Why Lee Smith is the Great American Tight End Story

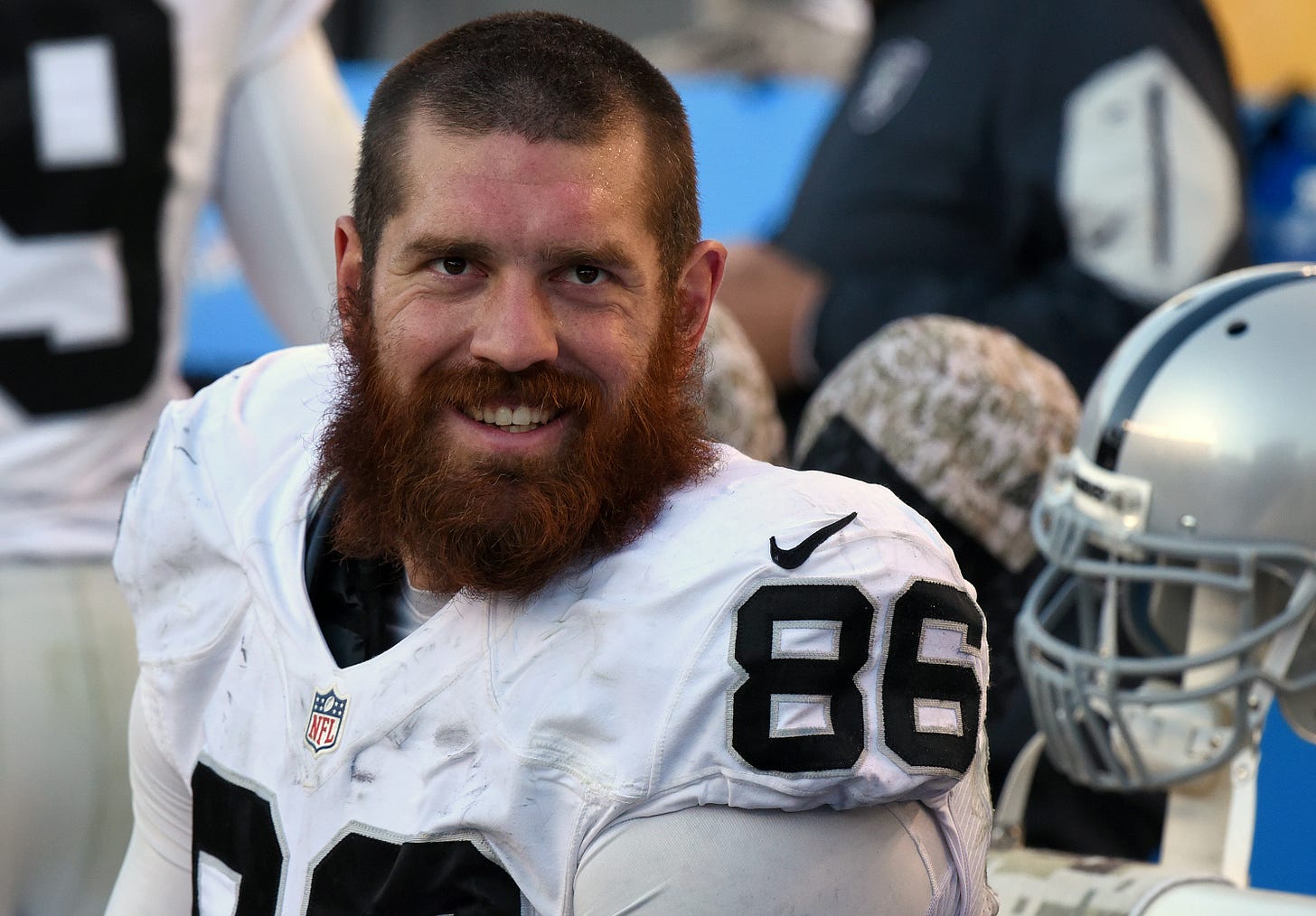

An abusive, alcoholic father sent the tight end to a very dark place. Yet, instead of ending up in a ditch, Lee Smith became one of the best blocking tight ends this century. How?

His face was shattered.

His life was falling apart.

A few months into his second attempt at college football — at Marshall University — Lee Smith was in emergency surgery. Simply put, he got into a fight with an older teammate who punched harder than him. Smith’s throat swelled, his face was broken in multiple places and he was forced to eat from a feeding tube. Unable to speak, Smith communicated with loved ones by jotting thoughts down on index cards. Doctors quite literally needed to put Smith’s face back together.

Granted, Smith wasn’t even pissed at the player (Joe Bragg) who sent him here.

This was what he calls “the old-school way.”

“You go in the locker room. You fight each other. You shake hands. You move on,” Smith says. “It’s a different world now than it was back then. And he just hit me harder than I hit him. I’ve been punched in the face a lot in my life. I finally got hit harder than my face could handle.”

The life of a professional football player can often seem like something from a faraway planet. “Animalistic,” says Smith, noting that Merrill Lynch employees aren’t using fists to settle day-to-day arguments. That is why so many players struggle once they’re ejected back into mainstream society. It’s not because they’re “pieces of shit,” as Smith puts in his blunt Tennessee tone. It’s not because they don’t love their families.

“It’s because they can’t find what they’ve had their entire professional life,” Smith continues, “and then they get thrown into the wolves.”

People can cast blame and judge and criticize… and they’ll never understand.

“To go in the locker room and just bareknuckle beat each other’s jaws in and then shake hands after, that’s just not something most people can get in the headspace of.”

Join our community at Go Long today! Get all profiles, all deep dives, all Q&As, all independent journalism delivered to your inbox by signing up right here:

As Lee Smith laid on that hospital bed, he knew his life needed to change.

Very quickly, he was spiraling.

Smith’s odyssey at the tight end position parallels the lives of so many you’ll read about in “The Blood and Guts: How Tight Ends Save Football,” dropping Oct. 18. (Pre-order today!) Like Mike Ditka, he grew up with a father who wasn’t afraid to put his hands on him. The difference here was that Smith’s father, Daryle, was a former NFL offensive lineman. After retiring, Dad started a construction company. It went under. He lost everything. He fell into an abyss of alcoholism. The man who raised Lee the first 10 years of his life disappeared.

Which made Lee bitter, angry.

Which sent Lee into his own abyss of terrible decisions. He drank through high school and could’ve killed himself. As soon as this Knoxville native got to his dream school — the University of Tennessee — he got a DUI, failed a class because he cheated, never played a down, headed to Marshall and, yes, got his face pounded in. Then, all Lee Smith did was completely turn his life around and last 11 seasons in the NFL. With the Buffalo Bills, Oakland Raiders, Bills again and the Atlanta Falcons, Smith became the preeminent leader of every locker room. Players from all positions, all backgrounds looked up to him. Respected him. Hell, Smith never even finished with 100 receiving yards in a single season but managed to last 150-plus games over a decade-plus because he was such a throwback who relished life in the trenches.

There are many parallels.

Like Ditka, he could’ve drank himself into a ditch somewhere. Like Mark Bruener, he embraced the 12-round fight vs. a defensive end. Like Tony Gonzalez, as a Dad today, he wants his kids to face adversity because it’s good for the soul. Like Dallas Clark, a tight end who experienced his own severe trauma, Smith became interested in psychology and the concept of nature vs. nurture. That nurture side fascinated him most in college. Without the proper role models in place, anyone can go off the rails.

When he couldn’t speak, Smith wrote on an index card to Mom that he planned on marrying his girlfriend. They did, and Alisha saved his life. They've raised four children together and now Smith gives back through his gym in Knoxville: “Triple F,” which stands for “Faith Family Football.” He aims to be a resource for any kids going through hard times.

Here's my conversation with Smith on his rugged upbringing and how he became one of the greatest blocking tight ends of this generation.

And, of course, it’d be incredible if you added “The Blood and Guts” to your library. Secure your copy at Amazon or anywhere books are sold — thank you, all!

This is a position saving football. The blood and the guts of the sport itself. Back to 1967 and 1968, Mike Ditka went through a similar ordeal as you with alcohol. But where does this start for you? The first 10, 11 years of your life everything is good, right? You’ve got a loving family. Then, things take a turn.

Smith: My Dad played in the NFL as well. He was an offensive lineman. So that’s where I get my play style from. He was a gritty f--ker back in the day. When football was pure. Obviously there’s been some great things with the rule changes for our long-term health and all the head stuff. Every time we go to the bargaining agreement, our main goal is to work less and wear pads less. That’s just how the players are wired. So, it’s definitely gotten better from the way those guys used to get killed. But those dudes were also the toughest men who ever walked into this league and built our league for us. My pops wasn’t a stellar player like some of the names you’re naming but he was in the league and his transition out was just brutal. So once that happened, a lot changed in the Smith house.

What did you love about being a gritty f--ker in the middle of the trenches?

Smith: My Dad never had the talent. He was an undrafted player that got in as a scab in the ’87 strike. He got called every name in the book by the stars who were trying to improve the league. I was a union rep for a long time. Sometimes, players unify together and do things to get things done. That’s what they were trying to do in ’87 to get issues handled. I would’ve done the same thing if I was a veteran leader in ’87. But it gave my Dad an opportunity to sneak in and he lasted six years. He was a gritty, hard-working f--ker that had no draft grade. Nobody wanted to touch him out of Tennessee. The only way he had a chance was as a scab player. And then he got a six-year NFL career out of it. The toughness and the grittiness is what I admired. It’s not like he was a 100-game starter. He was the plug-and-play journeyman that was a swing tackle. But all of those dudes back in the day were wired right to say the least.

You were really young. Are you more so talking about watching highlights of his game?

Smith: Just like I have a 13-year-old boy and a 10-year-old boy, I would like to think — this football world’s so small, it’s such a unique brotherhood, a fraternity — hopefully my 13-year-old will definitely remember watching Dad play. My 10-year-old maybe not as much. But when he runs into somebody that I crossed paths with along my football journey, what ex-teammates, management, coaches, anybody has to say about my character and the way I handled myself will give them a good picture of who Dad was. And that was pretty much it with my pops. I don’t have any memory of watching him play in person. I was young. But I never met anyone from my Dad’s playing days that didn’t say, “Man, he was one tough f--ker. Man, he did things the right way. He was always reliable.”

He’s battling Reggie White with the Eagles in practice.

Smith: He was with Reggie in Tennessee and Philadelphia. I remember Reggie’s deep voice very vividly from my childhood. So, I’ve been around this game a whole lot. Those dudes were the real deal. There’s a reason so many of them are dead in their 40s. It’s definitely been a great change to all of our NFL labor stuff but I’m glad I got raised by that generation of men because they were wired right and tough dudes.

That’s the double-edged sword. That play style, who knows what it’ll do to you later in life. But it’ll make you tough. Physically and mentally. What appealed to you about that style of play?

Smith: I love the game of football. I love the X’s and O’s. I love everything about it and want to stay around it to help young men grow in the game of football. But for me, it was an outlet for sure. There’s not many guys in the NFL throughout my journey who’ve come from parents and backgrounds with deep pockets and mansions. It’s our only way out and it’s something that we fall in love with and it becomes our life which is also why — shortly after — so many guys struggle. It becomes who you are. Your ethos. Because it gives you that safe haven away from everything else in your life. It might be toxic. It might be negative. Poor, poverty, all that stuff. Football was a way for me to change the live my four kids now have, compared to what they would’ve had otherwise.

What was it like when your Dad was really into the drinking and back home and lost and… you are taking the brunt of it?

Smith: He was the best man who I’ve ever known when he was right. And when he wasn’t? Looking back, I’m thankful for that side too because it gave me a passion to help these young men, these young kids. And it made me gritty as shit. Let’s just call it what it is. Would I be the big, tough, gritty guy I am for an 11-year NFL career without that? I don’t know. I try to manufacture adversity for my two boys. I don’t walk up and punch them in the back of the head while they’re eating dinner just so they have some type of grit in their life instead of this silver spoon shit they go through every day. But I’m definitely thankful for that side of him just as I am the good side of him because I got to see both sides. Which not many kids get to have the best Dad on the planet — the man who is their hero — but also get to see the toxic, brutal side. I’m thankful for both. It’s been a hell of a ride in the NFL and I give him a lot of credit. Both versions of him. The good version and the bad version for who I am.

Obviously there’s some negativity that came with the bad version. But in a 4-minute drill or on the goal line — when you’ve gotten your ass kicked by an ex-NFL player as a kid — there’s not much worse than that. So when you put your hand in the dirt, you think, “Alright. It’s my turn to whip somebody’s ass.”

Ditka looks back at his beatings from Dad a little more fondly. It wasn’t as alcohol-induced. More of a belt as a form of punishment. How did your Dad hit you?

Smith: He wouldn’t beat me to a bloody pulp and put me in the hospital. But he was an aggressive, mean, mean drunk. So, he definitely laid his hands on me on multiple occasions. Did he punch me in the face and knock my teeth out and leave me laying there bloody? No. But once you get manhandled and you have no ability to protect yourself, there’s no worse feeling in the world. That’s why I tell my kids all the time, I’ll deal with a lot of things. I’ll put up with a lot. I’ll always have your back. But there’s no bigger form of a chicken-shit coward than a bully. If I ever hear you’re bullying anybody, there will be hell to pay when you get home because God doesn’t give you a big body or a big personality or give you leadership abilities to bully people. That all stems from that helpless feeling of not being able to defend myself. No human being should ever feel that. That’s not the way life is supposed to go. Especially not by the people who are supposed to be taking care of you.

Shoving, punching, hitting, all the above?

Smith: Yeah, yeah, yeah. He was more of a snatch you up and pin you against a wall. But I took a few fists for sure. Never in the face. He never hit me in the face. Ever. The body blows were live.

So, it’s not visible in the public?

Smith: It wasn’t some abusive husband out there who just throws body shots all day so the public won’t see. It was just kind of drunken, weak moments where he wasn’t himself. It wasn’t this vicious, abusive, every day getting beaten type of deal. He was a good man. Alcohol turned him into something he wasn’t.

It’s bound to affect you. You’ve said that you are lucky to be alive with where you were age 15 to 19.

Smith: So while I’m thankful for both sides of him — and not to put all the blame on him, I should’ve manned up and made better decisions earlier than I did — I’m thankful for all of it. It made me who I am. Once you get a taste for alcohol or drugs, it hits people differently. It’s not all my Dad’s fault but there was definitely no consequences for my actions in those teenage years. And for a personality like mine — wild and crazy at my core — it wasn’t a good combination to not have consequences.

What were those moments then that were life or death for you? Where things really could have gone south?

Smith: Waking up and not knowing how in the hell I got home. A lot of driving while I was drinking. A lot of hell-raising.

Ditka described his hangover as the same haze, too. He’d wake up and not know how he got there. Taking it to this extreme can be deadly.

Smith: Listen, man. To be an elite player and play a decade — especially the Mike Ditkas of the world — those guys are superstars. I’m just a slappy compared to these guys. To play that long, you don’t do moderation well. Your brain is wired different. When you’re a young man and you don’t have consequences and you don’t have kids and you don’t have people who are relying on you, you can kind of get lost. In that same way we’re so dedicated to our craft as ballplayers, you don’t know how to do the bad stuff in moderation either. That’s when it grabs ahold of you. It’s scary looking back at what potentially could’ve happened.

I’d imagine that moment in the hospital room when you’re eating out of a feeding tube and you have broken bones in your face is the wake-up call?

Smith: That was the final straw of, “OK. I’m never going to make it to the professional level with the way I’m living.” That was the definite wake-up call. I decided to marry my wife shortly after, and she got pregnant shortly after we got married. And don’t get me wrong! I was still an idiot! Hell, I was 19 years old. My wife sure didn’t get to go on cruise control. I give her hell now and tell her she’s on full scholarship. But, shit, she went through a lot of pain and suffering to get there with my ass. I definitely wasn’t perfect even after I got married but that was when I kind of locked in and said, “I’m going to do my best to not make those consistent mistakes I was making that could alter my life and my entire family’s life.”

So, that’s all the dark shit in your past. Let’s talk about the pros. The good times. When did things click? When you realized you could make the tight end position a life for yourself?

Smith: Honestly, there was never a doubt in my mind that I was going to play pro football. Since I was 16 years old. I think that’s what allowed me to be successful with a big, stiff body that can’t run like most of these guys, can’t jump like most of these guys. I was lucky enough to find my little role and obviously a lot of leadership was the cherry on top that came along with that. There was never an a-ha moment. When I got to the University of Tennessee out of high school and saw that those guys were grown-ass men, it was like, “Oh man. I’m not as big and bad as I thought.” But it was never, “Oh man, I can’t be as good as them.” It was just, “Oh shit, I’m a small fish in a big pond. I have to work even harder now. These guys are bigger, stronger, faster than what I even envisioned.” And then I got over to Marshall — after the dark stuff — and then it’s like, “OK, these guys aren’t as bad and bad as those guys over there. But they’re still bigger and badder than me. I need to out-work everyone or I’ll have no chance.” The more I played and even got engrained at Marshall, obviously my awesome wife and young boy there when I was a young player at Marshall saved my life and gave me people who were counting on me. So, I had to dig my boots in the sand even more so.

We had two kids at Marshall. The scouts starting coming around and loving on me. I realized I was a big fish in a small pond again. Especially being in the Conference USA and not in the SEC. You can look around and say, “You know what? I’m pretty dang good at football compared to my competition here. Let me see if I can make this thing a real, real, real reality and then go get paid to play it.”

You’re first drafted by New England in the fifth round of the 2011 draft. Cannot imagine what that tight end room is like, either, with Rob Gronkowski and Aaron Hernandez. You go there. You’re released. You end up in Buffalo. Were you discouraged when you weren’t able to latch on with the team that drafted you?

Smith: I’ve always said that’s the best thing about free agency. You get to cherry pick the team and situation and money and all that good stuff. I was a free agent multiple times and I always loved it. I wanted to know a.) does anybody think I’m great; b.) does anybody think I suck; c) what in the hell are people willing to pay me? I just wanted to know. You hear all these guys bitching and moaning and complaining about being underpaid and not getting opportunities. I’m like, “Hey, man. Free agency is right around the corner. Let’s see what everybody else thinks about you.” I always wanted to know what everybody thought about me. I never thought I was underpaid. I always thought I was fairly paid. I always tried to do my job to the best of my ability regardless of what my salary was.

It’s not like I could sit back and say, “Whoa, whoa, whoa. You have the best two rookie tight ends in the history of pro football. Why in the hell are you drafting me Bill Belichick?” That’s not really an option you get. You get drafted. They had Alge Crumpler up there. I was excited to learn from Alge. He was the veteran in the room. Hell, Aaron and Rob were both younger than me in age. So, I get drafted, Alge retires right before training camp. And I’m the oldest tight end in the room. It was like a twilight zone. I’m like, “What the hell is going on?” And obviously, you go in there with Rob Gronkowski. I’m just glad I had the awareness to realize, “Alright. Not everybody is like this dude. Because I can’t do the shit he can do.” But there’s a reason he’s the best tight end to ever play the game in my opinion — as a complete package. Aaron could do some things movement-wise that there’s no chance in hell I’d be able to do.

I knew they were better than everybody else, too. Not just me. So it wasn’t a discouraging deal. It was a “I’m going to work my ass off and try to be the third tight end on this roster and see what happens.” I was young and dumb then. I didn’t know what to do besides go in and work and play good football. I’m glad I ended up in Buffalo. I didn’t get buried behind a first-ballot Hall of Famer in Rob. Obviously Aaron, you know that story. Which was brutal. Looking back, I don’t know that I would’ve been able to truly show my skillset and build a career and life for my family if I would’ve been buried on that depth chart there. I’m glad they cut me. The waiver wire was good to me. It put me in a place where I could grow and spend six years of my career. Hell, I loved it so much I ended up going back on the back end.

People might not realize you averaged 15 yards per reception one year in college. You were prolific! Making plays down the field. At some point early in your pro career, you realized “I can do this kind of stuff but my livelihood — where I can make bank — is by busting heads, by being an extended tackle and knocking people around.” When did you realize this?

Smith: You get pigeonholed. I ran very poorly at the Combine. I sure wasn’t running a 4.6, no matter how hard I trained or how good of a day I had in Indianapolis. I was a 4.8, 4.9 guy at best. I ran a 5-flat. Once that 5 number gets put on your name, you get pigeonholed as a blocker immediately. Once again, do I run a little better than people realize? Sure, I do. But there’s no way I could do what Travis Kelce and Kellen Winslow and all these guys can do. That just was never going to be my game — getting separation on third down. I’ll never forget: a tight end coach for the 49ers called me up. I wouldn’t be able to pick him out of a lineup. But I know he was the tight end coach for the 49ers in 2011, the year I got drafted. He called me and said, “I just wanted to hit you up. I’m so-and-so, Coach Johnson.” Which was not his name. He said, “We’re not going to draft you. Our tight end room is set. We have other needs. I just wanted to call you and tell you how much I respected your game.” Because I was always just a freakin’ meat head, bash brother, wild man. All the tight end coaches through the draft process loved on me pretty good just because they enjoyed my tape, not because they thought they’d actually draft me. I was just so different than all the other guys.

That tight end coach for the 49ers told me, “Hey, man. Everybody’s going to tell you early in your career ‘The more you can do, the more you can do, the more you can do, the more you can do.’ It’s bullshit. Be the best in the league at one thing and you’ll always have a job.” I never forgot that. I’ve watched it. The more you can do, the less you get paid. It’s just a fact. But that’s what these coaches try to hammer down your throat: “The more you can do. Play special teams! Do this, do that.” Well, Matthew Slater is the best special teams player in the history of the NFL. He’s gone to more Pro Bowls than you have fingers. He’s the best human being on the planet. He’s the best teammate. He’s the best leader. He’s the best blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. Go look up his career earnings. It’s a joke. It’s bullshit. And look up one receiver who has one good year and gets $15 million in one year and fizzles out and two years later he’s out of the league.

Early in my career, I didn’t know how right that man was. But I’m glad he said that to me because I never forgot about it. And the minute I walked into the NFL, I said I don’t care about catching passes. I don’t care about playing special teams. I don’t care about any of that shit. I’m going to do it to the best of my ability — don’t get me wrong. When they throw me a pass, I’m going to catch it. When they ask me to play special teams — I played special teams my whole career. Kickoff, punt, punt block, punt return, I did it all and I did it as best as I possibly could. But my No. 1 priority was to be the best blocking tight end in pro football. Period. That came from that coach in San Francisco and as I got older I really started to realize, “Man. He hit the nail on the head.” They try to convince you that the more you can do, the more you can make. It’s bullshit. Be the best at one thing and you don’t need all the 32 pretty girls at the dance to like you. You just need one and they need to get in their piggy bank a little bit.

That’s such great life advice, too. Anyone can spread themselves thin trying to do too much, and then they’re not great anything. Looks like the coach’s name is Reggie Davis. That ring a bell?

Smith: If you said his name, I wouldn’t know.

Little does he know, he helped you play a decade-plus. Mark Bruener back in the 90s said the same thing on wanting to be a blocking tight end from Day 1 and kicking ass and embracing the stuff that doesn’t make the highlight reel. What was a war story, a battle, a mano-a-mano adversary you had on the field — one you look back and really treasure?

Smith: Early in my career in Buffalo, I really enjoyed playing the Dolphins because they had guys on the edges who were really good. It didn’t matter if you were over there with Olivier Vernon or with Cameron Wake. It was mostly Cameron. And it was a dog fight — twice a year — in my division. And that was the first four years of my career when I was full of piss and vinegar and trying to piss everybody off I played against. And then Tamba Hali was my nemesis. I couldn’t figure out how to block him. So, I just tried to make him mad and fight him all the time. He was my kryptonite for whatever reason. He was a shorter guy but he did all that Kung Fu shit all the time and did all that hand fighting. He was so slippery.

When it’s first or second down and a defensive end knows the run is going the other way, you don’t have to do much to block him. You just have to play pattycake and keep him out of the way. They’re waiting ‘til third down to rush the passer and get paid or they’re wanting to make a tackle for loss on the front side in the run game. Tamba tried to whip your ass every play, no matter where the ball was going, down and distance, nothing. He used to drive me crazy. He’s the only guy who kept me up at night. Von (Miller) is going to make you look stupid three times a game. You’re going to come out of your stance and end up on your forehead. Eating grass. But there’s nothing you can do about that with Von. He’s just better than everybody else. So when you’re making a couple million bucks and Von is making 20-plus, he’s supposed to beat you two or three times a game. That’s the way it works. But he didn’t keep me up at night because I just checked off the fact that I was going to end up on my forehead a few times and just dealt with it. But Tamba was the one who drove me crazy because he was powerful, he was aggressive, he played hard the whole game, he was a bitch to deal with.

When were lines crossed? When did it get really? violent out there?

Smith: They were more talented than me. They were faster than me. They were more explosive than me. By the end of my career, I pretty much knew what the D-Lineman was going to do before he did it. I’d seen everything. I’ve been around. I kind of would be able to win with my brain over my body. Which when I was younger, I just tried to piss everybody off. Because I knew if they were mad at me, they wouldn’t be as concerned with hitting Ryan Fitzpatrick or Fred Jackson or CJ Spiller or Latavius Murray when I was in Oakland. Marshawn. All my buddies. It’d rip my heart out if my guy ever touched them. I couldn’t stand it. So, I just figured if I was as relentless and nasty as I could be, it’d piss off my opponent. As soon as they were mad at me, I was happy. I won. Because now they’re worried about me and kicking my ass as opposed to tackling the guy with the ball in his hand.

Tamba didn’t say much. I don’t know if the guy speaks English to be honest with you. I think I pissed him off one time. He came after me a little bit. Which was awesome. But I was always a guy who might not have heard the whistle. There were plenty of times post-whistle I was rough-housing a little bit. But postgame I always tried to shake those guys’ hands and let them know I respected them. But during the game, they sure weren’t my friends. I had a wife and four kids up in the stands I had to take care of. I wasn’t interested in having buddies during the game.

The way Mike Mularkey put it with Mark Bruener was to play through the “echo” of the whistle and to give one last shove. Were you doing anything else to get under guys’ skin?

Smith: Nah. It was nothing like the Kevin Garnett just absolute shit-talking. That wasn’t my deal. It was that last violent shove. Listen. These are all grown-ass men, and they’re all alpha males. If you get ahold of their jersey and you don’t let go and the whistle’s already blown and they try to walk away and you give them one more tug or you just kind of f--k with them, it just makes them extremely mad. Even if you’re on the backside of a run and the run is 20 yards away from you and you still punch him in the chest or snatch them, all the little stuff, anything I could do to piss them off — without getting a personal foul and hurting my team. I’ve gotten five, 10 personals throughout my career. I tried to get zero. Every once in a while, I went too far. But anything I could do — and it wasn’t with my mouth, it was always with my hands — whatever I could do to just piss him off and make him mad at me was what I was going to do. Period. I didn’t care what it was.

I can remember being in Oakland one week Derek Carr was really under fire and you were the guy who spoke — loudly — on his behalf to try to calm that storm. At some point, you really became the leader of every locker room you were win. Buffalo to Oakland to Buffalo to Atlanta. Did that happen gradually? All of a sudden? What did it mean to become a voice that teammates wanted to follow?

Smith: My No. 1 priority was always my wife and kids. Period. I had a vicious cycle in my family. I wanted to end that cycle and give my family a life to be proud of and a Dad and a husband to be proud of. So that was always my No. 1 priority. But a very close second was my teammates. I didn’t give a shit about catching passes. I didn’t give a shit about a Twitter following. I’m trying to start a business in my post-football career — all my marketing guys are all over me because I was nonexistent in the media my whole career and didn’t use my platform to build a brand and make my name and all that shit that I don’t care about. All I cared about was that my teammates respected me. That started on the field. You cannot lead in the NFL — these guys are animals, most of us didn’t grow up great, most of us didn’t have guidance. Football was our only way out of the shit. When you’re around a lot of men like that, a lot of which had a man who let them down in their life — by a man, I mean their Dad — you have to be genuine, you have to be real, and you have to be a badass on the field. So if you’re not a badass on the field and then you want to stand up and try to lead and say things? They’re looking at you like, “Hey, man, I watched you get your ass whipped on Sunday. Don’t be talking to me.” That’s another reason I played the game the way I did. I wanted my teammates to respect me. I wanted them to know they could count on me.

I was just me, man. A lot of times, coaches, when the season’s not going great or things aren’t going well, coaches’ No. 1 thing, because they’re desperate say, “The leaders need to step up! The leaders need to do this! Where are our leaders at?!” Blah, blah, blah. And it’s like, “Whoa, man.” Now, you’re going to have all these dudes who were not natural-born leaders trying to lead, running their mouth, doing rah-rah speeches and shit. Just be the head coach and let the players lead. The real leaders don’t need a pep talk from the coach. My thing is, I always just try to be genuine. I try to be me and play the game as violently and aggressively as I possibly could so my teammates respected me. And if they followed me, then that was awesome and great and I sure appreciated it. But I never tried to be a leader. I never woke up in the morning and said, “I’m going to lead the DBs today. I’m going to go have a conversation with the linebackers.” Or, “Today, the O-Line needs to be led well.” That was never in my mind. It was: Go to work. Play the game as aggressively and violently as I can. Don’t make mental mistakes. Don’t be getting my friends hit. Just go be as big of a badass as I can be on the field, be genuine and love people and treat everybody the same. That was my deal. I think it was natural and awesome and I thank God for it because it was a God-given gift. It certainly wasn’t something that was manufactured. I was just me, man.

And what about the tight end position allowed that to flourish? To find yourself as a player and a person and play 11 years?

Smith: I’ve always said the tight end position is the most underappreciated and underpaid position on the field. You’ve got Rob Gronkowski, Darren Waller, Travis Kelce, George Kittle, they’re making $15 million per year and you’ve got receivers make $28M. That’s bullshit. That’s an absolute joke. They’re catching just as many balls. They’re catching more balls on third down, which is the money down, the most important down in football to actually win a game. It’s third down. And you’ve got all these tight ends that literally make the game go and they’re making a fraction of what the receiver makes. It’s laughable. And oh, by the way, block Myles Garrett on first down while the receiver just stands out there and sticks his finger up his ass and waits for third down. It’s literally a joke. No. 1, it’s the most underappreciated and underpaid position on the field. Running back is a close second in this new NFL. For whatever reason, they’re not paying the guys anymore.

But I don’t know, man. I didn’t know that I could truly put on the weight to play tackle. And I was always super nervous to try to make that transition and for it to not work and then I’d be out here driving a UPS truck. Not that it would’ve been a bad life. That would’ve been a great life. I’m a country kid. I married a country girl. We would’ve been happy as pigs in shit with her teaching school and me driving a UPS truck. I’m not saying that would’ve been bad. I’m just saying I knew I could play pro football at tight end and I was just always nervous to make that shift to O-Line. So, it was a position that fit my skillset. That’s why I played it. It wasn’t like a “I think tight ends are really cool” or “tight ends are special.” It was, “I’m 6 foot 6, 265 pounds.” I wasn’t explosive enough to come off the edge and deal with the Jonathan Ogdens of the world and actually beat them. So that was it for me.

The position needs more love. I think Kyle Pitts down in Atlanta is the one who’ll finally change the pay scale. He’ll get 20 million per year-plus once he finally gets paid. But, hell, by that point receivers will be making 30 million per year. It’s bullshit. Whatever.

Read all about the 15 tight ends who saved the sport itself from the 1960s to today by pre-ordering “The Blood and Guts” wherever you get your books. They sure teach us quite a bit about the human condition, too.