The alter egos of George Kittle

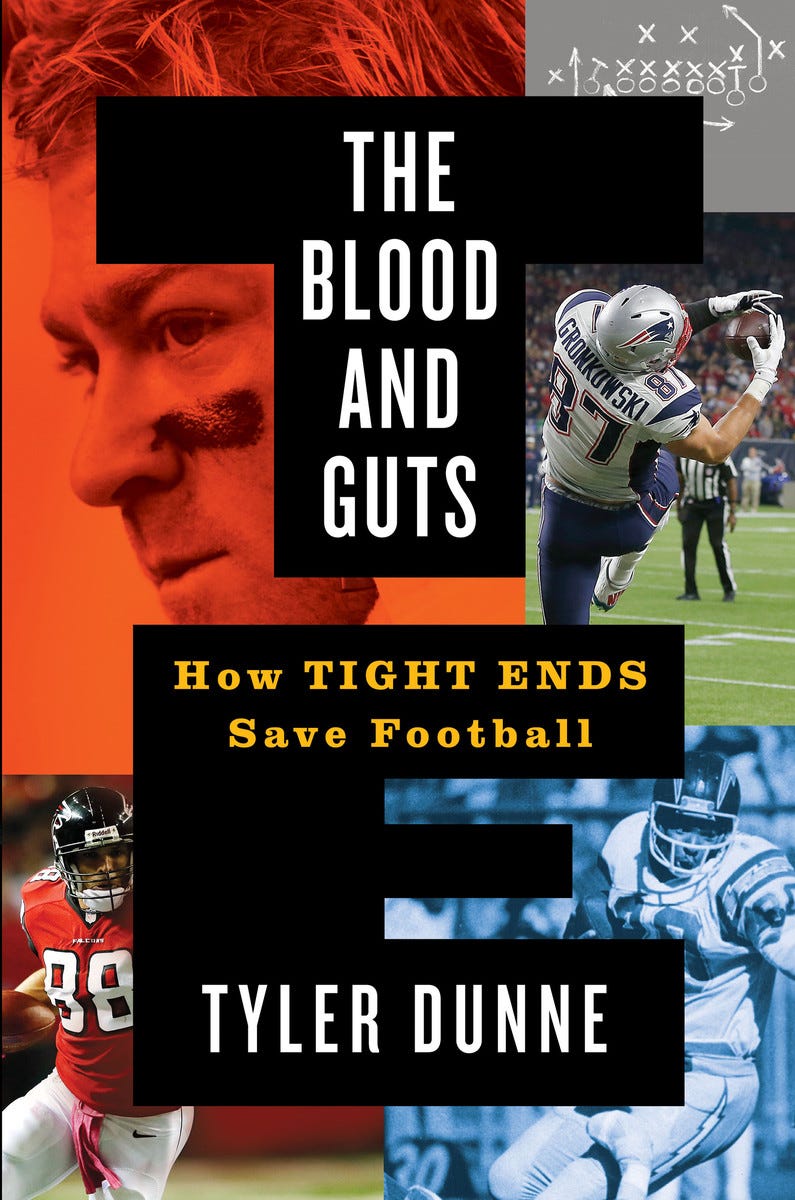

An excerpt from "The Blood and Guts: How Tight Ends Save Football." After all of his turbulence at Iowa, Kittle headed to the NFL to kick a little ass. Here's how he does it.

The following is excerpted from Chapter 15 of “The Blood and Guts: How Tight Ends Save Football.”

To read the entire George Kittle chapter — and learn why the NFL Tight End tells us so much about life itself — you can purchase “Blood and Guts” on Amazon, and everywhere books are sold.

Reprinted by permission from Twelve Books/Hachette Book Group.

The rest of the world was stunned by the sight of a nobody from Iowa bullying small and large men alike from every inch of the field.

In Year 2, George Kittle’s 1,377 receiving yards set a new tight end record. To the naked eye, this number was inconceivable for a player hardly featured in college. He was a henchman of a blocker, too. Kittle? He was not surprised because of how much he had built up his mental toughness after all of the turbulence in college. Schematically, it helped that Kyle Shanahan’s X’s and O’s were similar to everything he saw at Iowa. When the 49ers installed their dizzying outside and inside zone plays, Kittle felt five years ahead of schedule. Dominating as a blocker has a dynamite effect as a receiver, too. He’s proof that it pays to embrace the dreary elements of the position. Kittle would see everyone on defense “tighten up” to stop the run, linebackers tilting forward and . . . see ya. On a quarterback bootleg the next play, Kittle would sneak right past a linebacker for a seventy-yard touchdown.

He was a goofball. OK. But Kittle also created an internal switch to become that same player who smeared defensive ends whenever he damn well pleased.

Through the use of alter egos, he figured out how to turn his feral violence on and off. “Because in football,” he adds, “if you have the flip switched on all the time, you’ll get burnt out.” Specific characters give him specific energies. Back to the classic Batman cartoons in the ’90s, Kittle always saw part of himself in the Joker and still keeps those old-school episodes saved on his phone to binge on his team’s road trips. He is fascinated by the Joker’s devotion to spreading mass chaos. That became his goal on the field. In the Joker’s eyes, his cause was justified — however ill-advised — and Kittle found such passion “inspiring.” So inspiring that the night before his wedding, in 2019, Kittle had the Heath Ledger version of the character tatted on his forearm in all black and white with red lips that became his new reset button.

His wife wasn’t thrilled. Kittle thought she was going to stab him when he told her about the ink plans. He explained how he needed this tattoo for this mental switch, and though she didn’t exactly give him her blessing, she said to go ahead. Kittle spent eight hours in a tattoo chair the day before getting hitched and wrapped his forearm in Saran Wrap the day of. When he took it off, his arm was bleeding terribly.

Of course, it was all worth it. He has channeled the Joker many times over by hammering defenders and cackling atop their bodies. In 2019, Kittle drove Ricardo Allen into the end zone for one soul-snatching pancake. A camera captured Kittle busting into hysterical laughter after somersaulting over the Falcons safety. In 2021, he picked off Philadelphia Eagles linebacker Eric Wilson five yards off the line and, once more, planted a grown man into the grass.

Again, he laughed his ass off.

On his right forearm, Kittle tatted a closeup image of the Master Chief, the protagonist in Halo. This alter ego brings a different energy because the Master Chief is strictly a leader who always finds a way to complete the job. “No matter the odds,” Kittle adds. He’s been fascinated by the full Halo story line, and has read the entire book series because it runs much deeper than anything the video game depicts. The Master Chief could have zero weapons at his disposal and still destroy anything in his path, exactly as any tight end can feel battered and defeated late in the fourth quarter of a tied game.

After climbing one “14er” — a mountain that exceeds 14,000 feet — together in Colorado, father and son got matching tattoos of Longs Peak. That one’s inscribed on George’s left bicep.

And to ensure he’s always on a seek-and-destroy warpath, Kittle also had Godzilla tattooed on the outside of his right forearm.

“I’ve always envisioned myself as a thirteen-year-old kid who’s living his best life,” Kittle says, “and I try to live my life like thirteen-year-old me would always be proud of me.”

The receiving record was nice, but the following season was so much sweeter. San Francisco went 13-3 and advanced to the Super Bowl. To get there, Kittle added to the reel of best plays in tight end history. In a late-season NFC showdown against the New Orleans Saints, his offense faced a fourth-and-two on its own 33 with thirty-nine seconds left. Lined up in a bunch formation to the left side, Kittle caught the ball on a short out route, broke a DB’s tackle and went full Godzilla. Safety Marcus Williams tried to tackle him high (bad decision), gripped ahold of the tight end’s facemask (good try), and was taken on an epic joyride. It took two more Saints defenders to arrive on scene to finally bring him down. The play gained thirty-nine yards in all and, two snaps later, San Francisco kicked a game-winning field goal.

Quite literally, Kittle carried his team to victory. But what most didn’t know was that he had visualized this play the night before. Kittle tried to imagine the craziest play possible. A one- handed catch . . . leaping over a dude . . . getting his legs cut out . . . sticking the landing . . . running into the end zone with another dude on his back. What actually transpired was pretty close. Kittle wore a six-foot-one, 195- pound adult around his neck like a new fashion statement. As the play unfolded in real time, Kittle was not surprised because he has always manifested plays into reality.

The night before games, he sits in an Epsom salt bath, studies the playbook, then visualizes those exact plays he’ll be running.

“If you visualize it enough times,” he says, “when the opportunity arises, it won’t be foreign to you.”

The handwritten letters from his dad only got better over time, too. Ahead of the 2019 NFC Championship, Bruce sent his son a fourteen-pager. George always waits until he’s sitting in his locker at the stadium to read them, too. Many read like a movie script. Bruce once wrote his own Master Chief–themed story that was explicitly related to one of George’s obstacles that season. Through the 150-plus letters (and counting), Bruce somehow keeps it fresh and finds a new way to flip that switch in his son. Through the college days, Bruce had access to unlimited college film as an Oklahoma assistant, so he’d break film down for George and offer pointers. He’ll still detail footwork and hand placement but — in the pros — the letters evolved. Now, it’s all about the “mental game” and “relaxation,” Bruce says.

Meditations. Breath work. So much imagery to ensure his son doesn’t try to do too much because Bruce believes too many guys play far too uptight and lose themselves.

It’s no coincidence that the bigger the moment, the more relaxed George is. He works at this. He has learned how to relax. George has saved all the letters . . . not that they can all see the light of day. So many are spiked with profanity-laced trash talk on various teams — Bruce loved dogging the SEC.

“I say shit in a letter to my kid,” Bruce says, “that I would never say publicly. I drop the F-bomb a lot and say, ‘Motherf--k these people.’”

Of course, those are the ones George loves most because those flip that switch within. Those help him tap into his alter egos.

There’s a twist to his violence, too. This Joker/Godzilla/Master Chief of a tight end superhero doesn’t trash-talk. He isn’t researching an opponent’s reptile business or memorizing a girlfriend’s phone number like Shannon Sharpe. Vengeance doesn’t leak through his pores like it does Jeremy Shockey’s, either. Kittle may play violently but he doesn’t conduct himself violently between plays. Rather, he flips the script. He attempts to disarm opponents with a “cheerful” joy. Anybody can play angry. But in this wacky profession that asks grown men to assault each other, can you play violently 2.3 seconds after chuckling? Kittle forces the nastiest players in the NFL to find out. Against the Los Angeles Rams, in 2018, he told a joke at the line of scrimmage that made star defensive tackle Aaron Donald laugh and jump offsides. This remains one of his personal all-time favorite plays, too.

All talking junk to a guy does, he reasons, is make him want to kill you. He sees no use giving a snarling All-Pro like Donald even more motivation. So, he talks about the weather. He points out the hot dog vendor in the stands. He discusses a new video game. Then he takes a look at one of his tats, harnesses an alter ego, the ball is snapped, and . . . he kicks your ass. Most games, Kittle starts by even telling the colossus across the line who’d like to tear his head off, “Good luck” with an ultrakind, “Let’s stay healthy.” Defensive linemen have told him, in so many words, to shut the hell up and that they will eat him for lunch. He can play that game, too. He has no problem playing that game. But Kittle knows there’s a benefit to acting like Ned Flanders in the middle of such a violent sport.

“A lot of guys like to play the game angry,” Kittle says, “so I try to get the guys to not be so angry and try to make them laugh. That’s always been my MO. Because I can play at that level really well and not a lot of other guys can.”

The result was a modernized Mike Ditka at the best possible time. Right when the position was getting a tad too reliant on finesse— with collegiate offenses shipping 225- pound athletes to the pros in droves — in came Kittle to sock you with a smile.

He applied the same amount of energy to blocking drills with offensive tackles that he did running routes with wide receivers. Specifically, he mastered the separate arts of blocking a 300-pound defensive end, a 245-pound linebacker, and a 190- pound cornerback. All three body types demand strikingly different techniques. He realized that if he learned how to block all eleven players on the field, he’d change the calculus of the entire offense. San Francisco could call plays other teams cannot.

One of his favorite challenges is blocking a 260-pound edge rusher who’s paid $20 million per year to drill the quarterback. Most teams don’t dare exile their tight end to such an island. That’s why so many announcers lambast offensive coordinators on air for having the audacity to block a defensive end with a tight end. “That’s unrealistic!” says Kittle, in his best impression of a color commentator. “Why would you do that?!” His goal is to eliminate such default analysis from the broadcast. Even if it’s only four or five plays per game, Kittle gains a sense of satisfaction knowing that any elite pass rusher he stonewalls at the line is bound to get an earful from their coach in the film room the next week.

Early in his career, ends like Chandler Jones were surprised to get tied up.

That didn’t last long.

“Now, they know that if they don’t bring their A game, I’m going to do everything I can to try to embarrass them.”

This is only part of the George Kittle chapter in “The Blood and Guts: How Tight Ends Save Football.” Here’s the Amazon link to read it all, and B & G is available everywhere books are sold.

Also through these NFL playoffs, we have a special at Go Long…

New readers: When you sign up at the *annual* rate, we’ll be in touch to send you a signed copy of “The Blood and Guts: How Tight Ends Save Football.”

Current subscribers: Gift an annual subscription to a friend, and we’ll send a copy wherever you’d like.

Miss Tight End Days at Go Long? Catch up right here:

Stories and Q&As…

What's next for the NFL Tight End? That's up to Kyle Pitts...

'It's a lifestyle:' T.J. Hockenson and why Iowa is the real Tight End U

Frank Wycheck and an inside look at the 'Music City Miracle'

Book Excerpts…

The unrelenting grit of Dallas Clark, Go Long

Inside Jeremy Shockey’s wild Giants tenure: ‘This dude’s crazy,’ New York Post

New School vs. Old. Glitz vs. Grunters. Tony Gonzalez vs. Mike Mularkey, Sports Illustrated

How Mike Ditka changed football forever, The Dispatch

The Rise of Gronk, Buffalo News

Yo Soy Fiesta!, NBC Sports Boston

Jimmy Graham becomes a Saint, NOLA.com

Tears & Beers: How Jackie Smith found himself, The Read Optional