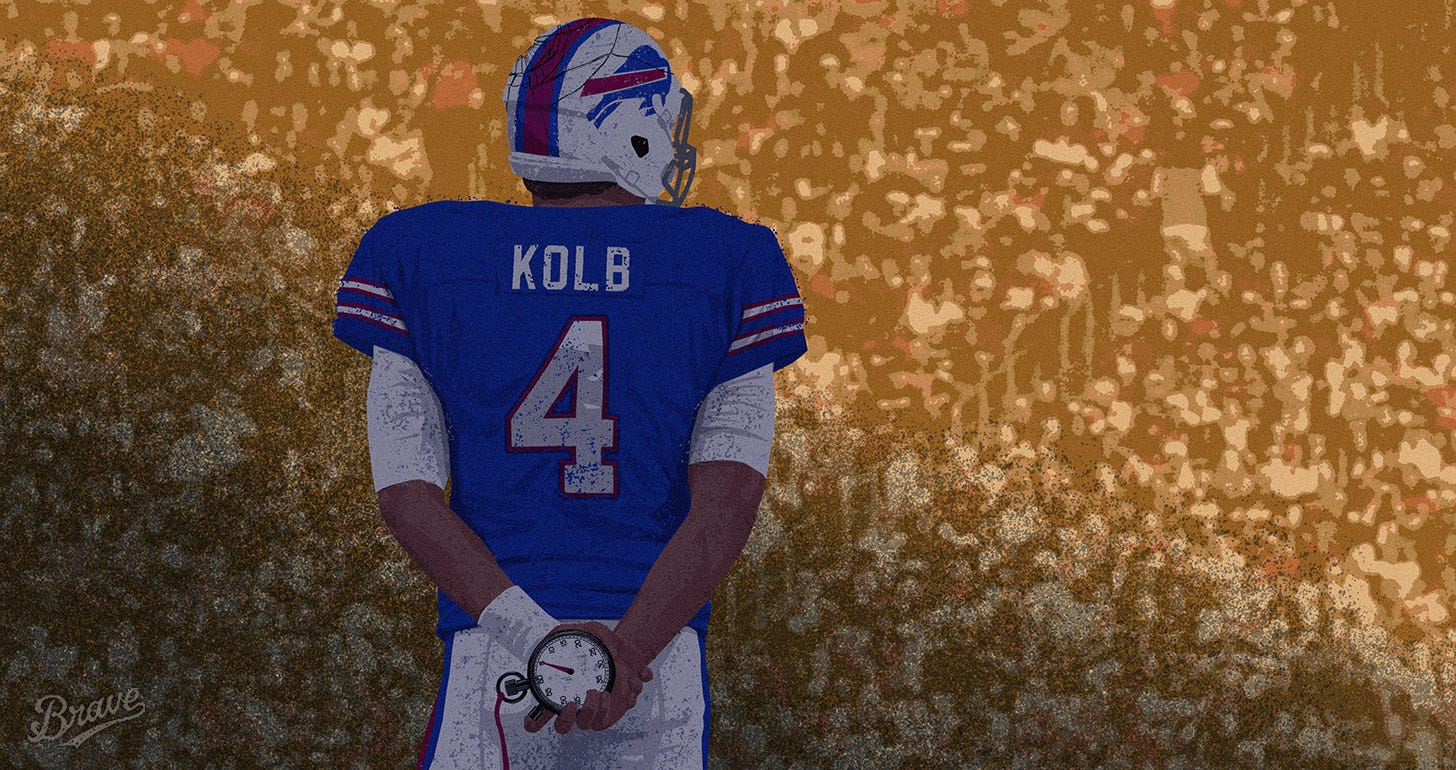

What happened to Kevin Kolb?

Four concussions rocked the quarterback's world more than anyone knew. Kevin Kolb is the story of pro football as much as any star on TV, and he opens up to Go Long about it all.

Part I

He set the internal timer at five minutes. Kevin Kolb knew he had all of five minutes at FedEx Field to decide whether or not his football career was over.

Because into this 2013 season, the Buffalo Bills’ new starting quarterback made up his mind. One more concussion would be four since 2010. His symptoms after No. 3 were so bad, so scary that even a murderous competitor like him knew there was no debate. Concussion No. 4 would swiftly prompt retirement. After absorbing a knee to the head this exhibition game against the Washington Redskins — on Aug. 24, 2013 — Kolb momentarily blacked out, went numb from his neck down and stayed in the game. Even led the Bills to a touchdown that drive.

But he obviously feared the worse. And, this time, his employer genuinely cared. Offensive coordinator Nathaniel Hackett told Kolb that the team’s general manager, Doug Whaley, had called down. He saw the head shot from above in the press box.

“What do you want to do?” Hackett asked.

As the Redskins received the ensuing kickoff, time ticked. Kolb asked for five minutes to be alone with his thoughts. He knew this was bad, but how bad? The rush of adrenaline that masked the pain wore off and Kolb started hyper-analyzing his predicament. Started searching for a fire escape in the maze of a troubled mind: Are you sure you blacked out? Are you sure you went numb? My vision’s blurry and I’m struggling to walk straight but is this really a concussion? Without Kolb, the Bills would have no choice but to rocket-launch E.J. Manuel, a green rookie, into action Week 1. Pressure not lost on Kolb as Hackett paced. And paced.

Finally, the QB calmed himself.

He had played at FedEx several times before. Here, the fans are a mere 15 feet away. When he turned around, the sight was horrifying.

All he saw was a mix of maroon and gold. Kolb couldn’t make out one fan’s face.

His five minutes were up.

Go Long is your independent source for longform journalism. No ads, no corporate masters. We’re powered by our readers and committed to bringing you as close as possible to real pro football.

Two weeks ago, the game we love was celebrated once again. More than 312,000 fans congregated in Kansas City to attend the 2023 NFL Draft, a simple proceeding that the league has turned into its own Woodstock. Only a much more potent psychedelic than LSD is passed around by attendees: Hope. Adults paint their faces, dress up in Halloween costumes and scream at full throat after their beloved team takes an offensive guard from McTucky Tech who they didn’t even know existed two seconds ago. The overrated Beastie Boys blare. YouTubers “Dude Perfect” shamelessly sneak in an NFL Sunday Ticket plug before making a draft pick with Donna Kelce. And, hey, there’s those Bills inviting a “social media influencer” from Canada to make a pick.

What a change from the scene in 2007. Once upon a time, the Philadelphia Eagles selected a quarterback from the University of Houston with the 36th pick and fans on-site ruthlessly booed, flashed thumbs down and stormed away in disgust. Ah, yes. Simpler times. Sadly, that player’s name only washes away in time. Forgotten amid the NFL’s nauseating pageantry. Yet, Kevin Kolb is full proof that pro football is so much more than what the 54 million saw at home watching the NFL Draft and the 113 million saw in Super Bowl LVIII.

More than Roger Goodell bro hugs. More than Patrick Mahomes taking off on one good leg to lead his Kansas City Chiefs to a valiant Super Bowl title in Glendale, Ariz.

This summer marks the 10-year anniversary of this quarterback’s unceremonious exit. And, as much as football’s worth celebrating, there is a dark side. A cost. An underbelly nobody should pretend does not exist.

Concussions did more than damage Kolb’s brain. The hell on earth sent him spiraling into an isolated depression. Perpetually on the cusp of NFL glory — from Donovan McNabb’s handpicked successor to inking a five-year, $63.5 million deal as the face of the Arizona Cardinals to starting for the Buffalo Bills — he, too, envisioned hoisting the Lombardi Trophy. Instead that Glendale stadium was more house of horrors. Each time Kolb was anointed, his brain was battered. Each time his brain was battered, he became less of himself.

Life after Concussion No. 4 was particularly scary.

He nearly killed himself in a head-on collision. And forgot how to drive his daughter to preschool a mile and a half away. And occasionally worried he hit one of his kids backing out of the driveway. Kolb tripped into a bottomless pit of despair.

Such is a world fans have forgotten all about. Somehow, concussions in the NFL shifted from a national crisis that demanded Congress’ attention to the Page F17 cobwebs of our minds. I first chatted with Kolb at the peak of awareness, in 2015, for this piece at The Buffalo News. Kolb was open… to a point. Which was understandable. Personal trauma was still fresh. Since then, concussions took a backseat to other controversies: Kneeling, the Miami Dolphins’ tampering, all things Dan Snyder, Deshaun Watson, the Covid-19 vaccine mandate, etc. Cynical as it sounds, I think the NFL was quite pleased to take on these PR issues rather than one that could genuinely cost owners billions of dollars because these issues, in theory, were fixable.

Push Snyder out. Suspend Watson. Make the unvaxxed wear a mask during press conferences. Strip Miami of a draft pick. Paint a slogan in the end zone and, voila, racism’s solved!

Head trauma, however, is a thorny issue.

As long as football remains a contact sport, the NFL cannot make this problem disappear with one swoop of a magic wand. Owners merely hope you’re not paying attention. That proved difficult last season with one of the game’s premier quarterbacks, Miami’s Tua Tagovailoa, suffering very-public, very-grisly concussions. Sights that prompted another call to Kolb. This time, he relives every hit, every emotion. In Part I, we examine how his NFL career fell apart. In Part II, Kolb details his personal rock bottom and how he got his life back. His odyssey is inspiring retirees across the country.

I love football. You love football. The fact that this profession isn’t for everybody is 100 percent what makes it the greatest sport on the planet. Like anything we love in life, we cannot ignore its flaws.

Kolb’s descent is the story of the sport as much as any quarterback’s ascent. This is how the universe works. For every triumph, there’s tragedy. There’s that kid booed on draft day getting his chance under the same head coach who stood on that Super Bowl podium with Mahomes. So, that’s where this conversation begins: Week 1 of the 2010 NFL season at Lincoln Financial Field. In a sharp Kelly-green uniform, No. 4 took the field as the Philadelphia Eagles’ starting quarterback.

Play-by-play man Joe Buck set the stage.

“I can’t wait to see how Kevin Kolb plays here this afternoon.”

“Everybody’s looking forward to it,” Troy Aikman replied. “He’s waited three years for this opportunity and his hopes are to take advantage of it.”

Eight minutes remain in the first half. It’s 3-3. Third and 14. This is the pressure Kolb’s been dying for as a backup. From his own 18-yard line, lined up in the shotgun, he stares down the barrel of a Green Bay defense that ranked No. 1 last season. “Green 80!” Kolb barks. The Packers only rush three defenders but the pressure of Cullen Jenkins inside flushes Kolb to his left. The quarterback sees something downfield and hesitates to pull up for a throw before re-tucking. Little does he know Clay Matthews is hot on his trail. All the linebacker needs is that fraction of a second to catch, corral and body-slam Kolb. A huge chunk of grass gets lodged in the corner of his facemask. Grimacing in pain, Kolb’s eyes are closed.

Fox’s camera pans to his family up above in a box. His wife clasps her hands, concerned.

Kolb manages to walk off under his power.

He returns for one more series and heads into halftime. His day is done.

Ugly as this appeared, the aftershock of Concussion No. 1 wasn’t that bad.

Kolb recalls brief memory loss. Nothing painful. He also credits the Eagles’ training staff for never putting pressure on him to play. Over the years, he’s been asked to join lawsuits but declined every time because he always felt properly counseled by trainers. After four days, Kolb felt like himself. After 10, he was back to whistling fastballs. There was only one problem: Michael Vick, fresh off 548 days in federal prison, was too good to take off the field. Ahead of this season, head coach Andy Reid asked Kolb for permission to sign Vick. It was fine by him. Now, he was a backup for the fourth straight season.

Kolb briefly got the call when Vick went down with injury, sizzling for 326 yards and three touchdowns vs. Atlanta. But it didn’t matter. This was Vick’s team.

Now, he worried if one hit cost him millions of dollars.

He has no clue why he didn’t throw the damn ball away.

“What am I doing?” Kolb says. “I was trying to make a play, thinking I’d get out of the pocket like it’s college. No, it’s Clay Matthews, boss. You ain’t going to outrun him.”

A lockout gripped the NFL through the offseason — feeding more uncertainty, more anxiety — but, finally, Kolb got his big break. On July 29, 2011, the Eagles traded him to the Cardinals for cornerback Dominique Rodgers-Cromartie and a second-round pick. Kolb’s mega contract included $21 million guaranteed. He headed to the desert determined to play through anything.

The workplace environment was different in 2011. “League of Denial,” the groundbreaking book and documentary that served as a nationwide wake-up call to concussions won’t be released until October 2013. So, forgive the color commentator in this Week 2 tilt between Arizona and Washington for describing Brian Orakpo’s legal, yet vicious hit on Kolb as a “spinal-tap knockout shot.”

The quarterback’s head whiplashes — violently. He stays in the game, a 22-21 loss.

Kolb tells nobody with the team about this second concussion.

In his mind, it’s not an option.

He felt trapped. Completely, utterly trapped. That’s the best way to describe the next six weeks of Kevin Kolb’s life. He repeats the word several times. After Concussion No. 2, Arizona lost six straight games. Kolb wasn’t himself and felt like there was absolutely nothing he could say about it.

The pressure was too suffocating. This team had just made him one of the richest players in the sport — Kolb needed to play. Especially after four years of waiting. He never said a word to the training staff. Loss… after loss… after loss… led to more “heartache,” more “depression.” Kolb faded into an unknown all alone — and he wasn’t exactly sure what was wrong. Was he feeling this way because he was depressed? Sleep-deprived? Emotionally exhausted due to the season caving in? In the moment, Kolb wasn’t sure.

Only later did he realize the concussion from Orakpo’s hit triggered all the above.

“That was a point of solitude and isolation,” Kolb says, “I felt like I was trapped.”

At home, he was a miserable husband and father. Years later, loved ones told Kolb he was “100 percent unapproachable” those two months in 2011. If his wife asked, “Are you OK?” Kolb quickly shot her down. He didn’t want anyone’s sympathy. Instead, he remained isolated and angry. The son of a hard-driving coach, Kolb starred at Stephenville (Texas) High School, then Houston, before patiently biding his time for this opportunity. Everything he had worked for his entire life was now spiraling out of control. The Cardinals were two years removed from a Kurt Warner-led Super Bowl run and he was the man entrusted to keep that window open.

Instead, he played more carelessly than ever before. The symptoms affected his play.

Says Kolb: “I’m just falling off the rails.”

Considering he never pulled himself out after that Orakpo hit — never said a peep — Kolb knew it’d be a terrible look to inform the team out of the blue, “I’m dealing with this from that.” In the old NFL, this is interpreted as an excuse for stinking up the joint. (“They’re going to say, ‘Sure, you say you’re feeling like that. You played like crap,’” Kolb says.) Hence, trapped. This wasn’t a torn ligament or a broken bone that everyone could see. Nor was knowledge of concussions truly mainstream.

Kolb won’t point the finger at Arizona’s trainers because this was still the era of what he calls “suck it up” football. Nobody knew what you were allowed to say when it came to the brain.

By the time 1-5 Arizona traveled to Baltimore, his brain was healed. But his confidence? Shot. Obliterated. As he looked around his penthouse suite in Baltimore that Sunday, Kolb saw at least seven windows and told himself there’s no way he could hit any of them with a football. The last thing he wanted to do was play a football game. The team bus was heading to the stadium in 15 minutes and Kolb had zero clue how he’d take the field to face Ray Lewis, Ed Reed, Terrell Suggs and this nasty defense.

If he was trapped before, now he was begging for mercy.

Right then, Mom’s old advice to pray in times of trouble — “Hit your knees,” she’d say — rang through his mind. Screw it, Kolb told himself, I’m doing it. First came a feeling of embarrassment. Kolb hadn’t prayed in months, hadn’t been to church in forever. The quarterback knelt against the bed and poured his guts out. All anger. All frustration. He was never this vulnerable before in his life. Kolb prayed for God to get him out of this game by any means. He didn’t care if God himself needed to wreck the bus on the way to the Ravens stadium — he was in zero mental condition to play. Overwhelmed in every sense of the word.

He’ll never forget what happened next.

“An angel picked me up. I don’t even know how I stood up off the bed,” Kolb says. “Seriously. And I’m not trying to be over-spiritual. I’m being for real. I turned around and looked behind me, like, ‘What was that?’ It was crazy.”

Newfound confidence — on the spot — coursed through his veins. Kolb felt equipped to face the Ravens, to take on any obstacle. He got on that bus and a long chat with his close friend Joe Flacco during pregame helped even more. Kolb asked the Ravens quarterback how he was dealing with so much public scrutiny — the QB hadn’t won a Super Bowl yet. Flacco told him that he sincerely did not listen to anything. Good, bad, indifferent, he genuinely stopped giving a shit. Kolb, forever a people-pleaser, realized he needed to operate the same way.

The crowd was electric.

Lewis, Baltimore’s belligerent linebacker, exited the tunnel with a divot of grass in his hand and pretended to eat it. Kolb? He remembers being “laser-focused” and, by God, it showed. He began by lacing a 66-yard missile to Larry Fitzgerald on a seam post, one of the most difficult throws for any quarterback. Kolb saw Baltimore sneak its safety into the box pre-snap and smoked one to Fitz, who honestly should’ve scored on the play. The Cardinals were forced to settle for a field goal, but Kolb was excellent. With 3:52 left in the half, he hit Early Doucet on a back-shoulder route for a 10-yard touchdown that gave Arizona a 24-3 lead. “That was an absolute laser shot from Kevin Kolb,” color commentator (and ex-Ravens coach) Brian Billick said on the broadcast. “That thing has to be on the proverbial frozen rope. Kevin Kolb has that kind of arm.”

His magic power had returned.

Kolb went full Henry Rowengartner.

“Like Rookie of the Year with his arm,” says Kolb, referencing the ’93 cult classic. “Boom, Boom, Boom. We’re smoking ‘em.”

Teammates were elated. One by one, they congratulated Kolb on the sideline. Unfortunately, it was all a mirage. That same first half, Kolb also ripped every ligament in his toe. X-ray images showed that nothing was broken, but this was bad. So bad Kolb couldn’t push off his foot. Hell, he could barely execute a handoff to the running back. In his opinion, backup John Skelton would’ve been the team’s best option in the second half. Yet while the team doctor advised he sit out, Kolb says head coach Ken Whisenhunt instructed him to play. Whisenhunt saw Kolb light it up and knew this was a must-win game.

Kolb did not protest and taped the foot up.

Arizona lost, 30-27.

He’ll never forget the look of terror on the faces of the team’s training staff when they removed his cleat afterward. The swelling. The bruising. Sixty percent of his foot was black and blue. Kolb could’ve been confused for an extra in a 90s slasher film.

“They were scared to death,” Kolb says. “They thought they ruined my career, ruined my foot. I remember seeing the look on their face, like, Oh, we screwed this one up.

“You have this ‘I told you so’ feeling. Now what? I fought harder. I hurt my foot worse. And we lost. Why didn’t we just talk about it as men and figure out what the best solution was at halftime?”

Right when Kolb was turning a corner, he was forced to sit four weeks. He clutched dearly to that confidence reboot, that Rowengartner rush of euphoria. I got it! I got it! he repeated to stay in good spirits. The Cardinals’ defense started played better through the 2-2 stretch and it hit Kolb: Temper his gunslingin’ nature and his best days were in front of him. When Kolb returned, he led the Cardinals to a thrilling overtime win over the 7-4 Cowboys.

This was the breakthrough he dreamt of for four years.

An unblocked Anthony Spencer in his face, Kolb deftly floated backward to avoid the sack and sling a quick pass to LaRod Stephens-Howling, who weaved 52 yards to the house.

He wasn’t depressed anymore, no.

As teammates piled on top of each other in the end zone, Kolb ran downfield in jubilation.

The very next week, Arizona hosts the San Francisco 49ers. On his second snap of the game, Kolb is slammed into the turf but does a marvelous job of breaking the fall with his left forearm. He’s OK. The next play, on third and 6, he isn’t so lucky. While being sacked by Justin Smith, he fumbles. Linebacker Ahmad Brooks hustles to the loose ball and inadvertently strikes Kolb in the side of the helmet with his knee.

Kolb slingshots forward. Violently.

He cannot hide this concussion.

The lack of support from teammates and coaches hurt. Their response to this injury was cold.

At least the medical staff knew the truth.

“They knew I wasn’t a liar,” Kolb says. “They knew what I had been through with my foot.”

Either way, none of it mattered. Kolb realized how bad this looked. A player getting paid the big bucks was out… again. There was no way he could play through this concussion because, while everyone else thought this was Concussion No. 2, it was actually No. 3. The symptoms were worse than anyone could’ve guessed. His season was over. Stricken with guilt, with a burning desire to show teammates he cared, Kolb nonetheless traveled with his team to Cincinnati. He didn’t want anyone to think he “abandoned” them — Kolb suspected many players already felt this way. So instead of staying home in a dark room, the quarterback joined them on the sidelines.

A colossal mistake.

Everything was “too bright” and “too loud.” Sunglasses and earplugs only accomplished so much. Google the longest list of concussion symptoms you can find and Kolb estimates he was dealing with 80 percent of them that sunny day. Nauseous. Dizzy. His ears were ringing. He toggled in and out of the locker room to collect himself.

“My head,” Kolb says, “was going to explode. This was the first time I thought my brain was swollen. This is scary. I’m scared to death about what I’m going through.”

Skeleton started those final three games and the Arizona Cardinals’ 2011 season mercifully concluded.

Kolb doesn’t necessarily blame teammates for questioning him this season. On the outside, he appeared fine.

“I’m supposed to come in and be the next Kurt Warner,” Kolb says. “And they’re like, ‘Is this guy tough? Is he not tough? He didn’t play well, then he played well, then he got hurt. He’s got this concussion. He’s talking about having two concussions.’ They didn’t trust me and I don’t blame ‘em. They just didn’t know who I was. And they’re reeling. They’re saying, ‘We suck. We’re losing. We’re fighting for our jobs. We need you out there.’ So, you’re backed into a corner by everybody and it’s nobody’s fault. It’s just the circumstances of how the NFL was at that point and the recognition of what these players go through when they’re dealing with the mental side of things.

“They were losing their trust in me. The trust in me being the quarterback of the future. And I can’t blame them for some of those things. I also couldn’t fully communicate what I was going through. No. 1, they didn’t want to listen. No. 2, sometimes as a football player, you’ve just got to shut up and go for it. I did it one time. I wish I wouldn’t have.”

In all, it took Kolb 10 weeks to recover from this third concussion. At the eight-week mark — in the middle of the night — he sauntered into his bathroom and couldn’t stand upright. Kolb stumbled. Banged into the walls. Decided right then with his wife that he’d quit the sport for good if he suffered one more concussion. When players reconvened in Arizona, Kolb told the organization exactly that. He was treating his brain like a punching bag before even turning 30. His days of hiding anything were over.

The Cardinals staged an open competition between Kolb and Skelton in training camp, Skelton won, Skelton suffered an ankle sprain in Week 1 and Kolb picked up exactly where he left off. Back to that first half in Baltimore. Back to that OT win vs. Dallas. He never forgot that winning formula in his head. Be smart with the ball and Kolb could still achieve greatness. Arizona slayed an ascending Seahawks team that’d win the Super Bowl the next year. Then, the defending AFC Champions in Tom Brady’s New England Patriots. Then, Philly. Then, Miami.

Arizona was 4-0.

Yet, again, it was all a torturous hallucination.

On a game-tying drive against the Buffalo Bills two weeks later, with 2 minutes to go, Kolb whipped the typically tepid Cards fan base into a frenzy with a dashing 22-yard run. He hurried his offense to the line and — on a broken play — turned upfield to salvage what he could before making a wise decision. He immediately collapsed into the fetal position to protect his head. Nonetheless, 6-foot-5, 284-pound defensive end Alex Carrington had time to legally flatten the QB.

Kolb broke his sternum. His season was over.

Two years into that mega contract, Kolb was released by Arizona.

The good news? The Bills never forgot Kolb’s fight that night.

Team president Russ Brandon, along with GM Buddy Nix, head coach Doug Marrone and offensive coordinator Nathaniel Hackett all met with Kolb in Texas over dinner that 2013 offseason. When they asked about his concussions, the quarterback was honest. He explained how the symptoms became progressively worse one… to two…to three, admitting that a fourth would effectively end of his career. Kolb also made it clear that he played a ton of “rough football” those six games in 2012 and emerged without any head trauma. Between the 4-0 start and the Buffalo game, the St. Louis Rams sacked him nine times. His helmet popped off twice. He was OK.

Kolb remained confident. “I got my mojo back,” he remembers saying. “I’m ready to come play ball.”

The Bills were honest, too. They told Kolb their plan was to draft a quarterback high in that 2013 draft and for Kolb to serve as a bridge starter.

Kolb signed April 8 and Nix drafted Florida State’s Manuel 16th overall on April 25 before abruptly retiring — a shock to everyone. His replacement, Whaley, planned to start Kolb in 2013 and bring Manuel along slowly. On Aug. 3, at St. John Fisher College, those plans nearly blew to smithereens. Hustling between drills, Kolb slipped on a slippery rubber mat that was covering concrete. After his knee twisted at an awkward angle, Kolb feared the worst. This is how ACLs tear. He threw his helmet in frustration. He’s still sickened by this injury. (“I was mad. I was mad at myself. I was just mad.”) Looking back, Kolb wonders aloud if this was God telling him to stop playing football.

The next day, he received a phone call in the dorm. His grandmother died — a brutal loss. They were extremely close.

Thankfully, Kolb dodged serious injury. After missing eight days of camp, he was back. He suffered some damage to his knee cap, wore a brace and practiced with a noticeable limp — all minor details. His spirits were lifted once more. As August dragged on, the Bills made it clear this was his team. More than revitalizing his own career, Kolb was jacked to win for Hackett. The up-tempo offense — and Hackett’s infectious exuberance — rejuvenated him beyond his wildest imagination. This felt like backyard football, like the run and shoot back in college. Buffalo’s third exhibition game against Washington would serve as the perfect tune-up. Proof. Nobody was quite sure yet if this fast-paced scheme would translate from the whiteboard to the field. An urgency to ram-rod Hackett’s X’s and O’s to perfection fueled Kolb.

This was more than an ordinary preseason game.

He knifed an 11-yarder to Robert Woods. He took a naked boot four yards.

“You could feel a momentum behind us of, ‘Hey, we’re clicking. This may work.’”

Kolb stepped up to the line on third and 5 from the Redskins 37.

Flushed out of the pocket, he saw an opening.

He hit the gas.

There’s nothing nefarious about this eight-yard gain. No chilling collision, no stretcher. But after Kolb innocently falls forward — coast clear, play over, wisely taking cover again — one Redskin cannot stop. It’s linebacker Brandon Jenkins. A man who’d register all of two career tackles in his NFL career. Jenkins glides downfield in pursuit of Kolb and dings him in the head with his knee.

Nineteen seconds of real time is all that passes before the next play. But in those 19 seconds, Kolb first blacks out. On his feet, his body then goes numb. When running back Fred Jackson grabs him, he’s still tingling. An official approaches Kolb and he pushes him away. Mainly because the next play call’s being relayed by Hackett into his headset. Kolb hustles back to line of scrimmage and completes a short completion to Woods.

One chinstrap is still unbuckled. He doesn’t bother snapping it back in.

The Bills finish this uplifting drive with a C.J. Spiller touchdown run.

Kolb returns to the sideline.

Time begins to tick.

Kevin Kolb turned toward the Redskins’ fans — was greeted with that blur of colors — and freaked.

He told himself, right then, he was finished.

When those five minutes elapsed, and Hackett reappeared for a verdict, no words needed to be said. Kolb finally had a coach who listened, who cared. All he needed to do was shake his head and Hackett went pale. He was crushed. The coordinator took a deep breath and told the other coaches on the headset to buckle up. Everyone’s worst fears were here.

Off Kolb went to the locker room one final time. The quarterback laid his blue No. 4 jersey on the floor, snapped a photo and sent it to his wife with the words: “We’re going home.” He knew this was a possibility all along, but that didn’t make saying goodbye to football any easier. Football defined him as long as he can remember.

Chatting over the phone, Kolb chokes up.

“I’m sad right now thinking about it.”

Teammates and coaches wouldn’t be herding into the locker room for another hour, so Kolb had the room all to himself. To this day, he’s grateful that the Bills training staff left him alone. He needed complete solitude. After his wife responded, Kolb tucked his cell phone away, stared at that jersey, and sobbed.

The hardest part? He loved Buffalo. He loved the team. Kolb felt like he was letting everybody down.

He was still in his pads. His mind raced:

Are you sure this is it? You just told your wife you’re going home. Are you sure you don’t want to go out on top? No, no. I’ve been through that resurrection thing in Arizona and got hurt again. I don’t need that. I’m past that. I proved himself. I’m fine.

A trainer eventually poked his head in to inform Kolb that his teammates were coming. They needed to bring him into a separate room.

He was done. He wouldn’t need to prepare for an NFL defense ever again. Instead, the symptoms of Concussion No. 4 now lurked. Life-threatening symptoms that’d linger for eight months.

Before anything in life could get better, it needed to get worse. Much worse.

The crazy thing? Concussions weren’t even his worst problem.

Part II

Start in the morning with how we all get going.

A cup of coffee.

After Concussion No. 4 ended his pro football career, Kevin Kolb stayed in Western New York for testing and to help rookie E.J. Manuel any way he could. He’d pick up a coffee and — if he consumed too much caffeine? — the retiring quarterback would spiral the second he came down from the high. Caffeine, he says, “exaggerated everything.” He’d feel spacey. Drifted. Start chugging water to offset the caffeine in his system. Even slip a dip of tobacco into his lower lip because research told him nicotine stimulates the brain. Very quickly, Kolb learned this was a rough combination.

“It was bizarre,” Kolb says, “trying to coordinate all of that all the time.”

His memory flickered. Once at the wheel, he needed to ask his daughter how to drive to her preschool.

His sleep suffered. In bed, he’d stare at the ceiling for four hours straight.

His vision blurred. When he read more than three pages of the Bible, words blended together. When he brushed his teeth in front of the mirror, a cloud would form around his face like those Washington Redskins fans in the stands. He’d be jacked up for a solid three hours, too. The sensation was disturbing.

“Like you are walking through the world,” Kolb says, “but you don’t feel part of the world. You feel like you’re just watching everybody. Almost like you’re high. But it’s scary. You’re scared. You don’t even know what’s going on, but you’re walking through life normal. Everybody thinks you’re normal but you’re in a different zone. You’re in a different area. And then whenever it comes back or you get locked in or somebody clicks your focus back in, you’re like, ‘Oh! What just happened the last two hours?’ Or, ‘What just happened at that last stop sign.’ Or, ‘I just forgot where my kids go to school.’ And then fear sets in: Do I tell anybody? What am I supposed to do?”

He wanted to babysit his daughters, to give Mom a break, but this hazy realm of existence became a danger. He could space out for a brief 2 minutes.

The moment Kolb came to, he panicked.

“Like, ‘Oh my gosh, Did I just run my child over when I pulled out of the driveway? Did she just go down to the lake when I wasn’t paying attention?’ When you have those drift-in-and-out moments, my kids were where my real fear was. Because they were all at the age of one to two to eight at that time.”

There were thankfully no such close calls.

Kolb did, however, nearly kill himself.

This memory’s been buried in his mind for 7 1/2 years. Kolb admits he hasn’t even thought about this close call since we last talked. But upon hearing Southwestern Boulevard, the images rush back to him. Yes, Kolb was driving from his home in Lake View to the Bills facility in Orchard Park. After spacing out — “dazed” and “drifted” — he glided over the center line at around 55 miles an hour with an oncoming vehicle only 45 yards away. Back in ’15, he said the other driver reacted. Today, Kolb thinks he corrected over himself.

All Kolb remembers are the six words that immediately crossed his mind upon surviving: What in the hell just happened?

Life without football was off to the worst imaginable start.

Concussion No. 4 predictably torpedoed the 2013 Buffalo Bills. Through a 6-10 season, Manuel struggled. Starting so soon stunted the rookie’s career beyond repair, re-routing the franchise’s search for a franchise quarterback yet again. Manuel never recovered. (Take it from him.) Yet the concussion also torpedoed Kolb’s life in ways he never expected. He visited every possible expert. The first to truly listen was more of a “crazy witch doctor” in Boston, Mass., who advised Kolb live his best possible life: eat right, sleep well, stay disciplined.

Wise words considering these symptoms lasted eight excruciating months.

“I’d fly to the top,” he says, “and then I would fall to the bottom.”

Kolb stayed in Buffalo until Halloween. The next day, his family flew south to their ranch in Guthrie, Texas to reset. They planned on locking down in serene seclusion for an extremely long period of time. After all, Guthrie is the headquarters of the famous “Four Sixes” Ranch. Three months in, Kolb told his wife, Whitney, he was ready to return to their home in Granbury about 3 ½ hours away. Whitney could tell Kevin was wrestling with something but he wouldn’t say. Not yet.

As Kolb took his family back to their lakehouse this rainy day in January 2014, around 2 in the afternoon, he couldn’t hold back his emotions any longer. The finality of his football career was clobbering him with more force than any blitzing linebacker. Now, it was real: Kolb would never throw a pass in the NFL again. His spirit was “ripping.”

His wife was asleep. His daughters were asleep.

Whitney woke up to the sound of her husband’s tears.

“What’s going on with you?” she asked.

“That’s what I lived my whole life for right there,” Kevin answered. “That was it.”

He was only 29 years old. With millions of dollars in the bank. With a beautiful home waiting for him at the end of this drive. With these three beautiful daughters in the backseat and a fourth in the future. But football was forever this man’s reason to wake up in the morning. Strip it away so abruptly and — as Kolb says — it doesn’t matter if you’re prepared or not: “You fall off a cliff.” Many of the sport’s virtues helped, immensely, but Kolb quickly learned that football alone didn’t prepare him for day-to-day life.

The football gods essentially tore off his skin and ejected him into a whole new world.

No concussion symptom felt as bad as this feeling of being deceived.

“I was completely unsettled,” says Kolb. “Everything I had been through for 10 years was condensed down to that one moment. That was the turning point — ‘Are you going to fight it? And live your life in a miserable fashion? Or are you going to repent?’ To say, ‘I’m here Lord. I’m yours. I’m not going to do it my way anymore. You let me run to the end of my leash.’ In my case, the leash was wealth and I got it all. I had it all. And it proved to not be enough.”

That drive, Kolb wiped away his tears and admitted he needed to change.

“Are you going to come with me?” he asked his wife.

“You know I am.”

The next morning, he started a new life.

At 5:30 a.m., Kevin Kolb knocked on a neighbor’s door at Granbury Lake. This was the one man he knew lived with integrity, purpose. The neighbor greeted him in a robe and Kolb cut to the chase: “Just show me how to live.”

While it might’ve felt like he had a million friends as an NFL quarterback, he really didn’t. Kolb admitted he was lonely. He had nobody he could “come clean” with, nor any clue how to walk out a life of character, of living for a higher power. This two-hour conversation was a religious awakening. Step by step, the man showed Kolb how he reads the Bible, and prays with his wife, and the best way Kolb can explain it? He needed to peel back the onion of how he was trained to live as a coach’s son, as a quarterback the last 20 years.

Kolb’s mind began to calm.

His brain, of course, still required assistance.

Not that this was high on the NFL’s priority list.

He didn’t need the money but — considering football was responsible for his brain damage — Kolb sought permanent disability in 2014. It didn’t go well. As former Packers quarterback Don Majkowski detailed to Go Long, these trips to NFL-appointed doctors often morph into “deny and deny until you die.” Other retirees warned Kolb: Say this to that doctor, they’d explain, and you’re screwed. So many are experts in doing the NFL’s bidding. Visit to visit, it felt like nobody was taking Kolb’s health seriously. They’d check his knees… his arms… his chest… before Kolb would cut in. “Hey, it’s my brain, guys!” At which point, one doctor asked if Kolb traveled by airplane. He said he did and the doctor deduced that this must mean he’s A-OK, which Kolb found puzzling since somebody else booked his ticket. Not to mention, those flights sent his brain into a weeklong “whirlwind.”

Whatever. He traveled by car to his next visit, in Houston, a 550-mile roundtrip. This doctor said that if he was able to drive for eight-plus hours, well, he must be fine.

With that, Kolb waved the white flag. He didn’t know what game the NFL was playing but they sure as hell weren’t going to do it with his brain.

Chasing a check wasn’t worth the hassle.

Adds Kolb: “I felt like I was in the middle of certain people pushing for this and certain people fighting back and does anybody really care? I don’t want the money! I don’t care about the money. I felt like I was a puppet.”

He instead held onto everything the Boston doctor told him and decided to cope with his brain injuries himself. One symptom at a time. If the lights in a room were too bright, he’d change the bulbs. More sleep helped. More exercise. Kolb treated each day like a puzzle, asking himself: “Why am I worse today?” Well, maybe it was the six beers last night. Progress was slow — baby steps — but it was irrefutable progress.

Meanwhile, Kolb continued to reshape his life. He found a church and, six months after that chat with his neighbor, another intimate conversation brought clarity. Searching for more men who lead purposeful lives, Kolb asked his pastor to meet up for lunch. Inside the restaurant, the pastor took one look at this sheepish 6-foot-3, 235-pound man avoiding the long line of people and called him a “recluse.” Kolb didn’t agree at first. A recluse? He just led NFL offenses for a living in front of millions of adoring fans.

The pastor didn’t flinch. He told Kolb he was walking in isolation.

“I was like, ‘Ding! Ding! Ding! Holy smokes. I have totally drawn back from society.’”

This was of course his same problem in the NFL when one concussion bled to the next.

Nobody really had a clue. Granted, Tennesseans and Texans gravitate toward each other in locker rooms. Something about farms and ranches, ex-NFL tight end Lee Smith says. Teammates that summer in 2013, they’ve become exponentially closer the last decade. To the point now, Smith calls Kolb a “a dear, dear person” in his life. Oh, they’ve clashed. Neither individual backs down. There haven’t been many people in Smith’s life telling him things he doesn’t want to hear, and same for Kolb. Their battles create a true bond. They can be honest with each other. Smith had a traumatizing life, too. But while they were able to spend quality time together in Buffalo, it’s not like Kolb was giving Smith a blow-by-blow account of what transpired on Southwestern Boulevard.

“These brain injuries are no joke,” Smith says. “You can’t see ‘em. You don’t know how severe they are. You just have to pray and pray and pray for your friend and be there when you can tell he is struggling. But as men, we don’t tell people those stories in the moment. We just try to grind through it and deal with it on our own. So obviously me and Kevin are close and we had a lot of conversations over dinner tables with our wives. But at the same time, I’m quite certain knowing him — because I would be the same way — that he didn't tell anybody those things were happening. He just tried to grit through it and be a tough guy. Which all of us as males learn as you get older, that’s not the answer.”

His isolation was obviously worse in 2011, in Arizona. Veteran guard Daryn Colledge was a friend and knew this was hard. But he’s right to note that nobody’s exactly chipper through a six-game losing streak. You’re more worried about the teammate who’s gleefully bouncing around the locker room in a good mood than the one who’s depressed.

This is the nature of the profession. It demands a hardened mentality. Ninety-nine percent of players hid their feelings then.

“They’re not vulnerable,” Colledge says. “They’re not there to open themselves up to you. It’s a tough-guy mentality 24/7. A lot of that stuff was stigmatized back when we played. And you’re just now starting to see guys open up and have real conversations about what they’re dealing with on a daily basis.”

Colledge would know. He played through concussions and didn’t even miss a game until his ninth season with the Miami Dolphins in ‘14.

An independent doctor refused to clear Colledge after a concussion. He was livid.

“I was like, ‘Who’s this asshole to tell me I can’t do my job?’” Colledge says. “But he was the guy to protect me. He was the guy to stand between me and the NFL to say, ‘Hey, dude. This isn’t good for you to go out and do it again.’ I’m not saying he saved my life. But who knows what would’ve happened if I would’ve tried to go out and play?”

All along, NFL Life is nothing like Civilian Life. Kolb recently had this conversation with friend, and current Bills backup QB, Case Keenum. NFL life, he told him, is “exaggerated.” The highs are too high. The lows are too low. There’s “deception,” there’s “glory.” It’s not normal. Not with millions of people studying your every move, Truman Show-style. Not when one wrong decision gets you cut the next week. The pressure is intoxicating to one extreme; suffocating to the other.

Transitioning to a life that’s stretched out, that’s more about delayed gratification is not easy.

That’s why Kolb believes so many players hang on as broadcasters, as coaches. Not that there’s anything wrong with that. It’s a primal instinct and, often, lucrative. He’s had offers himself. One major television network asked Kolb to interview for a job. He turned it down. One team extended an opportunity to coach quarterbacks in 2019. He turned this down, too, and it was not easy. All Kolb says is that this was “a very special quarterback in a very special situation.” Briefly, he wondered if his four girls would enjoy the euphoria of a Super Bowl win.

But he’s not looking back.

Kolb’s a busy man today in Granbury, a serial entrepreneur who maneuvers in the business world like Josh Allen outside the pocket.

The majority of Kolb’s time is spent in real estate and development: residential, commercial, industrial, even ranches. At the moment, his group is developing nearly 10,000 acres. He estimates they’ve done about 350 million in revenue the last seven years. He owns a construction company and is busy with an Internet company, “Linxus,” that provides wireless to West Fort Worth. Kolb also runs four autism clinics in the North Texas area. “Thrive” focuses on 1-on-1 therapy with kids ages six to 12. Several parents have told him the program changed their kiddos’ lives.

Kolb heads up the men’s ministry at his pastor’s church.

And, mostly, he enjoys being a Dad to his four daughters: Kamryn (14), Atley (13), Saylor (10), and Parker (six).

He calls them ranch girls who can shoot a gun, bow and arrow and fish better any boys in any locker room. Kolb is positive his girls have made him a better man. They’ve “tenderized” him. When his pal Smith was in town with his family once, Kolb was too harsh on Kamryn — and Smith was blunt. Told him he’d never talk to his daughter that way. Kolb agreed. This was wrong. An hour later, he dropped to one knee and grabbed his daughter’s hand right in front of Smith. “Daddy’s not perfect,” he told his oldest daughter. “I’m going to tell you I’m sorry and do it right in front of this big, burly man so you know that nothing’s going to ever stop me from saying I’m sorry and I love you. And you have to find a man like this when you get older.”

That big, burly man started crying. Smith told Kamryn how lucky she was to have Kolb as a father.

No way does Kolb do this if he had sons to rough up. All of these girls forced him to be the father they need him to be. “And,” he adds, “not the Dad I pictured myself as.”

Word of Kolb’s turnaround got out. This isn’t a world glamorized on ESPN or NFL Network. But exactly like former quarterback Ryan Leaf, he became a force of positivity paying it forward to fellow NFL retirees. His phone’s always open. Kolb gets calls from players at 11:30 p.m. — bawling, begging for help, falling off that “cliff.” It’s common for them to unload all emotions from a locked bedroom, lights off, away from all family members.

“Strong guys,” Kolb says. “Guys you know. And it’s gut-wrenching.”

During these conversations, Kolb explains how their identity is wrapped up in football. And that means adopting traits and habits you cannot even see yourself.

He’d know. He was in their shoes that drive from Guthrie to Granbury in ’14.

“The world is telling you how great it is. The game is telling you how hard it is. The money’s telling you everything is OK. When, really, it’s not,” says Kolb. “So when you get done, the money’s not what you thought it was. And the world is gone — the world’s not telling you anything anymore. Football’s gone. That was your identity. What do you have to fall back on? That’s when a lot of marriages start to struggle. That’s when a lot of kids start to get verbal abuse. And guys like myself start to sink into depression.

“It’s a combination of so many things. People need help.”

Kolb shares words of wisdom to anyone who needs him, all while his own future is a mystery.

He harbors no illusions that he’s in the clear himself.

There’s one symptom he cannot shake. Anyone who’s cracked business deals with Kolb gets used to the former quarterback putting on a pair of sunglasses during meetings. Lights still give him trouble. Once he took the elevator up to the 32nd floor of a building in Houston to pitch an oil-and-gas deal to a private equity group.

He didn’t care that the billionaires looked at him funny. He needed these shades to soothe the pain.

When he gets “scatterbrained” — and his memory flickers — he knows it’s probably a result of those concussions. He tries not to give them too much credit, yet never dismisses them. Brain damage has inherently changed NFL players. Kolb realizes there may be severe consequences. When? Beats him. His plan is to push the worst of the worst ailments down the road by staying active. Many ex-players whose concussions have triggered depression, and even suicidal thoughts like Jamal Lewis, insist it’s imperative to fire those brain neurons.

Lewis is also moving nonstop in business and fatherhood. Colledge is a director of development at Boise State, his alma mater. Smith built a gym in Knoxville, “Triple F Elite Sports Training.” Most NFL players are Type A and obsessive compulsive and addicted to the drug of competition, Smith explains. Punching in-and-out at a typical 9-to-5 job is akin to taking a placebo. He knows serial entrepreneurship has been critical to Kolb’s happiness.

“There’s a reason there’s so many homeless veterans out there,” Smith says. “There’s just nowhere you find a true brotherhood of competition and loyalty and friendship you get in that sport. At the end of the day, he’s a dang good man. Dang good father. Dang good Christian and just wants to better his family’s life and better people's life around him. To say that Kevin Kolb has transitioned out well, especially the way that it all ended, would be an understatement.”

If new science emerges, Kolb is all ears. He’s doing spinal therapy right now and says it’s awakening areas of his body.

It’s true that the NFL has taken steps in the right direction for current players. No longer is the expectation to throw some dirt on that brain and play on. Whether the Arizona Cardinals said so or not, that was life for Kolb in 2011. Thankfully, that’s not life for players in 2023. The NFL still isn’t fully owning concussions as part of the sport. Perhaps you’ve noticed that TV partners now say players are being treated for potential “head injuries.” Rarely concussions. As if a brain jiggling around the skull is akin to a twisted ankle. Too often Roger Goodell and the owners seem to care more about what Mom’s thinking at home than being authentic.

Maybe those at the top still aren’t being completely honest. But players can be.

So, that’s Kolb’s message: Be honest. Be open. Value long-term health over the short-term pressure to play. The worst of his four concussions in four years was the second — the one he concealed — because that’s the one that sent him into a state of isolation. Team and player must be on the same page.

“The isolation and darkness and depression that comes with the confusion of a concussion on the player himself,” Kolb says, “is just as bad as a concussion in my opinion.”

More players may walk away from the sport two or three years early to preserve their bodies and brains, too. Like Colledge.

He chose to retire after nine seasons. He was 33 years old. A man who started 137 of a possible 141 games. Teammates like Kolb are why Colledge left millions of dollars on the table. He didn’t want to risk more brain damage and he didn’t want to endure five knee surgeries like so many ex-linemen. He wanted to be able to play with his kids in his 50s.

“I knew what I was doing was going to shorten my life and that there would be consequences,” Colledge says. “The league wasn’t done with me. I was done with it. Some guys like Kevin luckily grab a bag of cash — but what he had to deal with to get that bag? He’ll have to deal with that for the rest of his life. That saddens me.”

To others, the risk is always worth it.

Every player must follow his own compass.

Kolb is aware of Tua Tagovailoa’s plight. The Dolphins’ rising star suffered two concussions (possibly three?) through the 2022 season alone and was eventually shut down. Once he recovered this offseason, the 25-year-old quarterback took up jiu-jitsu to learn how to fall more gracefully because, much like Kolb taking those knees to the head, Tua’s head trauma struck on plays that were strikingly benign. His helmet bounced off the turf. No infomercial on state-run TV, no rule implemented by suits on Park Avenue fix this. All the league can do is pray Tua stays upright and play the probability game. It’s no coincidence that the Dolphins — a highly entertaining team in a large market — received only three primetime games. Half as many as Buffalo, Dallas, Kansas City and the L.A. Chargers. Even the Jimmy Garoppolo-led Las Vegas Raiders received five.

One can only imagine if Tua has engaged in the same conversations with his wife, if he also believes he’s one strike away. Last season, the two welcomed a son into the world. The good news is head coach Mike McDaniel has publicly maintained that Miami will keep Tagovailoa’s health a top priority — the team was killed for how it initially handled its QB. Everybody’s watching. There will be no Kolb-like isolation. Also, credit the Dolphins for providing Tagovailoa financial security by picking up the fifth-year option on his rookie contract for 2024, a fully guaranteed 23.2 million.

For now, Tagovailoa is as gung-ho as Kolb was exactly one decade ago.

He watched his concussions on film and believes the training is working, noting that tucking in his chin is No. 1. Tagovailoa also shared at his April presser that neurologists told him CTE would not be a problem. They said the disease is more prevalent in players banging their heads against something persistently. Such as linemen, linebackers.

He isn’t looking back, and that’s his right. Free will is what makes this the greatest country on earth.

Kolb will be watching.

“Obviously,” he says. “I am concerned for him.”

The key today is continuing to live this honest life. Kevin Kolb accepts all challenges ahead. Speaking so freely gives him a sense of freedom. He’ll need to deal with symptoms regardless, so why hide? By discussing everything with men at his church, his wife, his kids — all of you reading this — Kolb avoids the isolation and depression that comes with his reality. He’s the opposite of a recluse.

Stories of ex-players battling CTE in their 40s, 50s, 60s are often terrifying. Kolb is 38. It’s impossible to predict what lies ahead. Maybe the prospects are brighter for quarterbacks. It’s true they absorb fewer subconcussive hits over time. Genes could also worsen Kolb’s odds. His mother’s sister died from onset dementia three years ago. He witnessed her health deteriorate “to the point of death” and fears resurfaced.

Is this something my family will be battling with one day?

Are they going to be doing the same thing with me? Do I prepare them for it?

And then Kolb made sure his daughters know the truth about his head trauma. He plotted all worst-case scenarios with his wife.

“They have the freedom, if I’m unsafe, to do this,” says Kolb, ominously. “You don’t have to walk me to the grave. It’s fine. So, again, being open and honest about what could come but also not living in fear.”

Indeed, Kolb soldiers into the great unknown devoid of dread. He feels liberated. The picture he took of his No. 4 Bills jersey in the Redskins’ visiting locker room still hangs on his office wall. The memories of all concussions remain vivid, not suppressed. He’s got no problem supplying all detail from the moments that changed his life. At no point does Kolb actively attempt to steer our conversations toward a more pleasant direction.

The only regret he has is not telling anybody about Concussion No. 2. When it comes to football itself, he has none.

“I would sign up tomorrow for it again.”

But… why?

We’re all struggling to square with our love for the sport when Damar Hamlin receives CPR, Tua’s hand locks up and another round of players are loaded onto a stretcher. The unique violence of the sport has been trumpeted in these pages umpteenth times, from Matthew Judon’s alternate dimension to Wyatt Teller’s pancakes to the Detroit Lions’ gnarly offensive line. Even after all of the injuries he sustained on the field, Kolb embraces the gladiator nature of football. It’s the pressure and the money, he says, that “manipulates” the sport he loves.

Kolb repeats he’d still sign up tomorrow because football gave him tools nothing else in the world can.

“I just didn’t combine them with what God was trying to tell me,” he says, “and I didn’t combine them with good people around me.”

Kolb wishes he could go back in time to put the entire package together. Then, he pauses. He wonders if that’s even conceivable, if it’s even realistic to operate this way because of the mental focus the NFL demands. So, again, he repeats that guys simply need to ask for help. This cuts against the grain of how they’re trained to live in the sport. To play through anything. Especially when a backup is on deck to steal your paycheck. But the more “communication,” the more “circulation of information,” the better. Nobody involved can afford to stick their head in the sand. Owning this darker side will allow future players to more smoothly navigate a path to everlasting happiness.

Kolb is living proof. He believes he’s stimulating the damaged areas of the brain. People keep telling him he’s sharper than ever.

The darkness that came with concussions, on second thought, was always worse than the concussions themselves. Much worse.

Removing this darkness changed his life.

“We need to diagnose what we can handle: the depression, the isolation, the financial issue, the support. The change in lifestyles,” Kolb says. “That’s the stuff where we really need help. Because we’re going to be fighting these injuries — and everybody has some sort of scars and injuries, not just football players — but let’s fight those.”

And that’s the juxtaposition that pissed Leaf off. On draft day, there’s Goodell giving you a bear hug. But when you’re done, he said it becomes, “Don’t let the door hit you on the ass on the way out, kiddo. Good luck.” No player should be subjected to the nonsense Kolb endured with those doctors. Billionaire owners will launch flowery initiatives around whatever The Current Thing is that given month on social media, but when it comes to treating former players with dignity after head trauma? Suddenly, they’re coming up with lint.

Concussions are not a fixable problem. Not unless this transforms into flag, and good luck getting fans to tune into that product.

What is fixable is how the NFL handles its own reality. There are an infinite number of changes owners could make: eliminate the preseason, guarantee more money, shoot “Thursday Night Football” to the sun. Above all? Educate current players and assist former players. Because even though his NFL career was a cataclysmic series of events, Kevin Kolb knows he’s one of the lucky ones.

As he speaks down in Texas, birds chirp and a rooster crows.

Yesterday, Kolb flew to a ministry event. Today, it’s back to business and most of his companies are well-oiled machines by now. He doesn’t need to micromanage, instead doing hands-on work that can change lives. Shortly after this phone call, Kolb will sit down with a gentleman who’s going through a hard time. He’ll pass along many of the life lessons shared here. On Friday, he’ll get quality time in with his girls.

He wants to help anyone he can. Football player or not.

Kevin and Whitney shared a meal with a young couple just last week and, afterward, the young husband across the table told his wife, “See, I told ya!” When Kevin asked what he meant, the kid said he had never met a human being living the life he was put on earth to live quite like Kevin. “You have so much intentionality with everything you do,” he said.

Kevin Kolb can’t lie.

Hearing those words felt pretty damn good.

Outstanding! An expertly woven story that reminds me of your eye-opening Favre article from the old JS days. Part II is eagerly anticipated.

The quality of the Favre piece was what first got my attention. “Hey, this kid writer is really good. I mean REALLY good.”

After eventually having lost track of both you and Bob McGinn after your respective departures, blue chip reads became less common.

Go Long found me through Linkedin, not the other way around. Thanks to a bit of serendipity I rediscovered top shelf journalism - unvarnished, honestly comprehensive, uncensored, unbiased, and with courage and conviction not to serve as anybody’s propaganda huckleberry for the company buck, fame, and the undeserved promotion. This is one person who craves more independent journalism across the board.

Thanks for keeping journalistic integrity alive. What’s still left of it that is. Lord knows there are those out there who are doing all they can in their power to monopolize information released.

From the world of sports, of all unlikely places perhaps, hope shines brightly. Never quit!

This story is perfect example of why I subscribe here. Feel awful for Kolb.