'I’m still alive:' The Zay Jones story

He dodged death. He battled depression. He's stronger than ever. But, how? The Jacksonville Jaguars wide receiver tells all to Go Long.

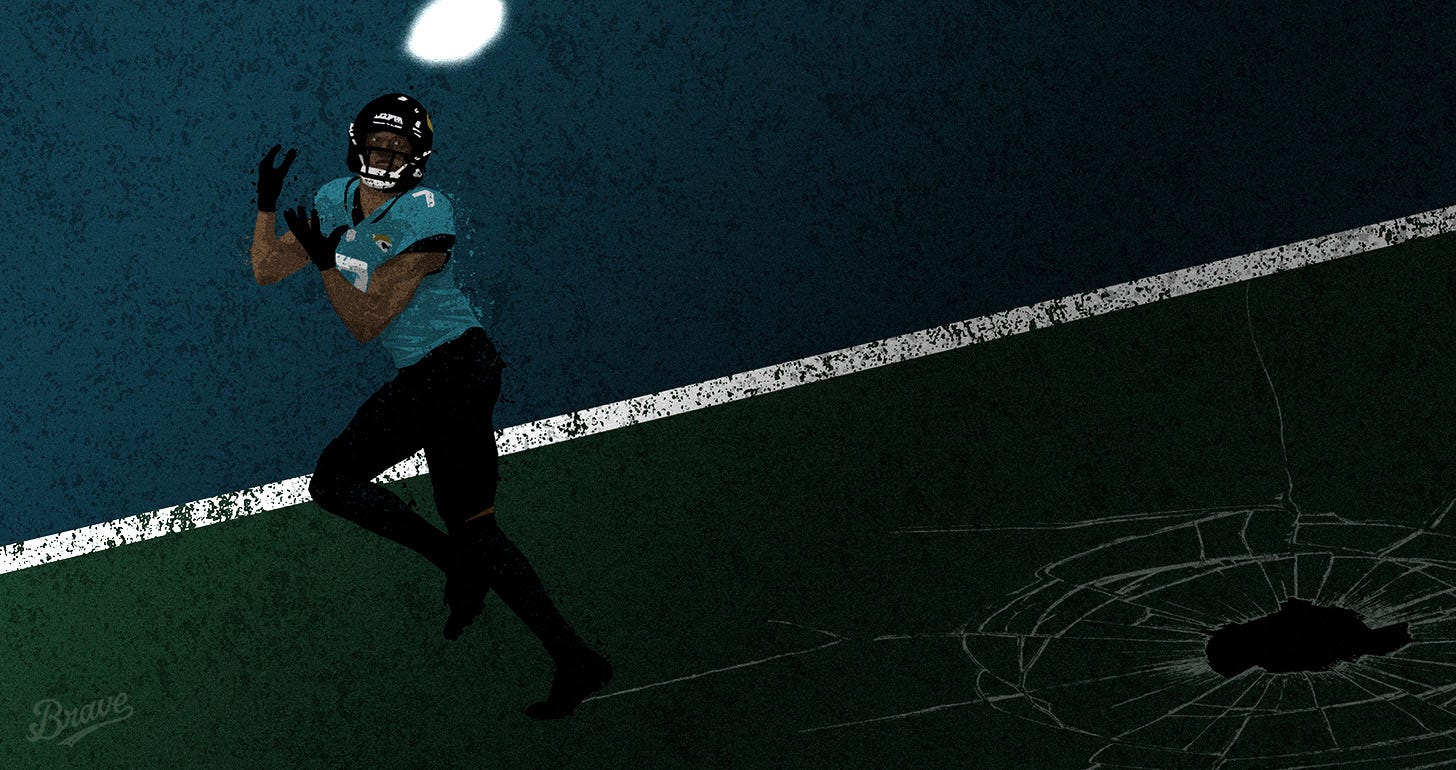

JACKSONVILLE, Fla. — Zay Jones shouldn’t be lounging here at Jaguars HQ. He knows that much. He knows he tried to hurl himself through the window of a Los Angeles condo 30 floors high.

The events of March 19, 2018 horrified the sports world. We all remember the 1-minute, 49-second TMZ footage. First, Zay storms naked through a hallway and declares: “I want to fight for Jesus.” Repeatedly. His brother, Cayleb, tries to talk sense into him. There’s a tussle. Zay sprints off to the frantic scream of Cayleb’s girlfriend. The next clip reveals the aftermath. You see swaths of blood all over the walls and floor. An accompanying photo is equally haunting. It’s the shattered window and not only is the window spiderwebbed — there’s a sizeable hole. About the size of a head and a half.

If not for Cayleb hanging on for dear life until authorities arrived, Zay forces his way through that hole and falls to his death.

Immediately bringing this night up is akin to lighting the table between us on fire. But an hour in, it’s time and Jones doesn’t hide. He begins by saying he cannot recognize the man in that video. I ask if he was on drugs.

“That night was such a mysterious night for me,” Jones says. “First, I was with some people I shouldn’t have been with. I never wanted to completely know what was in my system. I left it for what it was. I could only imagine. But I didn’t really want to know.”

What Jones saw that night was not reality. He didn’t see a condo, a hallway, a window. He saw… something else. Jones politely declines to go down that road.

Thankfully, his brother intervened.

“That night could’ve ended my life,” Jones says. “I’m grateful for another opportunity at life. I’m grateful to play this game. I’m grateful to be breathing and living and talking. Even to you. From the lens of seeing the brevity of life and how quickly things can change — they can go.

“If this is a reason why I’m still here, to go to this place, I want to make the most of it.”

Five years later, he’s here. He’s a wide receiver for the Jacksonville Jaguars fueling real AFC title dreams. Jones was identified as a player — no, a person — to lead a young team. In 2022, he was the clutch playmaker Trevor Lawrence turned to when the season was on the line. It’s also impossible to believe the person in that viral clip is the same one sitting right here with the frizzy hair, dark brown eyes, ultra-compassionate dialect and ultra-neighborly manners.

He’s the life of every room. Including this one. His hands never stop moving in conversation.

His impersonations are uncanny. His McVay, his Gruden, his Carr.

He’s at peace. Jones has learned to free himself of the sport’s stressors.

“If I catch a touchdown pass to win a game or if I drop a touchdown pass — and I’ve been on both sides of it — the Lord still loves me,” says Jones. “I’m still alive. I’m still here. I can always get back up on my feet.”

Finally, he believes it’s time to open up. For two hours, Jones takes Go Long readers through the rise-fall-rise arc of his life.

Emphasis on that fall, because nobody had a clue how much he was struggling early in his pro career. The Buffalo Bills’ 2017 second-round pick spent many nights in tears. After his dalliance with death, the world then perceived him to be something he was not. He heard everyone calling him a “meth head.” A “crack head.” A disgrace. He was eventually traded. And that’s why Zay Jones matters. In a society where depression rates only soar, he did not vanish forever. He navigated out of his abyss. Somehow. And if someone who fought like a banshee to manually eject himself from that L.A. window found a way to reach such bliss, there’s zero reason any of us should wallow in pity. Over anything.

Zay Jones transcends football.

The happiest man in football clasps his fingers over one knee and leans back.

Upon unclasping those fingers to reposition in his seat, one sight is chilling. Where many peers have a standard ACL scar, he’s got a pattern that resembles the spastic strokes of a paint brush. Suddenly, Jones starts pointing to areas all over his body.

His side. His head. His arm. His knee. Scars from that night are everywhere. He can never forget.

“I carry them with me,” Jones says. “Scars are proof that God heals.”

Go Long is your independent home for longform journalism in pro football. The aim, always, is to humanize the sport.

Get all profiles, all team deep dives, all columns by joining our community today:

‘A beautiful time’

Sleeping in was a sign of weakness, so sleeping in was not an option.

School didn’t start until 9 a.m., but Zay Jones needed to wake up at 6. Always.

His father, Robert Jones, believed the first key to success in life was starting your day before anyone else. To him, there was also intrinsic value to executing tasks you don’t necessarily enjoy. Many times, Dad would simply tell his boys to go outside and pick up branches. “See those leaves?” he’d add. “Put them all in trash bags.” Which never made sense to Cayleb, Zay and Levi. This was in the middle of a Dallas fall. More leaves would obviously drop and they’d be sent right back outside. Everyone else in the neighborhood was wisely waiting. All three would look at each other and ask, “Why are we doing this?”

Years later, they realized Dad was instilling a work ethic.

“It may be mundane and monotonous,” Zay says, “and we may not know all the reasons why but our father told us to. So, we’ll go do it. With a good attitude.”

No. 1, all kids were raised in a Christian household. Faith was everything. Robert made it clear he didn’t care if his boys “liked” him because they’d thank him one day. A message that wasn’t always received well because, Zay admits, kids think they know everything. He repeats Dad’s go-to lines.

Never leave your room without making your bed. (Messy sheets were sure to draw Dad’s wrath.)

Never talk back to your mother. (Mom homeschooled him up to sixth grade, teaching Zay everything from Spanish to Latin to math.)

I’m your father first. Not your friend. (The word “no” would be accepted.)

There was a very good reason for all of this. Robert Jones has a survival story of his own. The fact that Robert Jones is alive also makes little sense. This is a plot typically reserved for an HBO drama. Not nonfiction.

Robert’s infant life began with his own father shooting his own mother while she breastfed him. Baby Robert was found covered in his mother’s blood, unharmed. The eight kids scattered different directions when Dad was sent to prison. Robert lived with an uncle, the two became close, and then? This uncle shot a gas station worker. While Robert was in the car. Cops whisked away the one person looking after him. Mentors passed away. One brother hung himself. One brother was locked up for murder. One overdosed on cocaine. It’s all chronicled in “Strength Coach: A Call to Serve,” written by the man who’d train Robert in college. As Jeff Connors later explained, it became Robert’s mission to be the best father imaginable.

Dad spent long nights reliving his surreal childhood with Zay.

Son needed to know Dad survived with a drive.

Any family Robert did have didn’t give a damn about football. He’d lie about going to practice because everyone dismissed the sport as a waste of time. After posting a 1.7 GPA, Robert went to prep school, earned a B average and made it to East Carolina University where, at linebacker, he was a Butkus finalist in leading ECU to an 11-1 season. Drafted by the Dallas Cowboys in Round 1, Robert Jones then won three Super Bowls and started 128 games over a 10-year career.

The baby born in blood became a man dousing Barry Switzer with a Gatorade bath in a Super Bowl triumph.

“That’s not by mistake,” Zay Jones says. “I don’t believe in coincidences. Things are set in motion for a purpose. The energy, the love, the effort he put into his craft is the reason he was in the position he was. I respected that so much getting older. He did it for 10 years, won three rings, raised six kids, faithful to his wife. Married to my Mom going on 30 years now. That, to me, has been humbling. There’s really no words.”

Son had a loving family. And football support. And genes. had a strong support system. His mother’s brother was also former Cincinnati Bengals quarterback Jeff Blake.

But a will to work — that same drive powering Dad — proved to be his greatest weapon.

Whereas Cayleb was the 21st-ranked wide receiver in the country and attended Texas and Arizona, whereas Levi theatrically spurned Florida and Florida State for USC, middle-child Zay was an afterthought. He wanted to stay in the state of Texas — UT, TCU, A&M, Houston, Baylor, wherever — but nobody was interested in a receiver who caught 36 passes for 439 yards as a senior. The radio silence, he recalls, was “disheartening.” As countless peers posted their national rankings, he was a two-star footnote. But, he quickly adds: “I never lost the faith in my work ethic.” When ECU offered a scholarship, Jones maximized the opportunity. Off the field, he had a 3.6 GPA and strove to change lives. He led the team in community service hours and the term itself — “community service” — makes him cringe. It sounds obligatory. Like punishment. At heart, his Christian upbringing called him to serve. Take one teenage girl battling cancer on a hospital visit. Zay couldn’t just leave her and forget her. He stayed updated on her condition and bought her Christmas and birthday presents.

Bring the girl up today and Zay lights up.

“Giving back,” he says. “Loving people. Going to peoples’ homes. Eating with them. Praying with them. Loving on them. Me learning something, too.”

On the field? He set goals. Crushed goals. Proved everybody wrong. Nobody in the 153-year history of college football history has caught more passes than Jones.

He finished with 399 receptions. Many of the absurd variety.

Before his final season, new receivers coach Phil McGeoghan called Jones into his office to meet. Zay remembers giving him the same back story he details here and seeing McGeoghan uncap an Expo marker. Standing at the whiteboard, he asked for Jones’ 2016 goals. Zay didn’t hesitate: Win a championship. First-team All American. Catch 150 passes. Eclipse 1,500 yards. Score 10 touchdowns. Jones of course obliterated those numbers. Mainly because he felt so comfortable in his underdog role. That kid making his bed every morning had every reason to pump out two more reps in the weight room. Nobody expected a thing from Jones out of high school. Mentally, this is the healthiest space for any athlete to exist in. The reason every football coach in the history of mankind has tried convincing his team, “Nobody believes in you!”

Zay took a match to the record books. He had fun, too. He makes a point to assure he, ahem, enjoyed the fruits of such labor.

“It was such a beautiful time in my life. Especially for someone who felt so undervalued at least in the eyes of football growing up.”

On to the NFL, he fully expected to be a Los Angeles Ram. This was the team that flew right to ECU to work him out. GM Les Snead was present. First-year head coach Sean McVay, too. And QBs coach Greg Olsen. And receivers coach Eric Yarber. The Rams even brought in their own quarterback to throw. Leaning in, Jones relives that day with a hilarious McVay impression.

“OK, Zay! Alright man. Let’s see you run a choice route. … Man, you’re fast! You’re quicker than I thought.”

So when three wideouts quickly flew off the board — Corey Davis (fifth overall), Mike Williams (seventh) and John Ross (ninth) — and he was forced to wait… and wait… and wait into the second round, Jones didn’t panic. He knew L.A. would take him the next day with the 37th overall pick. They were on the clock. His phone rang. Only, it wasn’t the Rams. It was the Bills. Huh? The voice on the phone informed Jones the Bills had traded up to No. 37. They asked for his social security number. His official name. His nearest airport. At one point, Jones put his hand over the speaker and whispered to Dad, “I think the Bills are drafting me.” Both stared at each other, dumbfounded, because Buffalo didn’t seem interested at all through the predraft process. The team did however have a new wide receivers coach who told Sean McDermott everything he’d need to know: McGeoghan.

Jones couldn’t point the city of Buffalo out on a map. Nor did it matter. When Hall-of-Famer Thurman Thomas announced the pick, Dad wrapped his anvil of a bicep around his boy’s neck and Zay’s tears flowed. This was the apex of more sacrifice than anyone knew. And then what should’ve been one of the best days of his life — Jones snaps his fingers — was “quickly ruined.” No way did Jones think the ESPN cameras would broadcast him live on Day 2, so he ditched his dapper Day 1 outfit for a t-shirt bought earlier that day in Arizona.

A tee featuring a convoy of white Bronco trucks pursuing a police car. Whoops. He was thoroughly lambasted on social media for being insensitive. Even though Jones wasn’t born yet when O.J. Simpson and Al Cowlings led police on 60-mile car chase in Los Angeles.

“C’mon, I wasn’t even thinking,” Jones says. “I thought it was funny. But I didn’t mean to support OJ.”

He was forced to apologize to ownership. To McDermott. To the fan base. Then, in an interview with the local media over the phone, he accidentally referred to his new coach as “Scott McDermott” with his college coach, “Scottie Montgomery,” still on the mind. This led to more criticism, even though he had never even met McDermott before. Those Rams got around to drafting a wide receiver at No. 69 overall, by the way, named Cooper Kupp.

All a fitting omen.

Zay finally made it to the NFL. But his life was about to fall apart.

‘Depression’

The butterfly effect is very real in pro football.

Especially for rookies.

Six minutes into his NFL career, Zay Jones glided free along the back line of the end zone. He toasted his man — exactly as he did at ECU in his sleep — but the quarterback didn’t see him. Instead, the ball was thrown to another receiver near the front line. Tipped. Picked. Returned 48 yards. Score a touchdown this soon into his NFL career and Jones is certain the trajectory of his career completely changes.

Instead, he finished that win over the New York Jets with one catch.

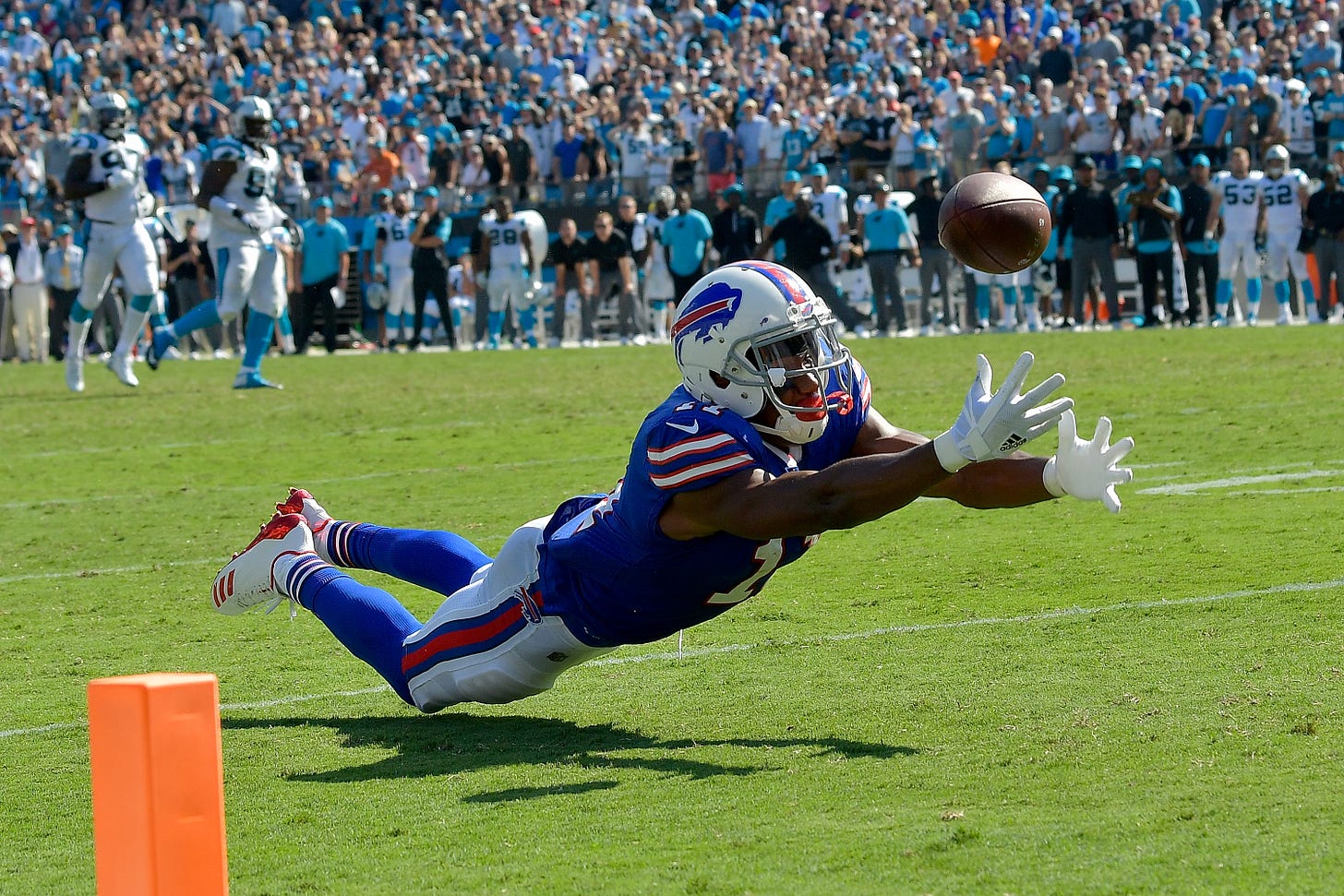

Instead, the next week, his Bills marched downfield with a chance to upset the Carolina Panthers and a different play changed his life.

Buffalo trailed, 9-3. Fourteen seconds left. Fourth and 11 from Carolina’s 33. This play wasn’t scripted. Wasn’t even repped in practice. But Tyrod Taylor saw a soft spot in the deep corner of Carolina’s secondary and essentially drew it up in the dirt. (“His thought process,” Jones recalls, “was way beyond where I was at.”) At ECU, Jones ran his share of corner routes but never with such nuance. The angle, the timing in which Taylor wanted this executed was precise.

Jones accelerated toward that pocket of the field, leapt, twisted 180 degrees, fully extended, got both of his 9-inch hands on the ball and… could not hang on.

For six seconds, he laid motionless on his stomach at the 1-yard line. A man shot in combat.

What happened next was novel in his football life.

“I did not realize how, let’s say, passionate Bills fans can be,” says Jones, smiling. “I came from an underdog kid at ECU to being glorified. I never had any expectations because no one knew about me. Then you go break all these records and everybody says, ‘You’re the greatest thing.’ That’s the first time I ever received true criticism. Publicly. Think about it. Undervalued in high school. No one cared. Underdog at ECU who grows to be this star. I could do no wrong at ECU. As soon as I got to the league, that was the first time that I had people literally say, ‘You suck.’ And I didn’t know how to respond to that.”

He couldn’t stay off social media because he had no actual social life. Jones explains that he lived inside a one-bedroom apartment a short drive from the stadium in Orchard Park, NY called “The Hammocks,” which… come again? I tell him that’s exactly where I lived that fall and, after connecting a few dots, we figure out that Zay lived right around the corner. I never saw him. Nobody did. After four years of partying with friends, he was now a loner.

A no-show the following week against the Denver Broncos — 0 catches, 0 yards, 0 touchdowns — officially rendered him a hermit.

“I never came out of my house,” Jones says. “I was going through a really hard depression. I didn’t know how to really respond from that. More and more kept overtaking me.”

Storms converged.

The dearth of talent at wide receiver — the Bills had shipped their WR1, Sammy Watkins, off to the Rams for a draft pick — meant Jones faced every team’s best corner. Stephon Gilmore, Morris Claiborne, Marcus Peters, Casey Hayward, Desmond Trufant were sharks compared to the guppies in the American Athletic Conference. The Bills had his old college coach on staff but it’s not like McGeoghan could kick out as an “X” receiver and allow Jones to motion into the slot against an inferior DB.

The head coach’s gruff coaching style made matters worse. Jones describes McDermott as a “lunch pail guy” and does credit him for being manically detailed. But he also calls him downright “intimidating.” During meetings, McDermott would spontaneously grill players. Ask Jones, for example, to name the top three coverages the Baltimore Ravens run on third-and-“2 to 6.” When Jones answered Cover 3, McDermott pressed him. Which type of Cover 3? Such a high-pressure environment was a natural pendulum swing away from Rex Ryan’s country-club ways. But wind everybody up this tight year ‘round and players will inevitably crack.

Says Jones: “He would ask these questions that would freak me out. It wasn’t the best thing I needed at that time. Not that I needed to be coddled. But I really needed someone to take me in and start showing me how I can win these matchups.”

Thirdly, the most devastating blow to his sanity struck in Week 8. Against the Oakland Raiders, Jones was body-slammed by linebacker Bruce Irvin on a shallow route. His shoulder snapped. He tore his labrum. The pain paled in comparison to the fear Jones felt in fans labeling him a bust — so he refused to sit out. Refused to tell people about this injury. Even slipped a sleeve over his brace so fans wouldn’t see it and think he was using it as an excuse.

Many nights, he’d hole up at the Hammocks. Call Dad. Sob.

Teammates Tre’Davious White, Jordan Matthews and Jordan Poyer all helped. But he was sad — “hella sad.” The longevity of an NFL season took its toll. To cope, Jones found comfort in bottles of wine. Far more than he should have consumed. Part of it was a matter of feeling sorry for himself. Part of it was not being ready to be a professional — paying bills, finding hobbies. He notes that the sun didn’t come up for months. A true statement, as all Western New Yorkers can attest.

Zay Jones didn’t want to play football. Period. The sport wasn’t fun anymore.

“I didn’t know how to ask for help. Isolation killed me. There were a lot of expectations for me to thrive and take Buffalo to the next level. And to be honest, I think I had the ability to but mentally I was not there yet.”

His NFL introduction eerily mirrored the receiver he replaced. Watkins also struggled with criticism. Watkins also tried to numb emotional pain with alcohol. He’d drink alone in his basement until 4 a.m. Injury to injury, Watkins felt like he was letting down everyone back home in Ft. Myers. Bad turned to worse when his brother and a slew of other friends and family members were arrested in a wide-sweeping RICO case. Watkins paid the $1 million bond in waging this debilitating “war outside of football.” Little did Jones know he’d also discover a new low. A midseason trade for Kelvin Benjamin supplied temporary relief. The overweight vet caught all of 39 passes in 18 games as a Bill, but this presence of a former 1,000-yard receiver took some heat off Jones. The Bills even made the playoffs, breaking a 17-year drought.

That same January, Jones surgically repaired his shoulder. More relief. Cayleb tweeted support: “I’m proud of you for dealing with everything you’ve been faced with this season,” he wrote. “You are a soldier Zay. Your bright future is inevitable. I love you brodie.” To which, Zay quote-tweeted a heartfelt response: “This year is our year. Just wait, God’s plan for us is greater than we could imagine.”

Two months later, the two brothers were arguing high up at Apex The One apartments in Los Angeles.

Initially, Jones skips right past these events. As if this isn’t worth our time. Bring L.A. up a second time — Is this a moment you bury forever? Or learn from? — and Jones begins by saying he has definitely tried to learn from it. Yes, he was with bad dudes. Yes, he was likely tripping on something. The play-by-play account of that night remains cloudy, but not his general state of mind. Jones was still depressed, and brings up another layer to his stress: Money. He felt a suffocating burden to take care of certain people close to him with many others — who weren’t close to him at all — also asked for handouts.

“When we talked about, ‘Were you sad?’ Yeah, bro. I was down a really dark path,” Jones says.

Officially, Jones was arrested for vandalism. A rep for the building said Jones caused $20,000 in damages. He could’ve had a toxicology administered but feared it would’ve put him in more trouble. Per the LA County’s District Attorney office, Jones’ family paid the complex restitution. Further, the only video available of the incident was the surveillance recorded by a tenant (the TMZ video). The building’s engineer said there were no cameras on the 30th floor. Shudder to think what it would’ve revealed. A cooperative victim, plus a lack of proof in establishing a number for property damage, plus the lack of “malice” meant Jones avoided legal trouble.

Prosecutors basically decided this 22-year-old had been through enough.

No, Zay Jones didn’t merely kick that window on the 30th floor. He attacked that window, full force, with his entire body. Which explains why there are now scars all over his body. None of this made any sense to those who forever viewed Jones as the gentle soul you’d want your daughter to marry. That night took a reputation he had spent his entire life building and neatly slid it into a paper shredder. If Roger Goodell sat down with the script writers himself, he wouldn’t imagine something so sinister. Perched above the video was TMZ’s headline: “Insane Nude, Bloody Arrest.”

“People were calling me ‘meth head’ and ‘crack head’ and telling me I did PCP and telling me I needed to go smoke ketamine,” Jones says. “People were saying, ‘He’s definitely on Fentanyl. People were telling me I was ungrateful — ‘How could you? This is what happens when you give a spoiled kid money. They don’t care.’ All these things I had to maneuver through and see at face value. Not that the comments were true. But some of it was warranted. I could’ve been better.”

Once he realized how lucky he was to be alive, Jones looked forward. Only forward. He decided to use the lingering humiliation to inherently change him for good. His entire life, Jones was a people-pleaser. He yearned for anyone to recognize his talent. Be it a scouting website or a parent in the stands, Jones craved such validation.

From March 19, 2018 on, he stopped caring what anyone says.

“Someone could look at me and say, ‘Zay, I think you’re a f--king idiot.’ And I would just be like, ‘Hey, man. Love you.’” Jones says. “I’m not here to win your approval. At all. That doesn’t mean I get to be an arrogant a-hole. But I’m not here for you to validate me. I’m going to be as kind, as loving, as gracious as I am. And if you don’t like me? You don’t like me.”

This took weeks. Months. More awkward encounters than he can count. Back in Orchard Park, Jones was paralyzed with paranoia. As if literally “everybody” saw the video. He’d push his cart through the grocery aisle at Wegmans and notice people staring at him. Did he see the video? Her? Oh no. Then, bold strangers would straight-up ask Jones what happened that night in L.A. His response? Nothing. He’d simply pick up his go-to peanut butter, jelly and bread — because he had no clue how to cook — then head to the checkout.

Jones was never angry at those fans. He loved their devotion. Supporters seriously live as if they’re going through every drill with you, he says. Every practice. Every game. They, too, wake up Monday morning in excruciating pain. He’s not exaggerating. The Bills aren’t entertainment for locals — they’re the direct source of joy, of despair. Fans believe in their heart the Bills are their team, Jones adds, and he sees “beauty” in that.

Over the next two years, Jones quit caring what anybody thinks about him. Cold turkey.

“It’s never fun when you’re on the Internet naked when you didn’t want to be,” Jones says, with a chuckle. “But it gave me such a superpower because I’m like, ‘Well, I almost died. Everyone is making jokes about me.’ For people who are really going through real problems — who don’t know where their next meal is coming from, parents losing a child — I feel like as clear as you can make life, that’s the greatest form of life. Not to overcomplicate it.

“I’m here. I’m here for a reason.”

Like his Dad one generation prior.

That ‘18 season, with four different QBs, including rookie Josh Allen, he led a transitioning Bills team in receptions (56), yards (652) and touchdowns (seven). McGeoghan was gone, fired after the one season, with a new OC in town. Into ’19, the front office paid up for John Brown and Cole Beasley, additions Jones believes “X’ed” him out of the offense. When he brought his concerns to the coaches, the Bills told him to stop complaining. To stop thinking about himself. “When honestly,” Jones adds, “that was not in my heart.” A ghastly offensive performance vs. New England in Week 4 was the final nail. The Bills threw three interceptions, fumbled and had one punt blocked for a touchdown but one fourth-and-goal ball also sailed through Jones’ fingertips.

So, he was the scapegoat. The next week, in Tennessee, Jones played one snap.

“Gut-wrenching,” he recalls.

When GM Brandon Beane called him afterward, the receiver expressed that he wanted to play for the Bills and be a piece of this passing game. This GM didn’t draft him but, as Jones recalls, he promised to get a conversation going with all parties involved. “We love you,” Beane said. That bye week, Jones headed north to Toronto for a brief respite — he now understood Buffalo’s geography — and, 10 minutes from his hotel, he received a call. It was Beane. And McDermott. Jones decelerated off the nearest exit, parked near a barren office building and the two said they had traded him to the Oakland Raiders.

Jones asked if this was a joke. He didn’t believe them. Not that he thought they were being cruel. This simply didn’t seem possible. The two assured him the trade was, indeed, legit and that both Mike Mayock and Jon Gruden were thrilled to get him. They said he’d need to head back to town to catch a flight to Oakland at 6 a.m. the next morning. It was dark. He was in a different country. The news hit ESPN. His phone blew up with concerned family members: Did you know about this? Where are you? Are you OK? And as his world changed, Jones sat in total silence — “in awe” — watching all the cars zip by at high speeds on the highway.

For a split-second, he felt all alone again. He said a prayer to God, shifted into drive and drove the two hours south.

To this day, Zay Jones is proud of the thoughts that naturally raced through his mind in that moment. He didn’t sulk. Didn’t cry. As much as he wanted to remain a Buffalo Bill, he was not resentful.

“I immediately started a positive outlook,” he says, “in thinking of my future.”

It was time to take his life back.

‘Pit to palace’

There were no gawkers in Aisle 5. No whispering, no snickering. Wherever Zay Jones went in public, as a newly minted Oakland Raider, he was a man with no name.

His face wasn’t on posters. After the Bills bailed, Jones had zero clue how long he’d even be on an NFL roster. So when the Raiders gathered for a “1-2-3-Family!” before his first game, Jones was mum. He couldn’t say the word because he felt like this was their team. Not his. For 11 weeks, he lived in a one-bedroom Alameda, Calif., hotel room that cost $3,400 per month. Triple the cost of life in the Hammocks.

There were zero guarantees. Zero expectations.

Total anonymity that makes him glow to this day.

“I’m simply a role player who may not be on the team next year,” Jones says. “There was freedom in that for me.”

Precisely when Zay Jones was dead to the world, he rebuilt his life. The turning point, easily, was life in Oakland. A place “of rebirth,” he says. He’s careful not to criticize the Bills organization because of all relationships cultivated. Jones even hit it off with Beane’s son. He cared for Allen, for McDermott. But with a wry smile, he thanks the team for delivering the two greatest milestones in his life: Drafting him and trading him.

New relationships led to new perspective. Very soon, he heard all about Darren Waller’s near-death experience. How the tight end battled drug addiction as early as age 15 and the addiction only worsened from high school to college to the pros. How Waller would drink five times a week and consume Molly, Xanax, Adderall. “Anything that can change the way that I feel,” Waller once told HBO’s Real Sports, “I was pretty much down to try it.” He spent $100 per day on pills. He was suspended by the NFL for a full season. And, in 2017, he passed out in his car for hours after taking pills laced with Fentanyl.

Here, Jones leans back in his chair, arms outstretched and stares up at the light.

“Dude! That changed me. I said, ‘If this guy could OD in the back of his seat and come back and be a Pro Bowl player, why can’t I?’”

Jon Gruden was the right coach at the right time. Not only did the coach bring a love for the game that re-energized him. Jones felt respected. He channels his inner-Gruden with another standup-worthy impression: “Now, why in the hell would anyone from Buffalo get rid of Zay Jones? This is one of the smartest players I’ve ever freakin’ coached in my entire life.” This head coach empowered Jones to believe, once again, “I can play this game.”

Take one route that Gruden treasured in his playbook. On the “22-yard hinge,” the quarterback carries out a deep play action with the wide receiver sprinting downfield between the numbers and hash. At 22 yards, the receiver shuts it out. Abruptly. This route was never called for Jones with so many ahead of him on the depth chart. But he knew Gruden valued it, so perfecting this hinge route became his mission. Nonstop, he asked quarterback Derek Carr to rep it. And Carr — described by Jones as “Gandhi himself” — happily obliged. The two wouldn’t even work on-site, instead heading to a completely different location.

And, as luck had it, the Raiders’ mainstays were struggling with the route at one point. Once more, Jones goes full Gruden: “Give me Zay Jones. Let’s see what you got, man. Don’t mess up my route. I’m giving you a shot!’”

Jones ran the route crisply, screeched to a halt, caught the pass. This was his Super Bowl.

“No one will ever see this play,” Jones says. “But it was a pivotal moment for me. Because something as small as that in practice, I was like, ‘Dude, coach called on me and I made the play.”

He was barely targeted on gameday — 1.8 times per game his first 1 ½ seasons as a Raider — but if the ball was thrown his way? “I’d catch it,” he says, giddy. He felt like that kid at East Carolina proving himself all over again. He was hungry, but not for validation. Not for scholarship offers. Ever… so… slowly… he rebuilt his confidence. Before the Raiders moved to Las Vegas, in 2020, Jones bought a home right in Sin City. That March, he put roots down to commit himself to making the team. All potential vices, ignored.

There’s a good chance we’re not sitting here without “Gandhi,” either. That offseason, Jones asked Carr to throw routes. Constantly. A father of four, Carr squeezed in as many sessions as he could upon moving to town. The duo would throw at least three times a week at 6:30 a.m. — Monday, Wednesday, Friday. If Carr needed to catch a flight at 8, he’d get there by 5:30, 6. No sweat for Zay, thanks to his Dad. Never training later than 8, they drilled every route: Slants. Quick outs. Curls. Daggers. Hinge. Oscar. Carr would airmail a deep ball to Jones, then jog downfield to run a route the other direction.

All along, the two discussed life as much as football. Jones learned of Carr’s spiritual awakening, how he turned his life around in college.

“He’s phenomenal,” Jones says. “Derek Carr is a man set apart but lives like he’s above no one. Derek will talk to anybody. You’ll tell Derek you’re going through something and Derek will be like, ‘I’m going to pray for you.’”

Firmly on the bubble, again, Jones beat out the same player Buffalo essentially replaced him with two years prior: John Brown. Week 1 arrived with Allegiant Stadium welcoming a packed stadium for the first time post-Covid. A battle cry from Bruce Buffer. A blinding-white suit coat from Mark Davis. Hall-of-Famer Charles Woodson in the same suite. The Monday Night Football stage was set.

And into overtime, Zay Jones reintroduced himself to the world.

Expecting a run, the Baltimore Ravens deployed Cover 0. All Vegas needed was a field goal to win, so it made sense for any offense to run into a brick wall and hope for two yards. Instead, the Raiders went for the kill. Carr checked to “Riddler,” a kill shot to a receiver dashing diagonally across the field. Jones dusted All-Pro corner Marlon Humphrey with a left-right-left off the line and found himself all alone for the 31-yard touchdown. Game.

Jones finger-rolled the football and ripped his helmet off to show the football world his face. The first teammate to embrace him? Waller, one of the few people in the sport who understands what Jones endured. A few moments later, Carr was interviewed by ESPN on the field. He couldn’t wait to tell the world what fueled this moment. Adrenaline was still pumping full blast. Pointing a finger to drive his point home, Carr said Jones never missed one 6 a.m. throwing session.

“I hope everyone in the world roots for Zay Jones,” the QB continued, “because he works harder than anybody on our team.”

Just like that, the nation had a new image to conjure upon hearing Zay Jones.

As a relentless worker. What he’s always been.

He was back.

Says Jones: “Palace to pit to palace.”

As other careers were nuked, Jones took off. Which made for a bizarre dichotomy. In October, Gruden was forced to resign after his “shameful” emails were leaked. In November, Ruggs killed a woman at speeds of 156 MPH. His BAC was twice the legal limit. One week later, video surfaced of cornerback Damon Arnette flashing a gun and threatening to kill someone. Both former first-round picks were swiftly released. Jones, meanwhile, “started spazzing” each Sunday. A circus grab vs. Philly on third and long for 43 yards. A steely 15-yarder vs. Cleveland on a crossing route — with 16 seconds left — to tee up Daniel Carlson’s game-winning field goal. A 120-yard explosion vs. Indy in a must-win.

Jones rocket-fueled the Raiders’ playoff run by learning to relish NFL pressure.

“That I’m here, I’m capable. I’m built for it.”

He was always hopeful he’d find himself after that drop in Carolina, but Jones had no clue how. It’s not like Mr. 399 suddenly forgot how to catch a football and, honestly, nobody gets to this level without an extreme amount of talent. No pro sports league weeds out bums quite like the NFL. And unlike the NBA (82), NHL (82) and MLB (162), there are only 17 games in an NFL season. Seventeen opportunities to justify your existence on a roster or get replaced by someone younger, cheaper. That’s why everyone who endures the sport’s ups and downs insists football is far more mental than physical. Surviving in pro football is more about how a wide receiver mentally responds to dropping that potential game-winner in Carolina than the literal physical ability it takes to make the play.

So, how much of this specific comeback has been pure belief? The man in a gray Jags crew can’t answer fast enough.

“Ninety-nine percent.”

‘Untouchable’

Once the parasite, Urban Frank Meyer III, was extracted from the building with tongs and flicked away to a Fox broadcast booth last year, the Jaguars promptly hired a Super Bowl champion (Doug Pederson) and entered the most crucial free agency in the franchise’s 29-year history.

The team was armed with both $36.9 million in cap space and a quarterback, Trevor Lawrence, deemed #generational since his first sonogram.

There’s the luxury of spending money when your QB’s on a rookie deal. Then there’s this.

Of course, it’s simplistic to suggest one Supermarket Sweep-like raid of free agents those first 48 hours guarantees success. Endless veterans get paid and throttle down. Human nature in a violent game. The culture was also an abomination the year prior in Urban Land. Talent alone would not suffice. The Jaguars knew they needed to acquire leaders fully capable of replacing last year’s dictatorship with a true democracy. Doug Marrone wasn’t exactly the great unifier pre-Urbs, either. This was an organization with all of one winning season the prior 14 years.

Everything a chart of numbers cannot reveal mattered most.

So, they did not care as you laughed away. Jacksonville spared no expense in signing Brandon Scherff (three years, 49.5M), Christian Kirk (four years, $72M), Evan Engram (one year, $9.2M) and Jones (three years, $24M) on offense alone. These four were identified as personalities capable of spearheading a new player-run operation. All the Jaguars kept hearing was that they’re leaders, set a tone in meetings and need to be pried off the practice field. Offensive coordinator Press Taylor didn’t promise anyone stats, instead asking all to set the example. Jones loved that his new OC cut to the chase.

Taylor told him that he knew he went through a dark time but that the team believed in him as “a person.”

“He brings so much to our team,” Taylor says. “He’s one of the high-character guys. Works his tail off. Gives us all he’s got every play. We ask a lot of him. He’s involved in run, pass, he does a lot of dirty work for our offense.”

Kirk has actually known Jones for years. He calls him family — “like a brother.”

“One of the words I use to describe Zay is perseverance,” Kirk says. “And intellectually, he’s one of the most advanced people I’ve ever been around. Just the way he’s able to decipher and cognitively go through information on the field. The conversations you have with him, he’s different. That dialogue is so great and so genuine and so true. He brings a lot of energy. He’s always rising to the occasion when his number’s called. I love playing with him.”

The contract was full proof that Jones had officially reclaimed his reputation. He then backed it up with a career year: 82 receptions, 823 yards and five touchdowns. Again, he was the catalyst behind an improbable playoff run. Because much like Young Zay in March ’18, the ‘22 Jaguars season appeared to be in ruins. At 2-6. Then, 4-8.

Repeatedly, his number was called with the team’s season on the line. The Jags won six straight.

Baltimore. His 11 catches were the most by a Jag in nine years. He saved his best two for last — a diving snag on third and 6 that set up a TD, and a 2-pointer. Down 28-27, with 14 seconds left, Pederson went for the win. Jones motioned left, froze corner Brandon Stephens with a shimmy and coolly caught the game-winner. Dallas. His catch with five seconds left set up the field goal that forced OT. Somehow, he kept his focus as the ball traveled right through the arms of safety Donovan Wilson. He scored three touchdowns earlier. (This double move should be a felony.) L.A. Chargers. After falling behind 27-0, the Jaguars needed to be perfect. They were. Jones had one of the touchdowns to slice the deficit but his best play, easily, was sealing the edge as a blocker on the famed fourth-and-1 run call before the winning kick.

Pederson is a coach who chooses to believe in his players with the season on the line. Doesn’t matter if he’s got Nick Foles in the Super Bowl vs. Tom Brady.

The crucible doesn’t frighten him. And it definitely doesn’t frighten Zay Jones.

He now feels no nerves in a profession that eats countless grown men whole.

“Why be fearful at all?” Jones says. “Let go of the expectation of others. Let go of others’ opinions about yourself. Enjoy the moment in the present because it’s truly all we have. And it’s precious and it’s vital. Let the result be. Don’t be so fixated on winning that when you don’t win, it hurts you. And don’t be so afraid of failure that you’re not willing to try new things. For me, it’s building a beautiful balance of finding peace in the moment, being at peace with what has happened, letting go of things I can’t control and it’s easy when you’ve got guys who want to be here and have the same vision as you.”

Money doesn’t provide this clarity. He’s already made $18 million. Nor touchdowns. He has scored 18 times. Nor a repaired public image.

The answer, for him, was simple. Flatly, there is no way to tell the Zay Jones story — to understand how he emerged from his darkness — without understanding his relationship with the messiah he referenced in that TMZ haze. He goes down this road without outright preaching. Jones begins by saying he has sinned. In a “fallen, broken world,” he realized he cannot do this alone. Once you’re aware of Jesus Christ’s sacrifice, he adds, a true transformation is possible. He doesn’t do good deeds to profess “I’m a good person.” Rather, to see a “reflection of God” in himself.

This is what he calls the entrance of the Holy Spirit. A “supernatural” calling in his life.

We’ve heard this testimony. From Demario Davis to Trent Sherfield to Kevin Kolb. It’s objectively true that many of the sport’s happiest players are actively religious. Like Zay. The best way to deal with NFL stress is to let go, to believe you’re truly part of someone else’s plan. He sure does. He says he doesn’t buy the whole “universe speech” because the universe needs a creator. “If I were to give you a bottle of water in the middle of the desert,” Jones posits, “and you had been thirsty for weeks, would you thank the bottle of water or would you thank the man who gave you the bottle of water?”

Perhaps there’s even a correlation between our nation’s startling spike in depression rates and plummet in faith, and all of us who don’t pray enough should heed wisdom from Rev. Zay.

Most athletes in that viral clip are ejected from their respective sports in a year, maybe two, and don’t tip-toe back into the public sphere for a decade. Minimum. A 30-for-30 or something. They’re not hearing their number called in the huddle with the season on the line.

“I won’t sit here and say I’m the most perfect human — obviously,” Jones continues. “But nothing gives me more peace than Christ. I won’t shy away from saying that. I’ll be remiss. It’s not fame. It’s not my followers. It’s not even my bank account. Because they’re here today, gone tomorrow. One day football’s going to end for me, and we’re going to have to answer the big questions: What values do we stand on? Who do we protect? What are we guilty of? I’m telling you, if you can accept that you’re in need of a savior and you need a change? There is more grace and more mercy for you than anything. I know some people are like, ‘I’m afraid to be judged.’ Well, you’re going to be judged by something here on this earth or something greater.

“Now, my mission — my whole outlook on life — is completely different. You’re untouchable, bro. You’re untouchable in a sense that small things don’t bother you.

Briefly, as a Bill, he forgot to let go. He vows to never put too much pressure on himself ever again. He’ll keep making teammates laugh with his impersonations. The key is picking up on a person’s unique “tick.” He’ll make a game-saving catch. He’ll read the Bible. He’ll acknowledge those scars all over his body, and live by the tattoos on his leg. The No Matter Where references family. (“No matter where my family goes. I’ll always be there.”) John 14:6 is the Bible verse he lives by. (“No one comes to the Father except through me. Those are Christ’s words. Not mine.”) And then there are the words Not Home Yet.

This one is a reminder that earth is not the end-all, be-all. He believes in the afterlife.

He looks forward to those pearly gates.

But that relocation can wait.

He’s not quite finished down here yet.

Thank you for making Go Long part of your day. Miss a previous Jags feature at Go Long? A handful below:

Excellent article! Always amazed how despite the money and resources, these guys can still struggle to get the help they need to succeed at the next level.