'No surrender, no retreat:' Jody Fortson, a Buffalo story

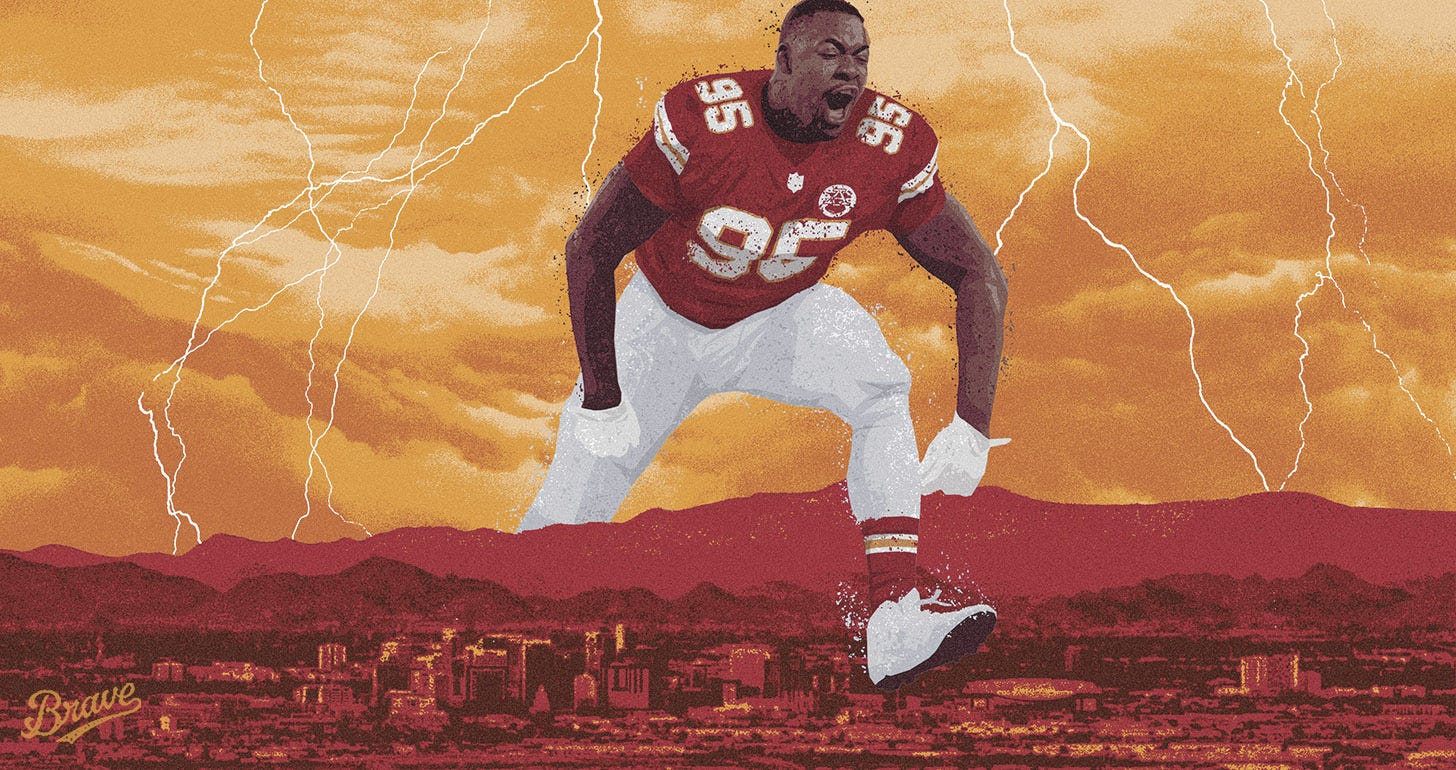

How does a kid who scored all of one high school touchdown, who bounced JUCO to JUCO, get to this point? His city, his uncle, endless belief. Now, the Kansas City Chiefs tight end will take flight.

BUFFALO — He resembles football royalty. A conquering hero who has returned home in a sleek purple track suit, a gray blanket draped over his shoulders and a blinding “JF” necklace.

Jody Fortson is back where it all began. His city. At 6-foot-4, 226 pounds, it’s impossible to miss him.

He spoke to students earlier this day and, considering they started calling him “hope dealer,” Fortson’s optimistic he changed a few lives. He spent time with family, with friends. From ducking through the doorway of an aunt’s home that used to seem so big to seeing peers doing the same exact thing they were a decade ago, this is always humbling. And to cap his trip off, Fortson needed to visit the Chiefs backer bar in Buffalo. Remember the clip of Patrick Mahomes that went viral? When the Super Bowl MVP appeared to drunkenly hand the Vince Lombardi Trophy off to a fan? That hardware was actually a replica… straight from this bar. The owner of Casey’s Black Rock, Vinnie Garofalo, flew out to KC with his dead-ringer of a Lombardi and broke the Internet. Fortson cannot wait to get his hands on the hardware.

But first, he reflects. Everything that led to this day is mind-boggling.

A kid who hardly contributed in high school and junior college and D-II ball somehow fought his way onto the best offense in the NFL and won two rings. We first met in Phoenix. Three days before the Chiefs outlasted the Philadelphia Eagles, 38-35, Fortson detailed much of his rise at the team hotel before making it clear we needed to reconvene in Buffalo. So here we are. He sets Super Bowl Ring No. 1 on the bar. Then an AFC Championship ring. The expectation is for Fortson — dressed to the nines — to justifiably peacock as the local kid who defied all odds to reach the football mountaintop. To throw back a few cocktails and, I don’t know, stump for Byron Brown to give him a key to city.

Immediately, however, Fortson strikes the polar-opposite tone. He doesn’t order any drinks, any food, instead cutting right to the chase: Fortson is sick and tired of hearing “Congratulations!” and “Wow! Look how far you’ve come!” Everyone in this City of Good Neighbors has been very nice. Kindness from friends is appreciated, but never any insinuation that this is as good as it gets. Anyone assuming this is The End is wrong — however well-intentioned.

“I want more. I want a bigger role. I want to be the man,” Fortson says. “All of this celebratory stuff? That’s all it is. It’s only going to last another week and a half, and I don’t want to hear it anymore.”

Yes, he has caught four touchdowns in two seasons. Yes, Fortson supplied the critical block on Kadarius Toney’s game-changing punt return.

The Super Bowl was not a capstone.

“It becomes insulting,” he continues, “because I know what I’m capable of and I know what I can offer this game. Hearing everybody say, ‘Be happy!’ Bro. Stop talking to me. I don’t want to hear what you have to say because you’re not on the same level of frequency as me. Because I want more and you’re complacent.”

Fortson believes he hasn’t accomplished a damn thing in this sport yet. He’s dying to show the world everything he can be as an NFL Tight End. Because, honestly, he has zero clue what it’ll even look like. (“How do you put something that hasn’t been seen before into words?”) All he knows is that his play style will be a blend of “pure excitement” and “entertainment” and “joy” and most importantly… “passion.”

He begins to picture everything he’ll become in 2023. His scowl brightens into a smile.

“Every time I’m on the field,” he says, “it’s going to ooze out of me. You can’t hide passion, in any realm, any field.”

Rhetoric that seems hyperbolic until Fortson starts tapping open plays from Chiefs practice on his phone. Right there on his screen are circus catches that could build a congregation of believers. So… how? How did Fortson get to this exact point, at a Chiefs bar in Buffalo, N.Y., harboring dreams of becoming The Next Big Thing at tight end? A handful of preps reached the NFL from Buffalo — Steven Means (Ravens) and Isaiah McDuffie (Packers) are still playing — but nobody has his story. There’s a good chance Buffalonians never even heard the name “Jody Fortson.” He caught all of one touchdown in high school. One. He then toiled in anonymity from Hudson Valley CC to Erie CC to Valdosta State before appearing out of thin air in the NFL.

No wonder Fortson asks us to “respectfully” never compare his journey to anyone else’s from Buffalo.

Yet, the more he explains the impossible, the more it’s obvious Fortson is a direct reflection of the city itself. A city that endured so much catastrophe in 2022 alone: The Tops shooting that killed 10. The December blizzard that left 47 more dead. An earthquake in February. Locals don’t wallow in defeat here — they attack life with zest, with positivity. And the raw spirit of the city itself is clear in Fortson, a man who’s had many reasons to quit.

“Which way are you willing to take it?” Fortson says. “It’s what’s in you. Buffalo is in me. That grit. That toughness. I’m not surrendering. No surrender, no retreat. That’s Buffalo.”

The reason he never surrendered is the same reason he’s so unsatisfied.

He still hears a man’s voice in his ear, the voice of his uncle: Barrie “Yummy” Woods.

Go Long is dedicated to longform journalism in pro football and completely powered by our readers.

Thank you for joining our community:

Everyone who grew up in Western New York has their own lake-effect storm story. A stuck truck. A broken snow blower. A white-knuckling whiteout on Route 219. God forbid what happened to anyone stranded this past Christmas.

Jody Fortson is no different. He was 10 years old when parts of Buffalo received 24 inches in October 2006. Looking outside of his window, in awe, there was at least a foot that AM. Sidewalks weren’t plowed yet. His mother’s brother spoke up. Woods instructed his nephew to strap up his Timberland boots and start running laps around the block because it’d strengthen his ankles. Huh? Come again? There were no cars, no humans at all outside in the freezing cold. Fortson didn’t protest and, soon, this became a habit. After growing up on the east side, he moved to Altruria Street in South Buffalo around eighth grade. That’s when Fortson started running around Delaware Park at 6 a.m. Didn’t matter if it was five degrees or 95.

Early dreams of becoming the next Kobe Bryant quickly changed. Seeing how aggressive his nephew was on the court, Woods convinced Jody to pour his energy into football. He started playing organized football for the first time that fall of ’06 which, ironically enough, was the last time Fortson played tight end before the NFL.

Granted, the coach could only feed him the ball via reverses because he couldn’t catch.

“I used to not be able to catch a cold butt-naked in Alaska,” Fortson says. “It was so bad.”

Woods, the man raising Jody, believed nonetheless. Always. In reality, it was more than pure belief.

“Not only did he believe in me,” Fortson says, “but he put the work in. It’s one thing to say, ‘That kid’s going to make it. That kid walking up and down the street, dribbling a basketball every day, he’s going to make it to the NBA.’ But to actually put the work in with him? To make sure he doesn’t lose the passion? The hunger for this? And he stays focused and he doesn’t get worried about everything on the outside and this is his main focus right here? That’s a different level of commitment. My uncle had that commitment.”

The commitment didn’t end with those trudges through the snow.

Friends enjoyed summer day trips to Six Flags Darien Lake. Fortson embraced his uncle’s boot camp.

Ten to 15 yards away, Woods was forever the human JUGS machine missiling footballs as fast as he possibly could. (“Hundred miles an hour,” Jody says.) If he dropped a ball, nothing needed to be said. Jody immediately dropped to the concrete to do 20 pushups. On his knuckles. Woods told him that feeling of raw pain would eventually stop him from dropping the ball again. Quarterbacks in the NFL, he promised, will throw the ball way harder than this — that Jody would thank him one day when he’s in the Super Bowl, when there’s a zero percent chance he drops the ball on the game’s grandest stage. The breakthrough moment was a catch a mere two centimeters above the ground. Fortson faceplanted into the concrete, but he caught the ball and never dropped one from his uncle again.

Whenever football practice at school was over, Fortson usually had a second practice back home.

He knows his ruthless competitiveness comes from Woods, too, assuring Woods would route up anyone on a football field. Toddler or grandmother. He took no prisoners, he showed no weakness. In NBA2K, he would embarrass him… 110-20. In Madden… 56-12. Jody cried, broke more controllers than he remembers and never was allowed to quit.

He wasn’t perfect. He got whuppings — everyone did — but his whuppings weren’t nearly as bad. Instead, Fortson received what he calls “workout punishments.” That is, he’d stand in the corner of the room while holding three phone books above his head on his toes for however long was asked. His calves burned. His shoulders ached. He was 6 years old. (“That’s why I can jump out of this world.”) Or he’d do squats. Or more pushups. Creative forms of discipline lasted up to age 18.

“My sisters had to go to their room, but me?” Fortson says. “I have to stand in this corner for two hours holding this phone book. It’s crazy. … He had a vision.”

Woods was creating a monster on the football field. That’s why Fortson implores the Dads out there to get creative. Next thing you know, he says, our daughters will turn into Simone Biles. (“You’ll have a gold medalist!”) The reason Woods became a father figure, a big brother, a protector all rolled into one was that Jody’s biological father was in the military. Father and son are still tight today. Upon returning to his offseason home in Atlanta, Jody planned on driving to see his pops in Savannah. They’ll be taking a fishing trip together soon.

Dad retired from the Army two years ago, right before Afghanistan was handed back to the Taliban. Those images of Afghans clinging to the wing of a plane still give Fortson visible chills. His father was deployed in countries throughout the Middle East and, once, stationed in Alaska. Jody was 12. That’s when Woods convinced him it’d be smart to get outside of his Buffalo bubble and live in Alaska for a year. Woods knew it’d be a good thing for Jody to realize there’s a bigger world out there.

He was right. Fortson calls this one of his best decisions ever. He spent the year in Fairbanks, Ala., attended Tanana Middle School, and befriended military kids from China, Korea, Japan. He didn’t play a down of football that year, but he did go tubing and sledding and take field trips and… avoid wild moose. They’re as common as dogs and deer, he says. Quickly, Fortson learned it’s best to escape angry moose in a zig-zag pattern. They are not gentle creatures.

“They will walk you down,” he says, wide-eyed. “They’re not slow, either. Keep your head on a swivel. Head on a swivel!”

Fortson returned to the states determined to do damage on the football field.

Only, he was a total nonfactor in high school football. Forget social media buzz. Sifting through the agate archives of The Buffalo News for any mention of Fortson is a “National Treasure”-like quest.

He wasn’t a factor until his senior year and, even then, Fortson is described as “an average, maybe slightly above-average player,” by South Park head coach Tim Delaney. South Park threw for 2,000 yards through a 4-5 season, but Fortson was merely a third or fourth option as the slot receiver to the left side. He ran in-motion. Caught some bubble screens. Blocked. Never was overly dynamic with the ball, the coach admits. One wideout caught 40 balls but the wealth was spread around to everyone in their scheme, thus Fortson had all of 18 receptions for 241 yards with that one lone touchdown in his final high school game. Delaney remembers the play vividly — a quick out on the backside vs. Williamsville East — because he was so happy Fortson finally scored.

There are no herculean tales to share. Nothing remotely similar to the footage of Chiefs teammates. Delaney is correct to cite Fortson’s Hudl clips as “normal-looking high school highlights.” Mainly because Fortson was not the physical specimen he is today. That final year of H.S, he stood only 6 foot 1, 180 pounds. Similar to NBA great Dennis Rodman, who famously sprouted from 5-11 to 6-7 after high school, Fortson’s growth spurt was (freakishly) late.

Delaney does remember Fortson as a force at the forefront of everything South Park was trying to build as a program, saying he helped instill principles that remain “ingrained” 10 years later.

“He was still a work in progress,” Delaney says. “It’s a testament to, not only his ability, but his will to work at it. That’s a story we always want to point out to our kids. You might not be recruited. You might not be highly recruited. Everybody might not be able to look at you as being successful in whatever path you choose. You have to keep going that route.

“It’s a super interesting story that anybody — whether you’re an athlete or not — it’s something you can look at and say, ‘It’s possible.’”

South Park was founded in 1915 and launched a football team immediately. To Delaney’s knowledge, Fortson is its only student to ever play in the NFL.

“Not because of anything we did as a program,” Delaney adds. “He did that work.”

Jody was unfazed by his lack of P.T. because his uncle was unfazed. One stinkin’ touchdown and Woods still believed his nephew was NFL-bound.

“He never let me doubt myself,” Fortson says. “Even when I didn’t get any offers out of high school. Everybody wanted to go Division I. He never let me feel like I wouldn’t make it. He never let me feel like I wasn’t enough. My uncle changed the course of my life.”

Both at that Chiefs team hotel and here at Casey’s Black Rock, specific memories spontaneously crack Fortson’s voice. Like recalling his uncle’s energy. It was different. “Yummy” was skinny and fragile with “a big heart,” Jody says. His personality was infectious — the man could’ve been a comedian. He was persuasive. Even though no scholarship offers filled the mailbox, Fortson chose to believe that the NFL was a realistic goal. He headed off to Hudson Valley Community College in Albany to audition for D-I schools.

Then, something strange happened.

In February 2014, Fortson read on Facebook that his uncle was missing. Initially, he didn’t think anything of it. He assumed his uncle was taking care of business somewhere. Maybe Ohio. Days passed, then weeks. He continued to train. The longer his uncle was missing, the more Fortson began to worry.

Finally, he saw on Facebook that his uncle was found.

Seconds later, his phone rang. It was Mom.

When his mother first stated that her brother was “found,” Jody Fortson was relieved. He asked where his uncle had been this whole time.

That’s when she clarified. No, no. Authorities “found him, found him.”

As in murdered. Gunshot wounds. He was 32.

Thinking back, those precious moments that followed remain a blur. Fortson remembers blacking out, hanging up the phone, staying awake all night. He trudged to the football facility to work out shortly after 5 a.m., and he couldn’t. He bawled his eyes out. His coach told him to go home and spend as much time as he needed with family. Fortson was heartbroken but, once this burst of tears was wiped away, he genuinely did not believe the news. Not until he saw Woods laying in the casket with his own eyes.

His uncle was shot dead while leaving a Super Bowl party on Feb. 2, 2014.

Twenty-one days later, his body was found off Main Street in North Buffalo.

Four specific moments should’ve forced Fortson to surrender — this was No. 1. Nothing was more traumatic than losing the man who believed in him. His entire family was mourning. They lost a brother, a son, a cousin which made it difficult for anyone else to actively lift Fortson out of his own sorrow. He allowed himself to grieve for a while but knew he couldn’t “stay stagnant,” couldn’t lay in his bed all day with the blinds down.

Right then is when Fortson realized how much the city of Buffalo was inside of him. (“You can’t be from Buffalo, he says, “if you’re not tough.”) Before, sure, Fortson wanted to play in the NFL. But now? He had zero choice. His focus reached a new level because his uncle was quite literally the only person who believed playing professionally was even possible. He remembered how Woods would aggressively shout down anyone who dared to disagree.

He pressed on.

“I already had the fire in me but it just grew times a thousand,” Fortson says. “It made me take this so much more serious. I really don’t have a choice now. I’m going to die about this. My fire is still growing. I’ve got something to prove — and not to anybody else. Mainly to myself. And to prove my uncle right. Because my uncle told me I was going to be the greatest. So, I’m not stopping until I’m the greatest.

“It’s that simple.”

The next year, he could’ve quit again.

In Buffalo, his mother fell down the stairs and broke her hip. Fortson was forced to leave Hudson Valley for Erie Community College, right across the street from the Buffalo Bills’ stadium. It would’ve been easy to trash those football dreams and find a job to support his mother. She wasn’t working at the time. As he drove those four-plus dreary hours on the New York State Thruway, Fortson wasn’t sure if he’d even be able to play football at ECC. He needed to show D-I schools something on film. Anything. Lord knows there wasn’t any high-school tape for them. The only reason Fortson was getting a lick of JUCO interest was that he was built like an NBA player.

He remembers speaking to God on the I-90. Seeking answers.

Mom had a total hip replacement. She’s good now. (“Still feisty,” son says.)

He did play at ECC, but the best way to sum up this 2015 pit stop? Fortson’s most memorable moments came in an 82-10 loss to Lackawanna (Pa.) College.

ECC’s head coach, Scott Pilkey, had just taken over the program after working at the University at Buffalo. He cobbled together a group of 120 kids from other JUCOs, local high schools in a matter of five months and ECC went 6-4 that first year. Albeit with two wins by forfeit and the others over schools any D-I school would devour like Tic Tacs: D-III Brockport’s JV team, the Globe Institute of Technology, etc. Considering ECC was a bottom-barrel program for eight years, however, this was substantial progress. Pilkey cites Fortson as a driving force because he worked so hard… with one needed wake-up call.

Years later, inside Pilkey’s office, Fortson told the coach that one of the best things he ever did for his career was bench him.

Pilkey cannot even recall the final straw. Only that in trying to build a team from scratch, he needed to make an example out of anyone who missed a practice or was a “me” guy. Fortson was growing — fast — as the “best-looking athlete” on the ECC field. Fortson was extremely passionate. But after some “minor issues,” coaches told him to sit one game.

“He said to me that was the defining moment for him,” Pilkey says. “He felt like, ‘Wow. I could really lose this.’ He really couldn’t. Trust me, I wanted to play him. … It was a reset of his mindset. He said, ‘Whew. This is something — even at the junior college level — that can be taken away from you. That really impressed me. He knew how fragile what he has is.”

Pilkey never had a problem with his players being pissed off. He liked Fortson’s fire. But he needed him to earn his way back in, and the wide receiver did. He refocused. He learned how to play in his new frame. Pilkey still remembers when he told one of his 5-foot-9 corners to jam Fortson at the line of scrimmage in practice. The two teammates talked smack, fought to the ground after the whistle, and the next play? Fortson got separation and took a slant to the house. Pilkey says Fortson’s body awareness is in the top 1 percent of anything he’s ever seen.

The numbers were again pedestrian (29-374-3), but Pilkey detected a special wiring.

So many people today view Fortson as a “peripheral guy” who came into focus late and Pilkey says those people have it all wrong. The NFL was on his mind all along.

“And I think it’s a Buffalo trend,” Pilkey adds. “We’re not New York City. We’re Buffalo. There’s a ton of things here we get beat up for but there’s a ton of things here people don’t know about unless they’re here. We hunt for opportunity.”

That’s swell and all. His stat line and grades still prevented any D-I schools from caring. He received zero scholarship offers. That’s why Fortson cites this as the third moment he could’ve quit. All heartache, all sacrifice… for what? Pilkey knew a coach at Division-II Valdosta State (Ga.) University, so the flame on those pro dreams wasn’t extinguished yet. His size got him noticed. (Again.) But his playing time was sporadic. (Again.) In 2016, still at wide receiver, Fortson caught 23 passes in 10 games. One player who did take him under his wing was a cornerback named Kenny Moore. He, too, was driven by NFL aspirations. Fortson will never forget one specific practice. He caught a crosser and Moore had a clean opportunity to, well, “smoke my head off my shoulders,” Fortson says. This isn’t the NFL. Vicious collisions were common.

Moore, however, pulled up. Spared him. A simple gesture Fortson never forgot.

Then, in 2017, Fortson could’ve quit for a fourth time. Academically ineligible, he was forced to sit out the entire football season. The sentence easily could’ve boomeranged him 1,100 miles north to Altruria Street. Instead, Fortson hit the books and made the dean’s list to give himself one final chance to get noticed by NFL scouts as a senior.

Another bad break followed. On the cusp of that 2018 season, Fortson pulled his hamstring and missed six games. His final stat line was hardly worth the ink of an area scout’s pen: 14 receptions for 217 yards with three touchdowns. Valdosta State did win the Division II National Championship and Fortson did catch a 16-yard touchdown in that 49-47 victory, a hint at his potential. Immediately after scoring, Fortson pointed up to the sky. But this college career never went according to plan. No coach, no mentor entered his life and paved a yellow-brick road. No singular game got him noticed. There was no Combine invite. No local pro day. Fortson needed to run at Kennesaw State’s pro day to draw the eyeballs of anyone in NFL.

It all made him.

All Fortson had was his uncle’s belief. And Buffalo. And that was enough.

“I literally don’t even know how to start the process of quitting,” he says. “Not this. Especially not this.”

As for his uncle’s killer, a police investigation provided no answers. When asked if anyone figured out who did this, Fortson says he believes somebody got to the perpetrator. (“Somebody, somewhere.”) Retribution was likely. That’s not what gave him closure.

“I got my closure not because whoever did it got dealt with — or whatever happened with them,” Fortson says. “I got my closure because I know my uncle is at peace. I know he’s not here physically but he’s still here with me. I feel him all the time. His presence. Leading me in the right direction. I feel him — ‘I’m proud of you.’ I’m thinking about all the stuff I overcame, and all of the times I could’ve quit. He would’ve been like, ‘Boy! If you don’t put your big-boy drawers on… let’s go!?’ My uncle was the truth. He really was the truth.”

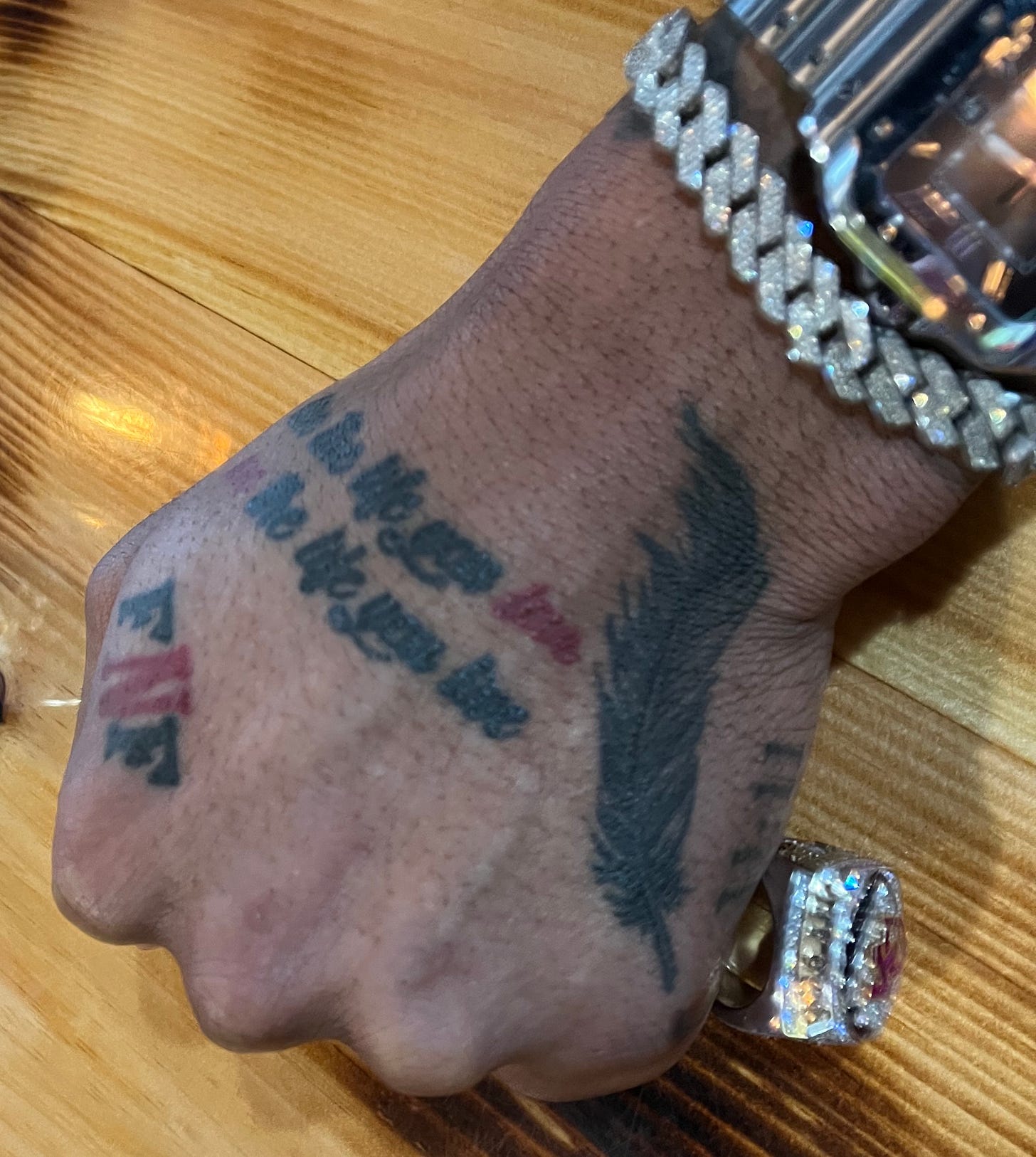

Underneath this track suit is a body covered in art.

He’s got tattoos of Allen Iverson, Kobe Bryant and both a butterfly and a bee as homage to Muhammad Ali. His favorite is the one he received right out of college on his right bicep: an unbelievably detailed portrait of his uncle in his signature Cleveland Indians flat-brim, the one Woods wore so much that people thought he actually played for the baseball team. This tattoo kept the NFL dream alive. Fortson wanted his uncle to see every catch. He told Woods he’d have the best seat in the house.

Only two teams were interested: Kansas City and San Francisco. After speaking to his pastor and his Mom, he decided to work out for the Chiefs.

Four years later, here at Casey’s Black Rock, Fortson stares up at the television screen. This year’s NFL Combine is currently being broadcast. Fortson never had a chance to perform on that stage but he also knows those prospects on the screen trying out for NFL teams weren’t running laps in a snowstorm. Fortson does not believe they possess the same “I’d die for this…” mentality.

Another batch of rookies are out to take his job. He can’t allow it. His eyes don’t leave the screen.

“You all have to come see about me,” Fortson says, “because I’m not done! I’m not done. I’m still not done.”

To this day, Jody Fortson has no clue what made Jody Fortson appealing to an NFL team. Nobody with the Kansas City Chiefs has explained why he was even in town for this three-day rookie minicamp. Yet, there he was with the team’s 2019 draft picks… and UDFA signings… and returning practice-squad players… and other young vets who had already bounced around NFL locker rooms. Fortson was here on a tryout basis and, typically, only one or two tryout guys eek onto the 90-man camp roster. Most are here to fill out drills.

He was also playing tight end for the first time since 2006.

It was disaster.

He lined up wrong, repeatedly. He ran the wrong routes. He made a slew of mistakes each of the three days and thought for sure he was a goner. Yet those rare instances in which he did line up correctly on a play, Fortson’s raw athleticism was obvious.

“One thing’s guaranteed,” Fortson says. “I’m going to go make a play.”

He taps his phone open to reveal one such play that weekend in 1-on-1 drills vs DBs. “I jump up,” Fortson says, “and grab the ball in this miraculous kind of way.” A movie teaser that sounds hyperbolic until he hits play and you see No. 44 take off up the right sideline and do exactly that. It’s not even a Chiefs quarterback throwing him the ball, rather 2019 coaching intern Dan Williams. (To his credit, Williams graduated with a slew of passing records at D-III Stevenson University and throws a nice ball.)

Fortson made the 90-man roster and was stashed onto the practice squad. He didn’t hesitate to let everyone know he was in the NFL to stay, either. It’s one thing to make the 53-man roster as a UDFA, win a Super Bowl as a rookie and get the Super Bowl ring tatted on your neck, like former Packers corner Sam Shields. It’s quite another to get the NFL shield plastered four weeks into your life as a member of the P-squad, making $10K’ish per week. That’s what Fortson did the week of the Chiefs’ game in Detroit. Teammates gave him hell — “Bro! Are you serious?” — and Fortson promised he was here to stay.

Six years to the date of his uncle’s death, Feb. 2, 2020, Fortson won a Super Bowl. He spent the next season on the practice squad with coaches unsure if Fortson was a wideout or a tight end. Either way, he kept dropping jaws. That August, three-time All Pro Tyrann Mathieu was even singing his praises after Fortson plucked a one-hander over him. Out of respect, Fortson rarely ever shares this video clip with anyone. The Honey Badger is why he wore No. 7 in high school. He doesn’t want to embarrass a player who’s meant so much to his own life.

He does supply a sneak peek at Casey’s and, yes, it’s nuts. The definition of “posterized.”

He scrolls through his phone, finds another play, hits play. There’s Fortson toasting starting corner La’Jarius Sneed with an outside release. Backup quarterback Chad Henne lets it rip and Fortson clowns another NFL starter. One-hands it right over Sneed’s head while tightroping the sideline. “Both feet,” he points out, “are inbounds.” Patrick Mahomes is special, but throws like this one is why Fortson tells people all the time Henne is disrespected. Both he and Matt Moore loved lobbing jump balls to him.

“Any time you see me in a red helmet,” he says, “it’s me doing something crazy. … If you give me a shot. I’m going to make sure you’re on top.”

In 2021, he was elevated to the roster. Fortson had five receptions for 47 yards.

In 2022, he caught nine for 108. Including this 40-yarder on a nifty wheel route in primetime.

Every day, his uncle’s words of wisdom stick with him. Woods used to remind Fortson to put his happiness first because life’s short. So, Fortson had the words, “Live the life you love and love the life you live” tatted on his hand. Woods demanded he lift an extra two reps in the weight room. So, if a bench press with the Chiefs calls for 10 reps, he busts out 12. When it’s down to eight, he does 10. Every time Fortson thinks his arms will give out — bench, curls, squats — he conjures enough strength from within to do more.

He’s grateful for the Chiefs’ patience. They molded him, he says, “like clay.” Quick to say he doesn’t owe KC — or anyone — anything at all, Fortson does appreciate their belief. Learning from one of the game’s best tight ends ever in Travis Kelce has been a blessing. But that tint of frustration in Fortson’s voice is unmistakable. As he replays those clips on his phone, he notes that the Chiefs see this every day, adding “it’s practically unfair at this point.”

Unfair because Fortson knows the Chiefs know he’s ready to be a force in their passing attack.

“Obviously we want to win at the highest level,” says Fortson. “But I didn’t sign up to this game to be mediocre. I look at my stats, and I’m not happy with any of them. I’m not going to be complacent and act like these rings are making my career. No. Because that’s not how I see it. I want to be great. Really great.”

College websites listed him at 6 foot 6, the Chiefs at 6-4. The Jody Fortson on this cell phone screen looks seven feet tall. If that player is unleashed on NFL Sundays, the possibilities are endless. Those are the athletic plays that got his tight end forefathers noticed.

All of which drew from their own specific sources of motivation.

Tony Gonzalez changed the position more than anyone. Undersized as a Pac-10 basketball player, he learned how to rebound and time up jumpers against players who towered over him. When it was time to win a jump ball vs. a 5-foot-10 DB? Forget about it. In “Blood and Guts,” he traced his ability to dominate to slaying this fear within because, as a kid, he was relentlessly bullied. Dallas Clark was everything the ultra-, ultra-demanding Peyton Manning wanted in the Indianapolis Colts’ high-tech, high-octane offense. He traced it all to losing his mother in his arms before then walking on at Iowa, where he mowed the grass at Kinnick Stadium, sold the campus newspaper and served as a test dummy for psychology students. Jimmy Graham fought for his life as the runt inside of a group home. He’ll never forget the feeling of his face breaking. Rob Gronkowski treated the football field like all of the epic Mini Sticks hockey battles with his brothers.

Those plays from KC’s practice field? Fortson can also draw a direct line.

Holding up those phone books wasn’t easy. His ankles hurt in the snow. Look closely and maybe you’ll even find an old scar on a knuckle.

“My uncle,” he says. “Simple and plain.”

Those rings on the bar top are nice and all. It’s time for his own star turn. After getting tendered by the Chiefs — one year, $940K — Jody Fortson now enters the most important year of his football life. More than ever, he’s demanding greatness from himself.

That’s what his uncle would want.

Fortson appreciates locals raving about his block on Toney’s 65-yard punt return in the fourth quarter of that Super Bowl win. He also didn’t work so hard, so long for a shove of an Eagles punter to serve as his career highlight. This Buffalo homecoming provided further clarity.

“I’m not satisfied. Not even close,” Fortson says. “I’m an athlete. I catch touchdowns. I jump over people. And dunk on people. Did you see that during the Super Bowl? I have something else to show. I’m an athlete. A route runner. A pass-catching tight end.”

The next evolutionary twist to the Chiefs’ offense could be nightmarish two-tight end sets — Kelce and Fortson working in conjunction.

He hopes Andy Reid believes.

“I’m going to show you why your belief is right,” Fortson says. “I’m going to show you. At times, Coach Reid has shown me he trusts me a little. I feel like every time my number is called, I make a play. Hopefully, it grows. Hopefully, he gives me more trust.”

His favorite moment from Phoenix was seeing rookie Skyy Moore score his first career touchdown. He’s never felt this much joy for a teammate, sprinting onto the field to smack the rookie on the back in the end zone. After going 18 games without a TD, Moore finally got into the end zone through what proved to be a pristine second half. Fortson calls this coaching staff “untouchable” because his head coach Reid had every answer to every question.

Don’t mistake hunger for anger. Fortson enjoyed the Super Bowl afterglow, partying for a solid four weeks. As for details? All he’ll say is that the dark shades were on, he was pumping his fist and the music was loud. A trip to the Bahamas follows this chat.

Then, it’s back to training. His uncle’s voice still rings loudly. Whenever he doesn’t feel like working out, he’ll hear a booming: “You’re being soft!” Fortson also claims that many of the people loving him up on this trip home today were hating on him yesterday — “disrespect” that fuels him. He has no wife, no girlfriend as a man very much married to the sport at 27 years old. A close bond that brings to mind a different tight end forefather. Jeremy Shockey might’ve lived on the back page of those New York tabloids but he viewed relationships as a distraction. He once told Reggie Bush that he would’ve been a Hall of Famer if he didn’t date Kim Kardashian.

Even those times Shockey did go out in the city, guilt seeped into his conscience and he’d bang out 100 pushups at 3 a.m. He had a delirious passion for the sport.

Fortson enjoys fashion and has even dabbled in modeling but feels a similar magnetic pull.

Maximizing this moment — in 2023 — matters more than anything in his life.

“Passion is all I’ve got to give to this game,” Fortson says. “Passion and relentless hard work. I’m going to turn it up a notch.”

It’s this passion that Western New Yorkers can relate to most. His rise is far more relatable than any road glistening with scholarship offers and NIL deals and SEC stadiums packed with 100K fans. He’s self-made. He’ll share every detail with every kid that wants to hear him. “No secrets!” he says, because he wishes somebody would’ve come to school to help him.

After speaking at South Park High School on this trip, he connected with one senior whose mother died earlier in the week due to pregnancy complications. The student, Antonio Watts, played in a playoff basketball game the same night. Chatting with Fortson gave Watts hope.

Delaney was present for the heartfelt address to the kids. What stood out most to him was Fortson explaining how he never forgot what he truly wanted through all ups, all downs. The crux of his rise is straightforward.

“Everybody says they want to do it,” Delaney says, “but are you willing to do the things that it takes to get there? Jody was. For him to go to junior college, go to Division II, play his way onto a scholarship role, get the chance in the NFL, make the practice squad, then make the team, battle through an injury, it’s a one-in-however-many-you-can-say kind of stories. It really is a testament to him.”

Adds Pilkey: “Jody built this piece, by piece, by piece, by piece. If he had part of his life shattered, guess what? He brought that with him. If he didn’t do well in the classroom, guess what? He brought that with him. He was sat down. I don’t remember why I did it. I wanted to help a young man learn a lesson. He brought that with him. … He’s earned the right to be who he is today because he brought it all together.”

If Fortson was able to inspire one student at South Park High School, that’s enough. He knows it won’t be his last. Each catch, each touchdown will only escalate his role as that “hope dealer.” He believes there’s as much talent in Buffalo as any city in Florida, in Texas, in Georgia. The difference is athletes returning to their neighborhood to show it’s possible.

That’s why he always dreamt of this opportunity.

“Because what is it to make it out of here, if nobody else does?” Fortson says. “If I’m the last NFL player to come out of Buffalo, then I didn’t do my job.

“That’s all it takes — a little bit of belief.”

He’d know.

Before taking off, Fortson collects those rings on the bar and realizes we had an audience this whole time. Behind us, at a high top, sit a grandfather, son and grandson. They heard everything. The grandson — holding that Lombardi replica — poses for a picture with Fortson.

Chances are, he’ll remember Fortson’s voice for a while.

Go Long is completely independent. You can support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber today:

Other Chiefs stories at GoLongTD.com…