'See me in the fourth quarter:' Leroy Hoard wanted to break you

He wasn't a 300-pound sledgehammer. It only seemed that way. Here's the transcript of our conversation with former NFL running back Leroy Hoard.

Greetings, all.

From seeing dead bodies in the 9th Ward of New Orleans to Ann Arbor, Mich., to taking on linebackers with bad intentions, Leroy Hoard most certainly was bred to thrive in a violent NFL.

Loved catching up again with the ex-Brown, ex-Viking great on the Go Long Pod.

Writing about those Cleveland Browns this week got me thinking that a Zoom with Hoard was long overdue. This time? We explore his career… one that took a toll on body and mind. Hoard spent six seasons with the Browns, four with the Vikings and enjoyed a quick cup of coffee with the Panthers in-between. You didn’t want to cross Hoard. Where he’s from? “If you come at me in a disrespectful way,” Hoard details, “you’re supposed to get a two piece and a soda.”

Today, Hoard is a fixture down in South Florida sports radio.

The full transcript of our conversation is below.

Here’s the audio/video:

Thank you for growing our community at Go Long.

Have the Substack app? Download today to access all stories, all podcasts and join Live videos:

Dunne: So you have a very good hockey team down there in Florida. Have you been taking in the Florida Panthers? Riding high to the Stanley Cup?

Hoard: Absolutely. I mean, probably the best thing about it was, they took the Stanley Cup to the Atlantic Ocean, which I guarantee has never happened before.

Dunne: Leroy Hoard. This has been too long. I feel terrible that it’s been three, four years since we caught up on the Go Long Pod, because when we did it (here and here) I’m like, “Oh my God, we have to get LEE-roy back,” and that’s how you say it. We’ve got to get LUH-Roy Butler on here. You have the emphasis on the LEE, so maybe we’ll get you two together sometime.

Hoard: Yeah, I think we played against each other.

Dunne: Those Vikings-Packers games were some battles.

Hoard: Yep, absolutely.

Dunne: Visions of 44 snatching souls. You epitomized the glory era of pro football. I know we’re all biased with what we grew up on, but for me it’s the 1990s. You ran the ball how God intended running backs to run the ball: Downhill. A lot of Leroy Hoard coming at you — fast — but when you look back at your era, what do you think really did separate you from other backs of that time?

Hoard: I played hard but had a level of quickness and speed that people never associated with my game. They always associated power. And once you do that and then somebody runs away from you? You’re shocked. And I was able to play a long time without people ever truly realizing that, “Hey, I wasn’t that slow.” I just got this short-yardage moniker put on me. And so everybody just assumed he was a big bruiser, but I was only 220 pounds.

Dunne: The big shoulder pads is what did it, right? Monster shoulder pads.

Hoard: Right. Everybody thought I was so much bigger. And I remember when I got done with football, I was getting irritated by it and somebody said, “Man, I thought you were bigger.” I said, “Have you ever tried tackling me? How the hell would you know?” So it was just one of those things where people called me a fullback, but I never blocked. You deal with it. I got to the point in my career where if I have to prove to you what I can do on a football field then you don’t want me on your team, right? You should already know what I’m bringing to the table. And so I feel that same way in life. The more you have to prove what you’re capable of and not have evidence of it in what you do on your daily job — if people ask you that question and you haven't shown them enough — then they don’t want you there. That’s how I viewed it.

The most annoying thing about sports to me is that we want to blame a guy for all of our team’s failures. And there’s so many moving parts on a football field that one little teeny thing could go wrong and it could throw a whole play off. And I don’t think people understand that. They just look at, “Hey, the quarterback threw a pick.” Well, if the left tackle missed his block and the quarterback had to throw a ball in hopes that the wide receiver would get in that area and the wide receiver didn’t get in the area, things go wrong. And it’s not like basketball and baseball. In basketball, if I shoot 40 percent from three, I’m damn near a Hall of Famer. Baseball, if I bat .300. From a football perspective, we look at the other side of that. You’re failing 70 percent of the time and you’re failing 60 percent of the time. Because football is a 100 percent sport. You could win 55-10, you interview a coach after a game and he goes, “You know what we did OK, but we’ve got a lot of things to work on.” It’s a 100 percent sport.

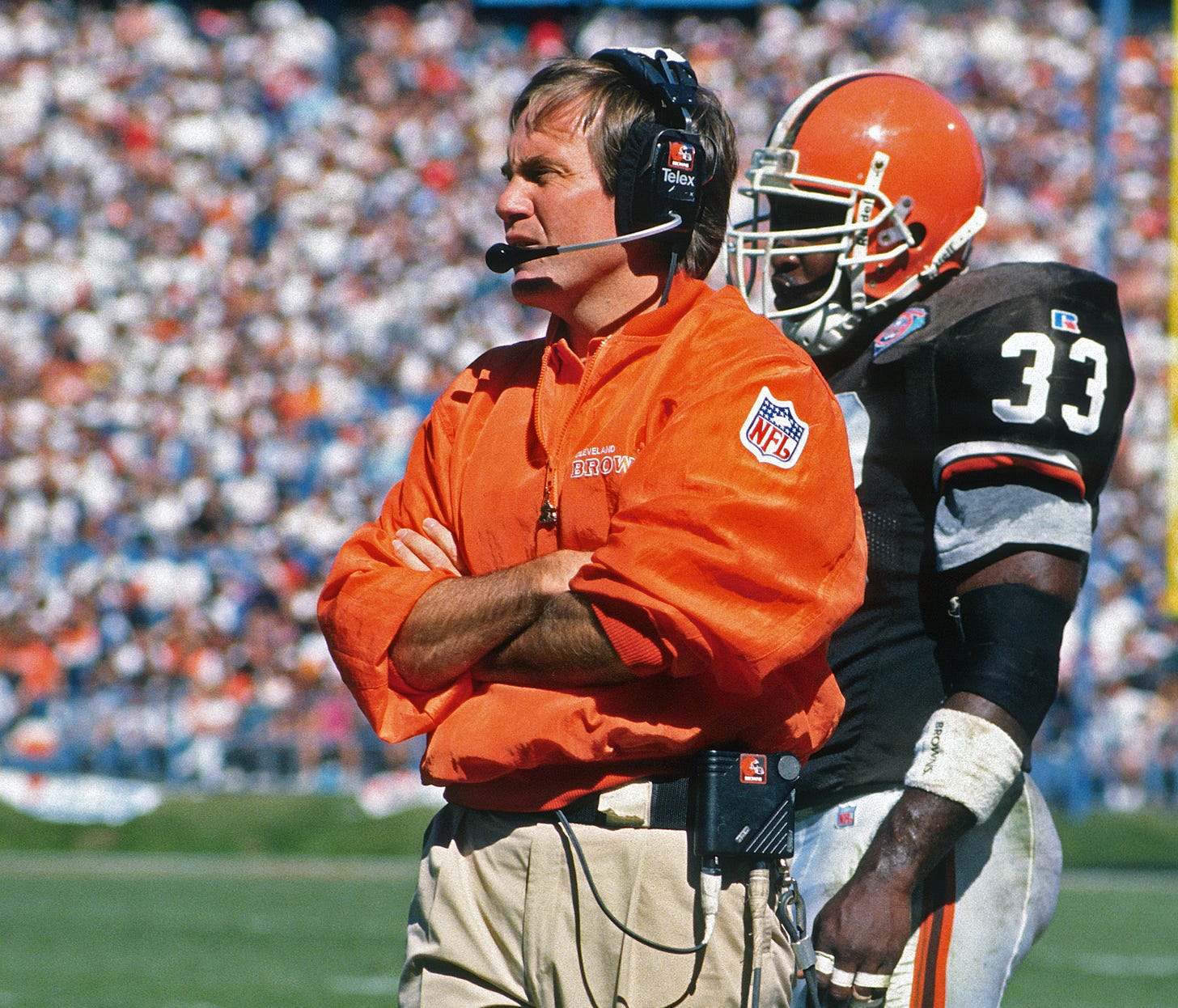

Fans don’t put it in perspective, but I think players can and players get to it. The only time players don’t is when the media pounds them on: “Well, why you only had this? Why you only had that?” I knew when I was playing, if you play running back for Bill Belichick, you’re going to have 30 carries one week and five the next week. Go look at his career and you have to learn how to handle all that stuff when people come to you and say, “Why did you only have five carries?” Nowadays, players will say, “Talk to the coach.” But back then it was like, “We’re winning.” If you got a problem, you think you could do more, go talk to the coach. But I’m not going back and forth with the media.

Dunne: That's a refreshing mindset because if I’m Leroy Hoard, I’m looking back to those ‘98 Vikings and I’m saying, “My God, if Gary Anderson just makes a kick we’re legends.”

Hoard: Going to the Super Bowl. And you know what? The thing that you learn in sports is that every time you go out there to perform, that missed field goal could be you. And so when you talk about it, you talk about it accordingly. I fumbled the ball a lot. I can’t really know when it cost me a game or I can tell you pretty much every time. It cost me one time against Ohio State, but it’s the worst feeling in the world. I wouldn’t wish it on anybody. I think because of me growing up in the Ninth Ward of New Orleans that I can take criticism. It doesn’t bother me. I remember a reporter asked me one time after a game: “Did you hear the fans booing you when you guys went in halftime?” I said, “I would’ve booed my ass, too.” We played like crap. You’ve got to be a big boy about it. You’re front and center. There’s 70,000 people watching you that parked their cars in the flat on Friday night to have a good tailgating spot, got hammered and ate too much food before kickoff even started. Got liquored up during the game. They want to see their team perform, right? And I would tell fans that, “Believe me when I tell you: it’s not for lack of effort.” Sometimes, things just don’t work out and you don’t know what to do to fix it and you’re miserable. You’re miserable. But here’s the other thing I learned. The world’s going to keep spinning whether you win by 20 or lose by 20 and you’re going to have another game next week. So is this bad game on this Sunday going to affect you next Sunday? So you put it in perspective.

Dunne: I’ve got to think that’s what sustained you through an entire decade, ‘90 to ’99, where you’re playing for the Cleveland Browns and your team moves to a new city. Fans are ripping apart the stadium. You’re there. It’s got to be a surreal scene. To Carolina, your career basically could have ended. To a Minnesota resurrection. You’re scoring touchdowns, you’re reeling off all these highlight runs and receptions. You’ve lived it all. But it is that mindset, right? You can’t wallow in self-pity or be soft-minded. You’ve got to be hard and — where you grew up? — that’s going to make you hard.

Hoard: Exactly. I would always tell people, “There ain’t nothing you got inside of you that could break me.” So start there. Everybody looks at me as a big guy. I’m probably 215 right now. I say, “You realize when I was in the huddle, I was the little guy.” So think of the mentality that I had to play with. So while you’re looking at me as a big guy, I had to go on the field and fight like hell like a little guy. And it’s just something about it. When we left Cleveland, I was, what, 25 years old? In two months, I lived in four cities. Because I went from Cleveland to Baltimore. In Baltimore, I bought a house and the builder had a deal. If you are not here in a year, we’ll buy it back from you. So it seemed like a good deal. I got moved to Carolina before the house was done, so I couldn’t even get my money back. I had to wait until the house was built. So there was that. Then I went to Carolina and Tim Biakabutuka got hurt. So I ended up in Carolina. They had a guy named Anthony Johnson. When they brought me in, here’s what they said: “We’re going to pay you a contract, but if Anthony Johnson works out, we’re going to move you again.” So I was there for a month. I signed a lease on Friday. On Monday, they told me that I was getting moved again and I had just put a deposit on an apartment and they wouldn’t give me the deposit back.

So now I already have a place in Florida. I still had my place in Cleveland. I had the place in Baltimore, then I had an apartment in Carolina. So then, I got to Minnesota on a Tuesday. On Sunday, I was the starting running back for the Minnesota Vikings. Now, if I could explain to people what that’s like, it’s as if I took everything that you had and then dropped you off in China and told you that you had to communicate, you had to learn, you had to figure it out, and your new job starts on Sunday. I knew no offense. The offense was totally different. The terminology was different. Everything was different. So I’m there every night trying to learn as much of the offense as I can because keep in mind, most of these guys have been doing it for a couple of years, or they had camp and they played five games, six games.

We play the Oakland Raiders in Oakland. And the first series of the game, they call a play. I’m like, “Cool, I know that.” Brad (Johnson) turns around and goes “Purple! Purple. Purple!” I’m like, “Brad, what does purple mean?!” I had no idea. So we’re watching the film of that game that went into overtime. We win the game. We watched the film the next day and all you could see is me in the backfield going like this. (Hands outstretched) Because I have no idea what anybody’s talking about. And that was the most terrifying football I’ve ever played in my life. Not Rose Bowls. Not playoff games. The most nervous I’ve ever been on a football field was that game with Minnesota, not having any idea of what to do and having to rely on a guy I just met to tell me what to do.

Dunne: You ran for 108 yards on 20 carries in an overtime win that game in “China.” Not too bad.

Hoard: It was muddy and rainy. I was cramping up because running in mud is tough. It is harder on your legs. Holy smokes.

Dunne: Oakland Alameda County Coliseum was the worst stadium in football.

Hoard: When they bussed you in, you went in jail buses because people were throwing stuff at you. So you had the cages on the windows.

Dunne: And I remember covering a game there as recently as 2016. You’re walking through the bowels of the stadium and there’s wires hanging from the ceiling. There’s leaks and rips. It looked like the thing was going to collapse at any moment. So take me back to the Ninth Ward in New Orleans. What was life really like for you then? We hear the stories from Tyrann Mathieu, Leonard Fournette, so many guys that have come through there. It makes you different.

Hoard: We all went to the same high school. So there’s arguments in New Orleans: “Who was the best running back? Leonard Fournette or Leroy?” I think he ran for like 4,000 yards in college. But I told them I ran for 1,500 yards and averaged 14 carries a game. I remember one game in high school, we were playing a team and I had 300 yards at halftime, and the coach told me I could go sit in the stands with my Mom.

Dunne: Did you go?

Hoard: Yeah. So what I would say is, is that growing up, that’s the real south. Some of the circumstances and situations you have to live through I’ve never experienced anywhere else that I’ve ever lived. And I would say to people: “Before you walk up on somebody, make sure a little bit about their background.” Because one of the things I hated about the NFL was it almost neutered your athletes. People can walk up to you any old kind way and not look at you as a man, but look at you as a football player knowing you ain’t going to do nothing. And I didn’t grow up like that. I grew up — if you come up to me as a man — I’m going to handle you like a man. If it is cordial, it’s cordial. But if you come at me in a disrespectful way, you’re supposed to get a two piece and a soda. You know? It took a lot of getting used to not be able to be a man in those situations.

You know damn well what people yell at athletes and what people say about athletes and about men. If you saw them in the street and you said something like that, you’ll get your ass beat. And so that was one of the things that I hated about. Other than that, I was fortunate to play football in three of the greatest places to play football: Michigan, Cleveland and Minnesota. I was the same football player at all three spots. Everywhere I played, nobody asked me to be anything other than what I was: “Go out there, make people miss, fight like hell, give me everything you got and we can work with that.” And from the time I left Michigan, until I got to Cleveland, until I went to Minnesota, I never had to change what type of player I was. And this is all through high school. So I was fortunate in that the adjustments that people have to make going from team to team, everybody looked at me and said, “Oh, we need a running back like that.” And so I never had to say, “What do you need me to do?”

Dunne: Third and 37. Run Leroy Run.

Hoard: Which is the craziest thing in the world because when Denny sent me out there, we were on our own five-yard line. He goes, “Just give us some room so we don’t have to punt out of the back of the end zone.” That was the whole idea behind it.

Dunne: What did you see in the Ninth Ward then? The real south? Is it a world we can’t comprehend?

Hoard: Once a week, there was a dead body under the bridge. Gunshots every night. My grandparents lived there for 50 years. So they knew everybody’s Mom. Their Mom’s Mom. Nobody messed with my grandparents. Me and my Mom and my sister, my brother lived across the street. My uncle lived in a house right next to us. So we were all pretty close. When you grow up in those situations, one thing you do appreciate and you understand is people doing what they have to do to survive. It’s a different world. People got a little hustle going. In the hood, somebody works on cars, somebody’s doing hair. That’s life down there. And so there were people selling drugs. And I would say my experience with drug dealers is a little bit different in that the drug dealers in the Ninth Ward who — keep in mind — my grandparents knew their Dads and their Moms, they would never let me get caught up in it. They say, “Hey man, you have a chance to get out of here.” So everybody in the Ninth Ward kept me away from it. “If you need something, don’t worry about it. You ain’t got to pay us back. Go do this.”

So I have a different understanding when people don’t have. And some of the things they have to do to make ends meet. And so I don’t talk about it like it makes me harder. I don’t talk about it like I’m better than anybody or I had it harder than anybody. I just talk about it to let people know where I came from and how I got here. And sometimes it’s hard for people to comprehend how tough it was. When I was growing up, if somebody stole something, you would rather get caught by the person you stole it from than the cops because the cops was going to take it and then you were still going to be on the hook for stealing it. It was a different animal. We had the worst police force in the world when I was growing up. The cops were as crooked as the people. So the politicians were all crooked. Hey, when I went to Michigan, I got an absentee ballot for governor of Louisiana, and this is all you need to know about Louisiana. My two choices for governor were Edwin Edwards, who had already been kicked out of office for embezzling money, but for some reason he got to run again. And you know who he was running against? David Duke. So that’s just a snippet of what goes on in Louisiana. Now, kudos to the citizens of Louisiana because you took the crook over the morally corrupt, and guess what he did? Stole money and they had to throw him in jail.

Dunne: Democracy in action, everyone.

Hoard: That was my two choices in a democracy.

Dunne: All of this is going to help you as a running back taking on Greg Lloyd, Levon Kirkland in the old school AFC Central somehow. How does it make you as a 90s running back?

Hoard: There’s two things that happen when you play football in the NFL, depending on what position. You play running back, you’re going to get hit on every play. They’re going to chicken-wing you when you’re walking by — give you a little chicken wing, give you a little bump. When you get tackled, they’re going to mush you because they’re going to try to break you. My background is, “You ain’t going to break me. You’re not going to break me.” And I would always say, “See me in the fourth quarter.” Because if you can keep hitting me like this in the fourth quarter, I’m going to shake your hand. And in 10 years, it never happened. In 10 years, everybody got tired of hitting me. And they give you that look like, “You’re still going?” Yep. Because that’s what this job is.

Dunne: You remember that look? You saw it in somebody’s eyes?

Hoard: All the time! They look just look at you crazy. Here’s what people don’t understand. Say I’m 220 pounds. I run a seam route and I’m running and the linebacker’s covering me and I’ve got decent speed. I’m not Eric Metcalf fast, but I can move a little bit. And I look and 99 is running with me. That’s Levon Kirkland. Now, I don’t think people understand Levon Kirkland was 295 pounds. I could not run away from him.

Dunne: We’ve had him on the pod — 295 and he could run.

Hoard: As a middle linebacker. What’s the difference between college and the NFL? Add 30 pounds to whatever position you’re playing against, right? Because you understand running backs are pretty consistent from college to the NFL. One might be faster or quicker, but the range of size of running backs has always been consistent throughout the history of football. You have some scat backs, you have some Eric Metcalfs, you have some guys that are 215, 220, which is probably ideal. And then you have your big people. You might have a Christian Okoye. You’ve got Derrick Henry right now. So you have those guys. It’s never changed. Every time you open up a roster, you’re going to see the same sized guys playing running back. Maybe more skilled, maybe a little faster, but the same size.

But on defense? Whatever you went against in college, add 30 pounds and take about two-tenths off their 40. So you might have an outside rush end or a linebacker that in college he was 240 and ran like a 4.6. OK, now that guy’s 265, 270 and run a 4.4, a 4.5. So yeah, it’s mind-blowing to stand in a huddle with offensive linemen. I played with Orlando Brown, “Zeus.” Tony Jones. When I was in college, I played with Greg Skrepenak, Jumbo Elliot, Steve Everitt. So I always had big guys. When I was in Minnesota, the right side of our offensive line averaged 345. I used to watch offensive lineman and defensive lineman have dunk contests. So when people talk about a guy that “sucks” in the NFL, I know how athletic these guys are and I’ve seen it. And so it's never going to be a lack of athleticism that a guy that gets to that point doesn’t make it.

Dunne: What’s the most memorable collision that you had in this crazy world? I think at one point you were hospitalized with a concussion.

Hoard: You remember the story Bill Belichick told when they were talking about concussions? And he said, “I had a guy who was healthy and I sat him out an extra week.” It was me. And here’s the kicker. Big, strong, tough Leroy. You know how I got knocked out? I was running down on kickoff. Now keep in mind, I’m not a tackler. I just hit people and hope they fall down. Everybody had to play special teams. So I’m hauling ass. I’m the first one down there. I’m going and knock this little-bitty kickoff returner out. I’m canceling him. He’s done. Now my form as a tackler was poor at best because, well, I’m not a tackler. So I turned my head just a little bit and he hit me right here, and I was in the hospital. Now that’s not the worst part of it. You know what the worst part of that is? He was the smallest guy in the NFL.

Dunne: Who was it?

Hoard: “Ice Cube,” Gerald McNeil. He played for the Browns before I got there. And then he went and played for the Oilers at the time. Now when I was in Minnesota and things get crazy. Because you have coaches that you catch a screen pass and here’s how screen pass works. You go under the kickout, back outside. The coaches: “Get under there, go back outside.” Well, I was kind of a cutback runner, and so I went under that and then I saw a little room and I turned to cut back. And the next thing you know, it felt like everybody was taking my picture. Out. Done. And then they come out and then let me tell you something. The test for a concussion back then, it was crazy. “What quarter is it?” I just look up at the board: “Third.” “What down is it?” I’m like, “Second.” I’m looking at it. Do you know who hit you? And at that point I said, “Not for nothing. But if I’d known that dude was going to hit me like that, I would’ve got the hell out of his way. No, I don’t know who hit me.”

Dunne: You’re good Leroy. Get back in there.

Hoard: Actually they held me out for the rest of the game. So I just think the whole concussion thing, we can put it on somebody. But I think everybody was ignorant to the facts about concussions. And when it’s everybody — even fans, even training staffs, coaches, doctors — there just wasn’t enough knowledge of what was really happening at that time. Because most people associate concussions with hits. That’s not what happens. What happens in a concussion is, you could get pushed from behind and get a concussion because it’s your brain being jarred in your skull.

Dunne: Sloshing around in there.

Hoard: Right. So that doesn’t necessarily come with a hit, but everybody thinks that.

Dunne: And I know you went through it, right? You dealt with the aftershock of brain trauma. Andre Waters, Dave Duerson, and Junior Seau — those suicides had an effect on you. Early 2000s, what did you go through?

Hoard: It’s one of those situations where you don’t know what’s wrong. There’s no guidance as to what direction you should take to get through it. So for example, one of the hardest things for me was I was so used to living in this world of accountability and a world of owning your mistakes and a world of conversation and being honest about what’s going on. And then you get into the real world and nobody believes that crap. Nobody. You ever call somebody, you ever say, “Hey man, I was expecting something here.” Nobody lives by what they expect athletes to live by. And I think I became a little bitter about that. I lived in a world that nobody could live in. So that was tough. My body had broken down to the point where I don’t think I could have played football even though teams called me for two years after I was done. Minnesota told me, “Just come back and if you only come back for the second half of the season, that’s fine.” After my last season, I played the last year with a torn rotator cuff. So the day after the season, I had shoulder surgery. Here’s the kicker. I was supposed to have knee surgery and I couldn’t have the knee surgery because I couldn’t walk on crutches. So I had the two months with the arm. Then when I could walk on crutches, I had knee surgery. I had to be on crutches for eight weeks with the knee surgery. By the time I was healthy, it was October.

I was banged up. I was confused. And then seeing all the other stuff going on, I started thinking, “Damn, am I crazy too?” Because I couldn’t understand what was going on. I couldn’t understand why everybody else wasn’t living by these set of rules that we were expected to live by. And so I think that was the hardest thing for me to get used to. The hardest thing was to go into the real world and realize that when it comes to how people treat their athletes, everybody’s a hypocrite. There’s no way you could live by those rules. You could even go as far as reporters and how they come after players and how they say, “Oh, you have to talk to us.” I was good with the media and all that, but I’d hold them accountable all the time. So the way it works, and here’s what people have to understand: You play a game, you go in the locker room, the coach talks for about five minutes, 10 minutes. And then the reporters can come in the locker room.

While you’re changing, while you’re showering or whatever, they’re waiting in front of your locker. So people would ask me questions and I’m like, “So you watched the whole game? You took notes during the game?” I said, “I haven’t watched any film. I haven’t had any opportunity to see what actually happened.” Because my only perspective of the game is through my eyes. I don’t know what’s going on, on either side of the ball. I don’t know any of that. And I go, “You’re college educated. You get paid to be a journalist. And that’s the best question you could come up with.” But I did it because, “Wait, if you’re going to hold me accountable and if I fumble and I’ve got to answer questions about letting the team down and all this, I’m not going to let you come in here and just say anything.” So I never had a problem with anybody unless they… I would ask them, “What are you trying to accomplish here?” And then they would always hide behind: “Well, we’re just trying to get information so we can share that with the public.” And what happens is they use that so much that now players use Twitter and Instagram because they don’t want to deal with it.

Dunne: I would’ve loved to have covered you after those games because you’re going to be real. You’re going to be authentic. Your emotions are going to be at an all-time high. That’s why I like being in a locker room right after a game because you’re not going to get sanitized bullshit from Leroy Hoard. You’re going to get something real. Even if you’re pissed off, it’s real.

Hoard: Here’s the problem with all that. Even if you answer questions real, and I would tell them, “You write what I say. I’ll tell you what I mean. You don’t have to guess. You don’t have to figure it out. So that when I see these quotes in the paper, I want ‘em to be this. Not what you think.” And so from that standpoint, I remember somebody asked me about when the team was moving to Baltimore. And keep in mind, the players have no idea what’s going on. The owner left. All the front office people were gone. The only people to answer for all this stuff were the players. And we had no idea what was going on. So I remember telling the reporter, I said, “Hey, this is all I know. I love it here. I would like to be here. But when your boss say, ‘Hey, your next check is going to be in Baltimore, guess where Leroy is going?’ I don’t know what to tell you.” Right? That’s real. That’s reality. And so people could take it however they want, but if I put you in that situation, you going just come home and say, “Honey, we got to move to Baltimore.” And that’s it.

Dunne: When you were done with football and you’re moving on with your life, was it 2006 that you had a moment that was pretty profound? You’re dealing with some depression and suicidal thoughts like those other guys that I mentioned earlier? How did you get to this point where you’re mentally sharp, you’re entertaining as hell on a podcast like this loving life?

Hoard: They would always ask, “Are you suicidal?” And I said, “Not to seem crass or something like that. I’m not one of those people that thinks about it.” If I ever got to that point, it would be done. That’s just my nature. And so when I say that, people kind of step back and go, “What did he mean by that?” And I say, “I’ll tell you exactly what I mean: Probably not.” And any time that I felt at my lowest of lows, somebody else would do it and it’d be a wake-up call. So maybe somebody was looking out for me because I never got to that point. It wasn’t a depression thing. You had this thing for so long in your life and there’s nothing that’s going to fill that void. And the friends that you had and made are still playing football, and now you’re an outsider. So the only group that — and keep in mind — this is my own doing. I know my friends to this day didn’t think that, right? I know the Minnesota Vikings didn’t think that. I know the Cleveland Browns didn’t think that, but I felt that way: that if I wasn’t playing football, I’m not just going to go around.

And then you kind of try to figure out, OK, what can I do? Because keep in mind, my body’s going through some stuff. I had a bunch of surgeries just to try to stay reasonably healthy. And so I’m going through all this. I’m having these surgeries while all this other stuff is going on at the same time. So when people say, “Is that depression?” I would say, “No. I was just kind of in a rut.” It happens, right? It happens to everybody where you’re just blah. And so we’ve given that a name because for some reason everybody think there’s a drug that can fix it. But I don’t know if I was depressed or suicidal or any of that. People say, “Were you suicidal?” No, I probably would’ve did it if I was. I’m not going to sit around and mull over it. And I don’t know any other way how to tell them “No, I wasn’t” other than saying that. But it was a period of time where I just need to figure out what to do. Believe it or not, down here in Miami, (former Vikings RB) Robert Smith had a radio show that he was just doing on the weekends. And he was like, “Hey man, why don’t you just come do this show with me and see if you like it?”

Now me and Robert could not be more opposite. I like the laughs and the shenanigans. He likes talking about Formula 1. We’re best of friends, but our personalities couldn’t be any farther from each other. But then I started doing it and then they said, “Hey, why don’t you do it on Mondays after football and then Fridays before?” And I started doing that. I tell people: “Sports is killing me and sports is saving my life at the same time.” Because I get to talk about it, I get to watch it, I get to follow it, and it’s exciting. And yet my body’s breaking down.

Dunne: You’re dealing with stuff still right now, physically?

Hoard: God, yes. I’m going to physical therapy right now because a couple of weeks I got up and I couldn’t lift my arm over my head. I’m like, “What happened?” But I had rotator cuff surgery. So they think I have sutures in there and something might be loose or something.

Dunne: Day-to-day, you’re feeling something.

Hoard: Just staying day to day. The pain part of it, I’m used to. But when you can’t move or you’re not mobile, that’s the stuff that becomes difficult. Other than that, I do radio. I get to run my mouth. I have a set-up at my house, so if I’m not feeling good, I can do it from my house. My only regret is they don’t pay me by a word. I like following sports. I like telling stories. I do a show with a fan, so we get into it a lot because a lot of times fans direct the issue of a game to what they see and not about what happened. And so, we go back and forth a lot about that because everybody’s like “Oh, this guy’s terrible. This guy’s terrible.” I’m like, “He’ll be on the team next year.” He goes, “Why?” I said, “Because there’s only a handful of players in NFL that play offensive linemen that can play three positions on offensive line. And every team wants one of those guys. Whether they suck at it or not.”

Dunne: This is a good one to end on because you’ve got some intimate knowledge. You had the boots on the ground once upon a time. This is what everybody’s talking about. Well, maybe not everybody, because it is a little disturbing and disgusting. Did you know in the mid-90s that Bill Belichick one day would prey on women less than a third of his age?

Hoard: Hey, you know what my motto is? Whatever their agreement is, whatever their understanding is with their relationship, ain’t none of our damn business. Come on, man. We see couples together all the time and we say, “How did that happen?”

Dunne: We’re trying to get you to rip Bill Belichick.

Hoard: Listen, listen. The way I look at it is this way. If two people are happy and two people are in agreement of why they’re together and they’re happy together with that agreement, then that’s two happy people. We need more happy people on this damn earth. There’s too many old curmudgeony, mean, grumpy people. So maybe they all need to find somebody half their age or quarter their age. I am just saying. We don't know what their situation is. You walk the streets all the time. You go to a game or whatever and you’ll see a couple together and you go, “How’d that happen?” We always do it. It’s the human nature. And so guess what, whatever they got going on, it works for them.

Dunne: Does it work for the University of North Carolina though? The wild part is Mr. “Do Your Job” and “Don’t be distraction” has become a little bit of a distraction for the Tar Heels.

Hoard: You know why? Because there ain’t no football yet. You wait until football starts, OK? That man wants to coach. And I will say this about Bill Belichick. If you ask any player, you have never been more prepared to play a football game than you were when Bill Belichick was your coach. I promise you that. Before the games, you know how the coaches would go and shake everybody’s hand. Bill Belichick would tell all 46 guys dressed about a player that they would play against on that day. Every week. For every year he was the coach. That level of commitment is unheard of. And so was he tough? Absolutely. Did he have the personality of an oyster? Absolutely. But as far as respect for what that man did and how he did it, and how some of the guys — when he was the coach at Cleveland — played the best football of their career, I ain’t going to never say nothing bad about Bill Belichick ever, ever. Because he should have never got fired.

Keep in mind, we were damn near leading the division when they announced in the middle of the season that the team was leaving and then we had blackouts and boo’s and all that. And I would ask you, whatever you do in life, could you work under those conditions that we were asked to go play football in front of? You could say, “You got to be a pro. You got to be a pro.” But I’m telling you, everybody was there to boo Art Modell. They weren’t there to cheer for the Browns. They wanted to go there and express their feelings about what was happening. And so we didn’t finish the season off that well, and they fired Bill Belichick. Cleveland will forever be known as the team that fired a six-time Super Bowl champ. Think about that. So even now, even down here, everybody’s going off on Mike McDaniel. Be patient. Be patient. Sometimes, new coaches need to learn like new players. Stop making it sound like, “Oh, you just got a new job. You’re supposed to be the best version of you right away.” It doesn’t work like that for anybody.

Dunne: You said on this show in 2021 when everybody was screaming the opposite: Baker Mayfield should be the quarterback in Cleveland. A little patience there would’ve behooved the Browns.

Hoard: First of all, people need to be truthful about the circumstances. Here’s what I would say on the circumstances of why Kevin Stefanski is still the coach. The success that he’s had with the number of different quarterbacks that he’s had is unheard of. So stop it! That’s a fact. Whatever you think about Kevin Stefanski, look at his production based on what he’s had to work with. The injuries to Nick Chubb. The injuries on defense. The craziest thing that happened was Callahan leaving. People don’t realize that dude is an excellent offensive line coach. One of the best to ever do it. OK, now let’s go to Baker. He had a contract that was up. He tried to play through the shoulder. He couldn’t do it. And everybody just said he sucked. They didn’t put any text context behind it. No, he sucks. So the Browns let him go. Now, I tell you what, I’m going to be honest with you. If I was the Browns owner, you know what I would have right now, Baker Mayfield as my quarterback and $230 million in my pocket. Just saying, just saying.

Now, keep in mind at the time, I’m not mad at the owner for signing Deshaun Watson. You’re Cleveland. You’ve got to give a contract so Deshaun doesn’t get back on the plane and go somewhere else. I get that. I understand that. It didn’t work out. And guess what? Hey, people out there, you know what? You can make all the right decisions in your life. It doesn’t mean they’re all going to work out. Put your big boy pants on, be an adult! Every right decision that you’ve made in your life did not work out. It happens in sports. Now, the only thing I would say about the Deshaun thing, OK, if you need a quarterback, you’re not going to sign a quarterback that may get suspended for 10 games. You’re throwing away a year. I don’t care how good he is. That’s the only problem I had with that. It wasn’t resolved. You signed him to all that money and now you have a quarterback that hadn’t played for two years.

Dunne: He was also the most vilified athlete in the league.

Hoard: I don’t care.

Dunne: I’m just saying that mentally he was broken by the time he was out there. His confidence.

Hoard: Let’s put our big boy pants on and let’s have a conversation about the realities of society. There’s a lot of things going on in the world. You have to separate the person from the job. Meaning that we all know how good Deshaun Watson was. The other stuff kind of put him in a bad light, but we’ve had a lot of jackasses playing football.

Dunne: I’m saying that I don’t think Deshaun Watson was able to separate the storm from the quarterback. He was different.

Hoard: It seems that way. And I stood by him. I’m giving him all opportunities because guess what? I can say all the stuff he got caught up in was low rent. It was terrible. It put him in a bad light and it was well-deserved. And then on the other side, I can say he’s a hell of a quarterback. I ain’t going to eat dinner with him and we ain’t going to kick it, but he can play quarterback. We’ve had people like that in sports. Stop acting like all of a sudden, this is an exception to the rule. No, no. We got people that we work with on a daily basis that get caught up in some stuff. That’s life. And what I can do is — as a grown man, as an adult — I can separate the artist from the person. I can like your music, but hate you as a person. That’s life. Because guess what? If we live by the rules that people expect, all these athletes and teams — “Oh, that guy’s a jackass, he can’t be on my team — where would this country be if we did that? If we did that across the board to everybody and said these words: “that guy’s a jackass, I don’t want him running nothing. I’m a people person. I’m not a political guy. All my comments have to do with people. I look at people. You could be the best businessman in the world, and me personally? If you’re a jackass, I can’t do business with you. I don’t care how much money he’s going to bring me, because that means I can’t trust you. I’m always going to be looking at you like, ‘Can’t do it.’”

Dunne: Life advice for all. Leroy Hoard, this was fantastic. Always good to catch up with you. Down there in South Florida, what’s the station again?

Hoard: I am WQAM 10 to 2 on 560. I told you how I feel about the Browns. Everybody knows how I feel about the Browns. The people in Minnesota were so nice to me when I got there, and part of the reason is because they needed a running back. And when I got there, I played pretty good. So it worked out. So I was there for five years, had some playoff runs. It was really cool. Had fun, made a lot of friends. The city was unbelievable. I think I was fortunate in that I got to play in two of the cities with some of the most rabid fans and it was awesome. So I’m going to London. I haven’t quite figured out how I'm going to do it. Do I go to a Vikings tailgate, Browns tailgate?

Dunne: You need a jersey cut down in the middle.

Hoard: I haven’t figured out what I’m going to do, but I’m going to the game. I think there’s a fan experience out there. I'll put it on my Twitter. If you're wondering what my Twitter is, it’s @BigMouthLeroy. I’m going to put it there. It should be really cool. People have been asking me since I said I was going to go, “Well, who are you going to?” I had more success in Minnesota, but I’m forever known as a Cleveland Brown.

Dunne: Yeah, I was going to ask if that was real. It feels that way.

Hoard: My last two years in the league, I got 25 touchdowns. And maybe 1,200 yards.

Dunne: It’s nostalgia. The last gasp of Browns glory there. Getting into the playoffs, winning a game, then it all fell apart. Thanks, Art Modell.

Hoard: I would say this, politicians have the ability to put the proper twist on things. When I first got to Cleveland, there was diagram of a new stadium in Berea at Baldwin-Wallace in the area. A new stadium. And they were saying, “This is going to be built in the next couple of years.” It wasn't. I would say this, “There ain’t no way in hell the NFL would let that team leave if there was really a stadium planned.” … Who buttered that city’s bread and you don’t build the stadium. I don’t necessarily agree with the actions, but I can’t be mad at him. But because people went out there and kind of put everything out there and put their twist on it, I don’t think people really understood what was really going on. And that’s unfair to everybody involved. The fans. The players. The Browns. The city. It was unfair to everybody to have to deal with that without actually knowing the real truth.