Laviska Shenault Jr. sees the light

At age 10, he experienced unfathomable trauma that should've crushed him. Instead, what happened that day created a "monster" and — yes — there's hope in Jacksonville.

JACKSONVILLE, Fla. — The break of dawn is when he’s happiest. There’s no better feeling than waking up in the morning. He’s not groggy. He’s not demanding a cup of coffee before anyone tries talking to him. Laviska Shenault Jr. sincerely cannot wait to attack the day because he’s overwhelmed with hope.

Every sunrise directly fills the Jacksonville Jaguars wide receiver with optimism.

Whatever happened yesterday is behind him.

“Like a cloudy day and the rain goes away,” Shenault says. “You see the dark come back to light, it’s like a fresh start. The start of something. You never know what’s coming but it’s the start of something.”

He didn’t always feel this way. For most of a decade, Shenault was trapped in the darkness.

One day bled to the next. The sun came up, the sun set, nothing changed and, of course, the reason is what happened on July 17, 2009.

Trauma that should scar 10-year-olds beyond repair.

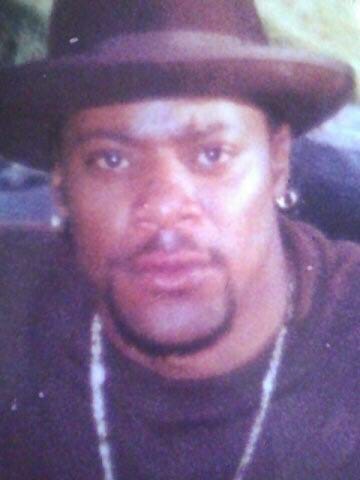

That night, the Shenault family was driving home on Loop 12 from a pool party in De Soto, Texas. Five kids were in the vehicle. Laviska Sr. thought his wife was driving too slowly so he asked to take the wheel. They pulled over and — wearing slippery footwear — Dad stumbled into the road. One car nicked him. Then, a Ford F-150 struck him head-on and his body traveled 50 yards from the point of contact.

In the backseat, one sibling was able to cover the eyes of 8-year-old La’Vontae.

Laviska? He was not spared this sight. Sitting between his parents in the front seat, he saw it all.

Everyone sobbed uncontrollably, unable to comprehend the insane scene.

Laviska? He didn’t shed a tear. He displayed zero emotion.

His whole world went black. “Just black,” he says. Upon returning home, family members were still wailing, still struggling to accept this incomprehensibly grisly sight as reality. Meanwhile, Laviska Jr. walked to his bedroom, closed the door and collapsed on his bed. In that moment, it felt as if his own soul exited his body and he was mere flesh and bones.

“Nothing else in the world mattered,” Shenault says. “Basically, it just felt like everything was pointless.

“I was in a black hole or something.”

He couldn’t see a light then. How could he?

How could any kid even wake up the next day?

Pose this question to Shenault, and he stammers. He stutters. He does not know. He cannot explain it. That day felt something like a movie, he says. A “crazy, crazy moment” that inherently changed him in real time. The sun did rise. The sun did set. One day to the next. Yet in that black hole, he stayed. As a tribute to Dad, Shenault let his hair grow. Through his entire childhood, on to college, Shenault struggled to find himself.

The trauma hardened him. He didn’t cry, like really, really cry, for years. Both emotionally and physically — for better, for worse — Shenault became impervious to pain.

Yet, here he is smiling at Jaguars HQ. He’ll turn 23 years old next month.

He’s just now truly turning a corner in every possible way.

Forty-eight hours before his 2021 season begins, Shenault walks into this office room, sets a purple Gatorade down and lounges in a leather chair. His feet are crossed. His wild dreads are wrapped neatly in the back. His nose ring sparkles. It’s taken 13 years but Shenault is busting out of the shell. This “wide receiver” in name only cannot wait to go full “Hulk Viska” on NFL defenses this season.

He calls himself a “different type of monster.”

“This monster is a tough monster,” he says. “A hungry monster. A determined monster. A person who wants to be the best and be legendary. I’m trying to accomplish things nobody has.”

Forget his bizarre 7-target, 2-reception, -3-yard performance against Denver in Week 2 and forget that shoulder injury that required an MRI. He knows the sun will always rise the next morning. He’s set to play this Sunday against the Arizona Cardinals. And these Jacksonville Jaguars the entire world has deemed destined for an eternity in hell won’t be stuck in darkness forever.

They’re led by a weapon who not only miraculously recovered from that trauma — he’s thriving.

As a person and, of course, as a player.

Now when Shenault tries to imagine how special he can be on the field, he cannot.

“I’m trying to do something different,” he says, “to where I can’t even answer that question.”

He saw it all. Nobody was there to cover Laviska’s eyes.

Yet that night is still a blur to him.

His Mom, Anna, has since helped him piece it all together and what everyone remembers is Laviska’s blank demeanor. It was odd. Siblings cried hysterically. Mom even tried running into traffic to be by her deceased husband’s side and needed to be restrained by police for her own safety. And here was a 10-year-old hardly blinking. When everybody was sad — to the extreme — he says it felt like his own emotions were “wiped away.” And Shenault was not able to get them back as he developed into a teenager. No, he did not necessarily “bury” the trauma deep into the catacombs of his memory. Nor did he allow it to fester at the forefront.

All of this, simply, became part of who he is.

Shenault has never been a sensitive person and he knows this is the moment why.

Ask him about the unspeakable sight of Dad getting hit so hard his body moved 50 yards and it’s just that: unspeakable. He lets the question hang in the air without saying a word. It does bother him that nobody stopped after his Dad was initially clipped. (“That just shows me how careless somebody can be.”) Cars were moving at 70 to 80 MPH, but still. The sight of traffic moving… moving… moving… only moving remains seared.

“It just kept going,” he says.

And Shenault started to view life through a colder lens. He stopped having much sympathy for anything because everything else in life — understandably — felt trivial.

Absolutely there were days Shenault wished Dad was with him. They were extremely close. One of the last life lessons Laviska Jr. took from Laviska Sr. was to be tough. Always. There was no whining, no complaining, no excuses permitted in his house. He wonders if that was a factor, too. Either way, Shenault has zero recollection of how he exactly coped with this tragedy.

He did see a therapist. But that didn’t accomplish much and it started costing too much for Mom, too.

He did not have an older sibling to lean on. One was already in college. One was about to go to college. One only had a year left in high school. If anything, Shenault had to become the man of the house himself at 10.

There wasn’t much time to heal. More trauma would hit this family.

Three years after her husband died, Anna contracted West Nile Virus. The disease was ripping through the Dallas area in 2012. The symptoms hit Anna hard and, financially, Laviska says the family entered a “scary” place. Putting food on the table became difficult.

Fortunately, he had sports. He hit it off with a kid on his basketball team whose family took him in while his mother recovered. Without this, Shenault has no clue how he would’ve gotten by.

Dad’s death pulled the family apart, too.

Only more and more and more apart.

Shenault clasps his hands tightly together. His family was like “this,” he begins. But after that tragedy? “It was like that.” And he slowly pulls his hands apart. He blames himself, too. He wasn’t willing to open up to anyone. Even with his little brother around, he says he just wanted to be alone. Period.

“That wasn’t a good thing,” Shenault admits. “I didn’t even want to be around family.”

Nor did he have any cousins, aunts, uncles or peripheral family members to go to.

Again, he holds his hands together.

“From when I was young young, all the way up to 10, everything is here,” he says. “Dad died, then everything is slowly… slowly… slowly….”

Again, his hands move back apart.

Dad’s death. Mom’s illness. It all only closed Laviska Shenault Jr. off from the rest of the world.

These days, the siblings try to get together more often. They’ve got a fun group chat, too. As Shenault matured, he realized he wanted to be a Dad and have kids himself one day. He yearns for that family structure he lost at the age of 10. Usually, he adds, parents don’t want their kids to grow up too fast. They want their kids to live in the moment. Shenault has forever resisted that urge. Since 10, he’s been chasing the family structure he lost on Loop 12.

That day did irreparable damage to everyone.

Everything, he says, “went out the window so fast.”

Shenault wishes now that he wasn’t so closed off when everyone else was “super emotional.”

“Now, I really understand that I do want these people in my life,” Shenault says. “I do want to communicate with them. I do want them to be close to me. So that was one of the biggest things that I wanted to work on which I didn’t get to start working on until I got out of college.”

There was one net benefit: Shenault’s playing style became a direct reflection of the trauma.

He feels zero pain and he has zero sympathy for anyone attempting to tackle him.

From high school to college, Shenault refused to go down on first contact. He fought for every inch.

This was no typical high school, either.

DeSoto High School, a 25-minute drive south of Dallas, is run like a college powerhouse. Practices were next level. Workouts? “Oh my God, Shenault says. “There’s no way we can’t be great doing all these type of things.” A turning point in Shenault’s maturation was the summer before his senior year. He needed to attend one of the morning workouts (either the 5 a.m. or 7 a.m. session), yet he also needed money. Anna was trying her best to provide but every dime was hard to come by.

So, Shenault woke up at 4 a.m. to make that 5 a.m. workout.

Then, at 7 a.m., off to Chicken Express he went. He worked double shifts at the fast-food chain, too.

Shenault didn’t have a ton of friends. His reputation as a shy loner stuck, but no one could question his determination. He was going places. Genetics certainly helped. Mom was a basketball player and he’s seen pictures of Dad doing pushups all the time… but he worked at it. As this chat shifts away from the trauma itself and toward what that trauma created — that “monster” within — Shenault’s entire mood changes. He goes from one- and two-sentence answers to leaping out of his chair to illustrate everything he’s played through.

He looks and sounds like someone who has finally accepted what happened on July 17, 2009 and will use it for good.

He will never forgot Dad’s final life lesson, too.

Corners may now want to get the hell out of his way.

He never had to consciously think about being fearless, no. This was his natural state.

That’s obviously a great thing. It earned him scholarship offers to virtually any school of his choosing — Alabama, LSU, Mississippi State, UCLA, etc. That can be a bad thing, too. Very bad. The man’s body is a canvass of scrapes and bruises and scars.

And yet Laviska Shenault Jr. also takes immense pride in these wounds.

His voice is spiked with excitement as the war stories begin.

He has to start with “Sideline Kill.”

Right in the street in front of his house, he’d play games of two-hand touch with friends. And if you were near the edge? Near the grass? You were fair game. You could get “killed.” Once, Shenault was smashed into a metal pole that stood one foot off the ground. He had no clue what purpose this pole served but it broke off at 90 degrees at the top and had a sharp tip that gashed him good. He can still picture the exposed “white meat” underneath his skin and, lifting his pant leg up, Shenault reveals the oval-shaped welt that’s lasted all these years.

The crazy thing? He didn’t even cry until he saw the blood gushing. Even crazier? His family was against stitches. Shenault never went to the hospital, no, he was taken to the bathroom. All he did was rinse that wound under running water.

Next, he slides both of his sandals off and alerts your eyes to the bottom of his feet.

“Does that look the same to you?” he asks.

Most certainly not. The pad underneath the second and third toes on his left foot is much puffier. Why? “A toothpick. A big toothpick.” He stepped on one as a kid and had to pull it out himself.

“I’ve had so many crazy, little ‘What the f---?!’ things,” he says.

Two seconds later, he sticks out his right hand. There’s still a scar here from a hot iron falling off the countertop.

He then points to his arm where tattoos cloud another scar.

This is from a 7-on-7 drill in high school. He ran a go route and didn’t even see the set of track bleachers downfield. Others screamed as he raced closer to those bleachers, but he was too focused. Too locked in on the pigskin spiraling his way. Here, Shenault pops out of his chair and pumps his arms to re-enact the injury.

“I’m looking back and this whole time, I’m getting closer and closer to that bench,” he says. “Boom! You know what’s crazy? Luckily, I put my hand up. I still have a little cut right here. If I don’t put my hand up and get this scar right here, I am not playing football.”

That’s because he would’ve bashed his head into those bleachers. He was moving so fast that he cannot even imagine what kind of damage he would’ve done.

Instead, he only got the wind knocked out of him.

Shenault insists that he doesn’t try to be reckless. Rather, this is who he is: A man with one speed.

There’s one more scar to show, too. He lifts up his shirt to reveal a deep cut across his chest. What caused this isn’t exactly clear but Shenault believes it’s from trying to carry a full-sized basketball backboard as a kid. Right over the scar, since then, he had the words “No Struggle No Progress” tatted. His favorite basketball player, Carmelo Anthony, has this creed scripted across his neck.

Yet these words also epitomize Shenault’s life.

After lighting it up at DeSoto, Shenault chose the University of Colorado over all of those other powers — even Alabama — because this felt like a real relationship. He was able to open up to the coaches here more than any other school. And then, “out of his comfort zone,” he started to open up. Gradually. Like most 18-year-olds, college was an exercise in self-discovery. He finally started busting out of that decade-long shell and found himself. Just not necessarily how you would expect. No doubt, Shenault dominated on the field. In nine games as a sophomore, he caught 86 passes for 1,011 yards and six touchdowns with another five rushing scores.

Six games in, he was a Heisman Trophy candidate. He was leading the entire country in catches and receiving yards per game.

More heartbreak, more darkness then moved Shenault closer to that light.

Against USC, he suffered a Grade 3 turf toe. The ligaments tore up in what he recalls as a “crazy, freak accident.” Colorado was running the hurry-up offense when Shenault lined up at receiver, went to take off and… collapsed. Only instead of his bed, it was the field. When he found out surgery was needed, something extremely strange happened.

He cried.

“It was hard. It was so hard,” Shenault says. “After that game, I had to let it out.”

He only missed three games because he was so motivated to hit 1,000 yards. Yet upon returning, Shenault tried to hit someone and felt his shoulder go weak. He yelled, grabbed his shoulder and the pain throbbed. Pain he couldn’t quite make sense of. Shenault learned that some players — depending on their position — simply play through labrum injuries. So, he did. And his Tasmanian Devil style never ceased.

He remembers spending any off time laying on his couch “just suffering.”

Colorado didn’t make a bowl game so Shenault first had surgery on his toe Nov. 28, then surgery on his labrum Jan. 6. Each procedure required a six-month recovery. The first time he met the team’s new coach, Mel Tucker, the receiver was in both a boot and a sling.

He even needed to teach himself how to drive with his left foot.

Yet, Shenault also knew he was getting stronger. Only stronger.

“Honestly,” he says, “the way I thought about it was, I’m built for anything. I can do anything.”

Into his junior year, Shenault wasn’t able to do any conditioning until June. Four games in — right when he started to feel like himself again, right when he was feeling like that Heisman candidate again — Shenault suffered a hernia injury against Arizona State. He’s still pissed about how this went down. The player trying to tackle him, he says, suddenly started backpedaling because he was apparently afraid to get trucked. Thus, when someone else stormed in, Shenault’s body was twisted into an awkward position.

If that player in retreat mode tried tackling him normally? “I would’ve been fine,” he says.

Instead, Shenault rolled onto his stomach in pain. He tried to play the next drive but could barely move.

An ultrasound revealed a tear to his core and, again, he cried.

Every time he coughed or sneezed or laughed, he hurt all over. He couldn’t even go to the bathroom. Further, nobody at Colorado informed Shenault that surgery would be for the best. They believed the hernia would heal on its own and, obviously, this tough-as-nails kid was going to play ASAP. Shenault sat out three games, returned and the tear proved to be much worse than anyone imagined. All he did was make it worse.. and worse… and worse… right into his pre-Combine training.

Finally, on the Friday before the NFL Combine, Shenault saw the renowned “Crotch Doc” in Philadelphia — the same savant who solved Damar Hamlin’s issues at Pitt — and discovered that surgery was needed. Not only was the one side torn, but now the other side was starting to tear because he had waited so long to get this checked out. One wrong move, the doctor told him, and he could rip the muscle right off the bone on both sides.

Shenault ran the 40-yard dash at the Combine anyways. Against everyone’s advice, he lined up and ran a subpar 4.59.

He had to compete.

“I probably would’ve gotten drafted higher if I didn’t run the 40,” Shenault says. “But I don’t care. If I’m healthy? If I’m able to train healthy? I’m easily a 4.4 guy. … After I ran the 40, I was like, ‘Yeah, I probably shouldn’t have ran that. That’s probably going to hurt me.’

He got surgery on March 3 and you know what happened next. The Covid-19 pandemic slammed America. Rudy Gobert touched those mics, sports shut down, life shut down, we were all forced to binge Tiger King and Shenault couldn’t even rehab with a trainer. He was forced to inch back to health completely on his own. Jacksonville made him the 42nd overall pick but Shenault certainly has not forgotten that eight other wide receivers were taken ahead of him.

As injuries lingered into his rookie season, Shenault still flashed. He managed 58 catches for 600 yards with five touchdowns.

And once OTAs hit this 2021 offseason, the lights finally flickered on.

He could cut. He could move. He was back to destroying tacklers. He was himself, as a player, for the first time since entering that Heisman conversation in 2018.

Laviska Shenault Jr. has finally realized one other thing, too: He has busted out of that shell.

What happened on Loop 12 is not replaying in his mind but he’s also not running from that memory.

Shenault has found a way to cope.

“If I’m thinking about something that’s not uplifting,” he says. “I try to get uplifted.”

The best way to get uplifted, he learned, was by stepping out of that seclusion.

His girlfriend helps. She’s an extrovert. She has a “complete opposite” personality, he says, which is exactly what he needed. He’s also living a few houses down from fellow Jags receiver DJ Chark. You couldn’t ask for a better role model to spend free time with. Chark has faced down his own demons, as he explained to Go Long in December. They’ve shared serious conversations about that trauma — Shenault isn’t afraid to open up to him. Still, the fast friends more so make a point to keep it light. And fun. And they’re both kids at heart.

Chark laughs that Shenault comes from that “TikTok generation.”

Whereas he’s more of a Pac-Sun guy himself, he says Shenault ponies up for designer clothes.

As a player, Chark says Shenault is “like a running back” with the ball in his hands.

And he acknowledges this reckless abandon is all a reflection of Shenault’s past.

“The NFL makes you grow up and learn who you are,” Chark says. “Moving out here to Jacksonville by himself. He had to figure out who he was and become the man of his house. He has embraced it all. And when you embrace things like that, you have more confidence in who you are. And he’s definitely showing his confidence. He’s a guy that I can hold accountable and will hold me accountable as well. Going into his second year, it showed that he’s getting more confident and more comfortable in everything he does.”

“He’s a very tough guy and plays that way. He’s very confident in himself, and he plays that way.”

Now, Shenault vows to act like a big kid until he’s 40. At the same time, he believes he’s more disciplined than ever. He doesn’t do much of anything other than practice, hang with Chark, sleep, practice, repeat. He enjoys basketball in the offseason. And he’ll typically watch whatever shows his girlfriend is into — usually Bob’s Burgers or Modern Family. When he is able to snare the remote, he’ll hot-route to Martin.

Or a Marvel movie. He loves Marvel.

“They don’t call me ‘Hulk Viska’ for no reason,” he says.

You bet Shenault loves the storyline behind The Incredible Hulk, how Dr. Bruce Banner can transform into this massive, green monster with superhuman strength. He sees himself in that character. His own alter ego, “Hulk Viska,” allows him to channel all raw emotions inside.

“I kind of live my life that way,” he says.

You won’t find many specimens like this at receiver or running back and that’s how he views himself — a blend of two positions. The last time Shenault measured his body fat percentage, it was 3.9 percent. He’s always around 4 or 5 percent. Never, ever more than 5. He can eat pretty much whatever he wants — Oatmeal Cream Pies, chips, cookies — without adding weight. Those genes are special. He’s still that kid who woke up at 4 a.m. to train, too.

The ripped 6-foot-2, 226-pounder before you is forever ripped.

He’ll now treat NFL Sundays like “Sideline Kill.”

To him, it’s simple: What’s there to be so afraid of? He will bring the pain to you.

“When it comes to the physicalness, a lot of dudes don’t want to be that physical,” Shenault says. “For me, it’s easy to be more physical. It’s less stressful. If you’re bringing the boom, you’re on the winning side of it.”

And when it comes to receiver, he’s shooting for a combo of Jarvis Landry (“because of his ‘dog’ mentality”) and Julio Jones (“he’s crazy athletic”) and Larry Fitzgerald (“how disciplined he is”). Not that he’s trying to be a traditional receiver. Call him whatever you want. This roaming mismatch is “trying to go crazy” in 2021.

These first two games have not gone according to plan, but if anyone’s freaking out in Jacksonville, Laviska Shenault Jr. certainly is not. He’s seen far worse things in life than an 0-2 start.

He’s come a long, long way from collapsing on his bed the night of July 17, 2009.

Shenault also knows this: The sun will always rise in the morning.