle.

Adds Kolb: “I felt like I was in the middle of certain people pushing for this and certain people fighting back and does anybody really care? I don’t want the money! I don’t care about the money. I felt like I was a puppet.”

He instead held onto everything the Boston doctor told him and decided to cope with his brain injuries himself. One symptom at a time. If the lights in a room were too bright, he’d change the bulbs. More sleep helped. More exercise. Kolb treated each day like a puzzle, asking himself: “Why am I worse today?” Well, maybe it was the six beers last night. Progress was slow — baby steps — but it was irrefutable progress.

Meanwhile, Kolb continued to reshape his life. He found a church and, six months after that chat with his neighbor, another intimate conversation brought clarity. Searching for more men who lead purposeful lives, Kolb asked his pastor to meet up for lunch. Inside the restaurant, the pastor took one look at this sheepish 6-foot-3, 235-pound man avoiding the long line of people and called him a “recluse.” Kolb didn’t agree at first. A recluse? He just led NFL offenses for a living in front of millions of adoring fans.

The pastor didn’t flinch. He told Kolb he was walking in isolation.

“I was like, ‘Ding! Ding! Ding! Holy smokes. I have totally drawn back from society.’”

This was of course his same problem in the NFL when one concussion bled to the next.

Nobody really had a clue. Granted, Tennesseans and Texans gravitate toward each other in locker rooms. Something about farms and ranches, ex-NFL tight end Lee Smith says. Teammates that summer in 2013, they’ve become exponentially closer the last decade. To the point now, Smith calls Kolb a “a dear, dear person” in his life. Oh, they’ve clashed. Neither individual backs down. There haven’t been many people in Smith’s life telling him things he doesn’t want to hear, and same for Kolb. Their battles create a true bond. They can be honest with each other. Smith had a traumatizing life, too. But while they were able to spend quality time together in Buffalo, it’s not like Kolb was giving Smith a blow-by-blow account of what transpired on Southwestern Boulevard.

“These brain injuries are no joke,” Smith says. “You can’t see ‘em. You don’t know how severe they are. You just have to pray and pray and pray for your friend and be there when you can tell he is struggling. But as men, we don’t tell people those stories in the moment. We just try to grind through it and deal with it on our own. So obviously me and Kevin are close and we had a lot of conversations over dinner tables with our wives. But at the same time, I’m quite certain knowing him — because I would be the same way — that he didn't tell anybody those things were happening. He just tried to grit through it and be a tough guy. Which all of us as males learn as you get older, that’s not the answer.”

His isolation was obviously worse in 2011, in Arizona. Veteran guard Daryn Colledge was a friend and knew this was hard. But he’s right to note that nobody’s exactly chipper through a six-game losing streak. You’re more worried about the teammate who’s gleefully bouncing around the locker room in a good mood than the one who’s depressed.

This is the nature of the profession. It demands a hardened mentality. Ninety-nine percent of players hid their feelings then.

“They’re not vulnerable,” Colledge says. “They’re not there to open themselves up to you. It’s a tough-guy mentality 24/7. A lot of that stuff was stigmatized back when we played. And you’re just now starting to see guys open up and have real conversations about what they’re dealing with on a daily basis.”

Colledge would know. He played through concussions and didn’t even miss a game until his ninth season with the Miami Dolphins in ‘14.

An independent doctor refused to clear Colledge after a concussion. He was livid.

“I was like, ‘Who’s this asshole to tell me I can’t do my job?’” Colledge says. “But he was the guy to protect me. He was the guy to stand between me and the NFL to say, ‘Hey, dude. This isn’t good for you to go out and do it again.’ I’m not saying he saved my life. But who knows what would’ve happened if I would’ve tried to go out and play?”

All along, NFL Life is nothing like Civilian Life. Kolb recently had this conversation with friend, and current Bills backup QB, Case Keenum. NFL life, he told him, is “exaggerated.” The highs are too high. The lows are too low. There’s “deception,” there’s “glory.” It’s not normal. Not with millions of people studying your every move, Truman Show-style. Not when one wrong decision gets you cut the next week. The pressure is intoxicating to one extreme; suffocating to the other.

Transitioning to a life that’s stretched out, that’s more about delayed gratification is not easy.

That’s why Kolb believes so many players hang on as broadcasters, as coaches. Not that there’s anything wrong with that. It’s a primal instinct and, often, lucrative. He’s had offers himself. One major television network asked Kolb to interview for a job. He turned it down. One team extended an opportunity to coach quarterbacks in 2019. He turned this down, too, and it was not easy. All Kolb says is that this was “a very special quarterback in a very special situation.” Briefly, he wondered if his four girls would enjoy the euphoria of a Super Bowl win.

But he’s not looking back.

Kolb’s a busy man today in Granbury, a serial entrepreneur who maneuvers in the business world like Josh Allen outside the pocket.

The majority of Kolb’s time is spent in real estate and development: residential, commercial, industrial, even ranches. At the moment, his group is developing nearly 10,000 acres. He estimates they’ve done about 350 million in revenue the last seven years. He owns a construction company and is busy with an Internet company, “Linxus,” that provides wireless to West Fort Worth. Kolb also runs four autism clinics in the North Texas area. “Thrive” focuses on 1-on-1 therapy with kids ages six to 12. Several parents have told him the program changed their kiddos’ lives.

Kolb heads up the men’s ministry at his pastor’s church.

And, mostly, he enjoys being a Dad to his four daughters: Kamryn (14), Atley (13), Saylor (10), and Parker (six).

He calls them ranch girls who can shoot a gun, bow and arrow and fish better any boys in any locker room. Kolb is positive his girls have made him a better man. They’ve “tenderized” him. When his pal Smith was in town with his family once, Kolb was too harsh on Kamryn — and Smith was blunt. Told him he’d never talk to his daughter that way. Kolb agreed. This was wrong. An hour later, he dropped to one knee and grabbed his daughter’s hand right in front of Smith. “Daddy’s not perfect,” he told his oldest daughter. “I’m going to tell you I’m sorry and do it right in front of this big, burly man so you know that nothing’s going to ever stop me from saying I’m sorry and I love you. And you have to find a man like this when you get older.”

That big, burly man started crying. Smith told Kamryn how lucky she was to have Kolb as a father.

No way does Kolb do this if he had sons to rough up. All of these girls forced him to be the father they need him to be. “And,” he adds, “not the Dad I pictured myself as.”

Word of Kolb’s turnaround got out. This isn’t a world glamorized on ESPN or NFL Network. But exactly like former quarterback Ryan Leaf, he became a force of positivity paying it forward to fellow NFL retirees. His phone’s always open. Kolb gets calls from players at 11:30 p.m. — bawling, begging for help, falling off that “cliff.” It’s common for them to unload all emotions from a locked bedroom, lights off, away from all family members.

“Strong guys,” Kolb says. “Guys you know. And it’s gut-wrenching.”

During these conversations, Kolb explains how their identity is wrapped up in football. And that means adopting traits and habits you cannot even see yourself.

He’d know. He was in their shoes that drive from Guthrie to Granbury in ’14.

“The world is telling you how great it is. The game is telling you how hard it is. The money’s telling you everything is OK. When, really, it’s not,” says Kolb. “So when you get done, the money’s not what you thought it was. And the world is gone — the world’s not telling you anything anymore. Football’s gone. That was your identity. What do you have to fall back on? That’s when a lot of marriages start to struggle. That’s when a lot of kids start to get verbal abuse. And guys like myself start to sink into depression.

“It’s a combination of so many things. People need help.”

Kolb shares words of wisdom to anyone who needs him, all while his own future is a mystery.

He harbors no illusions that he’s in the clear himself.

There’s one symptom he cannot shake. Anyone who’s cracked business deals with Kolb gets used to the former quarterback putting on a pair of sunglasses during meetings. Lights still give him trouble. Once he took the elevator up to the 32nd floor of a building in Houston to pitch an oil-and-gas deal to a private equity group.

He didn’t care that the billionaires looked at him funny. He needed these shades to soothe the pain.

When he gets “scatterbrained” — and his memory flickers — he knows it’s probably a result of those concussions. He tries not to give them too much credit, yet never dismisses them. Brain damage has inherently changed NFL players. Kolb realizes there may be severe consequences. When? Beats him. His plan is to push the worst of the worst ailments down the road by staying active. Many ex-players whose concussions have triggered depression, and even suicidal thoughts like Jamal Lewis, insist it’s imperative to fire those brain neurons.

Lewis is also moving nonstop in business and fatherhood. Colledge is a director of development at Boise State, his alma mater. Smith built a gym in Knoxville, “Triple F Elite Sports Training.” Most NFL players are Type A and obsessive compulsive and addicted to the drug of competition, Smith explains. Punching in-and-out at a typical 9-to-5 job is akin to taking a placebo. He knows serial entrepreneurship has been critical to Kolb’s happiness.

“There’s a reason there’s so many homeless veterans out there,” Smith says. “There’s just nowhere you find a true brotherhood of competition and loyalty and friendship you get in that sport. At the end of the day, he’s a dang good man. Dang good father. Dang good Christian and just wants to better his family’s life and better people's life around him. To say that Kevin Kolb has transitioned out well, especially the way that it all ended, would be an understatement.”

If new science emerges, Kolb is all ears. He’s doing spinal therapy right now and says it’s awakening areas of his body.

It’s true that the NFL has taken steps in the right direction for current players. No longer is the expectation to throw some dirt on that brain and play on. Whether the Arizona Cardinals said so or not, that was life for Kolb in 2011. Thankfully, that’s not life for players in 2023. The NFL still isn’t fully owning concussions as part of the sport. Perhaps you’ve noticed that TV partners now say players are being treated for potential “head injuries.” Rarely concussions. As if a brain jiggling around the skull is akin to a twisted ankle. Too often Roger Goodell and the owners seem to care more about what Mom’s thinking at home than being authentic.

Maybe those at the top still aren’t being completely honest. But players can be.

So, that’s Kolb’s message: Be honest. Be open. Value long-term health over the short-term pressure to play. The worst of his four concussions in four years was the second — the one he concealed — because that’s the one that sent him into a state of isolation. Team and player must be on the same page.

“The isolation and darkness and depression that comes with the confusion of a concussion on the player himself,” Kolb says, “is just as bad as a concussion in my opinion.”

More players may walk away from the sport two or three years early to preserve their bodies and brains, too. Like Colledge.

He chose to retire after nine seasons. He was 33 years old. A man who started 137 of a possible 141 games. Teammates like Kolb are why Colledge left millions of dollars on the table. He didn’t want to risk more brain damage and he didn’t want to endure five knee surgeries like so many ex-linemen. He wanted to be able to play with his kids in his 50s.

“I knew what I was doing was going to shorten my life and that there would be consequences,” Colledge says. “The league wasn’t done with me. I was done with it. Some guys like Kevin luckily grab a bag of cash — but what he had to deal with to get that bag? He’ll have to deal with that for the rest of his life. That saddens me.”

To others, the risk is always worth it.

Every player must follow his own compass.

Kolb is aware of Tua Tagovailoa’s plight. The Dolphins’ rising star suffered two concussions (possibly three?) through the 2022 season alone and was eventually shut down. Once he recovered this offseason, the 25-year-old quarterback took up jiu-jitsu to learn how to fall more gracefully because, much like Kolb taking those knees to the head, Tua’s head trauma struck on plays that were strikingly benign. His helmet bounced off the turf. No infomercial on state-run TV, no rule implemented by suits on Park Avenue fix this. All the league can do is pray Tua stays upright and play the probability game. It’s no coincidence that the Dolphins — a highly entertaining team in a large market — received only three primetime games. Half as many as Buffalo, Dallas, Kansas City and the L.A. Chargers. Even the Jimmy Garoppolo-led Las Vegas Raiders received five.

One can only imagine if Tua has engaged in the same conversations with his wife, if he also believes he’s one strike away. Last season, the two welcomed a son into the world. The good news is head coach Mike McDaniel has publicly maintained that Miami will keep Tagovailoa’s health a top priority — the team was killed for how it initially handled its QB. Everybody’s watching. There will be no Kolb-like isolation. Also, credit the Dolphins for providing Tagovailoa financial security by picking up the fifth-year option on his rookie contract for 2024, a fully guaranteed 23.2 million.

For now, Tagovailoa is as gung-ho as Kolb was exactly one decade ago.

He watched his concussions on film and believes the training is working, noting that tucking in his chin is No. 1. Tagovailoa also shared at his April presser that neurologists told him CTE would not be a problem. They said the disease is more prevalent in players banging their heads against something persistently. Such as linemen, linebackers.

He isn’t looking back, and that’s his right. Free will is what makes this the greatest country on earth.

Kolb will be watching.

“Obviously,” he says. “I am concerned for him.”

The key today is continuing to live this honest life. Kevin Kolb accepts all challenges ahead. Speaking so freely gives him a sense of freedom. He’ll need to deal with symptoms regardless, so why hide? By discussing everything with men at his church, his wife, his kids — all of you reading this — Kolb avoids the isolation and depression that comes with his reality. He’s the opposite of a recluse.

Stories of ex-players battling CTE in their 40s, 50s, 60s are often terrifying. Kolb is 38. It’s impossible to predict what lies ahead. Maybe the prospects are brighter for quarterbacks. It’s true they absorb fewer subconcussive hits over time. Genes could also worsen Kolb’s odds. His mother’s sister died from onset dementia three years ago. He witnessed her health deteriorate “to the point of death” and fears resurfaced.

Is this something my family will be battling with one day?

Are they going to be doing the same thing with me? Do I prepare them for it?

And then Kolb made sure his daughters know the truth about his head trauma. He plotted all worst-case scenarios with his wife.

“They have the freedom, if I’m unsafe, to do this,” says Kolb, ominously. “You don’t have to walk me to the grave. It’s fine. So, again, being open and honest about what could come but also not living in fear.”

Indeed, Kolb soldiers into the great unknown devoid of dread. He feels liberated. The picture he took of his No. 4 Bills jersey in the Redskins’ visiting locker room still hangs on his office wall. The memories of all concussions remain vivid, not suppressed. He’s got no problem supplying all detail from the moments that changed his life. At no point does Kolb actively attempt to steer our conversations toward a more pleasant direction.

The only regret he has is not telling anybody about Concussion No. 2. When it comes to football itself, he has none.

“I would sign up tomorrow for it again.”

But… why?

We’re all struggling to square with our love for the sport when Damar Hamlin receives CPR, Tua’s hand locks up and another round of players are loaded onto a stretcher. The unique violence of the sport has been trumpeted in these pages umpteenth times, from Matthew Judon’s alternate dimension to Wyatt Teller’s pancakes to the Detroit Lions’ gnarly offensive line. Even after all of the injuries he sustained on the field, Kolb embraces the gladiator nature of football. It’s the pressure and the money, he says, that “manipulates” the sport he loves.

Kolb repeats he’d still sign up tomorrow because football gave him tools nothing else in the world can.

“I just didn’t combine them with what God was trying to tell me,” he says, “and I didn’t combine them with good people around me.”

Kolb wishes he could go back in time to put the entire package together. Then, he pauses. He wonders if that’s even conceivable, if it’s even realistic to operate this way because of the mental focus the NFL demands. So, again, he repeats that guys simply need to ask for help. This cuts against the grain of how they’re trained to live in the sport. To play through anything. Especially when a backup is on deck to steal your paycheck. But the more “communication,” the more “circulation of information,” the better. Nobody involved can afford to stick their head in the sand. Owning this darker side will allow future players to more smoothly navigate a path to everlasting happiness.

Kolb is living proof. He believes he’s stimulating the damaged areas of the brain. People keep telling him he’s sharper than ever.

The darkness that came with concussions, on second thought, was always worse than the concussions themselves. Much worse.

Removing this darkness changed his life.

“We need to diagnose what we can handle: the depression, the isolation, the financial issue, the support. The change in lifestyles,” Kolb says. “That’s the stuff where we really need help. Because we’re going to be fighting these injuries — and everybody has some sort of scars and injuries, not just football players — but let’s fight those.”

And that’s the juxtaposition that pissed Leaf off. On draft day, there’s Goodell giving you a bear hug. But when you’re done, he said it becomes, “Don’t let the door hit you on the ass on the way out, kiddo. Good luck.” No player should be subjected to the nonsense Kolb endured with those doctors. Billionaire owners will launch flowery initiatives around whatever The Current Thing is that given month on social media, but when it comes to treating former players with dignity after head trauma? Suddenly, they’re coming up with lint.

Concussions are not a fixable problem. Not unless this transforms into flag, and good luck getting fans to tune into that product.

What is fixable is how the NFL handles its own reality. There are an infinite number of changes owners could make: eliminate the preseason, guarantee more money, shoot “Thursday Night Football” to the sun. Above all? Educate current players and assist former players. Because even though his NFL career was a cataclysmic series of events, Kevin Kolb knows he’s one of the lucky ones.

As he speaks down in Texas, birds chirp and a rooster crows.

Yesterday, Kolb flew to a ministry event. Today, it’s back to business and most of his companies are well-oiled machines by now. He doesn’t need to micromanage, instead doing hands-on work that can change lives. Shortly after this phone call, Kolb will sit down with a gentleman who’s going through a hard time. He’ll pass along many of the life lessons shared here. On Friday, he’ll get quality time in with his girls.

He wants to help anyone he can. Football player or not.

Kevin and Whitney shared a meal with a young couple just last week and, afterward, the young husband across the table told his wife, “See, I told ya!” When Kevin asked what he meant, the kid said he had never met a human being living the life he was put on earth to live quite like Kevin. “You have so much intentionality with everything you do,” he said.

Kevin Kolb can’t lie.

Hearing those words felt pretty damn good.

Dammit, Tyler, this whole thing should be required reading for every person involved in any way with all levels of organized football. It makes me feel guilty for how much emotion I've invest in the game for 60 years or so without a better level of understanding. It started to change a bit for me when Chris Borland abruptly retired. This moves the needle even more.

Thank you for your quality work Tyler. Fascinating man is Kevin Kolb. Didn’t know his story until now. Thanks for always including people’s spiritual lives in your pieces and reporting on the whole person.