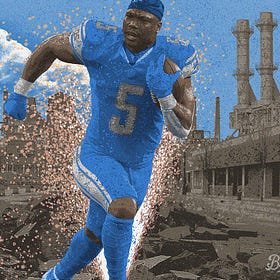

'I'm a sick f--k:' Why Al-Quadin Muhammad is the missing piece for the Detroit Lions

He's the menace out to kill quarterbacks. Go Long gets to know the pass rusher who was always meant to play for Dan Campbell in Allen Park. He has a lot to say.

ALLEN PARK, Mich. — When Al-Quadin Muhammad left the couch, flew to Michigan and stepped inside this Detroit Lions facility for the first time in October 2024, he felt certifiably rejuvenated.

This was his last shot. There were no guarantees on the practice squad. He was one of many defensive reinforcements ushered into town. A crew that’d later be dubbed the “northern savages” by Dan Campbell.

Muhammad studied the roster and his eyes widened. He relished the opportunity to face one of the best offensive lines in the NFL. He looked at the positives of life on the p-squad. I still get to do 1 on 1’s, he told himself. I still get to practice with the team. And then, his position coach served as a virtual bull fighter waving a muleta. Terrell Williams instructed Muhammad to practice like he’s trying to take somebody’s spot. Muhammad was much obliged. The pads came on and he took aim at the baddest man in the whole damn town: Penei Sewell.

This was the player Campbell declared the best player on the entire team.

Muhammad lined up across from No. 58 as much as possible and treated each scout-team rep as if it was third and 12 in the Super Bowl.

“That is my game. That was my interview,” Muhammad says. “I’m going 100 miles per hour.”

Sewell was not pleased.

Sewell, let’s remember, is a 6-foot-5, 335-pounder from the island of Malaeimi who escaped tsunamis as a child, mowed his family’s lawn with a handheld machete, tackled trees at age 7 for fun and — once he made it stateside? — concussed one poor sap in a game of “sharks and minnows” on the football field. Sewell looked us dead in the eye to insist (multiple times) that he’d die on a football field. In sum, he’s in the 99th percentile of pro athletes you do not irritate. Yet on what’s affectionately known as “Fast Friday” around the NFL, the typically tranquil final practice day, Muhammad went HAM.

The two nearly threw punches. Teammates stepped in.

“It came close. Came close,” Muhammad repeats. “There were some words. We stopped practice. He understands. He gets it. And that’s my boy. But that’s what you want! When I came here, I said this is the perfect situation.”

Go Long is your home for longform. Miss our latest column on Dan Campbell & the Browns? It’s right here for our subscribers.

Muhammad was vaulted to the active roster, carved out a role and is now sharpening himself into this contender’s missing piece.

Losing Aidan Hutchinson proved to be a death blow for the ‘24 Lions. Last season was a matter of week-to-week survival on defense. Thus, the clamoring for GM Brad Holmes and Campbell to acquire another pass rusher was loud. All offseason. Maxx Crosby! Trey Hendrickson! Myles Garrett! All pipe dreams were exhausted by the fan base. Yet, the Lions didn’t even re-sign ZaDarius Smith because the Lions believed they had answers in-house all along. When Marcus Davenport landed on IR with a chest injury, in stepped the 30-year-old Muhammad.

An opportunity he’s been preparing for his entire life.

This is the ultimate convergence of (maniacal) journeyman and (cutthroat) ecosystem.

Football’s gravitational force brought these two parties together because Al-Quadin Muhammad is the crystal-clear reflection of everything Campbell craves in a football player. After Detroit’s 38-30 win in Baltimore, the coach gave his defensive end a game ball. Fingers taped up, Muhammad cradled that football as if it was a newborn child. Teammates shouted “Speech!” and Muhammad did not disappoint. First, he thanked the entire organization because one year prior he was “on the couch.”

He then held the football up for effect. “When you get a fucking opportunity,” he said, “you make sure you take advantage of it.”

Truth us, this sport should’ve planted Muhammad on that couch for good countless times. Instead, Muhammad only grew stronger.

Over time, he’s heard coaches and scouts and media members all reference his age.

Nothing pisses him off more.

“You don’t know how I take care of my body,” Muhammad says. “You don’t know how I train. You don’t know what my day-to-day looks like. I don’t only have things to prove to myself, but everybody that says, ‘Oh, he’s 30.’ What the fuck does that mean? I should be better, right? Been around. Experienced more.

“I always remember the things I went through and understand the journey, understand my why.”

He heard all noise all offseason that Detroit needed a pass rusher and fully admits, “that shit fuels me.” Muhammad implores all of us to watch the tape. Through the Lions’ 4-2 start, he’s up to 4.5 sacks, 4 TFLs, nine QB hits and 11 pressures.

More than pure anger, he’s motivated by the Lions’ belief. When Campbell assured the masses that the Lions were perfectly fine on the D-Line, he took that to heart.

“It’s my job to make him right. Back him up,” Muhammad says. “They’ve got families to feed. They’re putting their jobs on the line. I’ve got to make them right. I take it personally.”

Suspensions in college. Suspensions in the pros.

GMs he claims did him wrong. Organizations that don’t prioritize winning.

Bringing a psychotic energy to gamedays.

Seated here in his locker, a “JUNGLE” tattoo inscribed across his chest, Muhammad opens up about it all.

“To be honest,” he says, smiling, “I have a unique story.”

That tattoo is a reference to his upbringing. Growing up in Newark, N.J., was rough and, well, Muhammad leaves it at that. The No. 1 lesson he took as a child was from his mother, a former track star. Mom never let him quit anything. If you start something, you finish it. Period. Words that still echo through his mind today.

When Pastor Catholic closed down his freshman year of high school, Muhammad attended renowned Don Bosco Prep. Coached by current Jacksonville Jaguars defensive coordinator Anthony Campanelli, he blossomed into the state’s No. 1 recruit. Muhammad collected roughly 30 scholarship offers, played in the prestigious U.S. Army All-American Bowl and chose the University of Miami. NFL glory felt like his destiny.

And before playing one snap of college football, his world turned upside down.

Muhammad had a son.

Inform him that having a child is jarring for a man in his 30s — let alone 17 years old — and Muhammad cuts in. He wasn’t petrified. He didn’t panic. In this defining moment? He genuinely embraced the balance of football and fatherhood.

“Some people look at things that happen to them in life,” Muhammad says, “and they look at it like, ‘Damn, I’m young! Damn, I’m this. Damn, I’m that.’ Me personally I look at it like, ‘Nah, I’ve got to make it.’ So when I’m practicing in college — my son was already born. This is a grown-man business for me. And it’s like ‘Y’all doing this for fun.’ I’m having fun doing it. But this is a little bit more personal for me. This is a different vibe.

“I’ve got to take care of my son. Anybody in front of me is trying to take food off of my table.”

Each drill felt like life and death. He needed to secure his baby’s future.

Not that college football went swimmingly… far from it.

This career should’ve combusted before he received his first NFL paycheck.

In September 2014, Muhammad was suspended for a semester after an off-campus fight that left his roommate with a broken nose. Little did anyone know what sparked the scuffle. Muhammad says his roommate knocked over his 2-year-old son down. The university itself levied the punishment, banning Muhammad from taking classes and playing football. Any Dad with any pride, he knows, would’ve done the exact same thing. “I whooped his ass,” he says. “I mean, it’s my son.”

Bad turned to worse that fall when the 19-year-old met a 25-year-old woman at a South Beach night club who — according to police — demanded $800 for sex upon returning to Muhammad’s apartment. Muhammad told her he wouldn’t be paying for anything and asked her to leave. He had zero knowledge this was a prostitute. That’s when the woman started throwing objects at him. After exiting the apartment, per reports, she then broke two front windows with one of her heels in an attempt to re-enter.

Muhammad exited the back door and cooperated fully with officers in the street.

He didn’t do anything wrong. This is also a night he’d like to forget forever considering he’s now in a serious relationship.

Nonetheless, the nightmare episode produced more embarrassing headlines.

After leading the Hurricanes in TFLs (8.5) and sacks (five) in the 2015 season, Muhammad was then kicked off the team before the 2016 season began for ties to a local luxury rental car agency. “The stuff I got in trouble for in college?” he adds, “these kids are getting that in NIL.” True, the current landscape of college football makes such punishment look downright silly in retrospect. But in the moment? His name was officially stained in the public eye.

His spirit could’ve been broken.

But, again, he cites his mental wiring.

“People could point the finger and say, ‘Oh, it’s their fault,’” Muhammad says. “Part of being a man is — however the chips may fall — you take it head-on. And that’s me. Me personally? I don’t really give a fuck how anybody thinks, how anybody feels, how you may view me, all of that. I don’t care if my name is being blown up, if I get the credit, if I don’t get the credit. At the end of the day, I want to be out there doing what I love to do and competing and proving people wrong in silence. A lot of people are rah-rah-rah-rah. My coaches and everybody will tell you, I don’t say too much. I just go work.”

All fine and good. He still had zero clue if he’d even get drafted.

His name carried baggage. He didn’t have much film.

Miami’s coach, Mark Richt, believed Muhammad deserved a second chance and vouched for him to NFL teams. In the spring of 2017, the New Orleans Saints selected him with the 196th overall pick. His Saints career lasted all of 24 defensive snaps in four games. He registered one tackle. Muhammad knows he was (extremely) raw. But he also knows one of the team’s position coaches was keeping an eye on him all season. Dan Campbell had his tight ends blasting 1 on 1 into the defensive ends during practice.

On to the Indianapolis Colts, Muhammad gradually developed into a starter. Oh, there were hiccups. Take the time he was ejected from a Thursday Night Football game vs. Tennessee after slugging offensive tackle Ty Sambrailo with a mean right hook. But this is the spunk, the bite, the habitual line-stepping a defense should crave in the right dosage. In 2021, Muhammad was able to harness all energy into a breakout campaign: 48 tackles, six sacks, 13 QB hits, one FF.

Life is obviously good for all involved with the Colts at the moment. They’re 5-1. Maligned GM Chris Ballard is in the midst of his finest season.

Memories of this team, however, still light a fire inside Muhammad.

He spent two different stints with the club (2018- ’21) and 2023 with a Bears season in-between.

Ballard was nice enough to reach out via text recently to tell Muhammad he’s proud of him. Recalling the exchange, it doesn’t appear as if the veteran wants anything to do with such pleasantries. “Just because somebody tells you something,” he begins. “it doesn’t make them right.” Muhammad cannot forget Ballard telling him he was too old, too stiff to keep around on the roster.

He claims he’s not bitter by how his time ended with the Colts.

He’s certainly motivated.

“I know he knows,” Muhammad says. “You fucked up. I know you really know now. The moment is never too big for me. The opportunity is never too big for me. I’m always trying to find an edge. I’m always looking for ways to win. I’m so competitive. I want the game to be on the line. I want the defense on the field. Why not me? I have that mentality.”

The Colts moved on. From January ‘24 to August ‘24, he was unemployed.

Muhammad didn’t help his cause with a six-game suspension for taking performance enhancing drugs. He tells me it was related to intravenous therapy. Into the ’24 season, he still needed to serve one game which rendered him damaged goods in the eyes of many NFL teams. There was nothing he could do but wait… and wait… and hope somebody saw something in him. Life on that proverbial “couch” wasn’t wasted. Muhammad trained every day and made a point to get his investments in order. He spent the month of August with the Dallas Cowboys and was released. “Nobody,” he admits, “really wanted to touch me.”

When injuries naturally shelved defensive linemen around the league, he got some looks.

Miami, Arizona and Houston all worked out Muhammad.

Detroit was his fourth visit. Off a bye week, the Lions were searching for any help rushing the passer. Muhammad realized this was likely his last chance. So, no. When the Lions added him to the practice squad, he did not intend to go through the motions. This was a title contender in dire need of bite on defense. Each rep against Sewell was a chance to prove he belonged on Sundays.

After one month, the Lions bumped Muhammad up to the 53-man roster.

Outsiders were surprised to see the chiseled 6-foot-3, 250-pounder harass quarterbacks. He supplied the key third-down sack in what was essentially an NFC North title vs. Minnesota. Afterward, one of his heartfelt postgame interviews went viral. At his side is his son: Al-Quadin Jr. After Dad says his son motivates him in countless ways, Al-Quadin Jr. chimes in. “I’m just happy that he’s a dawg,” his son says. “We pray every night. I love this guy. I love him. This is my Dad. We’re going big.”

Muhammad expected to make such plays because Muhammad is still that kid from college who doesn’t give a bleep what anyone thinks.

He knows this is easily one of the most valuable intangibles an NFL pro can possess.

In this profession, your employer’s constantly seeking a younger, cheaper replacement.

“The thing that people have to understand about the NFL is they forget about people so fast,” Muhammad says. “I’m a little fucked-up mentally with how I view this thing. There’s a draft every year for a reason. But the thing is, when young guys come in, there’s a learning period. There’s an acclimation period.”

Some rookies are mature enough to weather the NFL storm. Most are not.

Muhammad views them all as a threat to his livelihood.

“In my mind,” he continues, “I’m saying to myself, ‘The only way you could bring a motherfucker in that could take my job if he’s training as hard as me. I don’t drink. I don’t smoke. I don’t do drugs at all. So for me personally, I’m saying to myself, ‘This motherfucker has got to be…’”

Speaking fast, his words trail off. He says he’s constantly evaluating everything and everyone around him.

“You might be better than me Day 1, Day 2, Day 3. But after a while, your body starts saying this or that. So mentally, physically you’ve got to be where I’m at.”

His face stretches into a sinister smile, essentially begging anyone to try him.

He’s always been the same competitor.

“I’m a sick fuck.”

Sick in terms of his diet. He eats the same meals every day in numbing monotony. For breakfast, he’ll down the same egg whites with spinach. Often with mushrooms, onions, tomatoes blended in and an avocado on the side. To drink, it’s water with lemon or a Pedialyte. Sick in terms of how he trains. During the offseason, he prefers to work with his own trainers to follow his own obsessive routine. By 6 a.m., he hits the field. Then, he lifts weights. He’ll lift — hard — five times a week. Sometimes, six. All while mixing in boxing classes, yoga, Pilates and various jump rope routines. Sick in that he’s now the first player to step inside this building. He’ll wake up at 5:30 and immediately drive to the team’s complex in Allen Park to lift, get treatment, rifle through clips on his tablet. (“I work my ass off. I study my ass off. I watch a lot of film and I’m my biggest critic.”)

This is who he’s always been. Nothing ever changed. Football’s a business and the Colts always seemed to always have a higher draft pick or more lucrative veteran keeping him on the sideline. Even in Detroit, it took an avalanche of injuries for Muhammad to sniff the field.

All along, Muhammad viewed himself as a starter.

Such brazen belief is the only horcrux an NFL veteran needs to thrive well past their expiration date.

Politics can drag a team down. It’s why so many players gushed over Mike Vrabel, praising his merit-based approach. Those who practiced well were promoted. Those who struggled were demoted. He trusted his eyes, not a resume. Muhammad played only seven defensive snaps in the Lions’ Week 1 loss at Lambeau Field. The Lions even had him covering kicks. But he never took it personal because he knew that Campbell and the entire staff appreciated his game. All camp, he trained at defensive end, the 3-tech and 4I positions.

“You just pray to God that you get the opportunity and then when you get the opportunity and you get out there?”

He snaps his fingers.

“You’ve got to put it on tape.”

Since then, he has averaged 29 snaps per game. The Baltimore game was his coming-out party.

On one second-and-goal play at Baltimore, all that was missing was the ominous piano. Muhammad went full Michael Myers in tomahawking his arms through left tackle Ronnie Stanley to gain the edge and chase down quarterback Lamar Jackson from the blind side for a sack. Next, from the other side, he discarded a tight end to stare down the QB mano a mano — a predicament that typically doesn’t end well for defenders. Muhammad didn’t fall for any trickery in wrapping up Jackson for Sack No. 2. And then his play of the night came with less than 5 minutes to go and Detroit clinging to a 31-24 lead. On third and 12, it appears Muhammad’s been washed out of the play as Jackson steps up into the pocket with nothing but green grass in front of him.

But the vet doesn’t quit. Muhammad redirects upfield and Superman-lunges horizontally to corral the two-time MVP for a meager 3-yard gain.

The Ravens were forced to punt. The Lions iced a win with one more touchdown.

We all see the damage, but what else goes into being a self-described, uh, “sick fuck?” In simplest terms, he says it’s a refusal to be broken. Nine seasons in, it still irritates him when sixth-round pick is attached to his name like a preexisting medical condition. There’s a healthy anger to his voice.

“That ain’t my value,” he says. “My value is when I chase guys down the field and I’m running out of the stack and I’m flying around. That’s what people don’t see. The little things. The hustle. The motor. You can’t put a price on that. A lot of people are talented. But mentally do they want to chase a guy 60 yards down the field? Every play? So it’s just having the will. Yeah, I’m 30. But with being 30 years old, that comes with trials and error and it also comes with wisdom. And also learning from your mistakes.”

Many people experience adversity in life and lament “this happened to me.”

His logic is different.

“No, no, this happened for me,” he says. “Ain’t no shit that happened to me. It happened for me.”

All of it — college fights to those four tryouts — led to a perfect union.

He found an organization that covets such a motor and lets him hunt. Campbell and Holmes have always been searching for a specific DNA strand.

Detroit identified the animal within because Detroit isn’t like other teams. Take those Cowboys. Jerry’s World feels more like a museum than a football facility with tours passing by nonstop. The rot is real. Jones sets a corporate tone for all execs, all scouts, all coaches involved with the organization. Very quickly, you realize that winning football games is a secondary concern. No wonder so many players on the fringe get lost.

Muhammad never felt fully understood in Big D.

“They like names,” Muhammad says. “Dan Campbell watches tape. It’s different. These coaches watch tape.”

His voice speeds up again.

“This place? We don’t give a fuck about what you did. They don’t care how you got here. You do what you’re supposed to do and you compete? They’re going to learn your name.”

Kacy Rodgers took over as the Lions’ defensive line coach last spring and was immediately impressed by Muhammad’s football IQ. That’s what allows him to stalk along the line, position to position, in search of a juicy mismatch. And when the ball’s snapped? He’s all gas, no brakes. Rodgers cites a play vs. Cincinnati in which Muhammad chased Jake Browning across the field.

“That’s the way he is in practice,” Rodgers says. “High energy, high motor. He’s always 100 miles an hour.”

Rodgers has coached defensive linemen in college and the pros since 1994.

Too many pass rushers, he explains, get stopped initially and concede defeat. Not Muhammad. He “outworks” linemen. Up close, Rodgers sees how this all is a direct extension of his NFL journey. Linemen think they’ve got Muhammad blocked up and he drives harder. He busts free.

“He’s had adversity,” Rodgers says. “He plays like every play is his last because he’s been where they call you in and say, ‘We don’t have a place for you.’ So he plays with a chip on his shoulder. He feels like he’s got something to prove. No one in the outside world thought there was another rusher in the building. So he’s saying to himself, ‘What am I? Chopped liver? Then, I was sitting on the couch. This organization gave me a chance.’ He’s trying to make the most of his moment.”

Muhammad promises he’s not close to finished. He’s still driven by his son.

Al-Quadin Jr. is 13 years old now. He doesn’t live here in Michigan, but he visits often.

It’s as true now as it was in Coral Gables as a college player. Dad views anybody across the line of scrimmage as someone who’s trying to prevent him from putting food on the table.

Adds Muhammad: “I’m still not full.”

So, bring on the national spotlight. Muhammad views all of these primetime games as a chance to reintroduce himself to the country. This Monday night, the Lions will host the 5-1 Tampa Bay Buccaneers. Attention will naturally veer toward Hutchinson and it’ll be incumbent upon someone else along this Lions front to wrangle MVP frontrunner Baker Mayfield. It’s not complicated. If the Lions are able to generate a lethal pass rush, there’s a good chance they’ll reach the Super Bowl.

Al-Quadin Muhammad views himself as that integral variable, too. The Darwinian nature of pro football brought him to Campbell’s world.

He doesn’t care what he’s asked to do on a football field. He vows to be a force of mayhem wherever coaches play him.

He could talk forever. He can’t help it. He relishes being the bad guy lurking around that corner with wrath in his heart.

Finally, the world’s about to learn who he is.

“I don’t flinch. I don’t blink,” he says. “At the end of the day I look at it like, ‘Put it in front of me and I’ll figure it out.’ It may not be Play 1. It may be the first quarter. It may be third quarter. I’m going to impact the game some way somehow.

“That’s who I am.”

Lions profiles past:

The Full Monty: Why Detroit Lions RB David Montgomery runs so damn hard

ALLEN PARK, Mich. — The running back who shrouds himself in mystery is coated in tattoos and battle scars. A crucifix behind one ear. The image of teeth and lips smiling between his thumb and index finger with the message: “Why so serious?” Bruises and scabs blot both knees. And as David Montgomery digs at one gash on his le…

Man in the mirror: Alim McNeill explains the Detroit Lions

ALLEN PARK, Mich. — The stench is gone. After three full seasons of WWE-like draft celebrations from the general manager and more damage to the vocal chords of the head coach than we could possibly imagine, it’s Morning in America. The Detroit Lions are on the cusp of winning their second playoff game since 1957.

ICYMI, this week:

Tyler, just wanted to let you know I this your work on this site is outstanding. Happy to be a subscriber and look forward to more great stuff.

Subscribed to read this post, excited for the year of this type of journalism