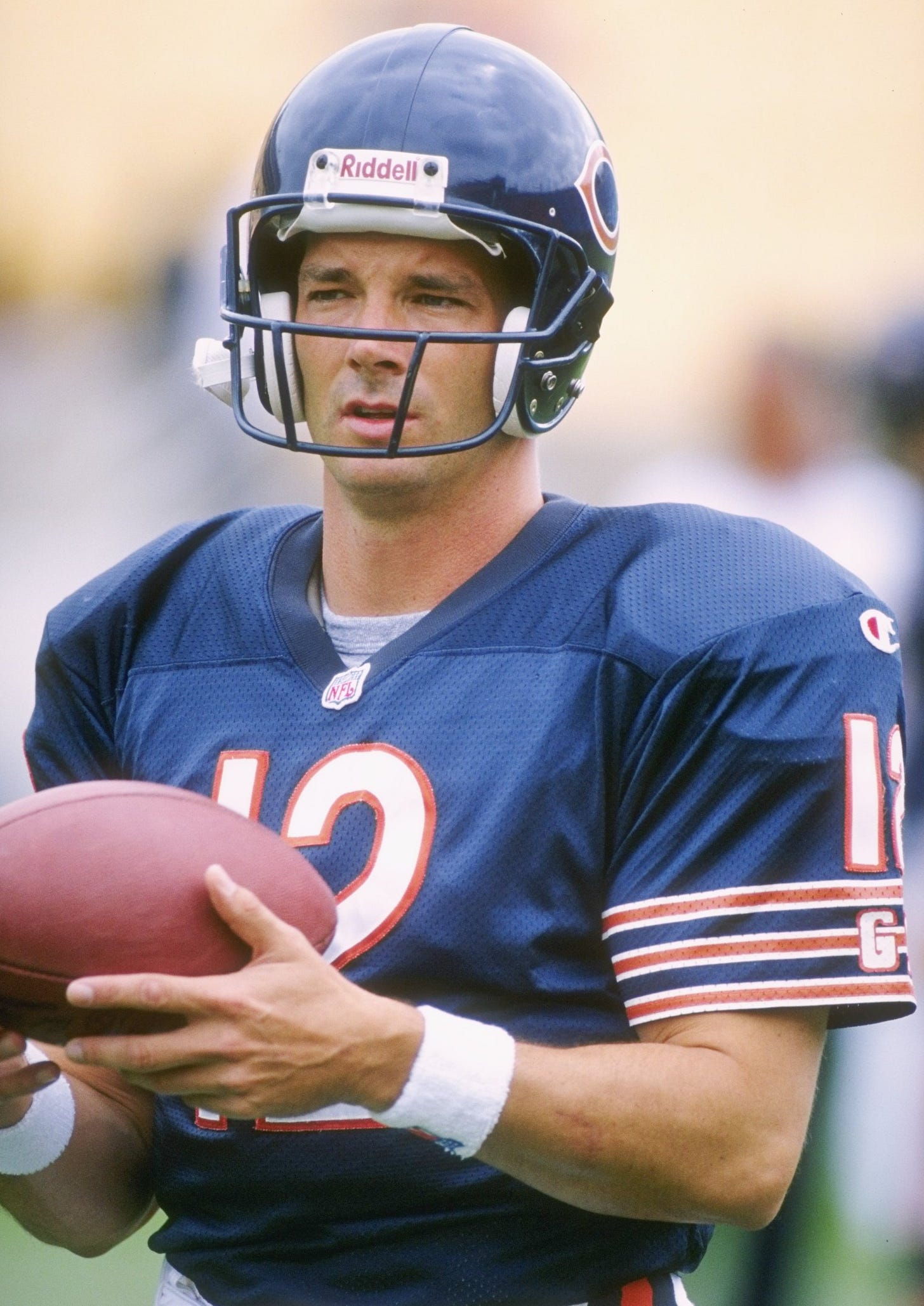

The Fight for Erik Kramer’s Life, Part II: Victimized

It took five years for his brain to wake up after attempted suicide. What happened in that time should have ruined the former NFL QB, from alleged theft, to a coerced marriage to... so much more.

First, he was depressed. After a series of tragic events, Erik Kramer decided to take his own life. He pulled that trigger… miraculously survived… and things only got wilder. When we first launched this Go Long newsletter, months ago, Kramer was one of the first players to get right back to us. He badly wanted to share what’s happened since his 10-year career wrapped up and… wow.

What Kramer has been through is almost impossible to fathom.

Miss Part I? Catch up right here.

If you were to look at Erik Kramer post-surgery, you’d have no clue anything was wrong.

No clue this was a man who tried to commit suicide.

He could walk and talk. He could even drive a car and swing a golf club.

He could coach football, becoming an assistant at a local high school. He gave frequent speeches about depression and suicide and made the media rounds. ESPN. Sports Illustrated. Bleacher Report. You name it. Even watching those gripping clips today, it’s difficult to tell anything was wrong. In one, Kramer calmly states he doesn’t have “any real mental deficiencies.” In another, a girlfriend gives him a kiss in the kitchen.

The only physical or mental scar left from that near-fatal night at the Good Night Inn — it appeared — was a minuscule abrasion underneath his chin.

A miracle, indeed.

Unfortunately, nobody knew the half of it. The resulting brain trauma from that bullet, in truth, rendered Kramer a completely different person. When a chunk of his forehead was literally shot off his head, his frontal lobe was left severely damaged. So while he could process the simple things, the part of the brain that made decisions was ravaged.

Kramer could not comprehend risk.

Kramer suddenly had the mental capacity of a six-year-old.

“I couldn’t put two and two together,” Kramer says. “If you put two and two together for me and said it was four, I would say, ‘Oh. OK.’ And then the next person would say, ‘What’s two and two?’ And I’d say, ‘I don’t know.’”

When it came to connecting dots, his brain only… buffered. A neuropsychologist named Dr. Robert Tomaszewski, who specializes in traumatic brain injuries, later explained to Kramer he was in the ultimate “vulnerable” state. Anybody could say anything to him and he’d register it as, say, Today is sunny. He’d agree unconditionally with the last thing someone told him. Because, as Dr. Tomaszewski put it, people simply do not survive what Kramer did. And those who do? It takes three to four years for the brain to heal. Considering Kramer endured three seizures, his recovery would take five years.

Imagine cutting yourself on the arm, he told them. It bleeds. It forms a scab. The scab peels off. And that whole process takes, what, two weeks? Now imagine the scab on the brain. That process takes years.

Which is why we’re sitting here on Zoom chatting about this all. It’s now been five-plus years since Kramer’s suicide attempt.

And what happened in those five years it took his brain to heal should have ruined him.

Now that he’s finally himself, he is on a mission to share his story with everyone — he previously chatted with Dan Wetzel of Yahoo! Sports. Kramer does not want anyone to ever experience what he did. For humanity’s sake, this is a story that must be told over and over and over again. In his vulnerable state, Kramer says he lost $700,000. First, there was Cortney Baird. The “thief,” he calls her. The girlfriend who coerced him into a sham marriage took $300,000 in all, he says, while a twisted legal system took another $400,000.

Kramer was living a damn nightmare and had no clue.

No, Baird did not appear out of thin air. Three weeks after Griffen passed away, in 2011, she was one of many friends to show Kramer sympathy. He remembers her bringing cupcakes over. Spending time. Baird had a seven-year-old herself and Dillon was 13 so, together, all four would pop a DVD in for a movie night. Kramer does recall watching the Pixar movie, “Up.” From there, a friendship turned into an unhealthy on-again, off-again relationship for three years. Finally, Kramer called it off for good in January 2015.

Or so he thought.

Of course, Kramer has no recollection of all the details he shares throughout our three-plus hours of conversation. He’s been able to meticulously piece the entire ordeal together with the help of family and friends, especially his close high school friend Anna Dergan.

As he recovered at the Centre for Neuro Skills, post-gunshot, the part of Kramer’s health insurance allowing him to stay overnight was running out so he decided to redirect to another brain clinic in Las Vegas area where his sister, Kelley, lived. And through a two-week gap between CNS and Vegas, Kramer stayed overnight back at his California home with the help of Dergan, who drove him to and from visits while taking an accounting class at night.

Two days before Dergan was set to drive Kramer to Vegas, she returned from one Wednesday class to see Baird sitting at the kitchen table around 9:30 p.m. As she recalls, Baird stayed until 1:30 a.m. She did all of the talking, too. Kramer barely muttered a word as Baird went on and on about how her daughter looked up to him as a Dad, how she’d take care of him, etc. The morning Kramer left for Vegas, she was back at 8:15 a.m. to say goodbye and not to be gone for too long.

Right then, in retrospect, is when Kramer believes she knew he was an easy target.

Right then, is when he believes she knew he had zero memory of their final breakup.

“I would guarantee you,” Kramer says, “that she recognized then that mentally I was not all there.”

He got to Vegas and the workers at this facility became irritated that Baird called all day long. They’d call Kramer’s sister to say Baird won’t leave him alone and it was affecting his brain recovery. And when it was time to go, Baird flew out to Vegas to drive Kramer back to California in his car.

“In that four-hour ride home, she probably figured out, ‘OK, it’s on,’” Kramer says. “And four days later I can recognize the first charge.”

Baird quit her job soon after they returned to the L.A area, moved into his home within two weeks and never left.

That point on, Kramer’s accounts were bled dry.

Know this about Kramer when it comes to money: He was regimented. He followed a strict routine in the past. With $4 million saved up in a Raymond James trust fund, he’d write himself a check worth about $10,000 per month and move it over to his West Fargo Bank checking account to cover his expenses. He was known as frugal. He rarely ever bought anything for himself. Now? He was hemorrhaging money. Sifting through old records, Baird’s spending started innocently enough with a $50 charge at a pharmacy on April 20, 2016 in Thousand Oaks, Calif.

There were some cashbacks at grocery stores. Starbucks runs. The fee for her daughter’s soccer team. Storage. She’d load up on gift cards at Vons grocery store and rip through Amazon Prime. There were enough shoe boxes in one bedroom, Kramer says, “to outfit a basketball team.” It was as if Baird started slow and gradually picked up steam, Dergan notes, to see what she could really get away with.

Next up, were daily ATM withdrawals.

Once she ran the checking account dry, Dergan explains, she moved to Griffen’s Memorial Fund account.

Once she ran this $9,984 dry, she took credit card cash advances.

From there, she forged a check.

Baird tracked and tried to mimic what Kramer did in the past with those $10,000 monthly checks pulled from the trust fund, both Dergan and the ex-QB say, by forging a check for $10,000. What Baird did not know, however, was that Raymond James took control of this account after the suicide attempt and covered his expenses themselves. Thus, when Baird likely thought there was $10,005 in the account when they took a trip to a Bears game on Oct. 1-2, the account was actually siphoned down to $5. She took out $400 the morning they left with their kids, per Kramer, and then another $300 in Chicago. Upon returning, she took another $1,200.

Finally, the original forged check bounced.

Kramer’s checking account was $6,900 in the red.

“Think for a second, if you have all your mental faculties,” Kramer says. “Just think if you saw someone who you were around all the time that didn’t and then you crafted out a plan using your mental capacities against that person. It was an unfair fight. There was no way to win. So that’s what happened.

“And then part of what Dr. Tomaszewski said is that one of the things that goes along with this type of brain injury is your ability to decipher. So, let’s say, we’re walking down the sidewalk and you say, ‘Hey, up at this next corner, we’re going to turn left.’ And I say, ‘Oh, OK.’ Then, five seconds later, someone else comes and says, ‘Hey, up at this corner, we’re going to turn right.’ I’m going to forget everything you and I just agreed to and say, ‘OK, we’ll go right.’”

Kramer obviously cannot recall his own mental state, but Dergan sure can.

She remembers Kramer doing nothing but sit on a couch to watch TV all day.

The screen had a “mesmerizing” effect.

“He would sit in front of a TV for six hours at a time without getting up to go to the bathroom or getting anything to eat,” Dergan says. “If you didn’t put food in front of him, he wouldn’t eat. It’s like his brain didn’t know he had to eat. He’d sit in the same spot and not move. It was absolutely insane. A person who’s caring would make sure he was eating and make sure he was taking his medication and would know all the medication he was taking. Not think about herself, and that’s what she would do — ‘Oh, this is my opportunity to go steal.’

“She said, ‘I have the life that I wanted. I don’t have to work and I can spend on daily basis.’”

Whenever a movie is made of this all, no doubt, Anna Dergan will be cast as the hero.

Rightfully so, too.

Out of that Bears trip, Dergan became… suspicious. She saw the Amazon boxes piling up in front of Kramer’s house and was confused. Kramer never ordered anything. And when she sat down to help him with some medical bills, Kramer told her that he couldn’t write a check because his account was overdrawn. Huh? This made zero sense to Dergan. When she checked Kramer’s bank records, she was shocked to see north of $46,000 in spending.

On Oct. 19, 2016, Dergan alerted the Sheriff’s Department to start an investigation.

On Oct. 21, the detective on the case — David Lingscheit — interviewed Kramer at the brain center. Of course, it didn’t matter what anyone said to Kramer himself. Dergan. His sister. His son. His best friends. Everyone close to the ex-QB told him straight-up — Cortney is stealing from you! — and he’d hardly react. Lingscheit even reported that Kramer showed no emotion which, to him, was proof that he lacked the capacity to make financial decisions.

When Kramer filled his friend Robert in, he was extremely nonchalant about that initial chat. As if this was nothing, he told Robert the detective would find out who took the money and get it back.

“That is not a normal reaction,” Dergan says. “The detective told him something and he moved on to something else. His attention span was only what’s in front of him. In one ear out the other.”

Kramer filled Baird in best he could and, you guessed it, Kramer then called Lingscheit back to stop the investigation.

“Not knowing his contact info,” he adds, “who do you think dialed that number?”

Knowing Baird was behind this, knowing Kramer was in this mental fog, the detective pressed on. And not long after, a letter from Wells Fargo Bank arrived for Kramer which Baird intercepted. Right there, she could see the investigation was still on. The bank was letting Kramer know it was releasing his records to the detective based on a search warrant.

Lingscheit requested a meeting with Baird and on this late November trip to the detective’s office in Chatsworth, Calif., Baird texted Kramer’s ex-wife to say she may need to get bailed out of jail and would pay her back.

She walked in. She admitted to stealing. She was not arrested.

Says Kramer: “She actually admits it. To everything. Stealing $50,000. Forging checks. And she turns around and walks right out. She’s on video doing this. Now, let’s say I’m a murder suspect and I walk in to the lone detective investigating the murder and I go, ‘It was me.’ Am I walking out of that office?”

Still, those around Kramer had a plan. They wanted Kramer to grant conservatorship to his sister, Kelley, so she’d handle his finances. That’d also allow them to kick Baird out once and for all.

That plan then, effectively, blew to smithereens. Again, Baird stayed one step ahead.

On Dec. 22, she and Kramer were married.

There were no friends, no family present. Kramer has zero memories of this day at all. (“All I did was say, ‘Yes,’ he says. “Someone suggested I do something and I said, “OK.”) By getting married, Baird could avoid prosecution and, Kramer admits, her plan “worked perfectly.” She figured the best way to end that investigation was to get hitched and she was correct.

Dillon only found out his Dad got married when he saw the ring on his finger at Christmas a few days later. When both he and Robert told him right to his face that Baird admitted to stealing $50,000, Kramer reacted as if they had just said $5. He even defended Baird. That piece of paper became one hell of a shield. The criminal investigation, indeed, was finished. And no way does it end right there if Dr. Tomaszewski’s evaluation was taken seriously. He wrote himself that Kramer did not have medical or financial capacity.

Meaning, he cannot make a financial decision for himself.

Meaning, he cannot sign a legal document.

You know, like a marriage certificate.

“So, I wasn’t permitted to get married when I got married,” Kramer says. “And all the lawyers knew that. And one specific one, if he didn’t, should have. The other big lawyer who also should’ve known was the deputy district attorney at that time, Belle Chen. She told the detective, who then told Anna, that the marriage muddied the waters. That’s why she didn’t prosecute. If I’m not allowed to get married, legally, how does that muddy the waters? Everybody f----- this up.

“Think about this: Is it legal to marry a six-year-old? No. But you can marry somebody with a six-year-old brain.”

As he puts, Baird was “diabolical” every step of the way.

Adds Dergan: “What better way to maintain the lifestyle you created for yourself, right?”

On Jan. 10, 2017, a conservatorship hearing was held to get Kramer’s finances under control. Here, the detective testified and Baird promised not to be a threat to Kramer. She admitted to unauthorized spending and claimed she quit her job to care for Kramer.

Kramer heard everyone testify from Baird to Lingscheit and, again, hardly reacted.

He still was not himself.

“He was just… there,” Dergan says. “It was like a body going through the motions. It was like he couldn’t hear what was going on. Even though he was there, even though he’s answering, nothing is penetrating to the brain because we all knew Erik would never be that way. Yet here he is with no reaction after all he heard from the detective, from Cortney saying she stole money. We know the integrity and principles he lives by, he’d never…”

Until one day, Kramer was not someone with a six-year-old brain.

Until, he began to wake up.

About a year and a half into this nightmare, his brain started to recover. He describes the feeling as waking up from another coma. One lightbulb started to flicker on in May 2018 when Kramer put a bid in on a house for his new family to move into. The bid was accepted, but the purchase was nixed. For the first time, Kramer mentally hit the brakes and asked, “Why?” This didn’t add up. The reason: He was professionally conserved. A conservator who wouldn’t step in as Baird spent and spent — by this point, she was taking trips around the country — actually did block this purchase.

The reason Kramer was conserved was Baird’s theft.

Granted, Kramer was still working through the cobwebs, but he knew enough right then to want a divorce.

Adds Dergan: “It was, ‘I can’t do something because of Cortney and it has something to do with theft.’”

About one week later, Kramer took a scheduled trip to Chicago for an alumni golf outing where he first made a point to catch up with an old friend who was a team priest for his Bears in the 90s. Kramer isn’t that religious himself but the two became very close over the years. And, right there over dinner, Kramer told a Catholic priest he was going to get a divorce when he returned home.

He can’t help but chuckle today.

“What I actually did,” Kramer says, “was go home and go to jail.”

Bad turned to worse. Any glimmer of daylight in Kramer’s life cracking open quickly slammed shut.

When Kramer returned home to California around 11:30 p.m., he says he told Baird he wanted a divorce. She said she didn’t want one. He repeated he did once more and went to bed. The next morning, June 13, 2018, Kramer woke up at 6 a.m. and couldn’t believe Baird was awake. (She rarely was ever up this early.) He poured a cup of coffee, grabbed the newspaper, walked outside and says Baird followed him out.

She wanted to talk about this whole divorce thing.

“I said, ‘What’s there to talk about?’” Kramer recalls. “She goes, ‘I told you, I’m not getting one.’ I said, ‘Great. Don’t.’ She says, ‘Where are (my daughter) and I going to live?’ I said, ‘You should’ve thought of that before you started stealing from me.’ She goes, ‘I’m not stealing from you.’ I said, ‘OK.’ She stood up and I put my hand on the back of her shoulder and said, ‘Look, would you just go inside.’ And she kind of shrugged my hand off of her and then ultimately did go inside.”

Time passed, Kramer went back inside to make breakfast and, then, started stacking pictures of Baird and her daughter about five feet from the door.

Baird saw this, he says, and started putting them back up.

Which prompted Kramer to start throwing them out the front door. Which prompted Baird to call 9-1-1.

Suddenly, a convoy of cop cars were in front of the house. When one officer asked Kramer if he put his hands on his wife — his brain still foggy, still considering a question in literal terms — he thought back to the moment he put his hand on Baird’s shoulder and answered that, yes, he did. Kramer was cuffed, thrown into a police car and spent a night in jail. Dillon actually went over to the house later that day, asked where his Dad was and, Kramer says, Baird shut the door on him.

Only after Dillon put a Wellness Search out did he discover Dad was in jail.

Looking back, Dergan believes Baird knew her scam was up and in another attempt to stay one step ahead “concocted the whole domestic violence.” It worked. When Kramer was arrested, he didn’t even have a chance to grab his wallet. He later realized Baird took $18,710.44 over a four-day span while, simultaneously, filing for divorce and putting a restraining order on him. An order that prevented Kramer from returning to his own home — he was forced to live in four different hotels over a 75-day span.

And even after Kramer shut off his credit cards, he says that Baird was able to use the domestic violence charge to squeeze more money out of him.

She requested a sum north of $20,000 for relocation expenses post-divorce, Kramer says, after already stating she paid her sixth months in advance.

“Well, she didn’t pay six months rent in advance,” Kramer says. “Stupidly, she left her bank statements on my computer. For about eight months. There’s no $18,000 or $19,000 check going to any apartment complex. What there is, though, are a couple hotels where she and her daughter went away on soccer trips. There’s the $1,000 she paid to her attorney to have her forgery conviction expunged. So, she perjured herself.”

Of course, the domestic violence accusation was publicly humiliating.

The headlines were damning. The headlines were everywhere.

Baird requested nearly $12,000 per month in alimony on Sept. 10, 2018 and the judge granted her only $530 per month. After that, she stopped showing up for hearings.

To this day, Kramer is adamant that the scene depicted was utterly invented.

“If this is a crime scene and I throw something at the victim or the victim’s daughter or I tip over a chair, wouldn’t there be picture evidence of that? There isn’t any. Not only that. In the police report, where the arresting officer says ‘Did you put your hands on your wife?’ and I said, ‘yes,’ he said, in quotes, attributing it to me: ‘My wife and I had an argument over finances that turned ugly and I pushed her.’ Did I say that? Not even close. And then he said when he entered the house, there were household items all over the house, a turned over chair. Where are the pictures for that?”

There was one silver lining through this all. On Jan. 28, 2019, an L.A. judge nullified the marriage.

Of course, this cost Kramer plenty, too. About $125,000 in legal fees.

Finally, in February 2020, Baird was arrested and charged with 12 felonies including counts of elder abuse, identity theft and forgery. In lieu of this, the domestic violence charge was dropped… not that the news made a fraction of the national headlines his initial charge did. Nobody noticed. The damage to Kramer’s reputation was done.

A trial date is expected to be set at the next hearing June 29. Baird faces a maximum 14 years in prison.

Baird is pleading not guilty.

Baird’s attorney’s office declined requests to be interviewed for this story.

What’s most frustrating? This all could’ve all been kiboshed five years ago. The same felonies Baird is being charged with now would’ve been the same felonies back at the time of that sham marriage. The only difference? About $650,000. Kramer knows this all could’ve been avoided if Chen would have stepped in, if the D.A. would’ve realized Kramer was in absolutely no condition to sign that legal document and done something about it.

The No. 1 problem — all along — was that lawyers weren’t treating this as a medical issue. There is no theft if there is no medical issue. Those closest to Kramer told him repeatedly that Baird was stealing from him and he had zero reaction. Without Dergan’s tenacity on the front lines of a fight Kramer had no clue he was in, heck, this charade likely would’ve played out for years.

As Detective Lingscheit once said, Baird fit a very specific category of thief.

When it comes to dependent adult abuse, perpetrators try to separate you from those around you. They make an emotional connection to a weak target — like that four-hour drive back from Vegas — and systematically push away friends, family, threats. There were times Kramer sincerely thought Dergan and his sister were out to get him.

Anybody could see he was compromised, he adds. All it took was a conversation, a back-and-forth beyond a scripted speech or media interview.

Yet the authorities who should’ve been protecting Erik Kramer hung him out to dry.

“One particular lawyer who got involved in the conservancy part, he made my aunt and sister out to be (evil), like, ‘They are trying to overtake your life, Erik. They’re trying to overtake your finances, annul your marriage. What they’re doing is bad and when the judge hears you speak in this trial, all of what they’re doing will go away, and you’ll go back to living your life again.’ They are the very people who are trying to help me against the thief.

“He’s supporting the thief! Are you f------ kidding me?”

His voice picks up. His eyes widen.

It wasn’t just Baird who stole money. The legal system ate him up.

There’s no doubt about it: Erik Kramer is squarely in the fight now.

So sad to believe there are those that prey on the vulnerable.

This needs to be an ESPN 30 for 30 today!!