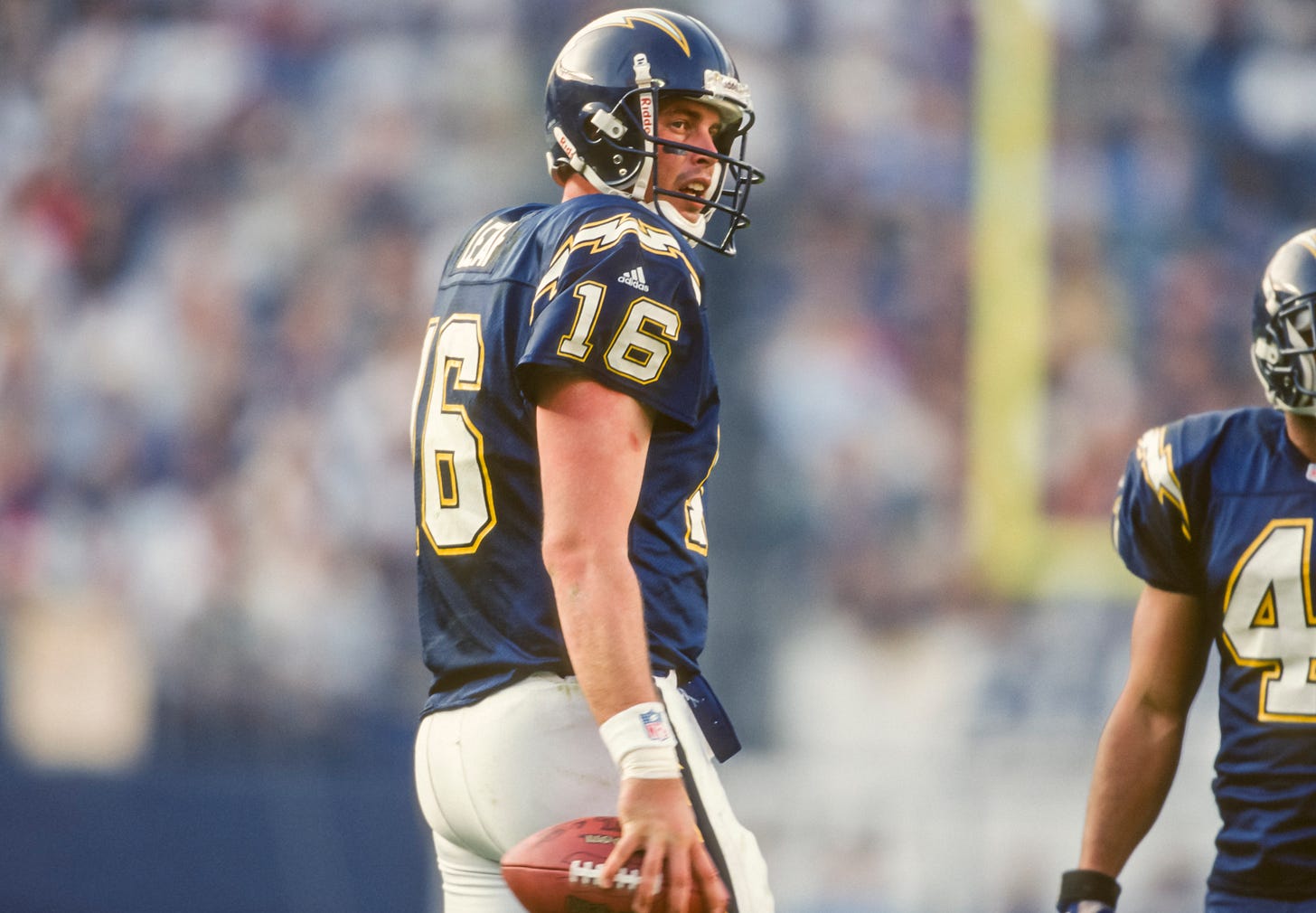

Ryan Leaf wants to save NFL players' lives: 'You're not alone'

We all saw the former QB's reaction to Vincent Jackson's death. Now, an emotional Leaf chats with Go Long on why this tragedy hit close to home, the NFL's indifference and how he is taking charge.

Nobody captured the pain and emotion of yet another NFL player dying quite like Ryan Leaf.

After Vincent Jackson’s shocking death, the former quarterback’s hurt was so real and so raw. Leaf ripped the league for not doing nearly enough to help struggling retirees. While the details surrounding Jackson’s death are still trickling out, Leaf sees the troubling circumstances and cannot help but think there was a way to avoid this.

He would know.

He believes he was in Jackson’s shoes not too long ago.

Of course, Leaf was the former NFL bust taken one pick after Peyton Manning in the 1998 NFL Draft who eventually battled severe depression and eight years of opioid abuse. That addiction led to several legal problems and a 32-month stay in prison. Leaf’s never been shy in detailing this all — he’d break into friends’ homes to steal Oxycodone and Vicodin to feed this addiction. He even attempted suicide, slicing his wrist with a dull knife. He also considered letting his car run in his parents’ closed garage so they’d find him.

But Leaf got out, got sober and started sharing his experiences with the world.

That’s why he even feels “survivor’s guilt” right now and says he easily could have been that player who died in the Florida hotel room. If anyone can relate to what leads players toward any and all dark thoughts, it’s Leaf. He’s convinced he is dealing with the effects of CTE every single day.

Which is all why Leaf has become a go-to hotline of sorts for former NFL players around the country these last 10 days. They’re calling him nonstop. They know what Leaf has been through, saw his video on Twitter and feel helpless and hopeless themselves. Thus, a new life mission for Ryan Leaf. He feels like this, now, is his life calling: To help. You won’t find a more vulnerable retiree than Leaf — he’s the first person to say he’s still working through his post-traumatic issues and, a year ago, he was arrested for battery.

All in all, Leaf is upset at the league for its general apathy and fears, deeply, for all of his NFL “brothers.” Unsure if the league itself will ever help, he’s trying to take matters into his own hands.

Leaf gets into this and all things mental health in this in-depth conversation with Go Long. You can watch the full interview in the video posted above or read the full conversation below. (I’d encourage watching an emotional Leaf for yourself.)

Thanks, all.

Ryan, great to see you. It’s been a couple of years — since we first met there at the JW Starbucks, hanging out. It was great to meet you then, catch up but, gosh, a lot has happened in the world since then, huh?

Leaf: Yeah, it has. What’s been so cool, getting reconnected in the football world the past six years since I got out of prison is the relationships that I’ve reconnected with or formed new ones. I think especially in the communication and journalism world where I think I had some pretty toxic relationships. Or individuals who are in the media now who maybe covered me from the peripheral or had some sort of interaction with me and it wasn’t necessarily good. That’s been really cool to re-develop those relationships, reconnect and I think people are often surprised at the different kind of person I am than maybe what they’ve been told or had seen for so many years. But that’s the cool part of it.

Everybody has this “image.” Everybody has this “reputation” of Ryan Leaf. And then they meet you and it’s not what they expected. When you go into meeting folks like myself, do you run through that stuff in your head? Does it even cross your mind like, hey, this is a chance for them to really see who I am.

Leaf: I don’t think about it. I just interact with somebody as if I would anybody anymore. But there’s one story. Jay Glazer, who covers the NFL for Fox, he started an unbelievable foundation with Nate Boyer called, ‘MVP.’ It stands for Merging Vets and Players. It’s to bring combat vets and former professional athletes together because the transition is so similar. What do you do once you take the uniform off. I remember I had reached out to Nate Boyer after I saw all the work he was doing during the Colin Kaepernick anthem protest and kneeling. I just reached out to him to tell him how much I appreciated his efforts and everything and he invited me to this group. Well, when he went to Jay, to tell Jay he’d like to invite me, Jay’s first response immediately was, “No, don’t! Don’t bring that guy here! What a piece of shit!” And I was like, “Boy, that’s really counterproductive to what his group is supposed to be about, right?” But Nate was like, “Hey, Jay, you don’t get to decide who we save.” So, yeah, that’s the response I expect from people.

And it fits. If somebody comes up and gives me a compliment, I receive it very poorly. My eyes look to the floor. My body language gets bad. Because I’m used to hearing like, “Oh, that Ryan Leaf’s an asshole.” That sounds more like how it’s supposed to be. When somebody says, ‘Ryan Leaf is such an inspiration,’ that sounds foreign to me. Yeah, I don’t think about it that much but I can only envision that’s the interpretation of people.

And with you — with the Players Assistance Fund — when you came out of prison, right, they didn’t want to help you out? You applied for a grant to get your life back together and they said, basically, “You’re a bad egg, a lost cause, we can’t really help you out.”

Leaf: They had helped me out previously, before the prison stint to get some help with some treatment so maybe they thought in their eyes, “We’ve seen this movie before. We’ve tried this before.” I think that’s the line they used: “We’re not going to throw good money after bad.” I think they chalked me up as, “This is a guy we tried to help. He couldn’t figure it out. He’s a failure. And we’re going to move on.” That’s unfortunate but it’s kind of the way the NFLPA works, and it’s disappointing and it really puts some emphasis on guys who have gone through this. Guys who’ve gone through some of their programs and been helped by, dismissed by, it’s our responsibility to take up that mantle and try to help my fellow brothers who are struggling now.

Let’s start with that. I hope everybody saw your video out of the tragic news with Vincent Jackson, dying in the hotel room. Some of the details are starting to come out. We don’t know the full story. The chronic alcoholism. The family fears brain trauma. He was reported missing. It’s not good, however you add it up. I just thought you put it perfectly — it’s needed. The league has to do more. There’s more Vincent Jacksons out there. There have been in the past, there will be in the future.

You could’ve been a Vincent Jackson with everything you went through, with your addiction and hitting rock bottom. Just take us through your reaction of the news that Vincent Jackson had died and what raced through your head at that point.

Leaf: It’s incredibly sad. And I was angry. And I had never really done anything like that. I had been open and honest about my story. But I don’t know if I’ve ever really shown the emotionality out of some of the things I go through on a day-to-day basis. For whatever reason, I was incredibly overwhelmed by the way we all found out about it. Right? Alone, in a hotel room, dying. You’re exactly right — it should’ve been me. Why wasn’t it me? It’s a survivor’s guilt that I deal with sometimes because I’m like, ‘He was an exceptional player and he was an exceptional philanthropic man in his community and helping other people.’ Why would he be taken from us at such a young age and I’m still here? There was a lot of emotion that went into it.

And I was hyperbolic in some of the things I said. Of course, the NFL and the NFLPA care. Their actions don’t necessarily represent that. And I wasn’t looking for somebody to blame because, hey, we can’t expect somebody to watch after us for years and years and years after we played a sport and were their employees. But I just felt like there had to be some accountability and, if not, it may have been a call to action to some of my NFL brothers out there.

I think that’s what really was showcased. The amount of former pro players who reached out to me and we’ve started talking and trying to figure out different solutions together — because I think we realize, that old adage: Once somebody shows you who they are, believe them. I think I have more optimism and hope around some of the things they have told me and you forget that the NFL is a propaganda machine. It’s a marketing arm. It’s a money-printing company. Imagine all those things I just said to you and then to think of a young man at 38 years old with a family and so well-respected and such a future ahead of him, alone, dying in a hotel room.

And that was encapsulated in how I said it. I looked into my video camera and just said it. I didn’t think I was going to post it. Sometimes, I talk into that like a journal and then revisit it later. We don’t see enough of our supposed tough football men expressing themselves with emotions. We just don’t see it. That’s what I did.

I don’t know how anybody could watch that and not feel something. It’s so true. It’s hard to compare anything to the military because nothing compares to the military. But there is a brotherhood, there is a bond, there is something special in that locker room. This is your identity. … From the second you get up in the morning to when you go to bed, everything’s structured in that locker room, in the NFL. This is your life. This is who you are. It’s the most violent game on earth. You’re risking so much out there with your best friends. And then, the lights turn off. Then, you’re ejected back into society. There is going to be some post-traumatic effect, isn’t there? The NFL should have some type of transition program, something to help smooth that over.

Leaf: Think of this juxtaposition. Look at the photos of when Roger Goodell announces the draft pick and the smiles and the hugs. The hugs. I told a draft pick one night after talking to him, leading into his first training camp, I said, “That will be the last time Roger Goodell hugs you.” Why isn’t he there on the day you retire? And you walk out? Why isn’t he there to hug you and say, “Hey, thank you so much for what you gave to this company, this brand. We’re here for you. We’re here for you.” It’s almost made me think about that, like, how can we figure out who’s retiring? Maybe they only played one year in their career but how can I be at their doorstep when they’re making this decision? To be there and give him a hug?

So, those are the types of things that have been running through my mind this last week in a half or so. How can we help and be different? Because it’s such a juxtaposition of this huge emotion of getting hugged by the commissioner and when he retires, it’s “Don’t let the door hit you on the ass on the way out, kiddo. Good luck.”

Is it a stretch to say, when you’re not making money for the shield, for the league, you’re not that relevant to the shield and the league?

Leaf: I would definitely believe that to be true. Also, once you walk away from the game, unless something tragic happens, we don’t really hear about you again unless you’re getting into the Hall of Fame about five years later when your name starts being brought up for that. It’s gone and forgotten. Not that we need attention. I think we need a purpose and to know we’re still part of a brotherhood. I feel like I let a lot of guys down because when I’m going through my crap, we don’t tend to reach out. There’s only 27,000 of us ever in the 100 years of football. That’s a crazy low number. It’s not like 27 million. It’s limited. There’s the ability to have a connection between us all through this process.

For those who don’t know, can you take us back to that low point for you, when you could’ve been a Vincent Jackson, when you could’ve been a statistic, when the addiction had its grips in you. What’s that feeling? How did you get into that dark place and how were you able to get out?

Leaf: I was mentally ill, first. I was dealing with clinical depression when I was in my last stop in Seattle. Because I was having such a hard time getting out of bed. I felt sad all the time. I was overweight because I wasn’t training. I felt lazy. And instead of going in and saying all of these things to Mike Holmgren and asking for help, I quit. I thought that was the best way to get rid of all that, right? Now, I’m not going to be judged or have people be overly critical of me or anything like that. But what you don’t get — in particular, my situation, when you were drafted alongside arguably the greatest to ever play in Peyton Manning and I’m considered one of, if not the greatest NFL draft bust out there — my name doesn’t go away. In fact, I didn’t have football to distract me. Now, the noise was louder so I become incredibly depressed. And I was not seeking any treatment for it. And, of course, there was no transition team or help at that moment in the NFL. It was just, literally, “You’re cut. See you later.”

And before I knew it, I was trying to figure out a way to numb that pain. Or, better yet, not feel anything. I was in Vegas for a fight and the MC was announcing celebrities in the audience. They announced Tiger Woods and Charles Barkley and the audience just went berserk and applauded. They announced my name and the whole MGM Grand just booed and hissed and it’s not like that hadn’t happened before. But instead of just hearing that I was an awful football player, my addict brain heard: “You were a terrible human being, too.” So, sure enough that night, an acquaintance of mine offered me some Vicodin and I was going to go in and out of parties with Hall of Famers and Super Bowl champions who I always felt less than and judged. And I took those pills that night and I walked into those parties and didn’t feel any of that.

I had essentially found what worked and that began eight years of taking that slow slide to the bottom all in the search of not feeling or being able to sit in those feelings of feeling less than, feeling sad, all those things that I should’ve learned how to deal with, with some sort of counseling, psychiatry, something like that. I ended up in a place where I was looking up ways to kill myself on Google. Luckily, for me, the sheriff’s department showed up to save my life. I never thought I’d be grateful for spending 32 months in prison but I am. I’m grateful. I don’t recommend it to anybody. I’m extremely grateful because it had me address issues I may not have done had no one noticed, had gone in silence, had gone alone in a hotel room where no one was watching.

So you’re literally searching this on Google? You’re planning this out?

Leaf: Yeah. And I have a scar right here that I see every single day when I look at it, to remind me no matter what kind of good day is going on or good month or good year — and a lot of them have been good for me the last few years — like, hey, unless you keep doing the right next thing, this is where you can go back to. It’s a reminder that’s hard to look at but it’s one that I need to for exactly those reasons. Watching brothers of mine disappear. Because they weren’t able to do that themselves.

A lot of it is the culture of football. The reason I love the game is that violence, is the fact that it is this war of attrition. These are the toughest SOBs on the planet. In the NFL, you’ve got to be tough. It’s so embedded into the fabric of the sport that you just don’t bring this stuff up in a locker room. You don’t talk about mental health. Up until a couple years ago, this conversation isn’t being had anywhere. … How does the culture play into it and not necessarily help guys? Because you don’t want to bring this up to a coach. You don’t want to bring it up to a teammate, to anybody because it’s a sign of “weakness.”

Leaf: That’s the thing. That’s the stigma. It’s not a sign of weakness. We’ve been told this. I grew up in Montana. There’s a cowboy culture. Men in locker rooms, the football culture of tough guys, where you suck it up for the team. It’s also easier to diagnose a broken leg than it is something you can’t see. If you can’t see it, as athletes, that’s tangible evidence that something is medically wrong. If we can’t see it, it’s just conjecture and we feel like that, “That’s crazy. People will just look at us funny.” We’re all hyper-sensitive to criticism as football players. Just watch what the Combine presents each and every year.

Imagine if a player, 10 years ago, steps in front of the mic at the Combine and expresses that he struggles with depression and social anxiety disorder and has had suicidal thoughts. That guy’s draft stock is gone, right? It’s gone. I still think to this day that it would really put a terrible burden on his agent and his PR people and publicist to get a team to give him an honest look if that were true. So, we have to continue to show vulnerability and transparency. We’re seeing it more and more from athletes. Michael Phelps at the top of his game. Kevin Love recently. DeMar DeRozan. Even Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson has talked about it and he’s the biggest movie star on the planet. He talked about his battle with depression.

So that’s all we can do. That’s all we can control. And understand that showing transparency and vulnerability isn’t weakness. It’s actually the strongest thing you’ll ever do, and one of the things I’m most proud of when I see people do it.

It’s about changing the thinking: “It’s OK to not be OK.” And to talk about it. And your brain is a muscle, so you’ve got to work on your brain like you work on anything.

Leaf: Also now, these days, we live in this Instagram world, too where anything that’s posted just shows your best life. That’s not true at all. I try to counter to that. I’ve tried to post my life — real life. Struggling. Because there’s a platform that I have now. I don’t want to give people unrealistic expectations. That may set people up for more failure, like, “This dude went through everything. He seems real happy all the time.” No. I struggle all the time still. It’s still life. I’m a Dad to a three-year-old boy now. I’m worried that I’m going to fail him constantly. How am I going to support him? It’s life. For everybody. It’s the same, it’s difficult. So even though people may be more open when it comes to mental health, we still live in this Instagram world where what everybody sees is what you want them to see and not necessarily what is real.

How much of a contributing factor is the social media boom to depression? It has to be hard to quantify but it can’t help. It’s got to make everything worse.

Leaf: It’s got to make things much more difficult in terms of bullying, being critical of one another, judging, that type of thing. Yeah, I can only imagine. I’ll make a post that’s inspirational in nature and I’ll get thousands of messages back and there will be one negative comment and, for whatever reason, that’s the one I stick on. It’s such a human trait to see the negative rather than the positive. It just takes practice, the understanding of what other people think of me is none of my business. That’s an affirmation I’ve worked on for years now and it’s finally taking a real hold. And not taking yourself super seriously. It’s a serious subject. But I’m not all that important. I’m a flawed human being just like everybody else trying to be better. That’s what I try to live by every day.

So, what can be done then? What can the NFL do to really make some change here? They haven’t been shy about throwing money and supporting other issues.

Leaf: That’s the thing. They’re going to have to do the same. How they jumped in and full-throated put some money behind the social justice reform this year, that’s exactly what else they need to do. What, ultimately, they need to do is look in the mirror and go, “Do we care? Do we really care?” Because if they don’t, they don’t. I’m not going to rage against the machine if they go, “Hey, we’re a violent, money-printing machine. That’s what we do.” It’s gotta be very difficult to systematically not say football contributes to brain damage, yet then turn around and try to help the people who are dealing with brain damage down the line. It runs counterproductive to what they were trying to rail against in the first place. I guess I can’t fault them for it. And it makes it more on us former players — and our responsibility — to be there for one another and not rely on a corporation that simply doesn’t care.

Therefore, it’s on us. Maybe the realization has finally sunk in. There’s been an actual radical acceptance on my part of going, “Oh. What everybody else already knew, I’m slow to the take as usual and just figuring it out because they invited me in and had me as part of the NFL Legends for a couple years trying to make a difference.” And then, when things get tough, they just send me out on my ass.

So, shame on me. I should’ve known better and been more proactive on my part. Just in the last 10 days since speaking out, you wouldn’t believe the outpouring of former players getting in contact. We’re going to make something happen because of this. We’re not going to have Vincent’s and all the other guys’ deaths be in vain when this is all said and done.

It’s just about being honest to me. If the league was just honest and up front. You mention CTE with the violence. Let’s not tell people the game is “safe.” It’s not safe. It’s a violent game. They’ll never do it because they don’t want Moms to be hesitant about letting their seven- and eight-year-olds play, and that’s the future workforce for the league. But if they were honest and just said, “Yeah, there is a connection. Concussions. CTE. It’s a real thing. Here are the risks. You can either take these risks on or not.” I feel like it’s a lie to say this game is safe, unless you made it touch football, it’ll never be safe. There will be concussions.

Maybe this is another example of the league not being up-front, not being honest, not taking on an issue head-on?

Leaf: They’re a private company. Roger Goodell answers to 32 billionaire owners, right? He does their bidding for them. That’s the bottom line. Hey, I’m as guilty as anybody. I’m entertained. I watched the Super Bowl. I watched the playoffs. I needed a distraction. So maybe there has to come a point where I’m just like, “I cannot contribute to that anymore,” and stop doing it myself. If I’m not willing to do that, how am I really not being part of the solution? It’s tricky. It’s hard to love something so much and know that it creates a ton of destruction later in life to their former stars and their families. That’s a hard thing to equate, ultimately, in your mind. It really is.

And we see former players on ESPN, on NFL Network, as general managers. You think “retired player,” you think that. But that’s such a minuscule fraction of reality. In your video, you mentioned talking to someone who was just in the psych ward. Now that you’ve heard a lot from former players who are going through stuff, what kind of world is out there that we just don’t see when it comes to retired players?

Leaf: The ones you see on TV and in coaching and front office jobs, they’re the exception. The rule is, the majority is struggling. They’re resentful of the NFL. They’re fearful of them and the red tape they’ve put in place to stop you from… I had a guy I was working with here this week who is on full disability because he cannot walk. He really cannot function. He’s got to have people drive him. He’s got to have people put his clothes on for him. He has to order food all the time out. So, he’s on total disability and he was applying for a PCF grant — a Player Care Foundation — which is run within the NFL to get a new hip. It was a new hip or a new knee. I can’t remember which one. So, he could walk. That would increase his quality of life a ton because he probably would be able to get place to place easier. He’d be able to dress himself. He’d be able to cook his own meals. And they denied him because he was on full disability.

They almost use one another against one another. Like, “You’re helping him? OK, we’re not going to do it because you’re already helping him.” I don’t get that. I don’t like that there is a panel behind closed doors that makes decisions on the well-being of somebody you’ve never met. You fill out this application and there’s people back there that I don’t really know who the hell they are. All of a sudden you get an email that says, “We’re sorry. We regret to inform you that you have not been accepted for this grant.” That, for me, is garbage. If it’s available and you meet a semblance of the requirements, right? The subjective nature of it is bothersome.

It just comes down to being a human being and caring for people who built the game. There’s a moral obligation here.

Leaf: And I don’t know if it’s just me having gone through what I did. Maybe because I was not empathetic my whole life. I never put myself in other peoples’ shoes. But having gone through everything I went through, I’m super empathetic now. I want to help. It’s what’s changed my life. The foundation of my new life is to service others. It’s the only reason why I’m still here, I think. There has to be a purpose to that. That’s where my mind goes to. That’s where my action wants to go to. And to see it with roadblocks—for people who have looked me in the eye and talked about how much they care about the former player and everything like that. And to go against it when the opportunity presented itself to help, that’s difficult to watch. It makes me incredibly untrusting and resentful and I don’t want to be either of those two things.

I don’t understand why it’s this faraway jury that really doesn’t understand what a guy’s going through.

Leaf: And it had taken a year of back and forth between this individual and the foundation. The red tape and everything that exists, their job is to figure out a way not to pay you. Rather than figure out a way to get it done or to help you. Their job is to figure out a way to rubber-stamp it, “No.” I run a foundation and I’m terrible at it because every dollar that comes in, I’m sending it back out. I do not hoard a dollar. It goes in and somebody calls up, and it’s “I can’t pay for you to go to the treatment but I can pay for the plane that’ll get you to the state that has the treatment facility for you. I can pay for your plane flight.” It comes down to — when they look in the mirror — what is it really about? And I get it. If they believe they’re a violent, money-printing machine of a company, OK, then it’s on us. It really is. Stop, stop, stop the propaganda then. Stop trying to tell us you care or are there for ya. Just get out of our way. We’ll do it. We’re good enough to do what only the 1 percent of the 1 percent of the 1 percent can do. We can mobilize together as long as we know you’re not dangling that damn carrot out there anymore.

Does it come back to the CBA? There’s the union. There’s the league. You guys are kind of squeezed out? There really isn’t a voice, a seat at the table.

Leaf: They can do that. That’s the thing the owners can rest on. They can rest on, “You guys agreed to this,” through the collective bargaining. They’re exactly right. The former player’s voice is never in the room. We have no say in the collective bargaining negotiations. Only current players do. And guess what? The current players making tens of millions of dollars don’t believe they’re going to be 38 years old, alone, dying in a hotel room. They don’t. They do not negotiate accordingly. And, frankly, they don’t listen to us either. They look at me and think, “I’m never going to be like Ryan Leaf. That f------ loser, drug addict felon. That’s not me. I’m not going to be that guy.” So, therefore, they don’t negotiate in kind. I understand it. I was 21 years old. I thought I was going to make $5 million a year for 20 years and play football. I was naïve.

So there have to be more conversations had. (Players) have to know this is life five, 10 years down the road. You weren’t out of the league long when this went down. It was going down when you were in the league, in Seattle. Just going downhill with the depression. The next thing you know, the addiction’s there and you don’t know if you’re going to be alive.

Leaf: Yeah, we have some awesome success stories, too. Darren Waller down in Las Vegas being placed in the substance-abuse program, getting help and reaching his full potential, and really, he’ll have an unbelievable platform to save so many lives because of what he’s been through. That’s a guy. I’m surprised the NFL hasn’t propped him up more. As success. Because that is the epitome of a success story in the NFL right now. If it weren’t for Alex Smith and his comeback, I don’t see a better comeback story than him and what he’s been able to accomplish.

Ryan, let people know: How’s life today for you? How do you get your enjoyment, your fulfillment? You mentioned your son. What’s your day to day like? That’s what mental health is, too — finding a reason to be happy, to get up in the morning.

Leaf: It’s him. I remember when the doctor put him in my arms. It’s an amazing feeling to have this wave of selflessness just overcome you. I knew, from that point on, everything I did was going to have nothing to do with me anymore. It was going to be completely about him. So, that drives me. Don’t get me wrong. I’ve been in treatment centers and prison with many fathers who told me many times that when they got out they were going to do it for their kids. That’s not enough. You have to do it for yourself. If you’re not the best possible version of yourself, you’re not going to be worthwhile to anybody. So, for me, it starts with that. I open my eyes, I pray, I meditate, I exercise, I eat well. I’ve been blessed with the opportunity to work with SiriusXM, ESPN. Traveled this country, speaking out, giving back to other communities outside of my own. I try to be active, play golf, hike, be in nature.

I’m really engaged in the recovery world, especially here in Los Angeles where it’s unbelievable. I work with other people. I’ve worked the steps which I think are a great method of getting through things. I’m making amends for the things I did do and understanding the consequences that come from them. I see a therapist every week. I do co-parenting with my kid’s Mom. I do anger management classes because, hey, I firmly believe I’m living with CTE. And we see how quickly this comes on, how impulsive people get. We’ve heard from wives and loved ones talking about “never seeing anything like it from him before, and all of sudden, boom, snap, he becomes this impulsive, angry, outraged person. Where never in his life has he been someone like that.” And we get demonized as to, like, “This guy’s this, that or the other.” But it’s brain damage. So, I need to learn how to live with it. So that is what my days are about. How to live with this disease in the most healthy and positive way. Understanding that there’s going to be setbacks, that I’m going to be a failed human being when I lay my head down sometimes at night but knowing if I get up the next morning and do the next right thing, I’m most likely going to lay it down at night in a good space.

Sometimes, I can feel incredibly overwhelmed. Just like any other human being. I don’t look for a handout. I don’t look for anything from anybody. I’m accountable for what I do and what I say. That’s kind of my day. I think a lot of times, we just weren’t willing to accept that there’s something wrong with us. I suppose there was always something wrong with us if we were willing to strap on a helmet and run into 300-pounders who were running as hard as they could to throw us into the ground. I assume there was always something wrong with our brains.

You can tell the CTE is there? Obviously, the science isn’t there to just…

Leaf: Right, we can’t diagnose until postmortem. But we know what symptoms look like now. And I have a few of them that are fully exhibited, like mental health. I had a brain tumor, a traumatic brain tumor that was found and removed. Partially removed about 10 years ago. Substance abuse. And anger. I’m a kind, loving person but sometimes I just like snap and get angry over some of the most trivial things. Especially around shame, and that’s the post-traumatic stress for me. Being hyper-criticized growing up in a small town by the media, by the community. Going through that all the way to the NFL. That’s what it’s all about. And when loved ones are hyper-critical of you and your parenting or how you are as a son or as a sibling, that stuff is triggering and you feel this judgement.

Everybody deals with that. I’m just dealing with it on my own terms and trying to do the best I can. I understand others, who are my brothers, are doing that, too. And I want to be more supportive. I want them to know they’re understood. Like, they’re not unique. I don’t want them to feel alone. All of us are out there like this. That’s the bigger thing in all of this: We’re all out there together going through similar things. I want you to know you’re not alone. You’re not alone at all. We’re just like you.” And I’m here to help any way I can. The only problem is, it’s hard to do it by myself.

You’re one guy.

Leaf: Yeah.

Your phone is probably ringing off the hook.

Leaf: I love it. I love it. I love that it is. But then I laid my head down on Sunday morning and I felt incredibly overwhelmed, too. If I didn’t call somebody back in a timely manner, am I just a dick? Am I letting him down? Then, I’ve got to talk to my therapist and she says, “You can control what you can control. Stop taking all this on. This isn’t on you. Do what you can. Stay out of the result. Do what you can.” So, it’s a constant battle. It’s an important one, and one I feel very honored I get to do. It just takes what it takes.

I will say this, though, the NFLPA reached out and we’re scheduled to meet here, soon. But, of course, I never heard anything from the NFL.

Not a word? The league didn’t reach out at all?

Leaf: And doubtful that I will. They don’t care what the hell I have to say. I was a failure in their eyes, so what the hell do they care? It doesn’t matter what I say to them. I will say, the NFLPA did reach out and I don’t know what that will accomplish but I’m more than happy to have a dialogue. That’s for sure.

I’m sure those phone calls aren’t in vain. Make sure you get that rest and take care of you, too.

Leaf: Yeah, it’s important. I don’t know. In this moment with you, speaking to anybody else who’s listening, I want them to know they’re not alone. They’re not. I’m right there with them. I know how precious life is because I probably shouldn’t have mine. And I’m incredibly grateful for it. And I know there’s a way we can help. I just need some buddies to ride with me through this.

Good stuff as always, thanks Tyler, and to Ryan Leaf.

I found that point about former players not being at the table for the CBA negotiations pretty striking. He's exactly right that current players can't project how they'll feel into the future, and may not even consider trying. Seems like an easy and smart thing to fix....

Just thinking out loud, but if Goodell answers to these billionaire owners, wouldn't the best way to get the NFL to actually care about former players' mental health be to get the owners to care? People assume owners are untouchable, and they are definitely living a different life than most, but they are influenced just like anyone else -- by people close to them and personal stories. And I guarantee many all of the owners have some story related to their own, their family's, or their friends' mental health.

Who would be an owner willing to stick his neck out for this cause, and who may have a strong connection to push that, gracefully?