Erik Kramer Q&A: 'I’m here to help people'

The quarterback details his "Ultimate Comeback," and why he's still fighting.

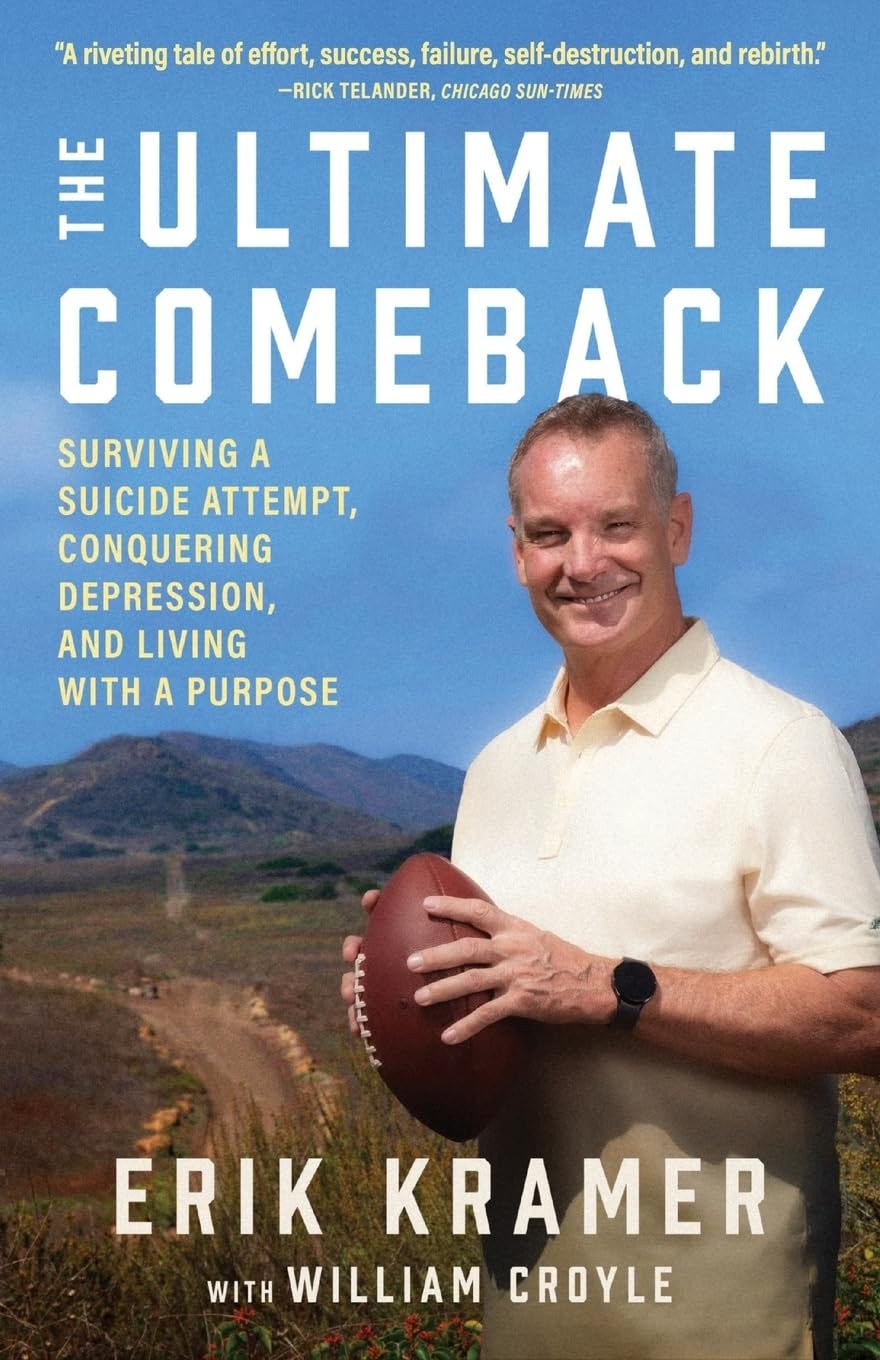

Erik Kramer does not take today for granted. He survived a suicide attempt and he survived an equally haunting conservatorship system that nearly ruined his life again. The fight for his life was the subject of a three-part series here at Go Long and, now, Kramer is detailing everything in an autobiography: “The Ultimate Comeback.”

Audio and video of our conversation is posted here.

Text is below.

Thank you for making our longform part of your day.

How in the hell are you doing? It’s great to see your face, your smile, your joy. You’re in such a phenomenal place today. How’s life?

Kramer: Life couldn’t be any better actually, so everything is going well. Obviously you mentioned the book, “The Ultimate Comeback” has been doing very well and it’s kind of just getting started in terms of talking about it and articles being done and interviews and so forth. And I’ve got a couple of nonprofits that I’ve been working on these last three or four years. And so one of ‘em happens to be a mental health program for kids and families called “Mental Health Touchdown.” We were going to start it back in August, an after-school program for fourth-, fifth-, and sixth-graders, but kind of got delayed with this book. And then a passing camp. An offseason one that’s going to be for all positions, including centers. Probably by Year 2 it’ll be not just for the 7-on-7 people, but probably offense and defensive linemen as well. A lot you can do there in a non-contact way.

Obviously you attempted suicide, survived that attempt and that might not even be the craziest element of your story. Everything that happened after that — you’re coerced into a sham marriage — you revert back to mentally being a little kid. So you don’t really know what’s going on in your life. But let’s start at the start because I really didn’t know a lot about your upbringing and what led you to the NFL because that story alone is inspiring. You were a high school defensive back, you didn’t play quarterback. You get to Pierce Junior College and you’re a backup and you had that epiphany like, “I have to quit being selfish, quit having this big ego.” But how did you even get to the NFL?

Kramer: A circuitous route, obviously. Didn’t get drafted. I had a good college career. I was ACC Player of the Year at N.C. State my senior year. Tried out for the New Orleans Saints and I knew the day I got there I wasn’t going to make it. I still made good friends while I was there and was back in school in time for the college football season to begin. And so I was helping out with the football team and thought I was going be a high school coach. Then the strike happened in 1987. And so I got a few calls from some teams and I ended up playing for Atlanta for three games. And they ended up keeping me that year. The following year in training camp, I was the last cut because the Rams had cut both of their backup quarterbacks. And so Atlanta picked them both up and I ended up waiting around for a few weeks. Nobody else called. And so I went up and played in Canada in the CFL. There were six games left in their schedule. I came in after halftime of the first game and then played the rest of the way.

Didn’t do anything special. And then ended up calling around to all the teams and the Lions were the only team to give me a callback. And through writing this book, I talked to June Jones who was the receivers coach there. Prior to the Lions, he was the quarterback coach and offensive coordinator for the then-Houston Oilers and they drafted a receiver, that we had (at N.C. State), in the first round named Haywood Jeffries. Even going back to the strike, he said, “Yeah, looked at some of that stuff and thought you could play.” And so it was interesting because they flew me out there and this is in the middle of January. So I’m sitting in the lobby and it’s at the Silverdome. There was nobody in town to work out and the turf in the Silverdome was rolled up. They had something else going on and I didn’t know that at the time. So the woman comes out and says, “Hey, you can sit in this office here.” This was Mouse Davis, the offensive coordinator then. I’m sitting there for a few minutes and he comes walking in and goes, “Who are you?” I got called in here to come work out. And so he goes, “Hold on a second.” He walks back out and he goes, “Alright, how about we get in my car and you, June and I will drive down to Ann Arbor.” The University of Michigan has an indoor field, and I remember Alan Trammell was hitting in the batting cage in one of the end zones. Literally my workout was me dropping back and June — wherever he was — I’d be throwing him the ball. That was my workout.

When you are trying to get back in the NFL, after you had the little cameo during the strike, you busted out a media guide and you’re literally going team-to-team just calling these teams saying, “Hey, Erik Kramer here. Would love to work out!” And the Lions were the one team that entertained it? And then you get out there: “Who are you? OK, I guess you made the trip from California. We’ll do something.”

Kramer: Not just that. They had a minicamp in March down in Tampa. We were on the field at what was then the old stadium for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers. So, the draft wasn’t until the end of April. So at the time there was Bob Gagliano, Rodney Peete and then me. And so the draft happens — and back then ESPN wasn’t covering the draft — and so I had somehow heard that Andre Ware got picked with the seventh pick, whatever it was, and I’m like, “Huh, here’s the guy who just won the Heisman Trophy and ran this offense in college. I’m probably going to get a phone call here in about five minutes saying ‘Hey, thanks for, but no thanks.’” But they didn’t.

And he held out, which kind of gave you an opening.

Kramer: He did. I kind of got rejuvenated when I showed up. Andre wasn’t the nicest guy in the world. He kind of strutted around like he was it. Which he really wasn’t. So, he had a hard time playing catch, combined with the bad attitude. And then he held out, like you said. But he didn’t do himself any favors because it wasn’t like he ingratiated himself to anybody. He just had this air like he thought he was God’s gift to football, which he turned out not to be. And so when you’re not humble like that, there’s probably not much you’re going to learn along the way other than hard lessons. And so that’s what happened. And so he played himself out and I kind of played myself in.

I think too, you had that epiphany — that bad-attitude epiphany — earlier. You’re at Pierce and you’re on the other side from the team on the sideline. Distant. Sulking. Thinking you should be out there as the starter. Take us through that. That struck me as a turning point in terms of football for you where if you don’t have that epiphany, nobody really hears about “Erik Kramer” beyond Pierce Junior College.

Kramer: That’s where the whole thing flipped. And I’ll say this: We’re all products of our environment growing up and my dad was a double-sided corn. On one hand, he believed in me to the degree where everybody else must have thought he was a knucklehead. Because there really wasn’t much evidence to show that I was going anywhere. On the other hand, he also lived through me. The way he went about life, unfortunately for him — and this goes back to his background growing up — is he tried to make people consciously or unconsciously feel sorry for him. And so I kind of, in a way, followed that at Pierce College where I thought I’d won this quarterback battle. Not even close. And the head coach didn’t see it that way. And so it’s not like we ever had a conversation about it. We’d be playing games and I’d be sulking down on one sideline and every other Pierce Brahma was down at the other end. What happened is, when I would get in the game, my mind wouldn’t be in the right spot. So, it didn’t take me that long, maybe four or five games. And then I figured out as much as I’m doing for myself, I might as well help out Dave who was playing. It set me up for all things good in the future, meaning I shifted away from what was good for me as opposed to what was good for the team. And it's amazing how that works.

Your relationship with your Dad. Complicated doesn’t really do it justice, and your Mom as well. How would you describe your relationship with your Dad? I mean, he’s in the room with the Pierce coaches convincing them — by the way, growing up, he called it a “loser school.” He envisioned you at USC or UCLA. You don't even play quarterback in high school. They’ve got you at DB. But he does talk them into giving his son a chance. He’s the only parent in the stands at practice and you’re like, “Dad, come on, quit doing that.” Then he’s hiding in the trees, camouflaging in.

Kramer: I would have to set his boundaries. But he always thought those boundaries were dotted. He didn’t have a way of going, “Oh really? When I do that to you, how does that feel?” There was never that. It was like, “Oh, really?” It didn’t even occur to him that would be an issue.

He lived in chaos is the way you described it. Chaos and disorder.

Kramer: Right. And when you get around to it, he didn’t have an upbringing anybody would want. No one. His Mom apparently left him and his Dad when he was 2 years old. He told me he never saw her again, but that’s not what I heard. I heard he did see her again but didn’t really like what he saw. And then his Dad basically shipped him off. His family on his Dad’s side is from Oklahoma, and so he grew up with his aunt’s family and never really had one of his own and then didn’t reunite with his Dad until he started high school. And by then his Dad was married again for the third or fourth time. It’s not an upbringing I would’ve wanted and I don’t think there’s a long list of people who would want that. And so he didn’t really know what being a Dad was and probably didn’t know what being a husband was. He has passed away now, as is my Mom, and in those ways you have to have a soft spot in your heart for somebody like that.

Which says a lot about you because he was unbelievably overbearing. But you get to the NFL — to fast forward again — and it’s crazy. You’re not that big. You’re not that athletic. You don’t really have that strong of an arm, but you’re mentally tough. You’re physically tough. And you’re smart. How would you explain that near-instant success. You get your chance, you reel off some wins, you lead the Detroit Lions to their first playoff win in three decades and it’s been three decades since. It’s unbelievable. How does that happen? How is Erik Kramer the quarterback who pulls that off?

Kramer: It’s like the overnight band success that nobody’s ever heard of that’s been playing in clubs for 30 years and then, all of a sudden, they come out with their 880th song that makes it to the top. Well, there was a lot of songs before that that got them there, and I think that’s basically what happened. Everything in life — and what you do with your life — is always an evolution. And so you’re always getting a little bit better hopefully. Sometimes a little worse, or in fact, learning from your mistakes on the path as well. And so eventually you get an opportunity and it's the right one at the right time, and I always equate my career to, I’m standing in line and right then something’s happened to the guy that’s playing and the coach turns around and say, “Who’s ready next? And everyone else happened to be tying their shoes at that time. And then there I was. And that's kind of how it worked out — honestly. Good things happened from the very beginning. But it’s only because I was ready. It wasn’t because I lucked into it.

You created your own luck through hard work and selflessness and a lot of qualities that your Dad didn’t have. Because you don’t just get that call from Dave Wannstedt with an offer for $8 mill over three years.

Kramer: A lot for a guy who didn’t even, like you mentioned before, I was on the path to play quarterback. Back when I was in high school, they didn’t have freshmen. High school was 10th through 12th, and so when I was a freshman, I played youth football. That was my last year. And then as a 10th grader, I started on JV. But then three or four games into it, broke a collarbone and was done for the year. Backed up as a junior. Changed schools in-between my 11th and 12th grade year in that second semester. Went to a different school. Again, this was all sought after by my Dad. I had nothing to do with this.

My Dad and I met the head coach at that time who I later found out passed away. After reading his obituary, I found out that he was a receiver at San Jose State on the same team with Bill Walsh and whatever. We met at a Bob’s Big Boy. Next thing I know I’m going to Burroughs and there was a quarterback battle between me and another guy, which he was a good athletic quarterback in high school. He won it. I think we switched off for four games. And then we didn’t lose again. We went to the CF championship, lost there. That was my start to this whole thing. But I realized after a while that what you have to do — in addition to everything physically — meaning running, stretching, lifting, weights, watching film, what eventually tied it all together for me was a guy named Kevin Wildenhaus. My first year with the Lions, I was on injured reserve and back then when you’re injured reserve, you’re there all year. And so in practice, I had a hard time slowing things down mentally. I literally went to the team internist and “Hey, here’s what’s going on.” He says, “Here. Go see this guy.” That’s a friendship that I’ve had now since then with Kevin. It was this ability to have mindfulness. Visualization. It's guided imagery, basically. And a way to breathe that allows you to slow everything down. And so that’s how you want to go through life and also — if you’re playing a sport or whatever it is you're doing — if you can encounter the world like that, that’s a good way to go through things.

I like the analogy that he used with you in terms of being on an inner tube, kind of going down a river and you’ve got to avoid jagged rocks. You’re moving in one direction, but you still have to kind of avoid obstacles. And it’s a lot like playing quarterback in the pocket. That seemed to be a turning point for you in the pros. You’ve got blitzers in your face, you’ve got to dissect coverages. But you can’t do one… at… a… time when a play happens in 3 ½, 4 seconds.

Kramer: So I envisioned this water sort of flowing down gently, not this rushing river. Because water, when it encounters something like a rock or a boulder, it doesn’t stop and shift gears. It just meanders and gravity takes it wherever it wants to go. And so that’s how you want to play. That’s how I envisioned playing. Everything really does slow down. And I remember Kevin using some imagery: “If you were a camera lens, Erik, and you would go from, let’s say the play gets called and as you’re walking to the line, you begin to notice not only the coverage in sort of this wide-angle view, but you would also notice, is the cornerback inside or outside and are there any tips here that look like a blitz or not?” You visualize what the play would be before you even call it in the huddle. And these are all things that kind of need a slowed-down pace, but sort of in-order pace to it as well.

I am so fascinated by mental health in the NFL. Kalif Raymond for the Lions, he was in a really dark place a few years back and he got into mindfulness. That was such an important moment for him. He’s muffing punts. He’s having these sleepless nights and he’d do these float sessions and a lot of meditation. He kind of compared it to — I’m looking at it right now on my laptop. I’ve got Firefox up and there’s like 15 tabs. I don’t need those 15 tabs open. He said it’s like closing tabs in your life. If you can somehow just eliminate clutter and focus on whatever’s right in front of you, that goes such a long way.

Kramer: It’s really amazing. The way I always looked at it, I wasn’t naturally flexible. So, I began stretching. I wasn’t naturally fast. So, I began running. I didn’t have a lot of cardiovascular ability, so I started running distance and interval training. And then I wasn’t very strong, so I got in the weight room. All those things didn’t add up to what I was looking for. What was the glove that made all the fingers fit just right was Kevin Wildenhaus. Putting it all together mentally. It’s not just mentally. It’s emotionally, and Kevin began to — over time — learn about what we’ve been talking about here: About my upbringing and parents and kind of craft that with a few exercises as well. And so it’s kind of like Kalif Raymond was telling you. You’re being able to accept, but then close that tab and look at this other tab with a little different set of understanding and perspective than you may have had before. That way, you can close that one, too. And if you want to open that back up when you’re ready, fine. But it doesn't have to stay open. And so it allows you to really just focus on what’s in front of you and not have to give any energy to, “Oh, there’s these other things open that eventually I’m going to have to look over here while I’m doing this.” And that’s really what frees up the person to not just mentally — but emotionally — focus in on the task at hand.

Because you got that contract from the Bears and things started terribly in 1994. You had some rough games. You’re eventually benched. You’re thinking, “This is it.” And I think that was really your first bout with depression.

This is from “Depression and a Mother’s Love” on Page 100. You wrote: “Nothing felt adequate anymore. My marriage never did, but at this point, I was also discounting my abilities as a father, especially after Griffen’s tenuous start to life. It was an unjust assessment, but self-doubt rules every thought when you’re mired in depression. I questioned my career and my capability to continue playing. My shoulder is healed, but will there be a lasting impact? Will I be able to effectively throw a ball again. My last start against the Lions suggested that I might not. Even if I can, will the Bears still want me? Will any team? What will I do with the rest of my life if I’m a washed-up player at the age of 30? Instead of seeing the world and my life with a floodlight, I could only see them with a narrow laser beam that was fixed on the pain, sadness, and suffering. I lost my ability to see the big picture, alternatives to my problems, and any hope for a better tomorrow.”

What was it like when depression first really worked its way into your life? Because it seemed like ‘94 was maybe that first domino.

Kramer: If you look up in the dictionary, the definition for “depression,” that’d be pretty good summation right there. You now live in — or I at that time — now live in a hole where there was no light. You lose all perspective. Depression has a way of seeping in and, while you’re not looking, it basically zaps you of all perspective. It zaps you of the aerial view of your life. All this self-doubt really creeps in. The ability literally to go down and even want to eat breakfast is now gone. Get out of bed? Gone. Although, you’ve got to be there in an hour. And so you still have to go. And being able to walk around and invest yourself in what you’ve always done in preparing and doing, now your motivation for doing that is gone. And so being able to keep moving forward during that time was very, very difficult.

I remember my Mom and I, our relationship was altogether different than my Dad’s and I. So we weren’t close, either, for other reasons. And I remember talking to her during that time and I don’t know what I said, but she eventually said, “Look, I’m coming out there.” I said, “Oh, OK, great.” I don’t remember what she did when she got out there, but my Mom was pretty good at walking into an environment — say a house — and just kind of sitting back and assessing: What can I do? And it wasn’t like she came in and steamrolled everything. She just kind of, “Oh, maybe I can do this and do that.” And remember at that time, Griffen was maybe, a year and a half.

She found her way to helping with him and whatever else. And I’d say she was there probably a week. But for her to put her own life on hold for a week was a big deal. And so that touched me. And I won’t say that any one thing by itself helped turn it around. But I know eventually talking with a therapist and some antidepressants definitely helped. And just kind of a combination of people… it didn’t take many. One, two people to just continually be there. And if you feel like talking, they’re the person to talk to. And if you don’t feel like talking, that’s fine, too. Eventually knowing that — and you don’t know at the time — but depression is temporary. At least it was for me. And if you can get one or two people around you — whether it be a therapist, because they’re the ones professionally trained at listening and insightfully listening to the point where they can have a suggestion or two that might give you a little bit different perspective than what you’ve got. In addition to that, maybe one or two or at the most three people that feel to you a safe place to land, that just by virtue of them listening, that’s enough. It’s not anything earth-shattering, but it can lift you out of the cage you feel yourself in. It will over time. And the hard thing with depression is there’s no aspirin to take that makes you go, “Oh, now I feel better.” It doesn’t happen that way. And so if you can just know that if your patient — and the people around you will continually show up for you — in time, this will get better.

I would’ve thought that 1995 season would serve as that cure-all injection. The Chicago Bears, we’re not talking about a team that’s been around a decade or two. We’re talking about the Chicago Bears. You set single-season records for passing yards, 3,838. Passing touchdowns, 29. You only threw 10 picks. It all comes together in ‘95, but it’s not like that just made the depression go away. I think that next year, into ‘96, there’s no explanation for it. It seeps back into your mind. How did that depression linger and linger and linger to the point where, alright, now these suicidal thoughts are a little more real than they were in 1994?

Kramer: If I had to guess here, I’d say probably seven, eight times. I had never had a bout (of depression) that at some point or another didn’t have an accompanying thought of suicide. The two for me anyway went hand in hand. It’s not like every day. But it was like “This is really hard to get through a day and have a thought that feels good in any way during a part of a day, have that day something happened that’s good. And how long do I want to keep doing this?” And it’s almost like “I’d be doing everybody a favor if I wasn’t here.” Because if you’re your own counsel and you’re only your own counsel, that’s the worst person you could actually rely on. And so how this stuff happens and how this comes back into being, I don’t know. That’s why I would say that the thing to do is a.) Be proactive and not wait. And start to observe people. You do anyway. So observe those that seem like they could be somebody that would be that active listener. Active, non-judgmental, empathetic. Someone that can empathize with what you’re doing and saying, put themselves in your shoes and listen from that perspective. And maybe have a way to help guide you in a way that says, “Hey, I’m willing to be here anytime this happens, day or night, doesn’t matter. I’m the person you call.” And so you want two or three of those ahead of time just as part of your daily life. And then that way, if at some point life kind of starts to go severely downward, before it gets too far someone's going to notice that you don’t quite seem the same. They might not wait for you to come to them. They’ll ask you first. Building your own little home team, even as a kid, to me is the way to go about this.

Again, everybody’s going to buy “The Ultimate Comeback” and get every detail, but what really led you to that hotel room, for those who didn’t read the series, to the point where you’re checking into a hotel with the full intent to shoot yourself and end your life?

Kramer: What led to that were several things. I was done playing. I was working at Fox. I had coached both of my sons through their youth football years during that same time. I had a little passing camp going on with former teammate Curtis Conway and that same former junior college coach, Jim Fenwick. And then my Mom — this was back on Mother’s Day — so she was a golfer. She was actually better than me. She went out to golf one day and it was Mother’s Day and as I’m walking into the car, she says, “Hey, I’m going to get some tests back tomorrow.” And I said, “Really? For what?” And she says, “Oh, I just haven’t been feeling all that great.” I said, “Oh, OK, well let me know the results.” And she calls the next day and she says, “OK, sit down. I’ve got Stage 4 Uterine cancer.” So… “What?” She was married at that time and her husband Doug found an oncologist and they did some wicked surgery where they had to remove parts of more than one organ. And that nearly killed her, but it didn’t. And so she recovered. The cancer returned and, around that time, she would have doctor visits that I would take her to, she would have her chemo, which I would stay overnight with her in the hospital for. And she was doing OK there for a while.

And then in October, my wife and I, Marshawn, were separated at that time. Griffen chose to live with Marshawn. And this was after he had come out of this outpatient program at Visions where he would live at home and then pretty much be gone all day at meetings and eventually there was sort of this individualized school that he would go to that started giving him some belief in himself again. But I could see he kind of had his eyes on the finish line. Which he was done about February or March of that year — in 2011. And then Oct. 30, I get a phone call from the sheriff’s department. But it was in the morning and he wouldn’t tell me what's going on. So I walk up the steps at the local sheriff’s department and before I even could get in the door, the officer walked outside and said, “Your son didn’t make it through the night.” I said, “What?” He said, “Yeah, he passed away.” And so we literally drove to that house that it happened to occur in. And it’s just… tough.

And then around about eight months later, in July, my Mom eventually passed away. She had home hospice for about two or three days. She was at West Hills Hospital and the doctor grabbed a few of us that were in there and said, “OK, it's time. She’s not going to make it so she can either stay here or she can go home and have home hospice.” So we all go back into her room and the doctor basically tells her. You know those little triangle bars that hang down over the head of the bed? As the doctor’s telling her this, she starts these pull-ups. She goes, “I feel good!” So unfortunately, she didn’t make it.

And then around that time that she passed away, my Dad had some untreated acid reflex that eventually turned into Esophageal cancer, which was about a three-year steady decline. And there was for him, no getting out of that. The feeling I had at that time was that all the significant people in my life were going that way and there was really no one left coming this way. And that’s not a ship that turns around easily. That led me to of all places the Good Nite Inn, and Dillon wasn’t living with me either. He was living with Marshawn. Unfortunately, this gave me too much time on my own hands to contemplate and then fully go execute an exit. So I didn't want Dillon walking into my house with that scene. So, I purchased a gun and of all things go to a shooting range. Like shooting down the range. And what I was going to do had nothing to do with that. … It was the day before Dillon, my youngest son’s first day of school. He was going to be a junior in high school. Again, you lose all perspective. You don’t think, “What’s this going to do to everybody else?” Because for the person who does commit suicide, it’s over. Everybody else, it’s just beginning. And so thankfully through some unbelievable doctors and the support of those around me, here I am. I couldn’t be more grateful. I don’t feel any regret because you only make the decisions you have based on the information and how you’re feeling and the thoughts you have at the time. But I’m so grateful that what I did I wasn’t successful at. And so now I get a chance to be here for all of them and do some good with what would be the ultimate second chance.

I’m sure people are listening and thinking, how does one go to shoot themselves in a hotel room and survive? That day, that night is a little difficult to recall but how did you survive?

Kramer: I don’t know.

Did the doctors tell you? The reconstructive surgery was pretty intense, right?

Kramer: There was a time when, if I turned to the side here, there was part of my forehead missing. So literally my head went back that way. And this is not mine. (Pointing to side of forehead) This is some, I don’t know, high-tech plastic. A friend of mine, Anna (Dergan), we went to high school together and I’m her oldest daughter’s godfather. Anna, who’s been there every step of the way, she takes me to a revisit with the doctor who had done the surgery that night. And so what had happened was they opened my head up and my brain began to swell. So they had to close me back up and couldn’t do what they needed to do that night. And it took them, two or three days later. So I go back for this visit and we're sitting in a normal office patient room and he’s asking me some questions and he’s standing off to the side and I’m kind of talking this way and I look up and it’s like his jaw is on the ground. I said, “Did I say something wrong?” And he goes, “Oh, no, no, sorry. You have to understand that people that were in a situation you were in aren’t usually back here talking to me about it later.” That showed me that I’m a lucky guy.

And to go back to that scenario where I had gone to Detroit as part of a way to publicize this book, and one of the interviews I did was a woman named Jen Hammond who had been waiting for this book to come out. And so she comes and there’s a hotel room I’ve got and we’re sitting apart across from each other. And she says, “Normally you would start an interview chronologically, but I’m just going to start at the end. You weren’t supposed to be here, were you?” I go, “I guess you’re right. But I am.” She goes, “Why do you think that is?” I go, “Well, because I think I’m here to help people.”

So it makes me feel good because I originally wanted to do this for Griffen and Dillon. And so the trickle effect is that I’ve been getting a lot of feedback from people who’ve read it who are friends of mine. One night I’m watching some Netflix show and a text comes in. It’s from a very good friend I went to college with and he says, “I’ve never read one book cover to cover except this one.” And he goes, “I always looked up to you and respected you based on who I thought I knew you were having no idea this all happened.” Anyway, it’s been good because I think as you mentioned, this little story here has positively affected some people in a very good way.

And it’s only possible because you are so raw and open. You don’t hold anything back. From your childhood to today, you bare your soul and it’s really a journey of the mind. Football is a part of it, here and there, but you take everyone through mentally where you’re at your entire life. I think it transcends sports. Even after you survived that, the surgery is amazing. And looking at you now is just how I looked at you a few years ago. You’d never know anything happened. Even speaking to you shortly after the suicide attempt, you’d never really know. But that wasn’t the case mentally, was it? You weren’t Erik Kramer.

Kramer: No. If you’ve got a broken arm, you’ve got a cast on. You’ve got something going on with your brain, no one can see it. And so you would have to kind of have known me to know that after a few minutes, he doesn't quite sound right. If you were around me and you had some bad intentions — meaning if you wanted to take advantage of me — I was very easy to take advantage of. And was. But those people around me, like Anna and other family members and friends, knew that this is the time that someone like me needs to be looked after. And in many ways, the justice system prevented that from happening and they were part of the ones that took advantage. And so it is not limited to the people who do it illegally. It includes many people who steal illegally, but they themselves don't look at it that way.

If you could sum up that stage of your life, how difficult was it? I feel like everything that you had to deal with after the Good Nite Inn was just as bad because your life is slipping away from you and there’s not anything you can really do about it.

Kramer: No, and I guess the way I equate it now is during those years — let’s say from whenever it was, I woke up to 2019’ish. So there’s a good stretch of four years in there that I don’t really remember a whole bunch. And what I do remember, I might not remember accurately, and I equate it to let’s say a seven- or eight-year-old. If you were to take me by the hand and we’re going to walk out the front door and as soon as we get to the sidewalk — while we’re in the house you say “When we get there, we’re going to turn left — by the time we got there, I would’ve already forgotten that. You say we’re going to go right. Oh, OK, we’ll go right. And so from that seven-, eight-year-old, if you said, “If you had taken all the toys I had in the world at that age, would I have even cared? No. Now when I’m 12 or 13 and I look back and I find out what you did, now am I going to care? Yeah. Because now I’ve got my faculties about me again. And so that’s kind of how it worked.

There was only so much that people around me were able to protect me from because the legal system had their hand in the cookie jar also. This book is just the first of many things coming. But ultimately what I want to do is enact or change laws that are already on the books that don’t have enough teeth to them or ones that don’t exist need to. And so we started making some headway with that here in California several years ago. But the guy who is actually from this area, Van Nuys, he was the California State Senate majority leader, Robert Hertzberg. So he left that position, but he also put us in contact with other people that I think are on that same train. And so you can’t let these people that hide behind their legal profession or professional fiduciary bureau, you can't let them continue to, in their minds, “do their job” while stealing legally from people. You can’t do that. So the best way to do it is to, with the use of media and other avenues, is to shine the light on the cockroaches. Because there’s plenty of ‘em out there.

I had no idea about conservatorship. It’s unbelievable how bureaucracy works to steal, to ruin your life.

Kramer: All these people, whether they be lawyers, professional fiduciaries, people within companies, trust departments, officials, they all use your incapacitation to protect themselves. Think about that. I watched this docuseries, The Guardians, and it was about the conservatorship system, what they call “guardianship” in the Vegas area in Clark County. This is the fastest growing industry in America because the only way to be conserved is to have some medical brain injury or incapacitation. Let’s say you chop an arm off, that’s not going to get you into conservatorship. What is, is your mental deficiencies. Which think about that. You’ve got somebody who’s got some money in the bank with some mental deficiencies and a system in place — under the guise of, “we’re going to protect you” — but really we’re going to drain everything you have while protecting you. It is diabolical and it’s legal.

Yeah, I think you estimated Cortney, the “thief” who coerced you into this marriage, probably stole about $300,000, but then it was a legal system that stole $400,000.

Kramer: That’s right. They don’t see it that way, but I do. So yeah, it’s really just a matter of in addition to this book, shining a light. There’s been some cases, don’t get me wrong, across America. There have been several over the years. Like I said, this is a big issue. In fact, there was a movie about this: “I Care A Lot.” So it’s slowly but surely coming into the consciousness of America, but not yet enough.

Anna really was the hero in this story to kind of help you connect dots and realize what happened over those four years. The painstaking detail, it’s in our series, and of course there’s a heck of a lot more in the book, which I cannot recommend enough. It seems like everything has only gotten better and better (since we last spoke), and you’re in a great place today.

Would you say that’s the case? In terms of waking up in the morning and just being excited to attack the day?

Kramer: Yeah, I do. I feel great. At least in my case, all that was needed was time. It was August in 2015 where I did shoot myself, and now we’re in 2023, a good eight years later, and I feel back to normal. And it took probably — it wasn’t long before you and I spoke — I’d say maybe a year before things started to really get back connected. For me mentally, that’s a long time. That's four or five years. But scientifically, you talk to neuropsychologists, there was one connected with me, Dr. Tomaszewski, he says, “Yeah, for the initial recovery period, we’re talking two to three years.” That’s the initial part. “But for you to get back to normal, if there is one, now we’re talking four or five years.” Which is right about that time.

You can purchase “The Ultimate Comeback” on Amazon, and everywhere books are sold.

Our series at Go Long is below: