Man in the mirror: Alim McNeill explains the Detroit Lions

One year ago, the defensive tackle stared at his own reflection and didn't like what he saw. Now? He's the key to these Lions going on a Super Bowl run.

ALLEN PARK, Mich. — The stench is gone. After three full seasons of WWE-like draft celebrations from the general manager and more damage to the vocal chords of the head coach than we could possibly imagine, it’s Morning in America. The Detroit Lions are on the cusp of winning their second playoff game since 1957.

Take care of the Los Angeles Rams this weekend and the Detroit Lions are two wins from the Super Bowl.

Those chosen few who lived through the misery weren’t sure they’d see the day.

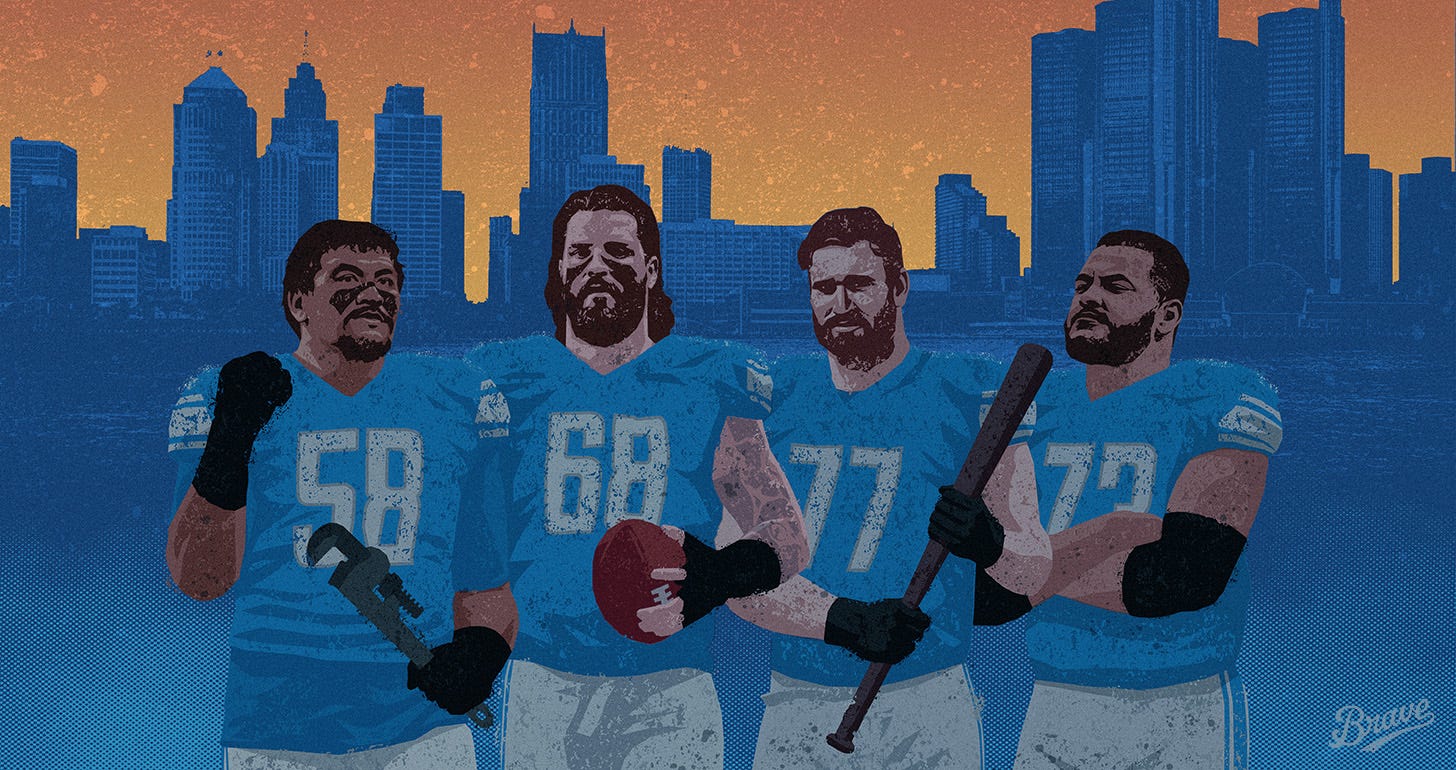

On Sept. 14, 2022, in an office adjacent to the locker room, the team’s longest-tenured player dreamt of this opportunity. Go Long was in town for a two-parter on the Lions’ snarling, bat-wielding offensive line when a poignant left tackle Taylor Decker articulated the state of the team: “We’re just getting those bits of losing stench out of here. And we have to get it all out. We need everybody to believe.” He continued: “When things aren’t going well, you can’t let that losing stench seep in and embed itself in your organization and your culture.” He was hopeful. He wasn’t certain. Subconsciously, players were still bracing for inevitable calamity.

Decker nailed the fragile line between winning and losing. It’s psychological. One bounce, one catch, one call too often torpedoed the Lions into woe-is-me dread. He knew the Lions needed to vanquish this subconscious impulse.

Back in the same room, 441 days later, sits a lineman from the other side of the ball: 6-foot-1 fireball Alim McNeill. When I bring up Decker’s assessment, he immediately jumps in to assure that the stench is gone. For good. “One hundred percent.” Now, the Lions expect to win as the clock bleeds in the fourth quarter. Now, if something does go terribly wrong — if the Lions, let’s say, are hosed by the officials — they are not strangulated by self-pity. Players move on. Coaches move on. The path to this point, he admits, sounds cliché.

“Work, work, work, work, work,” McNeill says. “We put in the work. We knew what we wanted to do this year and we bought into each other. But we worked. We worked like maniacs, and it’s paying off.”

When the Lions’ 9-8 season in 2022 concluded with a bang at Lambeau Field, players made a vow to each other to return in the best shape of their lives. Normal protocol. The sports world is inundated with Best Shape Of My Life tales every offseason. But when the Lions reconvened for OTAs in the spring, players realized immediately this was quite abnormal. McNeill insists players looked different. Moved different. The 2023 Lions would attack this season with genuine purpose.

He’d know.

He was the ultimate maniac.

Go Long is your home for longform in pro football. The NFL playoffs are here. Be sure to access all stories, all podcasts at GoLongTD.com as a subscriber.

Your support directly fuels our independent journalism.

Before McNeill headed home to Raleigh, N.C., last offseason, he stood in front of the mirror. He was 335 pounds, right where coaches preferred. But McNeill didn’t like what he saw in the reflection. His face was puffy. He felt bloated, unhealthy, and knew he had zero chance of playing at this weight for the next 10 years. McNeill was barely able to squeeze his face into his helmet, and it was no secret why. His diet consisted of pizza or chicken wings — “whatever was closest and fastest.” Don’t even get him started on the Chick-Fil-A two miles from the facility. He knew that spot like the back of his hand. But he also knew this lifestyle was costing him plays on the field. A split-second slow penetrating off the line of scrimmage. A split-second late lunging at a running back. McNeill could tell in the moment that he was out of shape.

For no reason at all, McNeill was staying awake until 1 a.m. many nights.

Major changes were needed.

So, that day, McNeill took a blue marker and wrote the following words directly on the mirror: “I will never look like this again.” He stared himself down, scowled, demanded change. Back home, McNeill started training three times per day, going to bed by 10 p.m. at the latest and completely changed his diet. Out was pizza. In was a grilled chicken sandwich with a salad and a water.

The next time he looked in that mirror, he weighed 305 pounds.

Says McNeill: “I just made my mind up: ‘There’s nothing that’s going to stop this.’”

Now, he’s the ultimate variable. Alim, pronounced “ah-LEEM,” is the player who both explains how the 12-5 Lions got to this point and how the Lions can keep on winning.

The destructive defensive tackle was building an All Pro resume before spraining his right knee. In 13 games, he totaled 32 tackles and five sacks. Statistics hardly explain his impact. The Lions offense is fine, from quarterback Jared Goff to the full repertoire of weapons to the man pushing the buttons. But, defensively, McNeill’s absence was glaring through December. To mount a playoff run, Detroit desperately needs a push up front. Football — at its fundamental core — is a test of your largest men moving their largest men the opposite direction. Shy of dusting off Robert Porcher, holding open tryouts or trying to sneak an extra two pass rushers on the field, the Lions have tried everything. They even lured a pair of 36-year-olds off the couch at various points in edge rusher Bruce Irvin and tackle Tyson Alualu. Maybe James Houston, “The Problem,” rockets into the lineup but he doesn’t sound quite ready to return from the broken foot he suffered in Week 2.

Detroit’s secondary has been stammering for weeks. Coordinator Aaron Glenn needs to rattle Matthew Stafford — and any QB who’s next — without sacrificing bodies blitzing. Poor Aidan Hutchinson (11.5 sacks) has become a magnet for double teams. Somebody up front needs to dominate a 1-on-1 matchup. Plain and simple. It’d make everyone’s life better on defense.

Otherwise? Quarterbacks will warp playoff games into flag-football contests.

The key to a Super Bowl run is the man with a “DIFFERENT” tattoo inscribed on his right arm.

Alim McNeill is, indeed, a different defensive tackle seeing a very different game.

He was not the archetypal high school athlete who put on 75 to 100 pounds over four years of college like Zach Sieler, like Cody Mauch, like so many offensive and defensive linemen who realize quickly that the pathway to NFL success involves a lot of food and a lot of dumbbells. McNeill was always a big boy. Even in high school, he weighed 295 pounds. But he also could freakin’ move. He wasn’t a lineman, no, McNeill played middle linebacker and running back on the football field and right outfield on the baseball diamond. When the school’s strength coach laser-timed him in the 40-yard dash, he clocked in at 4.6 seconds. McNeill knows that sounds farcical. But when he ran the 40 a second time, the digital readout was the same: 4.6.

Since swinging a bat in T-ball at age 4, he expected baseball to take him furthest. This was his first love.

Baseball, to him, is like chess. A thinking man’s sport. He could spray the ball to any part of the field but McNeill was more Prince Fielder than Ichiro. More of a power hitter. He cherished the game within the game, trying to get inside the mind of a pitcher each at-bat. What pitch is next — a fastball? A curveball? A change-up? Sacks are fun but they’ll never compare to the euphoria of belting a home run over the fence. That home run is the sweet result of winning such mental warfare. Through his entire athletic upbringing, it was baseball that sharpened McNeill’s mind. No. 1, he notes that everyone who has ever played the sport is bound to slip into a hitting slump at a young age.

He remembers his. His hand-eye coordination was all out of whack at age 9. McNeill could not touch the ball.

“But once you do and you’re able to track it in and see it and get your hands on it?” McNeill says, “Baseball is really, really underrated as far as the mental aspect of it.”

The key is reaching a point where you’re not overthinking. Just swinging. And swinging. And instinctively recognizing pitches in real time. His travel team in Raleigh was elite. He’ll never forget his first dinger. His club was in Georgia for a game against “Team Miami,” a group full of talented Cubans who didn’t speak English. Nothing beats the sight of a fastball down the middle. “If it starts looking like a beach ball?” he says. “That’s when you know you’re about to smash a baseball.”

His size always snuck up on offenses at middle linebacker. But on to N.C. State — where the plan was to play baseball and football — coaches swiftly moved McNeill to the D-Line.

Lining up in a three-point stance was foreign to him. Initially, he hated it. He hated not being able to scan the field and use his mind in the middle of the mayhem. Still, it only took McNeill one week to get the hang of this new position. That soon, McNeill calibrated his footwork with his handwork and grew to enjoy a new mental challenge on the field.

Mental stimulation is a must.

Whereas most kids his age enjoyed playing “Call of Duty,” McNeill wanted to know how everything on the screen was even possible. The nitty-gritty tech behind the phones, tablets and computers we all take for granted. “What engine is this running off of?” he’d wonder. “What type of software this is running off of. How is this running?” Fascinated by software development at a young age, he earned a degree in science, technology and society at N.C. State in three years. The plan is to intern at Microsoft whenever he’s done playing football and to create his own software.

To those whose laptop has been shutting down for no good reason with a haunting Whoosh! sound, McNeill offers a grave warning: It’s about to die for good. Back everything up on a hard drive before it’s too late.

He has one other hobby, too. McNeill also goes by “Dream,” the rapper.

He listens to a ton of artists for inspiration, including Don Toliver and Drake. But McNeill? He doesn’t curse or use any violence whatsoever in his lyrics. He knows his parents and his little cousins are listening and McNeill also doesn’t want to invent a life that never existed. He grew up with both a Mom and a Dad inside a loving household. His older sister played travel softball, his younger brother played football and baseball. This very-safe, very-idyllic childhood didn’t resemble anything he was hearing in the mainstream. And that’s OK. Music still became a perfect release.

His personal favorite is “War,” which he describes as a pump-up song before games. Another is “Flowers.”

“I just talk about my experiences,” McNeill says, “and try to relate with people that relate with me.”

Maybe he’ll even rap one day about the collegiate baseball career that ended before it began. McNeill was on N.C. State’s baseball roster, all set to play the spring of his freshman year. But with three to four games per week, McNeill was also enrolled in an English class he could not miss. Students were only permitted to miss two classes the entire semester, he explains. Miss more than that and you’ll flunk.

He’s certain the academic advisors — who were part of the football team — did this all on purpose.

“I told them to give me English in the summer so I could get it out the way and just go from football to baseball,” McNeill says. “But they didn't do that. I really think they did it on purpose. … I hated it. I wanted to play baseball so bad.”

McNeill had no choice but to give up baseball. He didn’t push back because he didn’t want to be the new kid making a stink. McNeill even lied to his Dad in saying it was his decision to focus on football because he knows Dad would’ve hightailed it right to campus. Nobody ever explained why they snuck English into that spring semester, but honestly? N.C. State did Alim McNeill a favor. He did enough in college — 77 tackles, 10 sacks, one hilariously fun tip, pick, touchdown — for Campbell and GM Brad Holmes to draft him in the third round of the 2021 draft.

All of this created a unique threat at a unique time in Detroit Lions history.

There’s no doubt: Without baseball, McNeill isn’t in the NFL.

Hand-eye coordination at the plate translates to hand-eye at the line of scrimmage.

“Reaction. Timing,” McNeill says. “Being able to track a baseball in, you’ll be able to track a block or a football. And then playing in the outfield, that’s athleticism. Showing you can track the baseball. But I’d say the biggest thing is hand-eye coordination.”

If your hands and feet are not synchronized, you’ll wind up on your back. “A guarantee in his league,” he says. Thankfully, he doesn’t even need to think about where to shoot his hands because he’s done it so much. It’s natural.

“Now, I see a block coming,” he continues, “I just throw my hands on it. It’s just normal. Repetition, repetition. But that hand-eye coordination is from baseball. It has helped me tremendously. I can see things. Everything is kind of slowing down for me. I am able to see different things a lot better and use my hands honestly. It is really simple, but at the same time it’s not.”

Typically, defensive linemen must win in a quarter of a second. When the ball’s snapped, your first step is crucial. Technique is paramount but the McNeill Advantage is his mind. Rewind to the Lions’ 31-26 comeback win over the Chicago Bears on Nov. 19. That game, he possessed an intimate knowledge of the offensive guard blocking him play to play: Nate Davis. The two trained together in Los Angeles for a stretch last offseason. He knew Davis would jump-set him aggressively, and stands up to demonstrate. Davis would literally “jump” at him to create a stalemate, to stop McNeill from even getting into his move.

Rather than fight it, McNeill set him up. He strategically made a point to stay outside whenever Davis jumped him. He didn’t counter, simply staying on Davis’ edge in the B gap. “I would just stay there,” McNeill repeats. “Whatever he did, I would just stay on the outside move.” Play… to play… to play, Davis walled off his ‘ol training partner. Little did he know that McNeill was lulling him to sleep. With 1:06 left in the first half — on third and 6 with Chicago in the red zone — it was time to strike. The defensive tackle unleashed an inside club move, trashed Davis with his right arm and crunched quarterback Justin Fields to force an incompletion. The Bears settled for a field goal. Into the second half, McNeill laid another trap. With the threat of an inside rush now established, he eventually spun outside to sack Fields.

“That’s the mental part of this,” McNeill says. “Setting up different moves to hit later in the game.

“That really kind of gets you going for the rest of the game, too. Because you’re in his head now. You’ve got him thinking.”

No different than baseball. No different than seeing that fastball spinning right down the middle. The second McNeill saw Davis leaning before another jump-set, he told himself: “I got you.” Like a pitcher back in his baseball days, an offensive guard only has a few options. Rushing the QB as an interior defensive lineman is a matter of knowing when to swing for the fences. On certain plays, he’s got a certain assignment. But McNeill mostly has the freedom to engage in such cat and mouse within Aaron Glenn’s scheme.

After this game, McNeill became the first Lions defensive tackle since Ndamukong Suh in 2014 to record five sacks. If not for the injury, he might’ve doubled this number.

And these plays are only possible because of that personal kick in the ass last offseason.

Which is everything Campbell seeks. He’s forever on the hunt for players who are intrinsically motivated. A wide receiver like Amon-Ra St. Brown catching 606 balls at the JUGS machine every week. A returner like Kalif Raymond who sent 800 emails to colleges on the slightest of slight chance one gives him a chance out of high school. A defensive tackle like McNeill who’ll train like a madman.

No coach told McNeill to change his body. But in Raleigh, training with N.C. State alum Ian Walker, McNeill made it a personal challenge to trim 30 pounds while still maintaining his strength. A typical day consisted of 30 to 60 minutes of footwork, an hour-long weightlifting session, defensive line drills and — to top it all off — McNeill would also rip through an ab workout or body-weight squats at home. Back in Allen Park, the Lions’ high-tech machine that measures a player’s leg strength revealed that McNeill hadn’t lost anything. If anything, McNeill is convinced he’s stronger.

Campbell can motivate. From Day 1, his speeches were legendary. But Campbell also knows true passion burns within.

McNeill sees a locker room full of players making the same sacrifices he did.

“Belief in each other. Belief that the guy next to you is going to do his job,” he says. “We’ve all been through the same thing here the last two, three years. We’re not as good. We're losing games. It came to a point with us: ‘We’re going to put this work in. Let’s turn this around. We’ve got to turn this around. We’ve got to start winning.’ And that was our mentality. We’re going into every game like we’re expecting to win now. We’re doing our job to the fullest of our abilities. We’re detailed. We’re not letting anything slip. Nothing goes unnoticed. We hold each other accountable.

“Obviously we haven’t done anything yet.”

That’s the greatest benefit of so much losing over the years. Nobody wants that stench, that feeling of impending doom to seep into their conscience ever again. All of the fake punts and fourth-down gambles and fourth-quarter defiance to win this 2023 season have changed the psychology of the Lions. But not in a braggadocios fashion. Good luck finding one player, one coach boast about anything.

McNeill won’t even declare himself one of the sport’s best interior players.

“Obviously I want to be the greatest,” he says, “but I don’t feel like I’ve done anything just yet.”

There’s power to dreaming, to saying the Super Bowl is the goal and not giving a damn who hears it.

In Detroit, however, there’s power in knowing how bad it’s been and never wanting to drift into that hell again.

“We know how it is on the other side,” McNeill says. “We’ve been on the other side. We were 1-10, 1-11. It’ll flip that fast. Each week, each game is a new week, new life, new game, new everything. And we know how that feels.

“That’s what we’re not trying to go back to.”

Last year, the Minnesota Vikings won the NFC North at 13-4. Their best defensive tackle, Harrison Phillips, admitted to us in the summer that film sessions were a bit too lax with ex-coordinator Ed Donatell. The 2022 season became so exhilarating, so unfathomable that the team’s shaky defense failed to thoroughly scrutinize itself. Mistakes were brushed under the rug. Contrast that approach with Detroit where, McNeill says, each of the four losses were slid underneath the microscope. They were truly “invested” in the loss.

Elite offenses now stand in Detroit’s way, starting with the 2021 Super Bowl Champs. Stealing possessions is a must for a defense that won’t morph into the ’85 Bears overnight. Detroit ranked 23rd in points, 19th in yards allowed and have only 41 sacks. This computer is constantly making that funky noise and shutting down without warning. The front office then pushes the power button and tries something new. Campbell and Holmes have been churning through various options on the D-Line since August due to injury, ineffectiveness. The best available option is seated right here. If McNeill is capable of baiting an opposing guard for one QB hit, one sack, one forced fumble to get the Lions off the field, that could be the difference.

The software wiz feels more mentally focused than he has at any point in his football life.

Watching players like Decker and Frank Ragnow and ex-Lion Michael Brockers behind the scenes led to that moment in front of the mirror. He realized they all must’ve been doing something right to last this long. Turns out, McNeill wasn’t alone. A slew of players attacked last offseason with the same ferocity to put Detroit in this position — the social contagion Campbell always craved. Players must take ownership.

He can give a rousing speech, but it’s on the players to bring it to life.

He can go for it on fourth down, but it’s on the players to execute whatever play is called.

As a result, the Lions no longer fear the worst. When the season is on the line, expect the unexpected. McNeill says Campbell sincerely believes in “every last one of us” and, by God, they love the fact that he’s actively trying to win the game instead of not lose it.

“He was born to do this,” McNeill says of Campbell. “His passion, his love, his detail for the game. And then him being a player as well, he understands us so he knows how to maneuver and how to do certain things. He doesn’t let bullshit fly. We have our fun and everything, but we don’t let no bullshit fly.

“Everybody’s held accountable. That’s what makes us a good team.”

Exactly how good?

We’re about to find out.

Lions features past: