The Detroit Lions Must Break You, Part I: Life and death

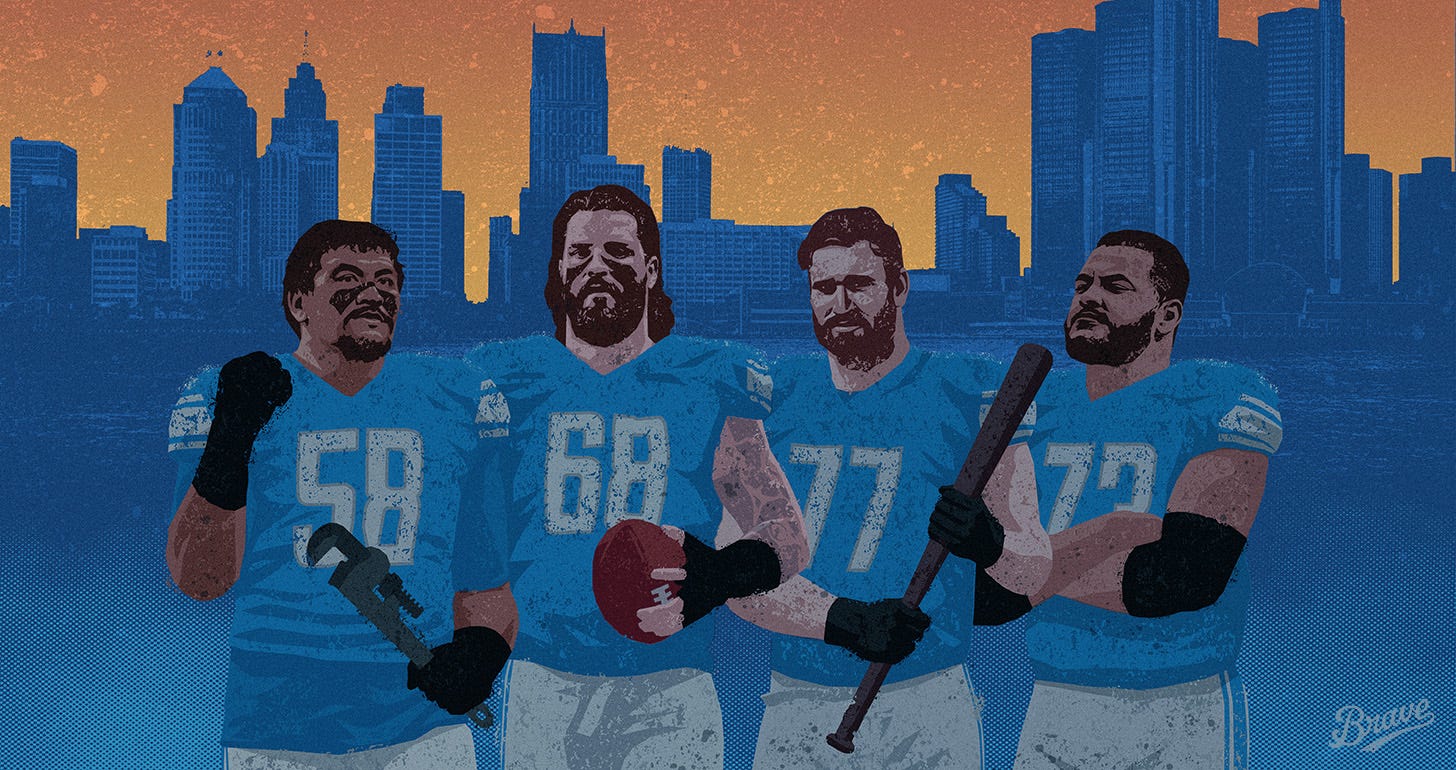

Meet the maulers bringing Dan Campbell's battle cries to life. This ass-kicking offensive line is preserving what we love about football. They just may turn the Detroit Lions into winners, too.

ALLEN PARK, Mich. — The soul of the sport is found right here. Take the thruway right into America’s Rust Belt, curve north into Michigan and every sight, every sound at Detroit Lions HQ brings you back to those Friday nights under the lights.

No words are minced here. The Lions want to stuff opponents into body bags. Their head coach has made his club’s intentions clear — repeatedly — and if his rhetoric makes anyone queasy? Please, by all means, go watch a soccer game. From Day 1, these Lions have taken every conceivable step to bring the sport itself back to its bloody roots. That’s been declared the formula for success by Dan Campbell.

At the dawn of this 2022 season, one week in, 21-year-old Penei Sewell takes a seat near the indoor practice field. Another weightlifting session is in the books and you bet these linemen still hit the bench and squat rack hard during the season. There’s nobody else around. Just this 6-foot-5, 335-pounder straight from a beach village in American Samoa with a tatted-up right arm gazing up at the banners celebrating the last three Lions teams to win a championship. The dates on these banners — 1957, 1953, 1952 — hint at breathtaking incompetence than anything. This franchise has won one playoff game since ’57. One. To change everything, this new regime made Sewell its first draft pick one year ago.

As Sewell looks up at those banners, he instantly thinks of the people inside the building today.

“I’m not only playing for myself out there,” Sewell begins. “I love to play with a purpose. And my purpose is those guys in that locker room. I’d die on the field for my teammates. I’d honestly do that. I honestly say that. Because they mean so much to me. Those boys and the work we put in together day-in and day-out? It’s something you can’t replicate anywhere else to be honest. You’re coming into the building at 7:30 and leaving at 8 p.m. That man is putting in the same work you have while feeling absolutely shitty. Mentally and physically.”

C’mon, Penei.

Die? For a game? You cannot be serious.

He repeats it once more — with heavy emphasis — to make sure everyone knows he’s not using hyperbole.

“I’d die on that field with them.”

Yes, life is different here on the Lions’ offensive line.

This is the group of players bringing all of those legendary Campbell soundbites to life, from the cannibalistic vow to bite off kneecaps at his introductory presser to telling fans “We are frickin’ starving … so the hyenas better get out of the way” to this gem during Hard Knocks: “We’ll tread water for as long as it takes to f--king bury you.” The man and the mission make sense when you examine the team’s foundation.

The Lions are still in the early stages of a wholesale rebuild that could lead to long-lasting success, but the reason none of us can take our eyes off this franchise right now is how they’ve gone about this rebuild. They’re not anti-analytic Neanderthals by any means. It’s simple: the Lions understand the sport isn’t won in a mathematical equation. Nor is this fantasy football. At its purest, football is violent and the best way to win a violent game? Impose your will. Bludgeon your opponent at the line of scrimmage. Or as offensive line coach Hank Fraley eloquently puts in his raspy voice during our chat: Stomp on his face in the mud. The DNA of the organization — and, in essence, the sport — is understood best with this band of badasses.

No team in the league places more of an emphasis on winning right where fingers break, groins pull, and, in the case of “Big V,” a back injury requires surgery all for approximately zero glory. Nobody cares if you’re mangled to bits. Nobody cares if you dominate an edge rusher for 68 of 69 snaps. Allow one sack and you’re tarred, feathered. Excelling on the offensive line takes a special sort of player — a man’s man who can handle this physical and mental toll — and, as Go Long learns, the Lions are building a machine that produces this exact specimen in high supply. The goal is for winning to serve as merely a byproduct of a team-wide lifestyle.

And these are the players establishing that lifestyle, Detroit’s new Bad Boys.

Only these Bad Boys — tackles Penei Sewell and Taylor Decker, guard Jonah Jackson and center Frank Ragnow — are much larger and can legally whup your ass. The unit’s fifth starter, Halapoulivaati “Big V” Vaitai, was placed on IR. Minor injuries have already dogged Jackson and Ragnow, too. But therein lies the point. What the Lions are building can withstand game-to-game injures. Down three starters, they still whipped the Washington Commanders for 191 rushing yards. In theory, this is what brings the Lions back for the first since Dwight Eisenhower was president, “Leave it to Beaver” premiered on CBS and two of the top songs on your radio dial were “Jailhouse Rock” and “Great Balls of Fire.”

In Part I, we examine the core four. The men who’d die for each other.

Sewell is the Maui-built demigod who should be toting around his own fish hook. He has broken the bones and souls of many challengers his first 21 years of life and labels himself the “Dennis Rodman” of the group.

Jackson and Ragnow both tap into their life-altering trauma.

Then, there’s the group’s conscience: Decker. He has a way of putting everything so perfectly.

“I’m not afraid to say that I love all those guys,” Decker says. “And I have their back out there on the field. Because we just do hard shit every single day and we do it together. You can’t replicate that bond in many other professions. Obviously, there’s military and other things like that. But it’s a deep bond when you go through hard shit together. I’ve been here for seven years now and it seems there’s been more downs than ups. Hopefully we come out of the back end of that stronger as a group.”

Decker takes a deep breath.

“I know we have guys who want to win. Me personally, I’m dying to win. Losing is the f--king worst.”

These Lions have been banging at the front door of relevancy since Campbell’s epic introductory press conference.

These are the players who can finally bust it down.

For good.

Malaeimi-made

The reality of a tsunami is far more chilling than anything portrayed in cinema.

Penei Sewell was not even a teenager, yet his memory of two specific tsunamis remains vivid. He grew up in the village of Malaeimi (pop: 1,000) on the tiny island of American Samoa. One of seven remote islands far, far, far away from the rest of the world in the middle of the Pacific Ocean between Hawaii and New Zealand.

The first tsunami hit when he was in elementary school. And luckily his school was only 25 steps max from his house. All the kids felt the earthquake — the ground literally shook beneath his feet — and Sewell sprinted home. Where, thankfully, there was a hill as high as those ‘50s banners above our head here at the Lions’ practice field. Considering his home was in the middle of the island, Sewell was lucky. They all climbed the hill and waited out the storm. The water couldn’t reach them.

That second tsunami? That’s the one that really caught them off guard.

Sewell can still see the mass panic.

He grew up in a large family and everyone in the moment, he recalls, “was scattered.” Penei was with his little brother (Noah), his older sister (Gabriella) and his mother. His two older brothers, Nephi and Gabe Jr. were with his father. Penei’s bolted to the top of that hill by their home and they had zero clue where the other three sought shelter. They could only sit in horror as the water rose… and rose. The sight of a tsunami is haunting. “You see the water kind of rise,” Sewell says. “You don’t see it coming in. You just see it rise.” Only after the fact did they find out Dad, Nephi and Gabe made it to their grandfather’s house at the top of the island.

The storm destroyed 30 percent of the island. All homes, churches, businesses along the edge of the island were wiped out so Penei and his four siblings chipped in to help others piece their lives back together. A couple of his classmates saw their homes completely demolished into ruins.

His home might’ve survived… but no. The Sewells weren’t living a life of luxury.

Their home was a “shack,” not a “house,” with all of one bedroom. And since they only used this bedroom as a closet for all of their clothes, all seven family members slept in the living room on seven mattresses. They weren’t exactly on futons, either. All Penei remembers is that whatever each person slept on was “soft.” That’s all that mattered. During hurricane season, his two older brothers would brandish a giant net over the metal rooftop and hold it down with boulders in the corners. Otherwise, those metal roof panels would serve as flying razor blades in those wicked winds.

The Sewell boys built the shack themselves. That roof had holes in it so, sometimes, water leaked right through.

“The life I have now? Compared to then?” Sewell says. “Night and day. It’s something I’ll never forget. Everything I have right now, I’m just spoiled.”

When it was time to cut the grass, no, he could not pop earbuds in, turn a key and peacefully listen to a podcast. Nor did he own a push mower. Or a weed whacker. His primary chore as a kid was to cut the grass with a machete. Seriously. The size of his grass to cut was the width of a football field and 40 yards long. Rocks were everywhere. He’d swing away… nonstop.

Here, he imitates the swinging motion.

“There’s a technique to it,” Sewell says. “Your wrist has to stay locked the whole time and you’re just swinging your shoulder. Then, you’re moving your feet. On the island, if you have a weed whacker, I guess you’re considered rich.”

He never complained. He enjoyed the labor. It was one hell of a workout.

Especially when he and his brothers had to round up bushels of bananas.

At the banana farm near their shack, they’d take turns tackling the trees. One tree particularly gave them trouble — none of the Sewell boys could get it down. And while a kid at age 7 to 10 throwing his body into trees repeatedly may sound unsafe, Sewell makes sure to add that banana trees actually have some cushion to them. They’re made of a “softer bamboo type of material,” he says. This sure beat all of the other chores he could’ve been doing, too. Others would clean dishes in the shower because nobody trusted Penei. Like any red-blooded male, he was apt to give dishes the ‘ol three-second splash of water and say, “We’re good!”

From this remote outpost, it did feel like he was detached from the rest of the world.

And yet, Sewell was quickly versed in all things American Football because his father, Gabriel, was a coach on the island. The moment he was old enough to even know the sport, Sewell fell in love. He’d set up cones at practices for the Marist Crusaders, run all over the place and yell at the players. “You have to run. Run!” he’d scream. Then, every time he headed to the beach was the absolute best time of his life. Penei and his three brothers would scavenge for a two-liter bottle, fill it with sand, a few rocks to add weight and use it as a football for a game of two-on-two.

“We’d go at it,” Sewell says, grinning. “Drilling, drilling, drilling! That’s what we loved to do. It was weird. I didn’t know I was going to love it like that. On my days off, I’d just go play football.”

At age 10, he begged Dad to let him play little league football. Gabriel thought he was too young the first year but unleashed Penei the next year, at age 11, against kids aged 14 and 15.

“And,” Penei adds, “they’d just kill me.”

One running back that’d play JUCO in the states — “Oh-tu-wah-lei,” he recalls — once flattened him like road kill when he tried filling the gap as a linebacker.

“I would get killed left and right,” he says. “There was this guy touching 350. Yes. 350, about 6-3 or 6-4. Just big. And he would obviously kill me. Even the little guys. The little guys who would run, they’d come down with their head and just smack you. Pads and everything. I was just getting killed.”

Seeking more opportunities for their kids, Gabe Sr. and Arlene moved the family to the states. To Utah. And when Penei started playing against his peers in the U.S., three words crossed his mind: “This is easy.” Everybody else was now looking at him the same way he looked at those 15-year-olds.

“Running around,” he says, “just smacking shit. Boom! Left and right. Running. So, it’s a testament to the island — everybody was tougher, everybody was bigger.”

There’s something to the Polynesian culture. Beyond that, Mom and Dad used to tell Penei that their people were born with “big bones.” Marinate this all with a heavy dose of raw motivation and Penei Sewell was a creature nobody at Desert Hills High School had seen before. Simply having 50 cents to buy a Mountain Dew or bag of chips from the vending machine filled him with joy and gratitude. He was grateful “for every little thing.”

Quickly, Sewell hit an insane growth spurt. He couldn’t stop eating. The memory of his first trip to a buffet is as clear as any collision on a football field. One Sunday, after church, the Sewells visited a Golden Corral and Penei swiftly devoured everything on his plate. He got dessert, too. Devoured that. And Dad chimed in.

“Son,” he said, “you’re going to get more, right?”

“No,” Penei replied, aghast. “I’d be stealing!”

“No, no, no, son. This is a buffet. People are allowed to keep going.”

“Really?”

That point forward? “It was over,” he says. Penei averaged three full plates per buffet visit. One plate would be devoted to steak. Next was the chicken. The chocolate fountain stood no chance.

He beefed up, put the football pads on and swiftly started sending kids to the hospital.

Granted, even Sewell feels bad about the hit that gave him instant street cred in the states. It occurred during a drill that’s probably outlawed by most high school teams now: “Sharks and Minnows.”

The first day of football practice, coaches picked two players as the “sharks.” They stood in the middle of the field. Everybody else was the minnows. All they had to do was sprint from one side of the field to the other — a distance of about 25 to 30 yards here. The sharks were permitted to seek any prey they desired. So when it was Sewell’s chance to be the shark, the choice was simple. He sought out the biggest, baddest dude on the team. The kid his father had been raving nonstop about leading up to this first practice. Blah, blah, blah. His Dad couldn’t stop bragging about this kid. “I want you,” Penei remembers thinking the second he laid eyes on him.

The whistle was blown and he approached this minnow furtively by shuffling toward him with his eyes looking elsewhere.

To fool him. To make him think he was teeing off on someone else. To set up this demolition.

And the second he got close enough, he booked it…

“Doosh! Nobody knew who I was. Boom! Smacked him. And everyone went ‘Oh my God!’ My coaches went, ‘OK, OK, OK.’ You can’t do that. I was like, ‘What do you mean? He’s got pads on! He’s got a helmet on!’ And he goes, ‘I know, I know. But you can’t do that.’”

Understandably so. The poor sap suffered a concussion and a sprained ankle. Sewell thinks he might’ve broke that ankle, too. He’s not sure. He never had the opportunity to follow up. A starter on the team, this kid didn’t play all season and that was both the first and last time Sewell ever saw him. He disappeared, and into ninth grade? Sewell remembers the kid attending a completely different high school. As if permanently spooked and scarred by Sewell, who was promptly banned from all future games of “Sharks and Minnows.”

Of course, it was hard to argue with the decision. Sewell was 6-3, 325 in eighth grade. Desert Hills needed to field a team.

Soon, he started turning this mass into muscle.

On to the University of Oregon, he allowed all of one sack on 1,376 career snaps and pass pro wasn’t even his greatest strength. Sewell loved the fact that he could run full speed and unleash anger as a run blocker. There’s no specific source of anger, rather this is all a product of living on the island up to age 11. He truly believes he wouldn’t be here — on this Lions O-Line — without his upbringing. He fell in love with football’s physicality.

“And whatever level up to what your violent intentions are? Mine is 100 percent. I’m going to actually put violence against you,” Sewell says. “It’s just in me. Because when I’m in-between the lines, and I see him lining up against me, I take it personal. I make problems that don’t even exist. He’s lining up against me and I’m like, ‘You should not be out here with me.’ Simple things like that. Taking it to a personal level.”

When he uses those words — you should not be here — Sewell treats this visitor like a defensive end. He stares at me in disgust. Such language was no doubt music to the ears of a GM (Brad Holmes) and a head coach (Dan Campbell) making their first selection together in 2021. At No. 7 overall, they couldn’t call Sewell fast enough.

Holmes informed Sewell he’d be the pick, then he handed the phone to Campbell.

“Big man!” Campbell said. “We are fired up, my friend. You’re going to change the culture for us, man. We’re going to build this thing around guys like you — do you hear me? … You come in and be just as nasty and as dirty as you’ve been and you’re going to help us turn this thing around. We’re going to be winners. You’re the building block.”

The Lions went 3-13-1 last season. Minor details.

Behind the scenes, Sewell was the living, breathing, bruising embodiment of everything Campbell was implementing for the long haul. In Game No. 1, Sewell took on San Francisco’s Joey Bosa. He suffered a high ankle sprain, played on and showed flashes of dominance. Sewell finished with the best PFF run blocking for any rookie tackle in the past 12 years. His mindset always flips on gameday, he adds, to letting it all out.

“Without giving a damn about my body.”

And for the Lions to even think about raising a new banner in this facility, it’ll take so many moments like this one. Like the time he went full “Sharks and Minnows” on Aaron Donald. Exactly as he did in eighth grade, Sewell needed to take on the baddest SOB on the field in Detroit’s 28-19 loss to the eventual champs. Midway through the second quarter, on the backside of a play, Sewell stood up the three-time DPOY and stayed firmly locked into Donald through the whistle.

Which didn’t sit well with Donald. Which prompted Donald, a known hellion, to grab Sewell by the facemask. All he remembers is Donald saying, “You can’t f--k with me.” Players from both sides intervened but, hell no, Sewell wasn’t going to let this slide. Two weeks removed from his 21st birthday, Sewell retaliated by grabbing Donald by his facemask. Milliseconds from swinging away, he gave the facemask a shove and restrained himself.

Position coach Hank Fraley warned his crew all about Donald. They knew he’d get hot. Sewell figured they were destined to clash after the whistle.

“Because,” he says, “I see red. See red.”

The only reason Sewell didn’t start throwing haymakers was those teammates he’d die for. Taking this skirmish one inch further would’ve been selfish. He didn’t want to hurt his team. “If I just see red,” he says, “and don’t even think?” Sewell lets that question hang in the air, to let our own imaginations run wild. Yes, Sewell needed Donald to know he was the real bully out here. Resumes be damned. And that’s why he views himself as the Rodman of this Lions posse. The power forward who’ll get “down and dirty.”

Sewell is both the maniac diving headfirst into the crowd for a loose ball and the clairvoyant dissecting blocking with the same brilliance Rodman does rebounding. Like Rodman masterfully tipping the ball to himself in the ruckus of the paint, the way Sewell blocks looks different. He’ll use a defensive rip move to roast his man. Or a cross-chop. From Malaeimi to Allen Park, he has honed the art of blocking in his own image.

Rodman had an incomparable “energy” and “mindset” about him every game. That’s how Sewell plans to attack this Lions O-Line.

The good news: He’s not alone.

The power of loss

Jonah Jackson calls himself the “mystery” of their group, which is funny because there doesn’t seem to be much mysterious about a human being who’s a mountain of a man in his own right at 6 foot 4, 311 pounds.

But that’s what happens when you hail from Media, Pa., when you’re a much less heralded prospect from high school to college to the pros. Media is a small town about 20 minutes from the Philadelphia Eagles’ stadium. Not quite an island in the Pacific. “Right off 96,” he says. “Exit 6 or 7.” After playing three seasons at Rutgers, Jackson transferred to Ohio State for one year and the previous Lions regime selected him in the third round (75th overall) of the 2020 draft.

Life experiences made him, too.

He’s built to smash fools.

“I’ve been through the ringer,” he says.

At the same age Sewell was taking on Donald and asserting himself as a young star, Jackson didn’t even know if football was for him. He sounds like a proud big brother thinking back to that Rams game. Donald loves to hook linemen by the facemask, he explains. That’s his way of bullying and belittling opponents. Five weeks later, he wasn’t even flagged for choking Packers guard Lucas Patrick. Nor did Patrick fight back. Usually, Donald gets away with his dirty antics.

“Not with five-eight,” Jackson says. “It’s that Polynesian Power. The crazy thing is he’s doing this at 21 years old. When I was 21 years old, I was applying to state trooper internships.”

That’s because Jackson had no clue football could even be his career. A redshirt junior at Rutgers then, he was only hoping an NFL team would one day invite him to a training camp.

His heart was broken, too.

His life could’ve taken a hard turn one of two directions.

This was right when his grandmother — “a second Mom” — tragically passed away. The loss shook him because Patricia Jackson, he explains, “was a boss.” With his own parents working so much, she’s described as a major driving force in Jonah’s life. Patricia essentially raised him from birth to 21. He knows he took everything from his grandma, too. Her sense of humor. Her cooking skills. Her dance moves. Maybe he’ll catch a touchdown one day like Decker and get a chance to show the world just how much rhythm he has — Patricia is to thank. She was a “gangster,” he assures, who listened to plenty of Lauryn Hill and Mobb Deep and one of his most vivid childhood memories is rocking out to Mariah Carey’s Christmas album with her.

When that “All I Want For Christmas” beat dropped, look out.

“A little shoulder work,” he explains, snapping his fingers and nodding his head. “A little… ‘uhh.’ She loved a little head movement with her snaps. She had some footwork before her strokes.”

About those strokes.

She miraculously survived seven of them in back-to-back succession. A heavy smoker for much of her life, Patricia lived a couple more years before getting cancer. The first chemo treatment didn’t work well and — as Jackson puts — the clock started ticking. They knew her health was deteriorating. And since his siblings were older with kids of their own, it was only Jonah with his grandmother inside of her hospital room when she passed.

While remaining hopeful, while holding out hope she’d wake up, he said his goodbyes.

She did not wake up. He was the last one in the room.

“It’s a scarring experience,” Jackson says. “But it makes you stronger. It was definitely a vulnerable moment. Just spewing out the last words you want to say to her. Getting those final words out. I’m at peace with it because I was there when she took her last breath.”

Jackson took some time off before heading back to school… but return he did. He finished his Rutgers career, headed to Ohio State, earned a starting spot on the ‘19 team that reached the college playoff and — all along — made a point to talk to his grandmother before every practice, every game.

To this day, in Year 3 with the Lions, he still does.

He tells his grandmother he loves her and that he’s playing “for her.”

“And she’s with me,” Jackson adds, “every step of the way.”

He cannot shake this visitor’s hand in a full vice because of the injured ring finger on his right hand. It’s heavily bandaged. Jackson missed Detroit’s win over Washington and won’t play Sunday against Minnesota. Yet this is why the Lions are so dangerous. They’ve been building such a powerhouse of an offensive line that — in an utterly shocking development — the term “next man up” will not make you puke all over the floor here. It’s real. The parts are becoming interchangeable. Despite losing the 6-foot-6, 328-pound Vaitai to IR and despite missing both Jackson and Ragnow the Lions are averaging 4.6 yards per carry before contact.

Special bonds are forged throughout the entire O-Line room. An unbreakable trust.

Many times, he and Decker don’t even say a word to each other. They diagnose the same intricacies at the line — in real time — and react. He calls it “telepathic.”

“Once you’re able to get to that level?” he says. “The sky’s the limit.”

He isn’t the only lineman up front thinking about a loved one every time he steps on the field.

The hulking center to his right on the line of scrimmage — Frank Ragnow, No. 77 — lost his father to a heart attack on Oct. 1, 2016 and has been incredibly open about it ever since. He makes no exception here. How did he deal with this? Honestly, he never did. He was numb. He was in the middle of his football season at the University of Arkansas when Mom made sure head coach Bret Bielema was with Frank when she delivered the news to him over the phone. Son went to the funeral that Thursday and then played No. 1-ranked Alabama on Saturday.

“I got into that football utopia and kept going,” Ragnow says. “I think that’s one thing that isn’t the smartest thing. That’s why I’m such a big advocate for grief awareness.”

His foundation, “Rags Remembered,” helps kids and families who suffer from sudden loss persevere through outdoor activities. His own father, Jon Ragnow, loved the outdoors. That’s why he also launched the YouTube Channel, “Grizzly Man Outdoors” — to chronicle his adventures doing what he and his Dad loved most. Fishing. Both parents used to tell him as a kid to go play outside all day and come back for dinner. That’s always been engrained in him. So, he’s passing it on. He’s fishing with kids who lose their loved ones.

This was his best friend. They’d enjoy marathon conversations after all football games.

“With him passing away,” Frank says, “it definitely motivated me to keep carrying out the dream.”

How Dad raised him is exactly how he’s trying to live. Above all, it’s about treating everyone in the building with love, with respect. He tries to connect with his teammates at a deeper level because these relationships are as “real” as it gets.

“Offensive line play, you really have to be one of the men in the arena to understand what we have to deal with day-in and day-out,” Ragnow says. “It’s the most physical position in all of sports. There are not many compliments. You don’t get talked about unless it’s in a negative light. Nobody understands what offensive line play really is. For us five to understand and to go through all of this together, and to embrace the suck together, whether it’s training camp or a hard practice or a 20-play drive when we’re grinding in two-minute, we embrace that suck together and it really brings us all so, so close.

“We know what each other’s going through and we embrace the heck out of each other.”

Because we tend to forget how very not normal it is for a 300-pound human to smash into another 300-pounder roughly 60 times a game. Nobody is neurologically wired to think this is OK. “And a lot of the times,” Ragnow adds, “you’re stepping backwards, as this 300-pound freak show is running full speed into you.” If a defensive lineman beats you once, that one play is what loops on the highlight reel all week. And you’re chop liver. Nobody cares if the other 59 plays were perfect. So while playing on the offensive line is physically demanding, the mental demands weigh heaviest.

Dan Campbell gets it. That’s why he made a point to congratulate Dan Skipper in the locker room after Detroit’s first win this season. Skipper had just started his first football game in six years. One of the emotional cuts on Hard Knocks, he’s never even made an initial 53-man roster. Chants of “Skip! Skip! Skip!” broke out from players in what was clearly yet another small moment toward this becoming a totally different Detroit Lions team.

That’s the resilience the coaches want coursing through the veins of everyone.

On the surface, it may seem like Campbell is the polar opposite of Vikings coach Kevin O’Connell. Whereas Campbell speaks as if he’s about to ball up a fist and drive a hard right directly into a brick wall, O’Connell carries himself with the calmness of a librarian. In truth, both are rebuilding their teams in similar fashion. Like the Vikings’ coach, Campbell values the psychology of his entire team.

He wants his guys to sincerely love each other. He wants mental fortitude.

“You’ve got to be resilient,” Ragnow says. “The guys who aren’t, they get faded out of the league or faded out of college. It’s difficult. I don’t think it’s anything you ever master because we’re all humans. You’ve got to be as tough as you can and understand you’ve got guys who are going through the same thing.”

That’s where this offensive line’s conscience steps in.

The one whose body is a tapestry of tattoos and whose passion sets the tone for everyone.

The protector

Adjacent to the team’s locker room, inside a quiet office, his voice is delicate. Calm. Comforting. No, Taylor Decker never endured such scarring trauma. He can’t relate to the tragedy and loss so many teammates experienced. But ask him to identify his singular source of motivation and he offers a warning: This will make him emotional.

He thinks of his parents. He thinks of his four older siblings.

“You see a lot of guys who come from backgrounds where maybe their Dad wasn’t there. Maybe their Mom wasn’t there.”

With that, his eyes well with tears. His voice skips a beat. The 6-foot-7, 320-pound left tackle who absolutely looks like someone who could’ve given those late 80s Pistons five hard fouls in five minutes clears his throat to compose himself.

“And I was super, super fortunate that my Dad and Mom were at everything,” he says. “My siblings were at everything. My brother Justin — he’s my best friend, he played left tackle, he was No. 68. I wanted to be like him. And then when I started getting some success with football, it was literally like, ‘I just want to make my parents proud.’ That’s it. Because they afforded me every opportunity to be successful. I would be an asshole to not do everything I can to maximize that because there’s a bunch of guys in that locker room who didn’t have that and they’re here still. I literally have the family name on the back of my jersey. I’ve got brothers, sisters, nieces and nephews, a lot of people watching me where literally all they want to do is be proud of their brother, their son, their brother, their uncle.”

He’s about to become the father next month. When his baby girl enters the world, Decker is certain these emotions inside of him will ramp up “tenfold.”

No player can relate to the dire need for change more than this 16th overall pick of the 2016 draft. Decker is the longest-tenured player on the entire team. He’s been here for Caldwell, Patricia and Campbell. He knows what NFL misery looks like.

That misery, however, only sharpened his outlook on life.

“We’ve had some shit seasons here,” Decker says. “But, man, I have a f--king great life. Why am I going to come into the building and be all ‘Woe is me. Life sucks.’ Which, guys can get like that. I’ve gotten like that before. But you just put that into perspective with what you’re fortunate to have.”

He admits it has often felt like the world is caving in around here. Losing does that. But then he poses a simple question to himself daily — What are you fortunate for? — and takes a deep breath. He hears what other players are going through in their day-to-day life. “Without fail every year,” he says, “we’ll have guys who say, ‘My brother got shot. This person got killed. My grandma just passed away who raised me.’” And he does everything in his power to stay upbeat and spread his positivity through the entire team.

Naturally, this offensive line takes his lead.

The best way to understand Decker’s presence here in Allen Park is to tour those tats. Nothing but ink cover his arms, chest, back, quad, calf and… fingers? Yes, those paws latching onto the NFL’s best pass rushers look more like a sensory-overload kids show on Netflix. For a while, Decker only got tattoos that carried a deep personal meaning to him. Not anymore. On these fingers, you’ll see totem poles, a cowboy boot, a stick of dynamite, a sword, an old-school football helmet, lightning in a bottle.

Decker was an animal science major in college. His love of animals is more of a life passion. When Campbell said he’d like a real baby lion to hang out at the team’s facility, Decker was probably all in. On his chest is a lion to honor his late grandmother — she had a statue of a lion with a headdress on it in her house — and an enraged gorilla inked near his left elbow is ripe with symbolism. Yes, this particular gorilla is blue in the face… with yellow teeth… and a scowl that suggests it’ll tear apart its prey to nothing but a pile of bones. But to Decker, the gorilla also epitomizes loyalty and control and being a protector.

That’s his role: “To take care of your own,” he says. When running back Craig Reynolds arrived, Decker didn’t even know his name. He had no clue this was an undrafted kid from Division-II Kutztown already discarded by the Redskins, Falcons and Jaguars. Decker loved how Reynolds ran like his life depended on it and told himself that he needed to lay it on the line for a guy like this. A feeling that’s harnessed and used for good with all of the Lions’ skill players: De’Andre Swift, Jamaal Williams, Jared Goff, etc.

“You want to do your best for them,” Decker adds, “because that’s more powerful than trying to do your best for yourself.”

The Lions skew young — very young — on purpose. Holmes and Campbell cut a slew of vets loose upon taking over and make it clear publicly that they weren’t afraid to play rookies. Into Year 2 of the rebuild, somehow, this roster got even younger. Per Philly Voice, Detroit entered the 2022 season with the second-youngest team in the league at an average age of 25.1 years. Spotrac’s math had the Lions as the youngest. Decker puts it on himself to make sure all of these young guys play with confidence because he knows confidence is an ultra-fragile thing. Players can lose it, and never get it back.

Speaking positively 24/7 helps. So does changing your habits. Whenever a daunting matchup awaits him on the QB’s blind side, Decker doesn’t watch a highlight reel of that player. He isn’t ripping through clips of Za’Darius Smith eating tackles alive in preparation of Detroit’s Week 3 game against the Vikings. Early in his career, he’d too often build up an edge rusher as some sort of boogeyman. Not anymore. He instead watches clips of a pass rusher getting manhandled at the line of scrimmage to instill positive reinforcement. He instead focuses on what he does best — not the pass rusher.

He's gotten teammates to do the same thing in their film prep. Nobody’s afraid around here.

Hell yes, he loved seeing the rookie get right into Donald’s grill last season.

“If you don’t try to get after them,” Decker says, “they smell blood in the water. The way to play against those guys is to not shy away, and to not be unsure about yourself. They might get you. You might have a bad play and they might have a TFL. You might give up a sack. But the mindset going into that can’t be, ‘I’m on the defensive, I’m being passive.’ Especially on the line. You go out there and you do what you’re good at, and you’re confident in that and you’ll be fine. You’ll be fine. You don’t want to go out there defensively guessing, ‘Oh, what if this happens?’ No. You studied the tape. You made your pass rush report. You know what this guy does. Go out there and do it.”

Around his wrist are the tatted words, “For those I love, I shall sacrifice.”

And on the inside of one arm, he has tattoos honoring his brothers who served in the Marine Corps and Navy.

Go down this road and his tears make even more sense.

Both of his brothers — Adam and Justin — served tours overseas. Adam spent time with the Marine Corps infantry in both Iraq and Afghanistan, while Justin did two tours with the Navy. One was in the South China Sea. Taylor has always been closest with Justin. “Super, super close,” he emphasizes. After fighting all the time as kids, they became best friends into high school since they’re only three years apart.

Meanwhile, Adam suffers from PTSD to this day. What did he see overseas? Taylor has no clue. Taylor would never ask. That’s why he always gets choked up during “Hometown Hero” events during Lions games. It hits home.

“There are good days,” Decker says, “and bad days.”

Don’t let his size and tattoos fool you. Decker is a sensitive guy. Even as a kid, he admits he never wanted to hurt anybody on the football field — it took a while for him to unleash the violence we see today. He’s simply extremely family-oriented and extremely driven by a sense of accountability. That’s who he is to his emotional core. When the ball’s kicked off, he’s able to flip a switch within and wield all of these qualities for good on the offensive line. Because this isn’t any ordinary offensive line. Again, these Lions would “die” for each other.

The love up front is real. This is Decker’s other family. These relationships transcend sports.

Nobody’s more determined to put an end to the losing more than him and he’ll make sure everyone on the line feels his same energy.

Through a string of crushing losses in 2021, true, the Lions refused to quit. But they also lost 13 games. That’s why last week’s physical beatdown was so rewarding. Finally, all of the work paid off in the form of a blowout win. The Lions want to unapologetically maul opponents and offensive line coach Hank Fraley is the perfect extension of Campbell inside of the offensive line room. A former player himself, Fraley went undrafted out of Robert Morris in 2000 and found a way to stick for 11 seasons.

He doesn’t merely talk about sacrifice and grit. He lived it. He played on Eagles teams that reached the Super Bowl and Browns teams that fell flat on their face.

The reward, Fraley explains, isn’t a pat on the back. It’s running the ball in 4-minute mode when everyone in the damn stadium knows you’re going to run.

“Coming out of the huddle,” Fraley says, “and being able to walk up to the line of scrimmage. There’s nothing like having the chance to beat up on somebody and put their face in the mud and stomp on it while it’s still in the mud. That’s the mentality I want these guys to have. And you build it. And you change that culture.”

That’s what this Lions offensive line is doing. Opponents are left battered and beaten.

Now, it’s time to win.

When the front five comes together, it’s a beautifully belligerent sight.

Read Part II right here.

Catch up on our latest features right here: