Damar Hamlin is why we love football

One final thought on the Buffalo Bills safety's remarkable recovery. Professional football players are a different breed.

How easily we forget that sinking feeling of horror. The unknown. All of us struggled to justify our relationship with football the night of Jan. 2, 2023.

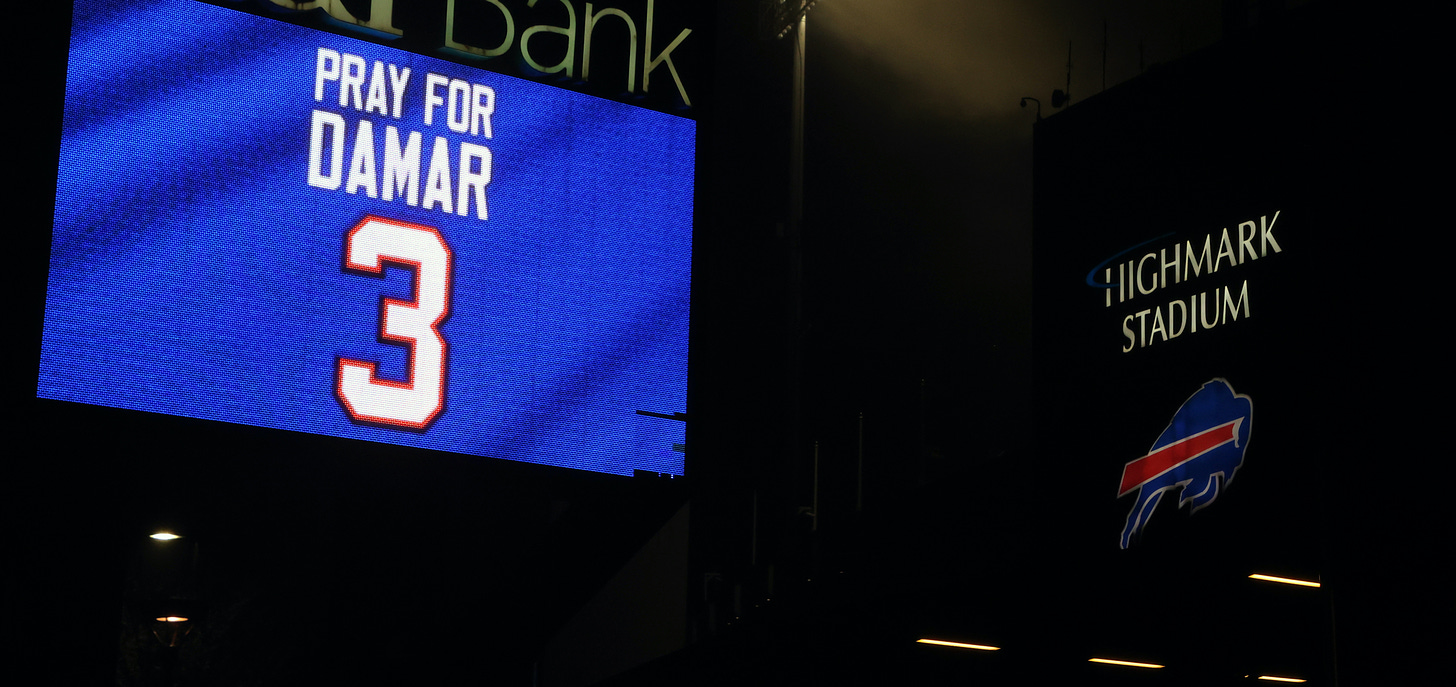

Damar Hamlin’s heart stopped on the field. CPR shocked him back to life.

His body was transported to UC Medical Center. Nobody had a clue what was next.

Around midnight, I wandered around the Cincinnati Bengals’ field to contemplate an unprecedented moment. What was next for this sport? If Hamlin died, how could anyone step onto a field again? All we could do was wait for updates out of that hospital, and band together. Our country — whose inhabitants typically spend time online gnawing at each other’s throats — united in historic fashion. More than $9 million in all was donated to Hamlin’s foundation.

Three months later, Hamlin has announced he plans on playing football. Incomprehensible back at Paycor Stadium.

“This event was life-changing,” Hamlin said on Tuesday. “But it’s not the end of my story. So, I’m here to announce that I plan on making a comeback to the NFL.”

Any activity that nearly kills a person is usually the last activity that person would voluntarily partake in again.

Football players, however, are different.

The raw violence of the sport is more siren song, than caution flag. We love this sport because it’s not for everyone. These human beings are as close as we have to modern-day gladiators and, if I learned anything writing “The Blood and Guts,” it’s that no amount of flags and fines and bureaucratic gobbledygook from paranoid owners will ever change the fact that this is the most violent team sport on the planet. There is no utopian middle ground. The league’s worst injuries today occur on stunningly ordinary plays — like Hamlin’s tackle of Bengals wide receiver Tee Higgins, like Tua Tagovailoa banging his helmet upon falling. Until the NFL is full-fledged flag football, there will unfortunately be many more eerie moments of silence.

Hamlin is obviously the most extreme case. Players know the work hazards going in, but never anticipate their heart stopping on the field. The Bills safety said Tuesday he suffered commotio cordis, a direct blow to the chest that causes cardiac arrest.

Doctors have cleared Hamlin, so he’ll voluntarily hurl himself back into that 1-on-1 situation vs. a wide receiver. Buffalo even plays at Cincinnati again this season.

And this is why we watch — 99.9 percent of Americans wouldn’t even think about stepping back into such an arena. Hamlin will. Hamlin wins Comeback Player of the Year for even pulling into One Bills Drive for the team’s offseason conditioning program. His story turned from tragic to triumphant.

Go Long is powered by our readers. Thank you for joining our community.

George Kittle articulated the profession best in B & G. The San Francisco 49ers tight end has always viewed football as “its own living and breathing organism.” A lesson from Dad. You must “respect the grind” of the sport, he said, to reap its rewards. Because the sport knows if you truly love it, if you appreciate its essence.

Here are words we’ll never hear during the next Football is Family infomercial.

“At the end of the day, football is a violent sport,” Kittle explained. “You need to be violent to play it. There are violent things that need to happen for you to move the football down the field. That’s just the way it is, and it’s never not going to be like that. Otherwise, it’s going to be flag football.”

What makes the sport so special is exactly what the league seems intent to eradicate.

The problem was never the grisly sight of injured players on a field, rather the league refusing to own those grisly sights. From its concussion denial through the 90s to the maddening roughing the passer penalties today, like most corporations, the suits in charge are concerned about optics more than reality. If 32 owners could ever accept that football is inherently violent — that, yes, the violence could compel a parent to steer their child toward soccer — it’d eliminate quite a bit of B.S.

At least, it’d be an exercise in honesty. Even concussions are now referred to as “head injuries” during broadcasts.

We shouldn’t hold our breath, considering hypocrisy is their specialty. Look no further than the gambling advertisements spamming your life.

As much as the league sells this profession as more of a cheeky reality show, it’s ruthless. Hard Knocks will never be a true reflection again. As Kittle joked, it’s not normal for grown men to beat each other up during a training camp practice — throwing a few punches in the 90-degree heat — before then slipping into a cold tub to discuss each other’s families… while fighting for a job… while knowing one injury at any moment could render you expendable to the front office. Football is loaded with physical and mental pressures alike that Kittle battled to the extreme back to his Iowa days. Anxiety could’ve destroyed his career before it began. A sports psychologist recommended the tight end draw a big red button on his wrist tape. That helped. After each play, good or bad, he hit it to “reset.”

Players all find unique ways to handle a profession unlike any other.

Most hang on for as long as they possibly can. They’re essentially peeled off the field, before broadcasting or coaching and clinging to football (and all of its virtues) any conceivable way. Football supplies so much joy, so many life lessons that other sports frankly cannot.

Good luck finding a retiree with regrets. It doesn’t matter if it’s Ben Coates, who now struggles to walk around his own North Carolina home. Or Jamal Lewis, who has battled suicidal thoughts. Or Erik Kramer, who’s been to hell and back. Or another ex-quarterback we’ll feature soon at Go Long who suffered a string of horrifying concussions. Again… and again… and again… even those inflicted with lifelong pain from this sport insist they’d do it all over again. Often, they cite the sport’s unique camaraderie and the fact that there’s no habitat in nature like an NFL locker room. It’s a sacred place. Other times, they cite how the sport set their family up for life financially. And long before millions of dollars filled his charity’s account, a rookie safety named Damar Hamlin told us he wanted to give kids back in his McKees Rocks, Pa., neighborhood hope.

More than half the friends he grew up with have died. The sixth-round pick wanted to be a source of light.

His why was very clear.

“I try to be a big voice for them,” Hamlin said that night over wings at Elmo’s in Getzville, “because I know what they’ve been going through. I know how hard it is. So I’m trying to push them, keep it positive and let them see me. Let them see it’s possible — ‘I come right from where y’all are from.’ … It’s a lack of opportunities. You’re in survival mode.”

By surviving his own near-death experience on a field, Hamlin has already accomplished a lifetime’s worth of inspiration. His presence alone unquestionably saved lives in McKees Rocks — and beyond. There’s no need for Hamlin to come within 100 miles of a professional football field.

Yet, there he was at One Bills Drive with his teammates. Running and lifting weights and trying to put the weight back on that he lost. In his mind, there are more kids to inspire. That’s how we can all reconcile supporting this sport. Football is a vehicle for so much good in the world. The league is full of Hamlins inspiring neighborhoods across the USA.

Hamlin could continue his world tour and charge whatever he wants for speeches.

But he’s back. He’ll strap on that No. 3 again.

The sport’s combatants know no other way.

Why Damar Hamlin is exactly what the Buffalo Bills need

The light in football's most horrific hour

Podcast: Damar Hamlin, life and football

ICYMI…

Bob McGinn’s 39th Annual NFL Draft Series has begun with Part I, a close dissection of this year’s wide receivers and tight ends.

Would you draft Jalen Carter? On the podcast, Jim Monos and I discuss character risks and how those conversations go down in draft meetings. (Also available on Apple and Spotify.)

Here is how Florida quarterback Anthony Richardson becomes a star.

Substack Notes has arrived! Interact with fellow Go Long subscribers — and readers across the Substack network — on the platform’s new social-media feature.

A chat with Ron Wolf, the Hall of Famer and architect behind the Green Bay Packers’ revival.

Mailbag! Did the Miami Dolphins close the gap this offseason. Your questions answered.

'No surrender, no retreat:' Jody Fortson, a Buffalo story.

Good to hear Damar is ready to return. It would be useful and educational for fans to learn the cause of Lamar's cardiac arrest and subsequent corrective treatment if any. More than likely it wasn't a football injury, but instead an abnormality in his heart structure which caused a cardiac rhythm disruption. If in fact, it wasn't football related and he has received a treatment to fix a heart defect or prevent a reoccurrence, it will help reassure fans that he's making a smart decision and not risking further injury. Hopefully, Damar or someone on the Bills staff, can provide some insight to these questions.