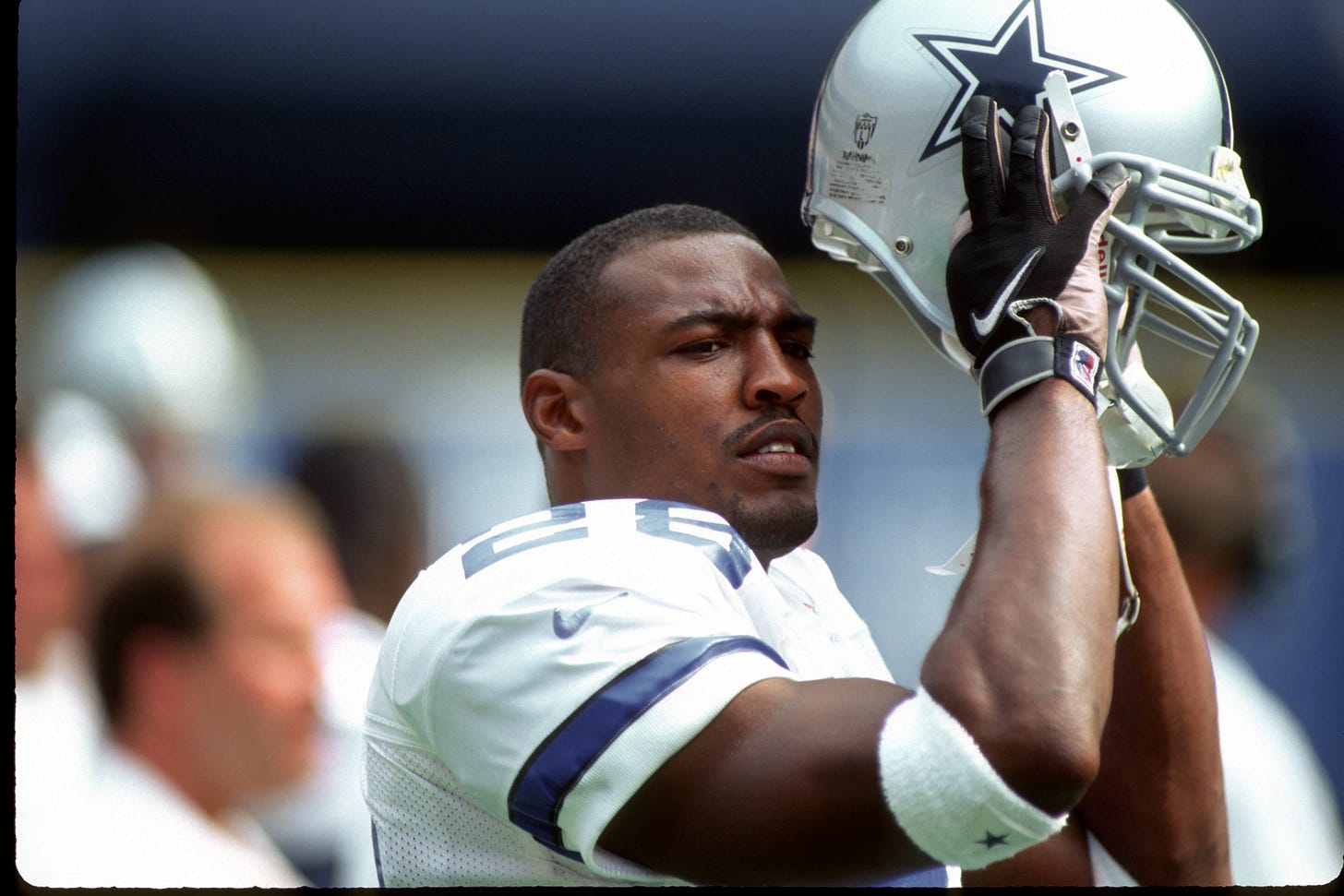

Q&A: Darren Woodson opens up on avoiding gangs, his wild Cowboys days, depression, finding purpose

The all-time great doesn't hold back. Just how crazy were those Cowboys teams in the early 90s? We don't know half of it. Woodson also tells all on how tough it was to adjust to life after football.

What a compelling chat this was with a player we may see in a gold jacket soon. Nobody on that Cowboys 90s dynasty lasted longer than safety Darren Woodson, who finished as the team’s all-time leading tackler.

He’s always been the kind of guy you find any excuse to call, too. An exceptional ESPN analyst, he is now thriving in commercial real estate.

In this week’s Go Long conversation, Woodson is unbelievably open on just how easy it would’ve been for him to join the Crips as a kid (like his best friend), how insane those early days were with the Cowboys (they worked hard and played hard), how difficult it was for him to finally step away from the game and, of course, what he’d do to fix these current Cowboys.

Enjoy.

Your life itself is pretty remarkable. For people who don’t know, fill us in on your roots, your upbringing and what made you who you are.

Woodson: My upbringing was in Phoenix, Arizona. I grew up in a single-parent household. My Mom raised four kids by herself. Worked two jobs. She used to leave one job in particular as a clerk at Maricopa County Superior Court — she was there for 38 years—and she always had a second job. One of her second jobs, she had for 20-some years. And her other one, for the rest. So when I got into the league, I retired her. I got into the league in 1992 and I retired her in ’96. She was the backbone of what I did and who I was. Because, as you can imagine, growing up in the inner-city, I was the youngest of four, I didn’t have a whole lot of guidance. There weren’t a lot of heroes who came back into town or professionals who came back. It was my Mom who was that hero, who worked her ass off. She did all the little things. My mother and my father. They taught me to open doors for women and spanked me when I was bad and kept me away from drugs and the gangs and all. That was my story growing up and I owe her so much. So much. She was definitely my hero.

I lived in the Maryvale area in Phoenix. I got recruited out of college by most schools. I ended up settling with Arizona State and that’s its own story. My grades weren’t good enough. I went to school with a guy names Phillippi Sparks who played with the New York Giants. We came out the same year. Phillippi is popular through his daughter, Jordin Sparks. Who’s a great singer. But Phillippi and I grew up together at the age of three or four years old. Best buddies all those years. Both of us, living on the west side of Phoenix—it wasn’t the school’s fault, it was our fault—but we weren’t focused on grades. So when we got recruited, we were academically ineligible for any D-I school. We got recruited by all these schools and Phillippi ended up going to Glendale Community College. I ended up going to Arizona State and having to sit out for a year and then get back on the field the following year. But it was a tumultuous time, man.

I had no idea, just reading in the Dallas Morning News, that you were good friends with a man named Keith Tucker. He was in an Arizona prison for several years during your playing career and you kept in touch with him?

Woodson: Yeah, man. My best friend growing up was Keith Tucker. Keith and I grew up in the same project and ended up moving to the west side. Every day—if you saw Keith, you saw me, and vice versa. We were thick as thieves. It was about my freshman year in high school when he made the decision — he saw fast money, the drug game and the Crips which was a strong gang in our neighborhood — and he got involved. He got involved heavily because he saw the instant money. He saw guys wearing the nice clothes and driving the nice cars. For me, I had uncles who were in prison who were incarcerated for years. I even told Keith this back then— “Look, I can’t do anything. First of all, my Mom would kick my ass.” Secondly, I knew what it felt like when I would visit my Uncle Sammy in prison at the Florence Prison outside of Phoenix. I remember the sound when they would shut the gates behind us. I didn’t like that sound, man. Crime was not a part of what I wanted to do. You talk about being scared straight. The many times I went and saw him, I just knew that would not be a part of my life. I’m going to go straight and narrow and figure it out. Keith ended up, as the story would unfold, by our senior year we both graduate from high school. And that summer, he has an incident—someone is killed and he becomes a suspect along with a few others—and he ends up going to prison for 26 years. And it was a shame because, first of all, someone lost their life. Secondly, he was doing the wrong thing. Thirdly, being a great friend you want your friends to be around you when you’re growing up and having your success. You always want to be surrounded by your friends. He never had the opportunity to see me play football.

Is he out now?

Woodson: He’s out. He’s been out for the last five years now and lives in Atlanta. He started his life all over again. Married. Works in a distribution center. He does extremely well. He got back on his feet and he’d be the first one to tell you, “I’ll never go back that way again.”

Was it a drug war? Part of the game? What happened?

Woodson: Back then, every corner was part of the economics. If you can sell drugs on a corner — and you owned that corner — you made money. And that’s what it was about. It was about owning a corner on a certain inner-city block and there was a drug war going on, based on that corner, and those are the circumstances that ended up guiding his life. First of all, I was there on the court date he went in, which was one of the saddest days, because I watched his Mom and his Dad, who were good people sit there and watch their son, their baby go to prison. My best friend. But not only that. It was the circumstances, man. This was a good kid, man, from a good family who just made the decision to go the wrong direction. My heart just went out to him and his entire family.

I base everything off of The Wire and that really seems like a scene right out of The Wire. You’re battling for a corner. And that’s just the life? The lifestyle?

Woodson: Yeah! You always know the end game. Nothing good is going to come out of it. At some point, you’re going to get caught. It always seems to end the same way.

I imagine there had to be times you saw this life up close. A lot of guys have come up through tough neighborhoods but, you’re there, so what does it really look like? That line between life and death, how thin is it? Or were you able to avoid it completely?

Woodson: I’m not going to say I was a saint growing up. There were some things I saw with my own eyes. I was in some wrong places. It shouldn’t have been. The results just didn’t end up being the same results. But I can tell you this, my mother, God bless her, did her best to keep us off the street. And she kept us off the street through sports. My two older brothers played football, basketball, baseball. My sister, if the ball rolled, she played it. At the same time, that’s the way she kept us off the street. We were either in church or we were at the YMCA or we were at the park playing. Hanging out on the corner was not going to be a part of what we did, man. And I think that’s the one thing that really saved me in the long run because the guys—the bad guys in the neighborhood, the Crips, the Bloods, the Hispanic gangs in the neighborhood—they knew that. They knew I wasn’t a threat. I wasn’t a guy that was involved in gangs. They knew I was an athlete. And they respected it. My best friend, Keith, would tell me: “You can’t go to this party. Go to practice, get to school, but don’t be riding with me.” And that’s exactly what I did. A lot of those guys took care of me and made sure I was on the path.

And that’s the thing, too. We’re not talking about small gangs here. Bloods, Crips, that’s as big as it gets. But they knew you were on this path of greatness and you could steer clear?

Woodson: Absolutely, absolutely.

Have you stayed in touch with him now since he’s started his new life?

Woodson: Every week. I forgot to mention this, but since he went to prison, every Tuesday I would get a call from the correctional center and I would take his collect call. Every Tuesday. It started when I was in college. It went through when I was in the league. And when I retired from the league. Every Tuesday, I was getting a call at 7 p.m. CST and it was going to be Keith. I took those calls all those years and put funds on his book. I never forgot about it, man. I used to take my kids to go visit him. And the same way I got scared straight, they got scared straight as well by walking through those doors, those gates in that penitentiary. I just talked to him three days ago. I talk to him at least five, six times a month. I got to know his wife and probably talk to her more than I talk to Keith now.

With your playing days, your career, I imagine you’ve got more stories from those Cowboys days than we even have time for. I’ve read “Boys will be Boys” and the stuff you saw up close is wild. When you look back, what are the craziest stories you’ve got from your NFL days with Dallas?

Woodson: I can tell you this, if there was the advent of a phone, back then, half our team would not be playing. I promise you. This is the wildest group I’ve ever been around. And I went to Arizona State which has always been the No. 1 party school and Arizona State had nothing on when I walked in the door and met this group and this personnel on this football team. Jimmy Johnson, as great of a coach as he was, he brought on players who were edgy players. Alpha dog players. They weren’t only edgy and alpha dogs on the football field but a lot of that carried on off the field. So we worked hard and played hard. I can’t mention all the names but you can get a gist for who all of those guys are — the Michael Irvins, the Alvin Harpers, the Nate Newtons, the Charles Haleys of the world.

Man, you talk about a good time? And having a good time? And not only in the locker room but off the field, man, I’ll incriminate myself in his interview. I was right there along with them. Having a great time. Enjoying it. When you’re winning games the way we were winning games in the early 90s and then celebrating those days, Jimmy allowed us to celebrate on Sundays. Allowed us to get it in. But the way he kept us in tact and how he pressed our buttons speaks volumes to who he was because Wednesday, Thursday and Friday, practices were brutal. We hit all the time. We didn’t walk around in shorts and shells. I can’t remember being in shorts and shells when Jimmy Johnson was coaching us. We were in full pads every single day. Even leading up to the Super Bowl, in 1992, we practiced in full pads all the way through. He kept us off the street by trying to keep us fatigued and keep us mentally engaged in what we were doing during the week and keeping it tough. Being tough on the guys.

The reason I give Jimmy so much credit is, now that I’m in corporate America and I’m managing people and have people that are employed through my two companies, I get it. It’s hard to manage people. It’s especially hard to manage alphas who want to do their own thing. Jimmy did a fantastic job of bringing in the right coaches and making the Troy Aikmans leaders and Michael Irvins leaders because he knew if he could get to those guys and make his best players guys who were hard workers, he knew he could lead that group.

Your team definitely epitomized “work hard, play hard” then. You’re killing each other during the week in a way we’ll never see again and then you’re cutting it loose on Sunday after the games. First off, during the week, what are these practices like during the week with all of these alphas?

Woodson: I can tell you, our week started on Sunday. Sunday was the best time. If we had a Sunday game, that was the best time. That was a celebration. That was the time where we could let go. I was so happy I didn’t have to go to practice and hit someone on my own team. I loved to hit guys that I didn’t know and play against other teams. So that was the best part of it, honestly, hands down. Monday was brutal. Monday was the time when all the mistakes — I could’ve had 20 tackles, two interceptions and had a great game — but Monday? If I missed one tackle, it was highlighted. If I loafed to the ball, it was highlighted. The criticism that came along? It wasn’t just the coaches, man. We used to hold ourselves to a higher standard. I’d be in the meeting room after a bad game and the guys next to me would wear me out. Like, “We expect more from you.” Ken Norton was not going to let you forget. James Washington wasn’t going to let you forget. Charles Haley wasn’t going to let you forget those games. Tony Tolbert. Guys held each other accountable for their actions. For me, Mondays were rough. Tuesday was a day off but Tuesday was still a workout day. Jimmy demanded that you come in on Tuesday even though we weren’t supposed to come in on Tuesday. We came in on Tuesday to do rehab, to watch film, and then here we go Wednesday, man, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday were full-pad practices.

Jimmy and Jerry “broke up.” I played with Jimmy in 1992 and 1993 and we were back-to-back champs. And I always get the question: “How many do you think you could’ve won with Jimmy?” I always say, “At the minimum, four.” We ended up winning three altogether but I thought we could’ve won four straight. Possibly five. But here’s the thing: I don’t know, physically, if we would’ve held up. Because there was so much of a demand. There’s no way, if we continued to practice the way we practiced… there would’ve been injuries as we got older because of practice. We were a young football team. But it was that mindset of, go all the way out, go all the way in during the week and be fatigued and be beat down. The longevity of that? Jimmy would’ve had to change his practice scheduling as we aged in the 90s.

Because you’re going that hard, beating the piss out of each other all week? And then partying your asses off on Sunday night. What did that look like after these games?

Woodson: They were fun, man. They were good times. You get these kind of alphas in one room after a game, especially after a win, and we’re all meeting in the same spot. In 1992, it was Humperdinks. Right down the street from the stadium. We’d all go home and meet back up at Humperdinks and the drinks would begin. I don’t remember seeing a tab or a bill. The crowd was thick and the business owner at Humperdinks knew we’d bring the crowd. That was our starting point. We’d have drinks and have food and then, from there, we’d hit the night scene. I’d say 90 percent of us were single men. We’d all just run together. We ran together in the same circles. The Larry Browns and the Kevin Smiths and the guys I ran with were just young dudes, my age, I think our average age was 24. I was 22 coming into the league. That’s how we used to do it. I always tell people, the worst person you can ever have is a young kid with money in his pocket. The worst.

You could also call that being in your prime.

Woodson: Yes, you could call that being in your prime!

You were the longest-tenured member of that dynasty. You lasted the longest. Whether it’s personally or with the team, what memories do you cherish most?

Woodson: The locker room. Winning championships is one thing and I do remember what it felt like afterward. But the relationships. I still have those relationships to this day. I just did a charity event with Charles Haley and helped with his benefit. Russell Maryland. Tony Tolbert is still one of my best friends. Kevin Smith. Larry Brown. Deion Sanders. Emmitt and I are best of buddies — we’re still doing lunch and dinners together as families. One thing about it, when you go through what we went through and you have these relationships, not only are these relationships with the men you spent time with all day and sweat and cried with and the whole nine. You become a part of their families as well. A lot of the guys now, our kids have grown up together. We’ve gotten to know each other, specifically in this Dallas market. I know all of Daryl Johnston’s kids. I’ve known them since they could walk. I know Stephen Jones’ kids. They’re still family, man. They were phenomenal times.

I didn’t know that in 1993 that you broke your forearm and played through it. When you go through stuff like that, a bond will be forged, won’t it?

Woodson: When you win championships and go through the ups and downs of a season, think about this. We’re working together every single day in the offseason. The offseason used to start in March — not in May. It started in March. So you’re with these guys every single day from March on and the ultimate goal is to win a championship. You go through the season and you have injuries, you have guys who get cut, you have guys brought on the team, you have guys who get injured, you get injured yourself, you get banged up. You win games. You lose close games. You’re crying after games—there’s that emotional side of things. You’re going through this and spending more time with them than you are your family. Hell, I’m showing up at 6:30 and I don’t leave the facility until 6 o’clock. It’s an all-day affair. You finally get home and say, “Hey wife, hey son,” and you go to sleep. You forge this unity with guys that never ends. I don’t remember a lot of the plays — if I had an interception or a big hit — but I do remember the jokes that used to take place in the locker room and I still remember those jokes. That’s the most fun part about it. Absolutely.

That camaraderie. Those bonds. I asked Donte Whitner this, too, but when you finally step away from this environment that you’re a part of, how difficult was it for you to create a new identity and a new life?

Woodson: That’s a great question because the transition for me was the hardest thing in moving away from football. In general. Just football. I played the game since I was seven years old. Never missed a season. I missed one season coming into college because I had to sit out for academic problems. But it had been a part of my life, a part of my identity for the longest time. We had so much success in Dallas and you build these bonds. It started from the Jones family. To this day, if Charlotte Jones asks me to do anything in the community, I’m doing it. I know where her heart is. It’s family. They’ll do anything for me and I’ll do anything for them. To step away from the camaraderie in the locker room and the scheduling, think about any professional athlete, we’re programmed to do things: Get up in the morning, go work out, have somebody mold the workout for you, understand what you should be eating and what you should stay away from. There’s so much structure that goes on. It’s almost like the military. There’s so much structure in your life that after 13 years in the NFL, it becomes a part of you. So when you retire, when you walk away, when you don’t have those guys at your side every day — and you’re not getting those jokes early in the morning and you’re not meeting anymore — it’s like starting all over again. And I was 36 years old when I retired. So 29 years of my life, I was playing that game.

It’s the unknown: Where do I go now? What I had, which 98 percent of the guys who come out of the league don’t have, is I had ESPN to fall back on. It wasn’t the same thing as far as the camaraderie and the ultimate goal of winning a championship. But it gave me the feel of stepping into a role and continuing to have a relationship with football. That saved me. But even through that process, I went through some depression. I just felt like I needed to be a part of something and I wasn’t. So the transition was hard for me. And I’ve had so many conversations with guys I’ve played with — guys who retired before me or got let go — and there’s that depression. It’s filled with divorce which I went through. That’s how bad it got for me. I ended up losing that relationship and going through a divorce. Because I couldn’t find myself. I can be real about it, man, because it’s part of the culture of where we come from. Football players. That transition is life-changing.

I’ve listened to the stories of a lot of guys who didn’t have ESPN to fall back on that have gone through depression and had to figure out that “Why?” Why do I wake up in the morning? There’s a lot of guys trying to figure out what that “Why?” is.

With your depression, when were you at your lowest?

Woodson: My 13th season is when I had the back surgery. I had an L4/L5. I had nerve damage to the point where I could walk but it was a struggle. Instead of me playing my 13th season — right before the season started — I had the surgery and thought I would be able to get back on the field and the nerve wouldn’t regenerate. Everybody told me to take the time. It usually takes a year or so to start going and you could play the following year. But for me, I just, never missed a season due to injury. I wasn’t a part of meetings. I wasn’t around the guys. I was going through a rehab process. I was having setbacks. I’d get better and have these major setbacks. I can still remember being out on the field during the rehab process and I was getting better. This was in early October. I felt like, at the end of October, “OK, I’ll be ready to go and play the rest of this season.” I felt like my legs were getting stronger. And then during the rehab process, I had a major setback. The nerve gave out. The leg gave out. And that’s when they put me on IR. And when they put me on IR, I just went into this spiral of depression.

Really? How so? What goes into that spiral?

Woodson: Not being a part of things. Bill Parcells told me, “Look,” — I can still remember the conversation, Parcells knew my energy, he knew how I was built, football was everything to me, that was my joy — “let’s just take a year off.” He said, “You haven’t missed a season in the NFL. It’s time you sat back, relaxed and got yourself together. If you need help, need counseling, we’ve got the resources for that. I know this is painful for you. But next year, you’ll bounce back and be ready.” I was like, “Yeah, yeah, I got it.” I sat there for a while. He hugged me up and said, “It’s going to be alright.” I went home that day, talked to my former wife and sat down and said, “OK. I’ll sit out this year and come back next year.” Man, it took me a week and I said, “I’m done. I’m done.” It just ate me up to sit there and watch the game. I couldn’t even go to the games because I couldn’t stand long enough. I couldn’t even go to the games, man.

Ego plays into this, man. If I could do it again, I’d take my ego out of it. Pride and ego is the reason the depression started. Being a captain on the team and seeing that “C” on your chest for 11 years? For me, it was everything. “I’m the guy. I’m the leader of this defense.” I took on that responsibility of being that guy. When I didn’t play that year, they weren’t coming to me for anything.

It’s your self-identity.

Woodson: Yeah. Guys aren’t coming to me in meetings or asking questions. It was like, “What worth do I have for this organization?” I had already started that downhill spiral and I was outside playing ball with my oldest son, D.J., and we were just throwing the football. And at the time I was still struggling a bit. It was October. I already knew I wasn’t going to play the rest of the season but I was playing catch. Simple pitch and catch. He throws the ball, it goes over my head and I reached up to try to get it and I fell down. So I’m on my knees and my son runs by me to get the football. He knew I was still dealing with that stuff. He gets the football, says “Dad, you OK?” and I’m watching him run and I’m like, “Man, I can’t even play catch with my son. This is bullshit. I can’t do this. This is it. I need to get healthy. All I want to do is be able to play catch with him. Let’s put life into perspective.” I was, “I’m done.”

The luxury I did have was I had an agent, George Bass, who was a mentor. George helped me go through the process with ESPN and was with a real estate firm that I got to know extremely well. They were developers. He kept on saying, “Hey, man, there’s life after football. This isn’t it. This real estate game, I want you to understand it.” He’s the reason I’m doing that now.

You get into TV. You get into real estate. It’s just about finding a purpose, isn’t it?

Woodson: You start finding that “Why?” The luxury I did have, I was programmed. Get up in the morning and go. That was still in me. I didn’t lose that part of me which a lot of athletes lose that part. They stop. They play video games and hang out. That was still a part of me. I’ve been working since I was 12 years old. I was laying carpet with my uncle at 12. My Mom worked two jobs. I knew work was a part of it. Your ass has to grind. I was an early-morning guy. So the group I was with, the development group, was early morning guys. I get my workout in, I’m in the office, I have my coffee, I’m ready to go. That saved me. A routine saved me. From the depression and not knowing what I wanted to do. And part of it, too, is having the ability to understand, “Yeah, you played football.” Which is a game. But life is life. It doesn’t stop at 36. You’ve got to keep going and keep plugging. Your kids are watching you. I knew I had to keep going, keep plugging and knew I wanted more in my life. I haven’t stopped, to this day.

So you know a lot of guys who are struggling through this? Are you reaching out to those former teammates to help them with their own depression?

Woodson: Absolutely. And I’m proud of them, too. I’ll mention one: Kenny Gant. We used to call him “The Shark.” With the Cowboys, he was a special teams demon. Just hearing his story and how he played eight to 10 years and he went through the same thing. He went through the depression in trying to figure out his identity. He worked in a warehouse, didn’t work and, now, he has figured it out he needed that same routine in the work world. Because life doesn’t stop. He’s the same guy. However you measure success — putting the time in, keeping yourself energized — that’s exactly what he’s been doing. There’s a number of guys who really, really rebounded. They’ve gone through depression for a long time and didn’t know it was depression and figured it out after a while and got back on their feet and are getting things done.

You’re still there in Dallas. How in the hell do you fix these Cowboys? What do you see? What’s the problem?

Woodson: We don’t have enough time on this phone. You ask me how to fix the Cowboys? That’s a year and a half conversation with a mixed drink right in front of us. I couldn’t tell you, man. This team, of course you lose your bookend tackles, who I feel are your best players. You lose those two guys and you’ve lost a lot. You lose Dak, of course, who is your franchise quarterback. I wish they would’ve taken care of him and paid him this past offseason. You lose players — and I get it, coaching is big in this league — but personnel is big as well. Players make plays on Sundays. You’ve got to have your mainstay guys healthy on the field. But, listen, everybody’s dealing with injuries. That’s part of the game.

I look at this team and you’ve got to start with personnel and what you have on the field. Years past, I’ve felt like they’ve done a great job of drafting. Up front. The offensive line. The big problem is defensively — getting stops. They can’t get stops. They haven’t been getting stops this entire year. They’re still young in the secondary. Right now, there’s not a lot of playmakers on the backside of that defense. The linebackers are average. And the defensive line has had its struggles. It’s a recipe for disaster for Mike Nolan and that defense. They need to invest defensively. And in years they haven’t. They’ve been investing their resources into the offensive line and the skill positions and Zeke and Amari Cooper and CeeDee Lamb. That’s all great. But in November and December, defense wins games up front.

I’ve written in the past about everything that went down in Green Bay. But some guys who played for Mike McCarthy did not have the best things to say — specifically about that defensive mindset and building a tough team and a tough program. I don’t know how plugged in you are but what kind of job has he done in Dallas?

Woodson: I know Coach McCarthy is welcoming and welcomes back all the former players and whatnot but I don’t have that relationship to understand exactly where they are. I’ve always wanted to know what that relationship in Green Bay was like — all you heard were the stories of Aaron Rodgers and Mike McCarthy going at it all the time. But, hell, I hear that about Aaron Rodgers with everybody. He’s always going at somebody. You just don’t know who to blame and what the situation was. I’ve always been curious to know what his background is and how he personally coached and how he dealt with the players.

When you look back at your career, how do you want people to remember you?

Woodson: As a player, I could play in any generation. I’ve played multiple positions on defense. I played safety, I covered the slot, I never came off the field. So on third downs, I was the nickel guy who covered the slot receiver, covered the tight end, I was versatile in all phases of the game. The all-time leading tackler for the Cowboys but the second all-time leading tackler in special teams. So, to me, it was two phases of the game. Playing defense and being versatile there but also recognizing how important special teams were. One of the biggest compliments I’ve ever gotten was when Parcells came in and the first thing he said was, “I remember dealing with you on the defensive side of the ball playing multiple positions, but also having to deal with your ass on special teams.” If I can affect two phases of the game, I think I’ve done my job.

As a player that’s what I would want people to recognize — the versatility and the ability to play in any generation. Any era.

Also, a man that made the transition and just humbled myself. I needed to humble myself. I was humbled. I understood life goes on. I can make a huge dent in the community. I can be a hero or a mentor to look up to for these young kids in the community. The football career was one thing but what I’m doing in the community right now with C5 Texas and the charity group I’m involved with, that’s the difference. That’s an impact. Playing football was a game but what I’m doing now is impacting young kids’ lives. That’s what I cherish the most.

Now you just need to get into the Hall of Fame. Will that happen this year?

Woodson: Look, man, I wish I had the keys for that. … Yeah, I’m the all-time leading tackler but I have 24 interceptions. I’ve talked to Rick Gosselin and Charean (Williams) here in Dallas (with the Hall) and they think I could have 50 and I’m like, “I would’ve had 50 if Mike Zimmer didn’t have me playing the slot receiver and I could play in the middle of the field.” Let me play in the middle and yeah! But it’s not just that. Looking at the safety playing in the 90s and there’s not one safety where you can sit there and say, “OK…” The LeRoy Butlers, myself, Merton Hanks, there were some really good players who could play multiple positions and transition into today’s game. We just didn’t get recognized. The great thing that happened a couple years ago is Brian Dawkins got in. Hopefully that opens up the floodgates with him getting recognized in the 2000s as one of the top safeties. Hopefully the 2000 safeties open it up for the 90s and 80s safeties. Open up that gateway for us.

It’s all part of life. You hope it happens. I’d love to be in.