Meet NFL Draft mystery man, Bob Buczkowski

The Al Davis pick sent shock waves through the NFL in 1986. In his latest installment of "The McGinn Files," our Bob McGinn tells the story of the former Raiders defensive end.

The McGinn Files is a series looking back at selected players from NFL drafts since 1985. The foundation of the series is Bob McGinn’s transcripts of his annual predraft interviews with general managers, personnel directors and scouts over the last 38 years. This is the 36th installment of the series, which began in 2019 at The Athletic.

The Los Angeles Raiders’ selection of Bob Buczkowski, a defensive end from Pittsburgh, with the 24th pick in the 1986 draft might well be my choice as the most surprising first-round choice in four decades covering the NFL draft.

When Buczkowski’s name was announced by NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle, shock waves emanated across 27 other draft rooms. He had ordinary size and workout numbers after an ordinary career for an ordinary .500 program. Yet here was Buczkowski, the mystery pick of all mystery picks, going in the first round.

Buczkowski banged around the NFL with five teams over portions of six seasons, starting five of 22 games and finishing with 40 tackles and 1 ½ sacks. He began his career as unknown as a first-round pick could ever be, and ended it as a forgotten footnote in the churn of NFL history.

“I know this sounds strange,” said Ron Wolf, the Raiders’ top personnel man at the time whose friends have said possessed a near-photographic memory. “But this is one guy I can’t tell you anything about. I don’t remember anything at all about him as a Raider. He completely disappears.”

Every player has a story, and Buczkowski is far from the exception. The Pennsylvanian’s chapters would be filled with accounts of his disappointments and regrets as a player, the debilitating injuries and severe health issues that marked his football and post-football life, his convictions in 2007 on multiple counts of dealing cocaine and operating a prostitution ring out of his parents’ home and, in 2018 at age 54, death stemming from accidental drug overdose.

Let’s imagine that Buczkowski would have been drafted where he should have been drafted, which probably is closer to the middle rounds. Then Buczkowski (pronounced Buck-KOW-ski) never would have been selected for inclusion in this series or named by Sports Illustrated’s Paul Zimmerman in 1995 as the biggest bust of all-time among defensive ends drafted in the first round.

Why Buczkowski, known as “Buck” to his friends, wasn’t allowed to play out his career in deserved anonymity can be attributed largely to Al Davis, the Hall of Fame czar of the Raiders, and Earl Leggett, the Raiders’ defensive line coach for almost all of the 1980s. Supported in his folly by Leggett, not only a renowned line coach but a proven, trusted evaluator of collegians, Davis swept aside countering opinions from the majority of his scouts and turned in the card.

“When I was at the Raiders,” said Ken Herock, the Raiders’ de facto national scout whose three tours of duty in Davis’ scouting department lasted 12 years, “I didn’t draft anybody. We tried to recommend guys and all that stuff, but Mr. Davis drafted them.” That certainly was true until at least the later rounds.

Go Long is fully supported by our readers. Thank you for making our longform part of your life. Get all stories delivered to your email inbox by joining our community:

Growing up just east of Pittsburgh in Monroeville, Buczkowski excelled as a two-way lineman at Gateway High School and won the state shot put title twice. In the winter of his freshman year at Pitt, he was begged by the track coach to suit up and help secure maybe a few points in the shot at the Big East meet. He won the event.

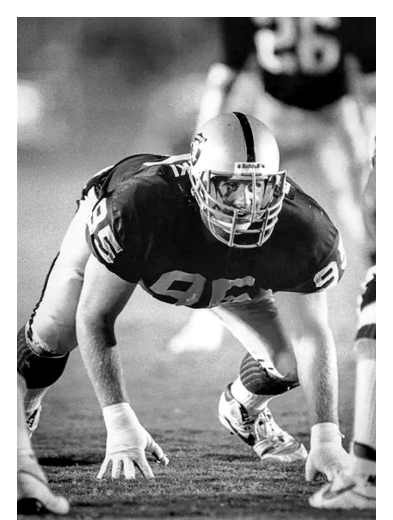

Under coach Foge Fazio, Buczkowski started part-time as a sophomore in 1983, when healthy in ’84 and all of ’85. He posted 133 tackles and 10 sacks in 31 games as Pitt went 16-15-3 during his three seasons. As a junior and senior he lined up as a defensive tackle in a five-man front, according to the Raiders 1986 press guide.

Buczkowski garnered All-East recognition. He was named the school’s defensive player of the year. He wasn’t a captain. Of Pitt’s 13 first-round picks before him, many became stars: Mike Ditka, Tony Dorsett, Hugh Green, Jimbo Covert, Dan Marino, Bill Fralic and Chris Doleman.

National Football Scouting, one of the combines serving NFL teams, gave Buczkowski a final grade of 4.8; a total of 26 defensive linemen were graded higher. Three weeks before the 1986 draft, USA Today’s Gordon Forbes earned a scoop by obtaining and publishing the grades of Blesto, another combine. Buczkowski wasn’t listed among Blesto’s top 27 defensive linemen. In his Scout’s Notebook, Joel Buchsbaum rated Buczkowski No. 23 among defensive tackles; 34 defensive linemen were graded ahead of him.

It should be remembered that the Raiders weren’t members of any combine.

The Green Bay Packers graded Buczkowski as a defensive end. His grade of 5.5, which equated to a third- or fourth-round choice, tied for sixth at the position and tied for 10th among defensive linemen on their board.

Ray Wietecha, a four-time Pro Bowl center for the New York Giants from 1953-’62, scouted the East Coast for the Packers. Buczkowski (6-4 1/8, 271) ran 5.16 on grass for the Packers with a vertical jump of 29 inches and a broad jump of 9-4. He bench-pressed 323 pounds and scored 21 on the Wonderlic test.

In the Packers’ archives from that draft, Wietecha provided the team’s lone evaluation.

For strong points, Wietecha wrote: “Can neutralize the double team and stay on his feet. Inside rush is effective. Good strength, great explosion at times. Quick, quick feet. Over the guard can really penetrate. Disrupts offenses.”

For weak points, Wietecha wrote: “Plays to the level of competition. Against good teams he works harder. Pursuit at times is not what it should be. Inconsistent; needs to be constantly motivated. Has recognition problems at times. Loose, flaky type. When not effective he’s playing too high.”

In his summation, Wietecha came out strongly: “Hugs the line of scrimmage and really takes off. Most always gets penetration … Coaches are not allowing the defensive reels of Penn State (a 31-0 loss in the finale) to be seen … With his attributes should become a pass rusher supreme. With proper coaching, could be a load. Played some outstanding games and some very average games. He can have a fine pro career.”

Because injuries waylaid Buczkowski’s chances in the NFL, it’s notable that the Packers’ report made mention of just one injury for him at Pitt. In spring 1984, he underwent right shoulder surgery.

In all, the Packers ended up giving 67 players a higher grade than Buczkowski. The 68th pick in the ’86 draft would have been situated in the middle of the third round.

Under Dick Corrick, who as director of player personnel was engineering the Packers’ draft under coach Forrest Gregg, the Packers also utilized a system of letter grades for each player. Charley Armey, the team’s West Coast scout at the time, said the system was originated by Tommy Prothro, a head coach in college and the NFL. Armey said Prothro wanted a quick, easy method to identify all his players.

Buczkowski’s letter grade from the Packers was F.

“F is the key,” said Armey, who later expanded Prothro’s system and used it during his years as general manager of the St. Louis Rams. “It means he lacks the athletic ability, speed and agility to play the position. You’ve got to be careful with F grades because there aren’t a lot of F players that are really great players. It’s a tricky grade.”

As for the reaction in the Packers’ draft room when Buczkowski went No. 24, Armey said, “I remember it was a surprise. He was way over-drafted. Guys just reach. For some reason they just fall in love with a player.”

No one could question the Raiders’ level of homework on Buczkowski. In the fall, Angelo Coia, the team’s second-year East Coast scout, handled the school call. Roy Schleicher, a resident of Philadelphia and one of Davis’ one-per-NFL-city network of informants, also filed a report. “He had a real job but went out and did it on the weekends,” said Wolf, referring to Schleicher. “He would have watched him play. We used to go watch them live.”

In January, Davis and his scouting entourage traveled north to Palo Alto, Calif., to watch the practices leading up to the East-West Shrine Game. Buczkowski was participating.

“Al goes to the East-West game,” recalled Herock. “Al would zero in on somebody, and that’s the guy he zeroed in on. He liked him. At the game he said he wanted us to call the offensive linemen he played against and see what they thought of him and ask the coaches what they thought of him. These kids don’t say a lot of negative things. You know, ‘He’s good, he’s a tough guy.’”

Playing right end in the Shrine game, Buczkowski flawlessly executed a power-rush move that sent the left tackle flying. “He did a hump move that Reggie White always used to do,” said Jon Kingdon, who was in his eighth year with the Raiders’ scouting staff. “The arm gets under and he flips the guy. Buczkowski does it. On this play he looks great. Of course, then Al just fixated on the guy.” In the book “Al Davis: Behind the Raiders Shield,” that he co-authored with longtime Raiders scout Bruce Kebric in 2017, Kingdon said: “(Davis) prided himself on being able to determine whether someone was a player just by looking at him.”

Two weeks later, Buczkowski participated in the NFL combine at the Superdome in New Orleans. It was there that Corrick jotted these abbreviated notes on him: “Long arms. Big upper torso. Has a gut. Athletic ability in the 4-square (shuttle run). Some quickness.”

At some point that spring Leggett traveled to Pitt for an individual workout and interview with Buczkowski. A defensive tackle, he was the Chicago Bears’ first-round draft choice in 1957 before going on to a 12-year playing career. He had coached the Raiders’ defensive line since 1980.

Wolf, Herock and Kebric concurred that Leggett was an outstanding evaluator. His cachet couldn’t have been higher, either. The Raiders led the NFL in sacks from 1983-’85 largely because they made the prescient selections of defensive end Howie Long of Villanova (second round) in 1981, defensive tackle Bill Pickel of Rutgers (second round) in 1983, and defensive end Sean Jones of Northeastern (second round) in 1984. All three came from the eastern schools and were unheralded, so it makes perfect sense why Davis trusted Leggett implicitly and himself even more when it came to projecting Buczkowski for greatness on the Raiders’ defensive line.

Following Leggett’s visit, Herock went to Pitt and conducted a private workout of his own with Buczkowski. The Raiders’ time on Buczkowski was in the 4.9s, according to Herock.

“Earl Leggett,” said Herock, who along with Coia in the fall had given Buczkowski grades in the fourth-round range. “He loved him (Buczkowski). I go in to work him, time him, do everything. I said, ‘This is the same fucking guy. I don’t see it. What are we talking about him in the first round?’

“He was a little better athlete than I thought. I didn’t think he had enough burst and speed. They thought he did. I didn’t think he was strong enough at the time. Good worker. He had a couple good things about him but I couldn’t take him in the first.

“Well,” continued Herock, the level of frustration in his voice probably not much different than it was 36 years earlier, “it was like talking to the wall then. Mr. Davis was adamant: ‘This is a first-round pick.’ When Al had his mind set, he didn’t care whoever was on that board. Could be some superstar. He didn’t care.

“Earl liked him, wanted him, was pounding on him. As soon as Earl put the stamp on him, me and Angelo (said), ‘That’s it, that’s who we’re drafting.’ It was over. The scouts were absolutely right.”

Wolf, whose Raiders’ tenure spanned 24 years, admitted that he saw considerable potential in Buczkowski.

“It wasn’t Al here,” said Wolf. “We thought he was going to be one heck of a pass rusher. We had a lot of film to verify that. We had gotten pretty good production out of a couple of guys on the defensive line through the draft. Sean Jones and Howie Long. Thought we had another gem here but it just didn’t work out. It’s a shame he got injured. Maybe he would have been a player. I don’t know.”

After being read the report of Wietecha, who scouted under Wolf in Green Bay from 1992 before his retirement in May 1995, Wolf said, “Ray Wietecha was a pretty good scout. Those were the things that flashed at us. We thought we had a legitimate pass rusher. He had the proper temperament, size, all the things you want.”

The strength of the 1986 was running back, and six went in the 27-man first round. Florida’s Neal Anderson was selected No. 27 by Chicago. Although the great Marcus Allen was only 26 and entering his fifth season, Davis made it clear that he wanted another running back. His long feud, built on jealousy, with the immensely popular Allen was underway.

Kingdon said the scouts recommended Anderson, who went on to make four straight Pro Bowls with the Bears. But Kingdon maintained Davis had no interest in Anderson because he hoped to draft speedy Vance Mueller of nearby Occidental College and Napoleon McCallum of Navy. Both became Raiders late in the fourth round; in extensive careers for the Raiders, McCallum gained 921 yards from scrimmage compared to 911 for Mueller.

“Al came, as did (Bill) Walsh, from the school that it doesn’t matter where we pick them — it matters how they play,” said Michael Lombardi, an executive in personnel for the Raiders from 1998- ‘07. “Al was never scared to take a guy. He was so impatient. He was never going to wait. He never believed anybody in the room who said we could get this guy in the fourth round or we could get this guy in the third round. If you made that promise and you didn’t get him, you were done. You might as well just kill yourself.”

Meanwhile, in Monroeville, Buczkowski was expecting a long wait. In fact, with the draft set to begin shortly after 8 a.m., he almost went golfing thinking there was no way he’d miss that important call. “I thought it would be somewhere between the second and fifth round,” Buczkowski told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

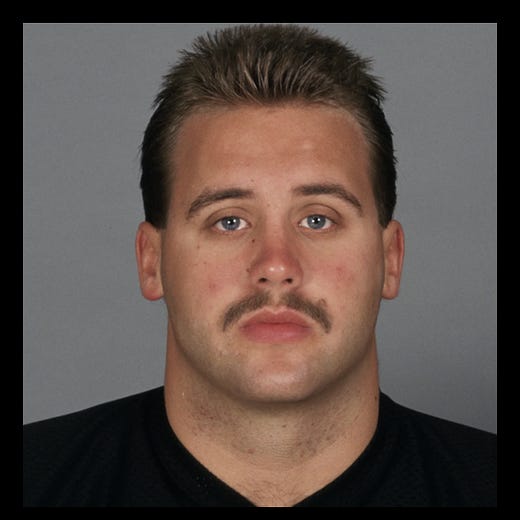

Fortunately, a local television crew arrived at 11 a.m., earlier than advised. The call from Raiders’ headquarters in El Segundo, Calif., came about 11:30. Thus, reporters were there to interview Buczkowski, “decked out in beach attire as he stood on the patio of his parents’ home,” wrote the Post-Gazette’s Steve Halvonik. “He wore sunglasses, a blue T-shirt and matching shorts. His hair was matted with champagne.”

A multi-column photo of Buczkowski hugging his mother, Dianne, provided the lead art on the front of the Post-Gazette sports section on the day after the draft. The headline read: “Oooh, La-La.”

In Raiderland, dumbfounded reporters listened to coach Tom Flores — “He’s not a household name right now. We’ll see if we can make him one” — and, more importantly, Leggett.

“The thing that really impresses you is his quickness off the ball,” the 300-pound Leggett said. “I don’t think Mr. Davis plans for him to start. But he has what Mr. Davis feels fits our mold. We like to do it the Raider way. We like to have time to develop ‘em. We feel he has everything ahead of him.”

Defensive end Lyle Alzado, a two-time All-Pro and 15-year vet, had just retired so Buczkowski was penciled in to back up Jones and Townsend. “Lyle gave us toughness,” said Flores. “And we feel Buczkowski is tough, aggressive and has an ability to be all over the field.”

With a hefty signing bonus headed his way, Buczkowski decided a change in the message on his answering machine was in order. He sang his own rendition of “The Ballad of Jed Clampett,” the theme song of the 1960’s top-rated television comedy series “The Beverly Hillbillies.”

Eric Metz, a longtime NFL player agent, grew up in the same neighborhood as Buczkowski and remained one of his best friends for life. In an interview with the Post-Gazette’s Ed Bouchette after Buczkowski’s death, Metz recited his pal’s revamped lyrics for Bouchette: “The next thing you know ol’ Buck’s a millionaire, the kinfolk said Buck move away from there, they said California is the place you ought to be so he loaded up his ‘Vette and moved to Beverly.”

One day, Buczkowski saw his message light on. The voice said: “Hey king, this is God. Get over here to this facility.” Buczkowski told Metz the caller was Davis. According to Metz, Buczkowski told him, “I never should have left that message. I’m already in trouble.”

Wolf, Lombardi and Kingdon all doubted the veracity of the call from Davis. “That sounds embellished to me,” said Lombardi. “Al was very good with players. He was very, very, very polite.” Metz didn’t respond to interview requests.

Buczkowski’s career couldn’t have gotten off to a worst start. In the post-draft minicamp he twisted his back spinning on a pass rush. Continuing to train during the summer, the back worsened. Instead of opting for surgery, he tried to go at the start of training camp. “He (an orthopedist) said it was a deteriorating disc,” Buczkowski said in July. “I know the pain’s there. Mylocaine, xylocaine, cortisone, I don’t know, I just take ‘em.”

Finally, Buczkowski did have back surgery, then another in August and a third in December. Metz told Bouchette the operations were “botched.”

Buczkowski was optimistic that his back problems were behind him upon reporting for training camp in 1987. At almost the same time, he started getting sick. After practicing for 10 days when he shouldn’t have, doctors diagnosed him with hepatitis. He was sent home, missing the first three games. He was active for four games, playing in two, before suffering an ankle injury that sidelined him until the season finale. In a 1990 interview with Buczkowski, United Press International reported he broke his ankle while jogging.

With Jones traded to the Houston Oilers in April 1988, Buczkowski said he was told he’d have first shot at replacing him. That same month, however, he underwent surgery on both shoulders to repair chronic ligament and bone damage. He missed the minicamps, and with Mike Shanahan having replaced Flores, his security blanket was gone.

“Things started going sour,” Buczkowski described his last training camp with the Raiders in an interview with Curt Holbreich of the Los Angeles Times in August 1989. “I had a bad attitude. I was in so much pain. I didn’t give a crap what happened. That carried over to the coaches. When the time came to make the final cuts, they let me go.”

In another interview with The Times, this soon after being waived, Buczkowski said: “This was the worst I ever played in my life. This was really pitiful. Getting hurt all the time, it gets in the back of your mind … This team’s been nothing but great to me. There are no hard feelings.”

Davis stood by Buczkowski until the end. “After one season Buczkowski supposedly was working out hard,” remembered Kingdon. “Al says to me, ‘Oh, my God, have you seen Buczkowski? He looks like Adonis.’ I said he looks like (pro wrestler) Adrian Adonis, who was a big, sloppy-looking guy.”

The first four picks for the Raiders in 1986 were Buczkowski (two career games, no career starts for the Raiders), cornerback Brad Cochran (0/0), defensive end Mike Wise (50/27) and Mueller (73/5). “God, that might be one of the worst drafts in history,” Kingdon reflected. “Buczkowski was terrible. Brad Cochran never played because of a bad back. Mike Wise committed suicide. And Mueller.”

When asked by Zimmerman what he remembered about Buczkowski, Long replied, “A growler and shouter. Loudest guy I ever heard on the field.”

After spending the remainder of 1988 on the street, Buczkowski was signed by the San Diego Chargers in May 1989 before being cut at the end of training camp. The Phoenix Cardinals signed him at midseason; he played in four games, making one tackle.

Bud Carson, the coach of the Cleveland Browns, sounded impressed by Buczkowski’s minicamp performance in May 1990 after signing him to a free-agent contract. “The jury’s still out on him because he’s had a bad back and played at 300 pounds with the Raiders,” Carson told reporters. “But he gets off the line and races upfield as quickly as anyone we have. So hopefully there will be a resurrection.”

Buczkowski actually avoided injury, playing all 16 games (starting five) for a team that finished 3-13. Carson was canned after nine games. “We were one of the worst teams in all of football that year,” said Lombardi, the Browns’ pro personnel director at the time. “And I don’t remember him being very good, either.” In 1986, Lombardi was scouting for the San Francisco 49ers. “We (the 49ers) were not a fan of Buczkowski,” he said. “I would say he wasn’t even a consideration. Like most people, we had him as a mid-round guy.”

In 1991, new Browns coach Bill Belichick and his defensive coordinator, Nick Saban, deemed Buczkowski as expendable. “He was a one-gap player and we were going to play more two-gap,” Lombardi said. “We needed bigger, physical guys.” In April, the Browns traded Buczkowski to the Seattle Seahawks for a ninth-round draft choice. Flores, the president and GM in Seattle, wanted another look at Buczkowski. When the Seahawks released him in late August, it was the end of the line.

During his years after football Buczkowski tried the restaurant business with some partners. It also was reported that he operated a janitorial service for a time.

In 2005, Buczkowski and his girlfriend were charged in connection with a prostitution ring they were running from the basement of his parents’ home. Using classified ads, they recruited prostitutes to work in their escort business, Buckwild Entertainment, and customers to make it go. The Pennsylvania state attorney general’s office described Buczkowski as “the muscle” and the woman as “the madam.” From February 2003 to June 2005, the business generated about $1 million in revenue. Later, he testified against the so-called “Monroeville Madam.”

In 2007, Buczkowski pleaded guilty to two counts of promoting prostitution, six counts of possessing and dealing cocaine, and other charges. Sentenced to nine to 18 months of jail time, Buczkowski was paroled immediately and placed on house arrest for 90 days in addition to three years of probation.

Later, he was diagnosed with leukemia (in 2014), Type-2 diabetes and chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD). He lived on NFL disability and the generosity of friends including Doug Marrone, the long-time NFL head coach, college head coach and assistant coach. Marrone, from Syracuse, had roomed with Buczkowski at the East-West Game and was also drafted by the Raiders in 1986.

In a GoFundMe post following Buczkowski’s death, his son, Brayden, wrote: “These last few years have been especially tough for our family. My father started experiencing severe memory loss and mild dementia caused by the many concussions he sustained while playing football in the NFL. He also needed to have many surgeries on his back, shoulders, feet and knees. (It) left him in a constant state of recovery, with limited ability to interact with me and my family.”

Buczkowski had been found dead in his home in May 2018. According to the medical examiner’s report, the cause of death was accidental drug overdose. Buczkowski gifted his brain to the Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) Center at Boston University.

Do not miss the next edition of the “McGinn Files,” as Bob McGinn shifts from an all-time draft bust to an all-time draft hit: NFL legend, Peyton Manning. Past McGinn Files features are linked below:

Dan Campbell, Detroit Lions miracle worker: As a tight end, he played through torn labrums and endured 12 surgeries. As a coach, he once asked a player to slap him across the face and. Now, he may be what the Lions have lacked since 1957.

The Rise of Brett Favre, Part I: Before he was a 3-time MVP and a first-ballot Hall of Famer, Brett Favre was just a kid from Southern Miss who could throw a football over them mountains. (He might've been a tick hungover, too.)

The Rise of Brett Favre, Part II: There's never been a player like Brett Favre and there never will be again. McGinn relives the surreal highs & lows with the man himself... and gleans more stories you've never heard before.

Aaron Donald, man amongst boys: He's arguably the best player in football today but the L.A. Rams' monster of a defensive tackle had a ton of doubters out of Pitt.

There is only one Mike Vrabel: His rise is no accident. From college to the pros to taking over the Tennessee Titans, Vrabel was born to lead a football team.

These stories are why i get Go Long!!! Excellent as always

Bob's a great, A-1, superlative writer and journalist. No doubt.

All- pro.

BUT for The McGinn File personality choices he makes, Tyler, PLEASE suggest that he choose one most people remember......Several of Bob's features in The McGinn File have, indeed, focused on past VIP NFL people/athletes.

This choice, Mr. Buczkowski, is a head scratcher....I'll wager that fewer than 10% of your readers remember him.....I do not....and I have CLOSELY following the NFL since the 1970s....and I have no senility/early dementia.....YET (!) Respectfully....thanks for reading.