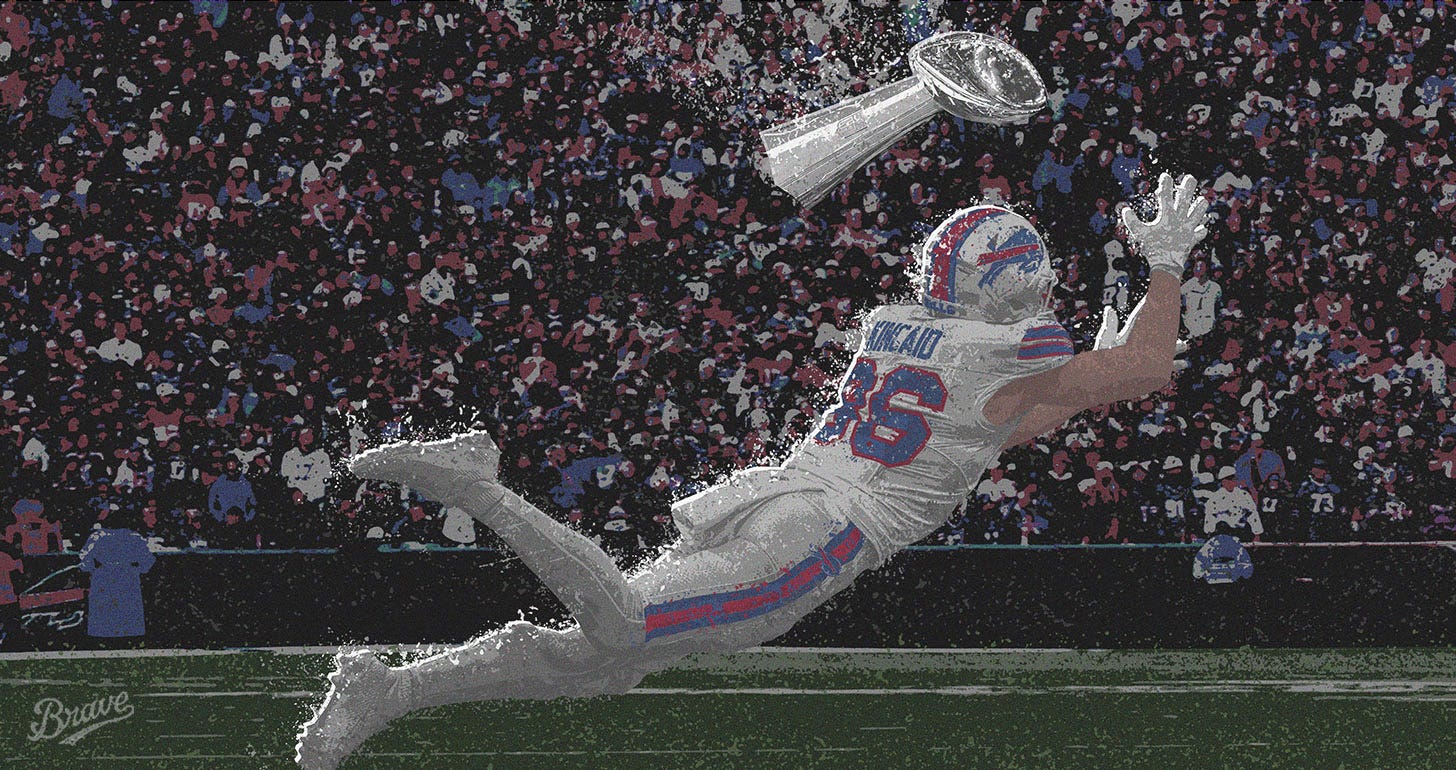

The Revenge of Dalton Kincaid

He dropped the crucial fourth and 5 with a Super Bowl ticket on the line. It was painful. But then? The Buffalo Bills tight end wiped those tears away. "That's the moment you want," he tells Go Long.

One football rains down from the Missouri sky like a gift from heaven.

Fourth and 5. Two minutes left. Forty-seven yard line. Arrowhead Stadium at a roaring fever pitch. All with a trip to Super Bowl LIX in New Orleans on the line? These are the six seconds we all simulated in the backyard with our Dads. Six seconds that feel like an eternity for the recipient. Dalton Kincaid is ready. The Buffalo Bills tight end sees the fluttering pigskin and reacts swiftly by slamming the brakes on his deep over route toward the sideline.

In one motion, Kincaid flips his body 180 degrees, dives horizontally and that golden ticket cruelly slips right through a narrow tunnel formed by his right bicep and forearm.

Difficult? Yes.

A catch NFL teams expect their first-round talent to make? Also, yes.

Six Chiefs players dance around his body in celebration. On all fours, all Kincaid can do is stare at that football, that gift bouncing downfield. It’s taunting him. He reaches both hands to his facemask in disbelief, ambles to his feet and then looks up at the videoboard. Once, twice, a third time, Kincaid essentially watches this sport rip his own heart out. He takes a seat on the bench and each breath is visible in the January chill. Eye black smears into his beard.

When the CBS broadcast zeroes in on Kincaid, he’s not speaking to a soul. He’s pale. Life appears to have left his body.

Reality isn’t far off.

“Numb,” says Kincaid. “Completely numb. Got a bunch of guys in the locker room you feel you let down. Coaches. Teammates. Staff. So many people pour in and are resources for us and our team. It’s a tough feeling.”

Go Long subscribers can access our 2025 NFL Season Preview features in full.

Today? Dalton Kincaid opens up at length on the drop, fighting back and what’s next.

The Bills lost, 32-29. Another legitimate shot at championship glory was vaporized by these grim-reaper Kansas City Chiefs. Now, he’ll talk about it. All of it. Here in Orchard Park, NY — months later — Kincaid relives the nightmare. How he remained disoriented as players all trudged into the visitor’s locker room. Naturally, teammates consoled a 25-year-old they viewed as a brother. This team is exceptionally close. But as his tears flowed, it wasn’t one heartfelt hug that snapped him out of this haze. No sermon of positivity, no texts from loved ones, nothing warm and fuzzy at all served as serotonin.

Kincaid required one kick in the ass from a teammate who wasn’t even in uniform that night.

The reason he’s standing here with his back straight, staring you in the eye, demanding the football with everything at stake again?

Micah Hyde.

The 34-year-old safety who’s played 175 career games was signed to the Bills’ practice squad one month prior for his presence alone. Hyde took one look at a quivering Kincaid and knew exactly what needed to be said minutes before reporters entered the room.

“Fucking own it,” Hyde told him. “You fucking suck up these tears. You look ‘em in the face and you own it.”

Go Long is your home for raw, real pro football.

We are completely powered by you.

Hyde could relate because Hyde’s been there. Eleven years prior, he read Colin Kaepernick’s eyes perfectly in the wild card round. That game was tied 20-20. Four minutes remained. He undercut a pass to Anquan Boldin and… dropped it. It was high, yet very catchable. The young DB would’ve coasted into the end zone at glacial Lambeau Field and been immortalized in Packers lore. That club was talented enough to win it all.

Instead? Those Packers, like these Bills, let too many title opportunities slip through their fingertips.

Emotions in this sport are most volatile those fragile moments after you believe you cost your team a title shot.

Hyde remembered how he felt that night.

Says Kincaid: “I don’t know if he knows how much I appreciated that moment from him.”

As the 2025 NFL season closes in, it’s no stretch to declare that the Bills’ Super Bowl hopes hinge on this playmaking tight end busting out as the team’s No. 1 receiving threat. The club’s two-word call to action — Everyone Eats — is borderline cultish at this point. Preached by coaches, echoed by players, it’s now stitched across that hat atop Allen’s head during press conferences. But if these postseason defeats teach the Bills anything, it’s that they’ll unequivocally need one alpha to emerge.

One fighter who’ll make the play in the clutch. The most likely candidate is Kincaid.

Year 2 was hell. Injuries to both knees zapped his athleticism: a torn PCL in one, a Morel-Lavallee lesion in the other. Not that anyone knew. Kincaid obviously didn’t want to publicize the details to defenders foaming at the mouth and — plainly — he has always believed that if he’s “breathing,” he should be playing. Fact is, the simple kinesiology of bending his knee was painful.

He struggled. His numbers took a hit. The KC play happened.

Those six seconds were potent enough to kill his career on the spot.

Instead? Hyde’s words set the tone.

Kincaid boarded the team charter back to Buffalo and immediately attacked the 2025 season with maximum ferocity. First, he refused to treat the three-hour footage as the cursed video tape from The Ring. Ignoring the AFC Championship — burying the horror deep in his subconscious — would’ve only delayed the inevitable. He needed to accept the truth the very next day. He met with both GM Brandon Beane, head coach Sean McDermott and accepted their sharp criticism. Both stressed the need to bulk up and to turn the page — fast.

Countless teammates reached out. The quarterback who gave him a shot at being a hero was a go-to lifeline. Dawson Knox, kin at this point, checked in regularly. Tyler Bass became an exceptional resource, too. Buffalo’s kicker faced the exact same level of backlash the previous season after slicing a 44-yard field goal vs. the Chiefs. His advice: “Delete everything.” Completely detach from social media. “Nothing anyone says on there is going to help you,” Bass told him.

Inside the team’s fieldhouse, we’re standing exactly where Knox issued a passionate defense of his friend the day after Buffalo’s defeat.

This football team genuinely feels like a family.

But as the sound of a JUGS machine whistles in the background, the last thing Kincaid wants to do is echo Knox. He refuses to use the injuries or the trapeze degree of difficulty as an excuse. Thirty minutes pass and all teammates clear out — a familiar sight. This past offseason, Kincaid spent more time inside this building than anyone on the roster. He never wants one play to consume his brain but he’s certain he figured out a way to use heartbreak for good the last five months.

“It definitely drives me,” he says. “It’s not something you want to completely use the whole time, but it’s definitely still there. You’re in the weight room and you get after it a little bit.”

All help from others inside this building was appreciated.

Dalton Kincaid realizes that sweet redemption ultimately boils down to one person and one person only.

Himself.

KO’d

You do not choose the tight end position.

The position chooses you.

It’s Darwinian. Only the mentally calloused survive. Ditka to Gonzalez to Kittle, the best of the very best possess a set of characteristics that naturally gravitate them toward the profession. As Tony Gonzalez bluntly put in our “Blood and Guts” chat a couple years back, playing tight end represents life itself because it “forces you to do shit you don’t want to do.” You’re guaranteed to come face-to-face with your deepest fears. All while feeling like a man without a home. Dallas Clark correctly labels the tight end the official “redheaded stepchild” of a roster. Linemen hate you because you step on their toes and need help in the run game. Receivers hate you because you steal targets. Those with just the right amalgam of altruism, athleticism, intelligence and savagery inevitably become an American Tight End.

You’re asked to do more than anyone in the huddle and, yes, you may decide your team’s championship fate.

Growing up in Las Vegas, Dalton Kincaid never dreamt of tight end glory. Football itself was an afterthought considering basketball was his first love. He agrees that how someone plays basketball tells you everything you need to know about that person. That’s why Kincaid likens his game to Shane Battier. He felt an intrinsic need to affect the game in every conceivable way. As a freshman, he was the point guard. By his senior year, a center. Kincaid even won an AAU title with future UCLA guard Tyger Campbell.

And like his forefathers at the position, an ability to seize every opportunity steered Kincaid right into the NFL.

As he transferred from Coronada High School to Faith Lutheran — to join those AAU buddies his senior year — Kincaid joked to one friend that he might play basketball and football. He wasn’t being too serious because he never played the latter in high school before. He merely saw the sport as a way to meet new people. But when that friend said something to his father, son says Clark Kincaid’s “eyes just blew up.” Soon, the sport became his ticket to collegiate athletics. The team’s star wide receiver broke his collarbone catching a touchdown — “a sick touchdown,” Kincaid adds — and he was thrust into a starting role. Faith Lutheran’s QB looked his way nonstop.

Kincaid, a zero-star prospect, walked onto the team at the University of San Diego and earned the opportunity to transfer to a Power 5 school.

Utah was interested. Sort of. Tight end coach Fred Whittingham Jr. obviously loved Kincaid’s receiving ability but the fact that the kid had no clue how to block concerned other coaches on staff. They didn’t have a dire need for a tight end, either. But one day while scouring that San Diego Toreo film, Whittingham made a discovery.

One game, Kincaid was thoroughly getting his ass kicked by a defender. Until, out of nowhere, he had enough. Kincaid was visibly sick and tired of getting embarrassed…and fought back.

“It flipped a switch,” Whittingham says, “and it looked like it kind of ticked him off. From that point forward in the game, his blocking really escalated.”

The coach brought this film to another coach as if clutching a winning lottery ticket. “Look at this!” he insisted. “He can do it. He just had to want to do it.”

That moment hinted at the bigger picture. If Kincaid puts his mind to anything, Whittingham realized, he’ll do it. Hell, Kincaid wasn’t fazed at all by the presence of two established sophomores in the tight end room: All-Pac 12 starter Brant Kuithe and future pro Cole Fotheringham. Which was strange. Whittingham was used to transfers seeking a guarantee that they’ll play Day 1. Most demand a smooth path toward playing time. Here was Kincaid quipping that he’s all for 13 personnel.

Deep inside, Kincaid knew that all he needed was a crack in the door. One chance.

Kuithe tore his ACL in 2022, he got his shot, he caught all 16 passes thrown his way vs. USC for 234 yards and a TD.

Just like that, Dalton Kincaid became the No. 1 tight end prospect in the NFL Draft.

“Every snap,” Kincaid says, “the quarterback’s eyes went straight to me.”

Easy to see why. Those two hands were his superpower. Whittingham only remembers Kincaid dropping two passes his entire collegiate career. Each one haunted him. Pissed him off beyond belief because — to his core — Kincaid embodied the Utes’ day-to-day doctrine: “No excuses.” Whittingham tells his tight ends nonstop that if the ball hits their hands, they’ve got to catch it.

Says Whittingham: “He truly is a guy that came in with that mentality: ‘If that ball is anywhere in my vicinity, I can catch it. I’m going to catch it.’ And if he doesn’t — which is very rare — it really motivates him to make up for it.”

The arrow continued to point up — only up — for the kid who picked up the sport out of curiosity.

The Bills made Kincaid the 25th overall pick in the 2023 draft. He caught more passes than any tight end in franchise history, 73 for 673 yards and two touchdowns. He became the odds-on No. 1 target on a Super Bowl contender when Stefon Diggs was jettisoned to the Houston Texans. And in a Week 10 game at Indianapolis, Kincaid found himself wide, wide, wide open down the right sideline. In a cruel twist of fate, the league’s MVP badly overthrew his tight end.

Kincaid dove, landed awkwardly and promptly became a shell of himself. He tore the PCL in his left knee and the Morel-Lavallée lesion in his right knee led to a case of bursitis. He still Googles that funky name.

Essentially, the skin underneath the knee filled up with fluid. It took weeks to figure out what was wrong.

“Fluid blew up in my knee to the point where there was always this pressure,” Kincaid explains. “Bending the knees wasn’t the greatest thing. It was something I’d never dealt with, so you’re trying to navigate it. Football to me is if I can walk, I’m going to play as long as I can. If I’m breathing, I am going to play football.”

He’s not sure which knee hurt worse. Whenever one felt OK, the other throbbed. Adrenaline helped mask the pain to the point where he could suit up, but he still felt too rigid. And come Monday? He felt like a creaky old man.

Most pros would’ve shut it down for a month minimum to let a PCL heal and/or solve the mystery in the other knee. Kincaid sat out only three games, and played right through the AFC title loss. No surgery was required in the offseason — only time. There was no need to read between the lines at his bosses’ season-wrap pressers. Both GM and head coach said at the podium that Kincaid needed to increase his play strength to withstand the rigors of the NFL.

All while death threats trickled in.

This, ladies ‘n gents, is where NFL careers tend to deteriorate for good.

Perhaps, the body recovers. But not the mind. That fourth-and-5 snapshot takes up residency in the brain, serving as a source of psychological torture.

Flip through the history pages at this position, however, and Kincaid is not alone. Many of the best ever crash-landed to rock bottom early in their careers and found a way to climb out.

Tony Gonzalez led the NFL with a ridiculously high 16 drops in his second season. Overcome with depression, the young Chiefs tight end started locking himself in his bedroom to sob and numb the pain with endless Jack and Cokes. He once described this to me as a state of total “self-loathing.” Added Gonzalez: “Such a bad place to be, but such a good place, too — if you can get through it.” That’s because the pain forced Gonzalez to look in the mirror. He thought he was doing everything the coaches told him to do. But that was the problem. It was time to ask himself: “What else can I do?” Gonzalez started going to practice early to catch 100 balls in rapid-fire succession, a daily routine that stuck for the rest of his career. All Gonzalez did next was make the Pro Bowl in 14 of 15 seasons and forever change the position.

Ten games into his rookie season, Dallas Clark was drilled in the knee by Ty Law, helicoptered through the air and completed shattered his ankle. All in the wake of clawing his way onto the team at the University of Iowa as a real-life Rudy. All in the wake up of his mother dying in his arms. No sweat. Clark became the variable that elevated those Peyton Manning-piloted Colts to historic proportions. (Just ask, Peyton.)

Hey, remember the time a young Rob Gronkowski — fresh out of a walking boot — dove for a Hail Mary in the Super Bowl and missed the deflection by inches? A few hours later, he became the story of the game for all the wrong reasons. At a postgame party in Indianapolis, he party-rocked with LMFAO and his brothers at 2:30 a.m. The sight of “Gronk” tearing up the dance floor, shirt off, mortified everyone. Shouldn’t the Patriots tight end be sulking in defeat? Backlash from former Patriots was swift. Rodney Harrison, for one, said Gronkowski would’ve “got his head rung” if he was present. All Gronk did next was continue to party his ass off, work even harder and cement his status as the greatest tight end in NFL history.

Long before launching “TE U,” George Kittle was a wreck in college. Everything seemed too militaristic to him and, mostly, he was crippled with sports anxiety. The fear of screwing up in practice was suffocating. A psychologist suggested drawing a red button on his wrist tape. That way, after each play, he could slam that button to “reset.” A simple tactic that created his self-described “fuck-it mentality” today. Now? He’s the modern-day standard at the position, the truest reflection of the sport itself. “Football is a violent sport,” Kittle said in reflection. “You need to be violent to play it. There are violent things that need to happen for you to move the football down the field.”

Venture 6 ½ decades back to the blueprint: Mike Ditka. All these years later, “Iron Mike” knows how close he was to dying. The Chicago Bears traded him to the Philadelphia Eagles and Ditka grew dangerously depressed. He’d drink practically every night and wake up in “strange places” with zero clue how he got there. His hangover the next day was so severe that Ditka couldn’t comprehend what was real and what wasn’t. When that second Philly season ended, Ditka got into a car and drove through a blizzard back to Chicago. “I was going to quit,” Ditka told me. Three days later? Tom Landry called to resurrect his career and save his life. He looked inward.

With his blue eyes, warm smile, flowing locks and instant kindness to a complete stranger, the Bills tight end here off Abbott Road appears gentle as a character on Sesame Street. Not quite Jeremy Shockey at a bar in South Beach smacking my shoulder to illustrate a point. It’s fair to wonder how someone so freakin’ nice handles something so freakin’ harrowing on a football field. Gonzalez was his favorite player growing up. As I share his Year 2 spiral — the drops, the drinking — Kincaid nods his head and brings up Mark Andrews’ dropped two-point play the week prior.

“You feel for him,” Kincaid says, “then it happens to you, and you’re like, ‘Fuck.’”

Yet, look closely and you’ll see a Ditka-like edge.

Kincaid isn’t exaggerating about staying on the field by any means necessary. Back at Utah, in the final regular season game, he somehow hauled in a twisting 29-yard touchdown grab in the back of the end zone between a pair of Colorado DBs… and crashed. Hard. Trainers put him through some X-rays and said he’d be good to go in the Pac-12 Championship Game. He played in his team’s blowout win over Caleb Williams’ Trojans but then a CAT scan revealed Kincaid did so with cracks in his vertebrae.

Even then, Kincaid wanted to play in the Rose Bowl. He didn’t care about his draft stock.

Utah needed to protect Kincaid against himself.

Whittingham has no doubt his former tight end will fight back this season.

“He is as mentally tough as they come,” Whittingham says. “There are guys that put on an air of ‘mental toughness’ and then there are guys that just are so tough, they know they’re going to do it. His will overcomes whatever ailments, whatever setbacks, whatever’s going on. He’s going to step up and perform. And I think it's a personal standard, but it's also a commitment to the team. He wants to win. If the Bills could make it to the Super Bowl and win the Super Bowl and he contributed to that, I don't think he’d give it a damn about how many catches he had.”

Given a mulligan, he’d play through the injuries again. He had no issues with his bosses’ candor, either. Kincaid calls it all “constructive criticism,” and insists that he wants to get stronger just as much as they want him to.

This offseason, he got in touch with who he’s always been as a person.

A man who lives by four words: Show up every day.

“You make the decision every day if you want to be there or not,” he says. “That’s what’s allowed me to succeed in life: going to practice as a kid and showing up every single day. Showing up to all the games. Always being there. Then, my competitiveness. That’s one of my biggest strengths — I love to compete and want to win every single thing.”

He knew his NFL career was bound to speed one of two very different directions.

So, Kincaid took Hyde’s advice.

He chose to “fucking own it.”

The Response

Drop a pass of this magnitude and it is human nature to pretend like the play never happened. Retreat to a beach far away from Orchard Park, NY. Reach for the bottle like so many tight ends before you, and effectively double-down on that “numb” feeling.

A great escape would’ve been understandable. This is the nation’s most violent team sport.

Instead, Dalton Kincaid chose to stay in Western New York precisely when every WNY’er asks themselves “Why do I live here?” — the snow, the cold, the taxes, the misery linger through the months of February, March, April. It was frigid. It was lonely. His only roommate was his dog. But Kincaid also knew that this was the best way for him to fight back — by quite literally showing up every day. When offensive coordinator Joe Brady said Kincaid lived at the facility, he was not offering standard OTA BS hype.

Outside of a few weekend trips, Kincaid stayed right here. Many days, the only people you’d see were the team’s head of strength and conditioning Will Greenberg, director of sports performance Joe Collins, physical therapist Joe Micca… and Kincaid. His parents flew in from Vegas to keep him company — that helped. But Kincaid’s life, for months, consisted mostly of lifting weights, lifting more weights, the sauna, the cold tub, agility work and the occasional trip to the Eternal Flame at Chestnut Ridge Park or Knox Farm State Park with his dog.

He'd toss the Frisbee to his goldendoodle right inside the fieldhouse, too.

New faces popped in and out. Kincaid was the constant.

Initially, it was odd to hear the Bills’ brain trust so emphatically state that Kincaid must beef up. Wasn’t this the dynamic weapon Beane painted as a “Cole Beasley”-like weapon shortly after the pick? Since inception, the Bills have been TE-challenged. Asking Kincaid to transform into some ’95-style meathead in the modern game felt like an asinine regression. When I bring this point up to Kincaid, he assures that all parties involved threaded a needle.

He wasn’t bench-pressing in an Affliction t-shirt to System of a Down at full volume. He still has a neck.

Greenberg, the maestro central to this all, knew Kincaid’s ability to cut and bend and run distinguish him from his peers, and incorporated exercises that accentuated such athleticism.

At no point did Kincaid feel like he was stiffening into a fossil.

At no point did he think Beane and McDermott ever wanted him to become a 260-pound, in-line blocker. They talked constantly.

Yet, Kincaid also calls his muscle gain “significant.” His goal is to play at a solid 6-foot-4, 245 pounds. Specifically, this season, Kincaid will keep hammering away at those dumbbells through the regular season, a lesson he’s taking from veteran wideout Mack Hollins. The deeper the Bills got into the season — November to December to January — the more Hollins attacked the weight room, and it worked. He stayed healthy and even earned another NFL contract into Year 9 of a journeyman career.

Too many players think they’ll hurt themselves lifting in the middle of the season. Kincaid saw firsthand that the opposite is true. It actually hardens you.

All encouraging.

But honestly? Mental rejuvenation matters more than anything physical. He took Bass’ advice to heart and deleted social media off his phone. (“Everyone,” the tight end says, “is pretty safe behind the screen.”) Instead of caring what tens of thousands of scrolling zombies think on an app, Kincaid leaned hard into his belief that you become the five people you spend the most time with, a theory popularized by motivational speaker Jim Rohn. In addition to family and friends, he spent more time sitting down with “Dr. Dez,” team psychologist Desaree Festa.

Give McDermott credit. Over his nine years, the Bills coach has tried to fill his building with all possible resources for players. And considering there was hardly any traffic in here, Kincaid had these resources to himself. He spoke to everyone he could.

The person who helped him most was the teammate he was drafted to replace. When Beane called Kincaid to welcome him aboard, the Kincaid family went nuts. Roger Goodell made it official. The Bills employee who should’ve been pissed off most was Dawson Knox. That night, his role in the offense was guaranteed to diminish, and it has. The vet’s reception total fell from 49 (in 2021) and 48 (in 2022) to 22 in each of the last two seasons. It hasn’t mattered. These two only grow closer. And closer. To the point of Knox championing Kincaid as a reason the Bills were even in the playoffs. The morning after the Chiefs defeat, Knox vehemently defended his friend and vowed to laugh in Kincaid’s face if he tries to shoulder the loss.

“I got so lucky,” Kincaid says. “You hear stories of guys coming into the league and they’re stuck around this guy or that guy and the vets are treating you bad. Dawson is a mentor. He’s someone I look up to — not even in football. But in life. That’s somebody that I want to be like.

“He’s a big bro. It’s really organic and natural.”

Kincaid pauses.

“Yeah, he’s the man.”

His perspective is powerful.

Kincaid dropped a pass in a football game. Knox tragically lost his brother. On Aug. 17, 2022, Luke Knox passed away. Mentor has opened up these scars to mentee several times. During an OTA speech this spring, Knox then shared his personal heartbreak to the entire Bills team. All players, all coaches, 100+ listened to each word. Knox was as vulnerable as anyone has ever seen him.

“He knows real grief and you respect him,” Kincaid says. “I can’t say enough good things about him and the person he’s been.”

His body is strong.

His mind is stronger.

First thing’s first in training camp: Kincaid must slay his demons on the Catan board.

His quarterback’s life is so perfect that Kincaid hates giving Allen credit for something near and dear to the spirit of this team. But, yes. The most stunning win he’s ever experienced playing this game came courtesy of his MVP quarterback with the Hollywood starlet wife and the $330 million contract. For those familiar with Settlers of Catan, Kincaid says Allen managed to score all of his victory points in two cities without building a single road.

Back to his days at University of San Diego, Kincaid has never seen a player pull off this move.

“Of course it’s Josh,” he groans.

Quarterback and tight end exist on the same competitive wavelength off the field.

Now, the two must bring this same energy to nut-cutting time on Sundays. There’s no denying the general effectiveness of Buffalo’s yeoman approach. The collective is strong. I’m with Brandon Beane on the construction of this roster — it’s on the defense to deliver — but one of these pass catchers must ascend for the Bills to reach the Super Bowl dais in Santa Clara, Calif. After the AFC Championship loss, Allen said himself that “it’s not the X’s and O’s. It’s the Jimmies and Joes.”

Once Kincaid asserts himself as the undisputed Catan champ inside the dorms at St. John Fisher College, it’s time to earn Allen’s trust as the undisputed go-to guy.

He is the “Jimmie” best-equipped to deliver a Lombardi Trophy to this trophy-starved city.

Back at Utah, on third and long, everyone knew where the ball was going. Linebackers dinged him off the line. Extra defensive backs tilted his way. “And he thrived on that,” Whittingham adds. “He wanted to be The Guy because there’s a lot of self-belief that he’s going to get it done.” Usually, college coaches are overly cautious when it comes to setting expectations because they know verbalizing the name of an All-Pro creates headlines, pressure. Not Whittingham. When asked what everyone should expect to see in 2025 and beyond, he cites Kittle as a comp.

A supercharged Kittle.

“He has better ball skills than Kittle,” Whittingham says. “And what I saw him do with his run after catch in college was Kittle-esque. I think he wants to block like Kittle, too. I know that’s not why they drafted him — to block guys — but I love to see him do it because he takes pride in it.”

Those newfound veins snaking up his forearms will help in this department. When I ask Kincaid who he envisions being this season, it’s a player who moves without pain, gains confidence and “plays free with the reigning MVP.” This whole everyone eats philosophy could corner the team’s back-to-back top draft picks into a no-win situation. The Bills insist they want more production out of both Kincaid and Keon Coleman, but that also requires more targets. Kincaid isn’t fretting how touches are disseminated, claiming everyone on offense has bought in.

If he’s playing on two good knees, he fully expects to create separation that consistently catches the eye of Allen.

“Winning games — that’s all I really care about,” Kincaid says. “Going out there and winning a Super Bowl. That’s all I want.”

The trek is never adversity-free. This league has the rare ability to morph rational humans into jackals. One split-second mistake, and in comes the vitriol. The threats. Goodell and the owners slipping into the bedsheets with gambling companies certainly does help the postgame discourse. Even after going dark, there was no way for Kincaid to completely ignore it all. What usually hurts players most in the wake of such a professional blunder is the NFL’s dehumanizing effect. Who they are as a person gets lost completely.

Who’s Kincaid? A lowkey local who enjoys walking his goldendoodle through Orchard Park some days, while heading down the Southern Tier to go bow fishing at night. He fits his boat with lights and shoots carp with a bow and arrow. Who’s Kincaid? Someone who prioritizes others before himself. That breakout senior year, Whittingham remembers the tight end fetching bottles of water for the scout team. After the KC heartbreaker, the coach sent him a text: There’s one guy I’d want 100 times out of 100 on that and that’s you. When Kincaid flew back to the University of Utah to see some friends and do Pilates with a woman he’s worked with in the past, he made a point to see Whittingham and deliver a signed jersey with a personalized inscription.

Nationally, in a blink, Dalton Kincaid became known for one mistake. That may seem unfair. However, the beauty of pro football is that this all can swing the other direction with one play. Triumph under that same championship stress and not only is your football record expunged — you’re lionized. A conquering hero. So, why hide? Damn right, he’d stay right here all offseason. He knows reaching the Super Bowl will require slaying that fourth-and-5 demon.

He craves the exact same scenario this January. Perhaps defensive coordinator Steve Spagnuolo again unleashes a foreign pressure that forces Allen to heave a prayer. He’ll track the ball, plant, redirect and dive.

There’s nobody else in the fieldhouse now. Kincaid stares off toward the far end zone, as if recreating a second chance.

“That’s the moment you want,” he says. “One hundred percent. You want the ball to come to you in those moments.”

This time? He catches the ball. Buffalo advances. And that night, he fully expects to hear from a familiar voice. Even if, you know, Micah Hyde is officially retired.

“I feel like he’ll always be around.”

I literally have thought to myself so many times this offseason, “man I wonder what Kincaid went through after that drop”. This is a needed piece. Awesome work man. Also I promised myself I wouldn’t draft Kincaid in fantasy… that might’ve just went out the window

A thorough breakdown of the play in question in case anyone wants to re-visit Spags fooling Josh, Josh wriggling out of it to make a 40 yard throw with two dudes in his face, DK86 misreading the pass, DK86 correcting himself and having it go through his hands....

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K212ksvHIVI