Quintin Morris, football purist

The Bills need to toughen up to win in January? Here's a tight end who will help in every way... one who also knows the sport must be saved. As Morris says: "I want football to be football again."

EAST AURORA, N.Y. — He can vanquish 20 chicken wings. With ease. Usually, Quintin Morris strategically fasts through an entire Monday after playing on Sunday so he can step into Bar Bill and do serious damage in the evening. There’s no fear of bowel bedlam because the Buffalo Bills tight end knows he’ll have the next day off. His stomach can recover on Tuesday.

In Western New York, players don’t only use off days to soothe their aches and pains from the football field. Wings are a lifestyle.

This spring day, Morris orders 10 Honey Butter BBQ and 10 Cajun Garlic Parm. Yet, three stragglers remain on his plate. Holding two fingers a centimeter apart, that’s how much room Morris says he currently has in his stomach and — for now — he intends to keep it that way. He makes it very clear that he could finish but the Bills are also in the middle of offseason workouts. Seventeen wings, with a side of waffle fries, is a fine place to stop.

Which… still sounds like a lot.

He's not worried. The man knows his body.

“You don’t understand how big of a difference these three wings are,” Morris says.

No wing is ever left behind, either. He boxes up Wings No. 18, No. 19, No. 20 for future consumption.

Consider this the latest evolutionary step for another red-blooded NFL Tight End because this is the position that chooses you. Always. As LeBron James highlights play on the television screen behind Morris, we inevitably stumble into a “Who’s the greatest?” debate. Comparing eras is impossible, but why not? He’ll go 1.) Kobe; 2.) LeBron and… MJ? He’s “in there somewhere.” Don’t misunderstand him. Michael Jordan was special. The first of his kind. But whereas viewers said back then that nobody had ever seen an athlete like this, Morris posits, the game is now full of athletic freakshows. Then, he pauses. He thinks back to how aggressive pro basketball was through the 80s and 90s. How driving into the lane vs. the “Bad Boys” Pistons was akin to hurling your body into rush-hour traffic. And Morris laments the fact that the NBA is much softer today.

Like the NFL.

Now, he’s visibly aggravated.

“You can’t really hit hard in football anymore,” Morris says.

He admits the league’s hard left turn puts more years on his life, but Morris abhors this one-way ticket to Flag Football, USA. And it doesn’t matter if the unnecessary roughness penalty is called on the Bills or whoever they’re playing. Suddenly, it looks like he’s been gnawing into lemons. Not wings.

“I hate seeing guys make good hits,” Morris says, “and it’s called back because it looked like it hurt. Any type of play where it looked like it hurt, it’s always a flag. And I hate seeing that. I’m all for player safety, but we know what we signed up for. They know what we signed up for. We get paid pretty well. We understand what we’re getting into. There’s only so many aspects of the game you can change before it’s not football anymore. I like advancing technology with the pads and the helmet. But hard hits? It’s hard to take those out of the game. Those ones with putting your body weight on the quarterback? I don’t even know how to twist my body to make that happen because all of this is happening like this…”

He snaps his fingers three times.

“All these people who do all the science, you come out here and figure out what’s the best way to tackle guys like Tyreek Hill. Try to figure out how to tackle those guys thinking the whole time about ‘How should I hit him?’ It’s… it’s… crazy.”

Morris is a native Texan but he grew up on the Baltimore Ravens. Ed Reed was one of his favorite players. And Seattle’s Kam Chancellor. Their “knockout blows” drew him to the sport. If a receiver wandered over the middle of the field, he paid for it and, to Morris, this was a feature. No glitch. Granted, there’s a line. A point where a receiver is defenseless. But the NFL’s overcorrection is maddening to this 24-year-old. Nothing through this two-hour chat ignites more passion out of Morris than this “scary” siphoning of physicality. (“You might as well have us out there playing 7 on 7.”) For as long as guys remember, they’ve been taught to finish the man in front of them. He loves seeing teammate Dion Dawkins cleanly flatten defensive linemen on film.

Attacking the sport with such ferocity is a necessity. Slow down and that’s when you get hurt.

“Before you know it,” Morris continues, “it’ll just be the quarterback and receivers out there. You’re taking out the O-Line and the D-Line and the tight end. I want football to be football again. You can only change so much, and it’s irritating. That’s why I’m getting so irritated thinking about it.”

And…

“It’s survival of the fittest. You’re trying to take the guy’s job across from you.”

And…

“I’m getting paid to do a job. He’s getting paid to do a job. Somebody has to win. Somebody has to lose.”

This has forever been his mentality. This is how he overcame four broken collarbones. How he cracked the Bills’ practice squad as an undrafted free agent out of Bowling Green. How he was able to walk right into the general manager’s office to see what it’d take to make the 53. One week after this chat, the Bills select Utah’s Dalton Kincaid in the first round of the NFL draft. A wise choice for an offense that must evolve, and another challenge for Morris who represents the Bills’ offensive reality in 2023. Shiny new toys help but — to break through, to win a Super Bowl — the Bills must first look within. It’s incumbent upon the coaches to utilize personnel correctly and for the players to think like Morris between the lines. NFL players do not become tight ends by accident, the crux of “Blood and Guts.” These individuals saving the soul of the sport become tight ends through natural selection. They slay personal demons and possess a very specific set of characteristics that steer them toward this contour of the field.

Here, football remains football.

Nobody at Bar Bill stops to say hello. Quintin Morris, into Year 3, is still an unknown to most locals. He can change that in 2023.

He insists he’s ready.

“When that real opportunity comes — to really have an impact on the team — you’ve got to take it. And run with it,” Morris says. “You never know when you’ll get that opportunity again.”

Go Long is fully supported by our readers. We’d love to have you join our community.

The goal is to deliver longform journalism worth your time. Thank you.

First, the good news. The cracked collarbones never required surgery.

The bad news? All were painful. Extremely painful. And took a long time to heal. One… two… three… four times Morris broke his collarbone and the nights were always the worst. He was forced to sit in his bed completely immobilized and, mid-dream, the most subtle of subtle flinches would trigger a sharp pain through his entire body.

“You cry yourself back to sleep,” Morris recalls.

In junior high, Morris was a rail-thin basketball player on a football field. His clavicle snapped as easily as one of those flats on his plate. On to George Ranch High School in Richmond, Texas, Morris asserted himself as a playmaking receiver on a state championship team his 11th-grade year. His squad went 16-0, won the state title 56-0, and Morris committed early to play collegiately at Bowling Green. A Power 5 school could still extend an offer but that door was slammed shut during the spring ball ahead of his senior year when Morris laid out for a ball and a defender landed hard on his shoulder.

Morris can still feel the Smack! of this second break. He realized what happened instantly.

“In high school, I’d be elevating… elevating… boom. An injury. I was taking off.”

Now, Morris was worried if Bowling Green would even stay loyal. Despite missing half of his senior season, the offer stood.

Morris caught eight passes as a true freshman. Slowly worked his way up the ladder and, into that ’18 sophomore season, he broke his other collarbone during spring ball. Which led to a “real low point” in his life. Morris would see his roommate trudge to practice and wonder if he’d ever shake this injury-prone label. Maybe football wasn’t for him. Morris healed up, returned and caught 42 passes for 516 yards through a three-win season. A new head coach arrived. He switched to tight end and that’s when he grabbed the NFL’s attention with a 55-catch, 649-yard, four-TD season.

With, of course, a fourth broken collarbone.

On a 59-yard catch and run, Morris was caught from behind and fell hard on the collarbone.

“I kind of got up like it didn’t happen. But then you feel it, like, ‘Yep, that’s it.’”

He played five games in the Covid-shortened 2020 season, and headed to the NFL a year early. Earned a Senior Bowl invite. Ran in the 4.5’s at 252 pounds. Through it all, Morris was too passionate about football to give up on football.

Yet when the NFL Draft arrived, 259 picks passed without his name being called.

As the fourth round bled to the fifth, to the sixth, to the seventh, Morris sat on the couch in the living room with his family. It hurt seeing inferior tight ends get drafted but not as much as seeing the faces of loved ones. Expressions that screamed, he recalls, “What’s going to happen?” They played cards as a distraction. And as the draft trudged to its merciful conclusion, Morris’ agent, Tony Bonagura, called to say the Bills were interested in signing him as a UDFA.

Lost in the collarbone madness was one decision fueling pro football hopes — his move to TE.

Like his tight end forefathers, Morris was undersized on the basketball court — he remembers battling “skyscrapers” in the paint. But at tight end, the 6-foot-2 Morris could toy with 5-9 and 5-10 defensive backs. He quickly realized the athleticism needed to dribble coast-to-coast through those guards helped, too. When new Bowling Green head coach Scott Loeffler asked Morris if ever considered switching, the receiver’s mind raced back to everyone in high school saying he should. He resisted initially — much like a young linebacker buried on the Iowa depth chart named Dallas Clark — before, finally, relenting.

Bulking up 20 pounds was fun. Morris already loved to eat.

Now, in the pros, he had a chance.

He didn’t make the 53-man roster as a rookie with the Bills instead opting to stash Morris on the practice squad. The damn team itself spelled his name wrong on his locker-room nameplate — “Quinton” — but Morris didn’t care. He valued the opportunity to face safeties Jordan Poyer and Micah Hyde each day, pissing both off with his tendency to go “100 miles an hour.” The more plays he made vs. Buffalo’s No. 1-ranked defense, the more his confidence grew. And grew.

To the point of needing to say something to the GM himself.

When Dawson Knox broke his hand midseason, Tommy Sweeney was bumped up to the No. 1 unit and — rather than elevate Morris — the Bills gave the roster nod to another tight end on their practice squad, a player the Houston Texans drafted in the third round two years prior: Kahale Warring. So, Morris sought answers. Morris asked Brandon Beane point blank why Warring got the call. “Is it something I’m not showing?” he asked. “What can I do to get on the field?” He made it clear to his boss he wasn’t happy punching in and punching out on the P-squad. He wanted to be part of this offense.

Morris wasn’t demanding anything. He was respectful.

Beane admired his guts. This is what any GM should want from a player.

“I didn’t know which way it’d go,” Morris admits. “I just really wanted him to know, ‘Look, I’m not satisfied with where I’m at. I want to help. I believe I can help. If it’s something I’m doing, let me know so I can work on it.”

The relationship between any GM and any player is essentially a marriage with a one-sided prenup. For all lovey-dovey superlatives espoused publicly, general managers can typically cut bait whenever they please. And GMs almost always favor the player they drafted or the player that cost them millions of dollars over undrafted fliers. Trent Sherfield lived this reality. Long before signing in Buffalo, the wide receiver was a victim of cruel politics under GM Steve Keim in Arizona. The best general managers put their egos aside and grant opportunities to the best players. Such tact can seem cold. In Green Bay, Ted Thompson hardly said a word to players in the hallways. And this GM’s replacement, Brian Gutekunst, is now making the same hard decisions… all while an ornery Aaron Rodgers attempts to rewrite history.

When Morris walked to Beane’s office that day as an undrafted rookie, he was hesitant. But only for a moment.

“I knew I was putting in the work,” he says. “And I just wanted to go in there and say, ‘Hey, show me the film. Because I don’t think you’ll find too many times where I’m loafing around and not giving effort and not doing good in all these spots.’ Obviously, there’s stuff I can work on. I just want to know what it is. If they truly see me helping this team or if I’m just taking up space. They basically said, ‘It’s a marathon, not a sprint. We see you.’”

Morris stayed on the P-squad all year but, as 2021 came to a close, Beane told him to be ready to fight for the No. 2 job in the summer. He’d get his chance. Patience was stressed.

Then, the GM signed O.J. Howard.

The reason Quintin Morris was bold enough to approach Beane is simple: His perspective, his why. No catch, no touchdown, no collision lights his face up this afternoon quite like thinking about his brother dominating the competition in the Special Olympics.

Evan Morris is two years older than Quintin.

“He’s a big brother,” says Morris, with a smile. “He reminds me of it plenty of times.”

His presence is a miracle itself. Evan was born premature at one pound, six ounces. With tubes in his body, he spent the first six months of his life in the hospital. Morris says doctors weren’t sure he’d even be able to walk. Now? He’s possibly the best Special Olympics athlete in the state of Texas. With medals, Quintin adds, that “stretch around the house.” Growing up, Mom and Dad never treated the two any differently. Quintin even didn’t know his big brother had a learning disability until years later.

When Quintin worked out, so did Evan.

When Quintin did his homework, so did Evan.

“They wouldn’t baby him. They wouldn’t baby me,” Morris says of his parents. “And I think that’s benefited both of us over the years and what has made him one of the best — especially in track — one of the best stars in the Special Olympics. Every year he goes and every year he pretty much leaves with a gold medal.”

Lately, it appears Evan belongs on a completely different track. It’s not even a competition. (“Now it’s a big gap,” Quintin punctuates. “A big gap.”) He’s the pentathlon king in Texas, dominating in the 100, 400, long jump, high jump and shotput. Evan has played every possible sport except baseball, and Quintin doesn’t blame him. He’d also quit the sport if he was pelted in the face with the ball. On the chartered bus to Dallas for state track meets, Quintin was right there with Evan and all of the Special Olympic kids. This has always been a family affair for the Morris crew.

“Getting to know those kids? They’re hilarious,” Morris says. “There’s never a bad time on those charter buses.”

Day to day, Quintin knew he needed to be patient and understanding but, honestly, he never looked at Evan as anything other than his Big Bro. Their father, Eddie Morris, once harbored NFL dreams himself and getting the family involved with the Special Olympics quickly became a calling. Now, Quintin is hoping to get more involved with the New York chapter of the organization and it’s probably time for Evan to start kicking butt in states beyond Texas.

They’re looking into competitions that span across the entire country.

Everyone in the NFL is a product of their upbringing. Often, the stories are gruesome. The sight of a body at his doorstep and the feeling of being grazed by a bullet affected Isaiah McKenzie. The sight of a Ford F-150 striking his father head-on and Dad’s body traveling 50 yards forever changed Laviska Shenault. One body rolling up on his front lawn shaped Rachaad White. Then, there’s everything Yannick Ngakoue endured: an abusive father, cockroaches, depression. Such PTSD sticks with pro athletes.

But positivity can be powerful, too. Good memories.

The joy of a brother beaming with another gold medal around his neck.

“There’s days you want to just sit there and make all these excuses for yourself,” Morris says. “And then you see what these kids are battling and they just overcome it. It’s a reality check. He’s not making excuses. I’ve got no room to make excuses. I know a lot of those kids would give anything to be in my shoes. It really is humbling. It’s very inspiring.

“He’s special.”

So, bring on O.J. Howard. There was no need to view this signing as the end of his pro football career.

Howard was the former first-round pick with 119 receptions, 1,737 yards and 15 career touchdowns to his name. Howard was fresh off working in tandem with Rob Gronkowski in Tampa Bay, Super Bowl ring ‘n all. Howard received the fancy press conference upon signing his one-year, $3.5 million contract.

Morris, reeling in $705K, was a smart man. Regardless of how hard he worked, he knew Howard was the proven-and-paid commodity. A bet made by Beane.

“You’re bringing in O.J. Howard to back up Dawson Knox. As we see in the league, it gets real political,” Morris says. “Sometimes, it’s the pride that says, ‘I don’t want to admit that I messed up. So, we’ll just go with it.’”

An older teammate reminded him that there’s 31 other teams in the NFL. Produce and someone will find you. Then, all summer, Morris left no doubt that he was the superior tight end. Coaches repeatedly praised him in meetings. Final cuts were one day away and… son of a. Morris pulled a hamstring. His margin for error was already microscopic and, now, Morris felt the Bills would view him as damaged goods.

Expendable at the worst possible time.

He was demoralized — on the spot—because Morris had witnessed this sad story firsthand. He remembered one minor injury nuking the career of a teammate and tried thinking on his feet. After Morris limped off the field, a coach asked what was wrong and Morris considered lying. He nearly told the coach he was A-OK in an attempt to hide the injury with so much at stake. But this was too painful. Inside the training room, the team’s trainers told him to relax. Knox calmed him down. Position coach, Rob Boras, too. The entire room eased Morris’ worries in assuring him that his body of work would prevail.

And they were correct.

Morris made the team, missed Week 1, and earned the No. 2 tight end job.

He finished with 281 total offensive snaps (second only to Knox), in catching eight of his 11 targets for 84 yards with one touchdown that hinted at his potential. Morris toasted Dolphins safety Jevon Holland from the right slot and, in the end zone, the snow balls rained down. Of course, he was left wanting more. No team in the NFL utilized two tight ends less than the Bills last season. Offensive coordinator Ken Dorsey deployed “12” personnel a staggeringly low 3.7 percent of the time. The league average was 18.1 percent. Now, the argument can be made that 12 personnel should be Buffalo’s base formation.

During this lunch, a guitar riff from Boston synchronizes over the speaker with the cash register dinging, wings sizzling and Morris makes it clear it’s his dream to be a “TE1” one day. His sights are set high. Yet still — speaking eight days before the NFL Draft — he sounds like a man who knows the team is about to add a tight end. He cannot exhale too deeply.

Every year, he says, NFL teams are looking for players to replace. He welcomes all competition.

“If I’m beat out, let it be because he performed better than me,” Morris says. “Not just because of the name.”

Eight days later, the Bills trade up to No. 25 overall for Utah’s Kincaid.

He always wanted to be in a video game. So, to hell with his lackluster Madden Rating of 61.

Morris feeds the ball to himself — often. Flags, outs, mesh routes. And it works! He proudly declares himself one of the best Madden players on the team, which begs the question: Why not play Josh Allen to quite literally show the team’s starting quarterback why he deserves the ball.

“I haven’t worked my way up the ranks to where I’m comfortable enough,” he says with a laugh. “I can go to Beane but it’s different when the ball has to go through him.”

True, Allen is the one making $258 million.

Either way, Morris is confident as ever. This is a player who genuinely enjoys the sport’s wild side. A player whose hard wiring is surely difficult for any outsider to comprehend. (Ear muffs, kids.)

“You want the tight end who can do this, do that, one of those guys we can bring across the middle and he won’t be carted off,” Morris says. “He’ll be able to take it, get back up, and the next play put his hand in the dirt, get his fingers and feet stepped on and still be able to go out there and run around.

“The more you take that away, it’s almost like anybody can go out there and do it.”

He’d know. He lived this. Morris points to one high school hit that rendered him momentarily “asleep” on the field. Then to the cloudy symptoms of another concussion in college. Initially, he had no clue what was wrong. Only when the train raging through Bowling Green’s campus drove him crazy and the lights in the library were blinding, did Morris realize this was a concussion. He was forced to go full hermit, in bed, to wait these symptoms out.

Quite a juxtaposition. Morris says this all the same day Damar Hamlin is cleared to play football.

Of course, his Bills teammate was injured on a routine tackle. One doctor told the team that Hamlin had a better chance of getting struck by lightning than this blow to the chest triggering commotio cordis. Thinking back, that night was “a movie scene.” All Morris heard was the pack of trainers and doctors speaking in code to bring Hamlin back to life. The safety pulled through and, as a result, Morris says the Bills became closer than ever. Allen called Morris the night of that game in Cincinnati just to check in. The tight end didn’t even know he had his cell phone number. Turns out, Allen was calling everyone he could on offense to say he was there if they needed anything. A couple days later, everyone went to the quarterback’s house to hang out. At the facility, players started saying “I love you” to each other unprompted. And “I’m thinking about you.” And, that week, the Bills hardly did any hitting in practice.

Morris had no clue what to expect when Buffalo hosted the New England Patriots on Sunday. He desperately wanted a player to hit him to subconsciously assure himself in the moment: “These pads work.” Many teammates felt the same anxiety.

That’s why Nyheim Hines’ game-opening, 96-yard return for a touchdown was so uplifting. A play NFL owners are hellbent on eliminating in the disingenuous name of #PlayerSafety — the kick return — is precisely what made the Bills safer after one the sport’s most horrifying injuries. Morris had a block on the play that helped eliminate his trepidation. It felt OK to play football again. On to the playoffs, Morris dismisses the notion that the Hamlin trauma affected the Bills. He insists nobody was scared to take the field.

Injuries are already a guarantee. Play scared and you increase your odds of getting hurt.

To Morris, you need to be the aggressor. Twenty-two bodies collide at unique angles 150 times a game.

Adds Morris: “I’ve delivered hits. Taken hits. I’ll probably play until I’m limping around.”

Lost through a busy Bills offseason — and the fan base’s current conniption over DeAndre Hopkins — is that the offense frankly wasn’t tough enough in its 27-10 loss to Cincinnati. They were bullied. Punked. On his Happy Hour appearance, the departing McKenzie said the quiet part out loud in that Buffalo’s offense was not built to win in the snow. His “dome” comments went viral for all the wrong reasons. McKenzie was never talking down to the Cincinnati Bengals. Rather, this was his harsh-but-true analysis of Buffalo’s offense.

As equipped, a unit that averaged 28.4 points per game was bound to wither.

Here’s how Morris interpreted the defeat:

“It was one of those games where you get hit in the mouth early and you either recover or you don’t. I felt like there was never a point in that game where we got that juice again. Coaches always say: ‘Bring the energy, bring the energy.’ Energy’s hard to fake. It’s got to come natural with guys making plays. That game, there wasn’t a lot of it there. Obviously the end result was what it was. It was obviously a slap in the face with the previous runs. Playoff run. Playoff run. Boom, stopped short. Everybody has to go home and look in the mirror. It’d be insanity — we can’t do the same thing and expect a different result. So whatever it is we have to fix? We’ve got to fix it. It seems like we’re pretty consistent getting to the same spot. How are we going to get over this hump?

“I don’t think we ever wanted to go out how we did against the Bengals. We wanted to put up more than a fight than how it looked out there.”

Reinforcements help. Down to pennies, Beane worked the long division all spring to keep the Bills competitive. Damien Harris, Latavius Murray, Trent Sherfield, Deonte Harty, Connor McGovern, O’Cyrus Torrence and, yes, Kincaid all should help. We might look back at this offseason as the GM’s best. But overall? The Bills need to discover a hard edge to get over that January hump. Going for it fourth and 2 would be a swell change on the sideline with the players themselves simultaneously adopting the same killer instinct between the whistles.

This attitude adjustment doesn’t require 1973-like ground and pounding.

Rather, leaning on tough dudes like Morris elevates the Bills in weight class.

He can both attach to the line of scrimmage as an old-fashioned “Y” to bury a defender in the run game and leak into the secondary to catch a deep pass. Intellectually, Morris will keep up. He says he knows Allen’s favorite plays and which routes work vs. which defenses. Those snaps last season also helped him learn how to find “tells” in a defense. Where a defensive end’s feet are pointing reveals so much. Morris won’t get hung up on Chapter 3 as the coordinator turns to Chapter 11 this summer.

He accurately views the position as “a mash-up” of all positions.

Most importantly, he’s still not comfortable.

For years, nobody dreamt of becoming a tight end. Rob Gronkowski wanted to be the next Jeremy Shockey in every conceivable way — from bowling over tacklers to getting all the chicks. Everyone else? The position, indeed, chooses you. The unselfish nature of tight end then binds players together.

That’s how George Kittle’s “TE U” was born.

The Bills tight end room, Morris adds, is “a family.”

“You’re a receiver. You’re an O-Lineman. You have to know all of the protections,” he adds. “So, it’s like you’re a quarterback. You have to know everything, and then you’re probably going to touch the ball the least amount out of the receivers. While they go out for passes and stuff, you’ve got to do the dirty work and pick up all the blocks. It’s a really unselfish position. It’s work, work, work and you get your reward last. Some weeks more. Some weeks less. No guy ever complains. You’re always willing to do what’s best for the team.”

It's taken 60 years but maybe now there are little kids out there who desperately want to be a tight end in the NFL one day.

Morris believes that’s the case. Especially since this position preserves the majesty of the sport itself.

He wants the ball more this season, yet Morris is also for anything that gets the Bills closer to their first Super Bowl title. Motivation is still in high supply.

There’s something cool about seeing a packed stadium of fans on hand to watch you perform. He still remembers attending Houston Texans games in the nosebleeds and seeking autographs at training camp. That’s why he’ll never forget a kid at the airport last season asking “Are you No. 85?” He couldn’t believe it. He wants to make fans proud and — always — Quintin Morris wants to make his brother proud. They were able to spend Christmas Day together last season. Count on Evan flying north with Mom and Dad again to visit again this season.

Chances are, they’ll head to Main Street in East Aurora on a Monday night to devour wings.

Evan, sweating with each bite, will order his hot. Quintin will experiment with new flavors. No wing will be spared.

Want to learn more about this position saving the sport’s soul? The one teams like Buffalo and Green Bay are now valuing as central to their offense?

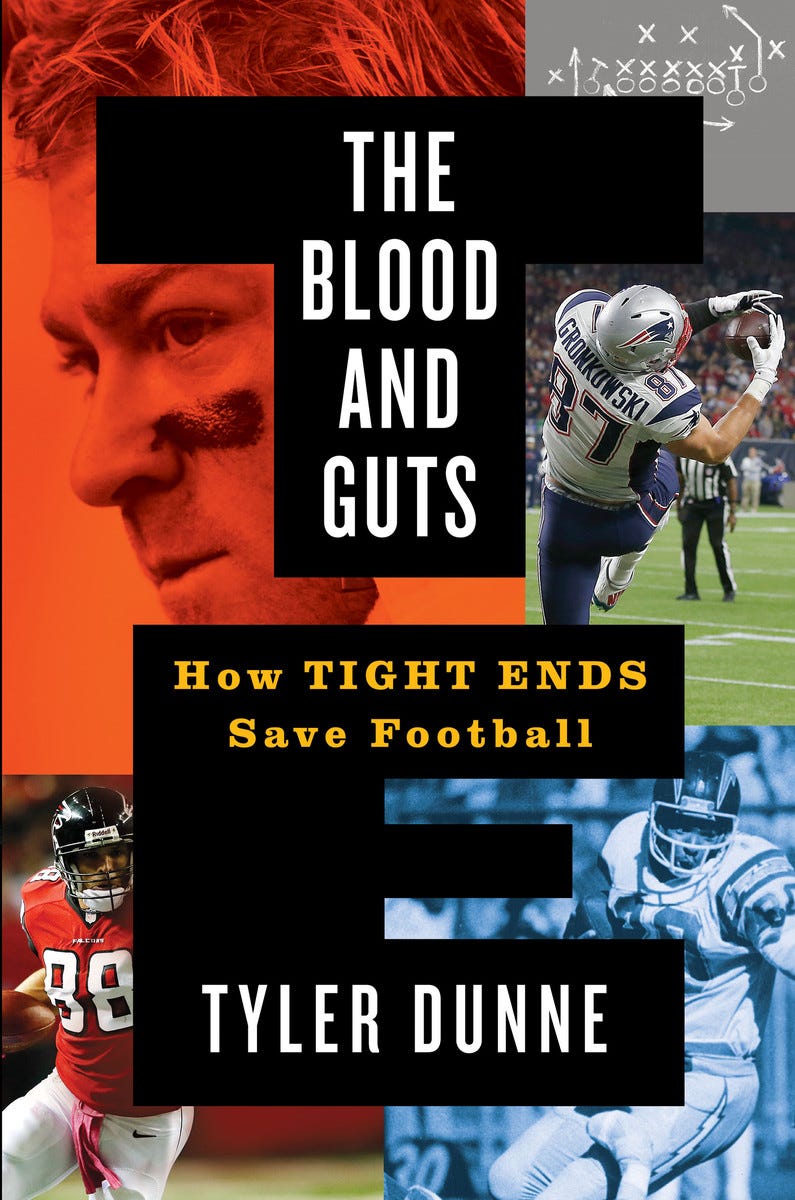

“The Blood and Guts: How Tight Ends Save Football” is available everywhere books are sold, including Amazon, Barnes and Noble and Indiebound.

B & G takes you on a cross-country search for the sport’s soul, from Jeremy Shockey’s go-to bar in Miami Beach to Mike Ditka’s golf course to Tony Gonzalez in Austin, Texas. (Rob Gronkowski has wild stories to share, too.) These tight ends tell the story of pro football and — above all — teach us plenty about life.

Thanks, all.

Also: Miss our first Quarterback Draft? This was fun. Live at Fattey Beer Company in Hamburg, NY, I was joined by podcast co-host Jim Monos and The Athletic’s Matthew Fairburn. We each drafted seven quarterbacks. Watch/listen to that episode right here, or the video below, and feel free to weigh in with your thoughts inside the chat.

It was a fun debate… with high stakes!

And, ICYMI, I met up with Patrick Laird at Cigar City Brewing on my visit to Florida for stories you’ll see over the coming weeks at Go Long. What a curious, fascinating guy. On how we combat screen addiction, free will and the “tribalism” that makes football special:

Part I: Patrick Laird will make you think

TAMPA, Fla. — Our search for conversations with stimulating minds in pro football naturally leads us here, to Cigar City Brewing, where the Jai Alai flows. Usually, it’s a book in Patrick Laird’s hands. Back at the University of California, the running back

Part II: Patrick Laird and why football is a force of good

TAMPA, Fla. — Book to book, he’s constantly pushing his mind in new directions. I’m not sure there’s anyone in the NFL this downright curious. In Part I, Patrick Laird explained the value of reading in the Twitter age, how he beat the odds as a fifth-year pro running back and dove (very) deep into the idea of free will.

Great article! As always, an interesting read