'It’s incredible:' Super Bowl LX's roots are in Ron Wolf's Green Bay Packers

Eliot Wolf built the Patriots. John Schneider built the Seahawks. Everything we see Sunday night at Levi's Stadium can be traced back to one man: Hall of Fame GM Ron Wolf. Go Long talks to all three.

SAN FRANCISCO — There are pro football teams that do it the right way. Two of them are right here in the Bay Area preparing for Super Bowl LX. Through the 1990s, Ron Wolf’s scouting department became the gold standard. Nor did the Green Bay Packers general manager ever want to hold any of his scouts back. If someone had the chance to climb the ladder elsewhere, he’d do everything in his power to help you. Six of his scouts in all eventually became GMs.

Elsewhere, there are organizations wholly incapable of locating their ass from a hole in ground.

Take Dan Snyder’s buffoonish 24-year stewardship of the Washington Redskins. In 2001, he had John Schneider in his building. The 30-year-old was Snyder’s VP of player personnel. Yet after one 8-8 season, Snyder cleaned house.

Wolf, an endless fountain of football wisdom, thinks back to that time.

“Dan Snyder told me that he made a mistake about John,” Wolf recalls, “because he didn’t want to hire a guy who looked like his paperboy. I always thought that was really an interesting statement.”

Welcome to the Ron Wolf Bowl.

The Hall of Famer’s influence is all over this game.

Go Long is powered by you. Our readers. Thank you for building our community.

One of his former proteges, Schneider, is the GM of the Seattle Seahawks. His son, Eliot Wolf, is VP of player personnel for the New England Patriots. Both have done a masterful job of constructing championship rosters from scratch exactly as Ron did 35 years ago. Arguably no football boss in the Super Bowl era faced Wolf’s challenge upon taking over the Packers on Nov. 27, 1991. The franchise had made the playoffs twice since Vince Lombardi’s reign. Playing in Green Bay, Wisc., was akin to Siberian exile. Free agency, introduced in ‘93, then threatened to render this team nestled in the NFL’s smallest market irrelevant.

Instead, Wolf created an entirely new world over his nine-year run.

Hiring Mike Holmgren. Trading for Brett Favre. Signing Reggie White. His transformation forever lives in NFL lore. At the heart of it all was a scouting staff full of brilliant minds who poured themselves into the profession.

“All those guys really liked football,” Wolf says. “And they bought into the deal. The deal was they were there to make the Packers better. This is always about the Packers, not about us individuals. And they all liked football. They worked really hard at refining their trade. They worked hard at it. Work didn’t bother them. Studying didn’t bother them.”

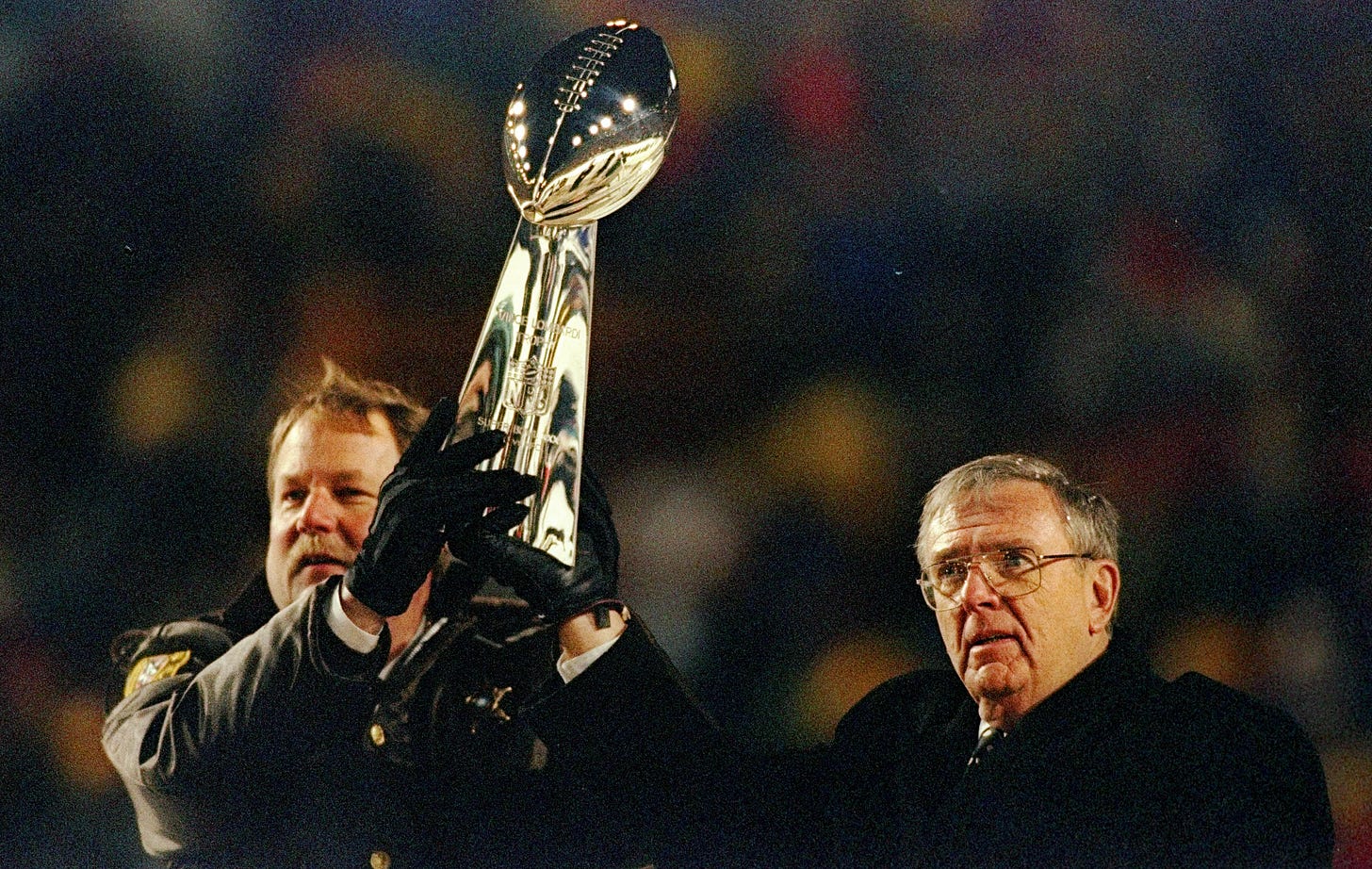

Go Long chatted with Ron Wolf, Eliot Wolf, Schneider and another one of those 90s scouts who became a GM (Scot McCloughan) to learn more. There was no top-, top-secret sauce. Three decades later, the same principles established by the man who resuscitated the Packers fuel Seattle and New England. It’s the work. It’s always been the work. Now, one of those Wolf proteges — his son or his former scout — will cover the Lombardi Trophy with their fingerprints Sunday night at Levi’s Stadim.

The Packers’ standard before Ron Wolf’s arrival was low. To put it nicely. This was an organization toiling in the sewer.

On Day 1, Wolf was provided full authority over football decisions by president Bob Harlan.

Starting from scratch had its obvious disadvantages. Talent was lacking. Morale and hope, too. But he figured out the inherent advantages. Wolf swiftly opened his front doors to all legends from the 60s to feed off of the Packers’ treasured history. Wolf also saw value in geography. Here, there were zero distractions. If he could find players who didn’t like football, rather loved it, the GM knew he had a chance to build something special.

Wolf also devised a completely new evaluation system on players that’d plainly reveal whether you can or cannot scout players.

“There’s no middle road,” Wolf explains. “You either know what you’re looking at or you don’t know.”

Wolf had all prospective scouts evaluate four or five players, read what they wrote, and then kept the ones with the best eye. Green Bay’s personnel department then focused most on NFC Central opponents.

Before any fantasies of winning a title, the GM knew he needed to start with Chicago, Minnesota, Detroit and Tampa Bay.

Wolf loved that Schneider was not afraid. He always voiced his opinion.

Schneider was a key voice in the team’s acquisition of a future Super Bowl MVP. A fourth overall pick in ’92, Desmond Howard flamed out with Washington and Jacksonville before signing with the Packers ahead of the ’96 season. He turned out to be a missing piece. Howard led the NFL in punt return yards (15.1 avg.), touchdowns (three) and then averaged 23.3 yards per punt return, 30.8 per kick return with two more scores in the playoffs. His 99-yard return sparked Green Bay’s 35-21 win over the Patriots.

All avenues were exhausted: the draft, free agency, trades. Once White chose the Packers in free agency, more veterans warmed up to the idea of those negative wind chills up north.

“I think by constant study, constant work, constant stressing the basics of what we’re doing — let’s get better — that’s how it happened,” Wolf says. “Those guys liked what they did. And they were very good at it.”

There was structure to everything the boss wanted. All discourse had a purpose.

Wolf could be intimidating. McCloughan refers to him as “godfather”-like presence.

“He would challenge you to make sure you’re on your game,” McCloughan says. “If you weren’t, he’d let you know. I’ll tell you what, he’d get after coaches and after scouts if they weren’t performing. I’m like, ‘Damn!’ He would cuss like you wouldn’t believe. I’d feel bad with Eliot being in there. He was so young. And I’m like, ‘You’re going to cuss like that in front of your son?’”

“He didn’t play around. He was all about business.”

The standard raised.

Other GMs tended to get enamored by a prospect’s 40 time or vertical leap. Through the 90s, a prospect’s alleged upside became all the rage. Wolf always valued the tape. Whatever a player showed on film — to him — was paramount. Everything else paled in comparison. And in the mid-90s, scouts used “beta tapes” that’d neatly fit into white sleeves for protection. As one draft closed in, Wolf noticed that the team’s running backs coach was all over the place with his grades. Not the end of the world. Coaching is different than evaluating prospects. But Wolf still wanted this coach’s input on a player, and he had a feeling he wasn’t putting in the work.

Wolf slid a $20 bill inside a sleeve of the film and asked the coach to watch three games.

When the coach returned the film, the $20 bill was still present. He wasn’t being courteous, either.

Says McCloughan: “No, no. This guy would’ve taken the $20 bill. He didn’t watch the tape.”

Naturally, the GM let the coach have it.

The standard raised a little more.

“He’d always challenge you,” McCloughan adds, “to make sure you were on your A game.”

Adds Schneider: “That work ethic. How to study. How to communicate. Don’t be a douchebag.”

Granted, Schneider was scared of Wolf. This was his NFL lifeline.

Other scouts couldn’t help but feast off this fear.

With a stern tone, Reggie McKenzie would tell Schneider that Wolf needed to see him inside his office. Schneider would walk down the hallway, into his GM’s office, and… Wolf had no clue why he was there. It was a ruse. Very quickly, the GM grew to appreciate the fact that Schneider was never afraid to speak up. Once while watching Rams film, Wolf asked aloud: “Who’s that guy wearing Dave Elmendorf’s number?” Crickets. He asked again, and Schneider chimed in: “Who’s Dave Elmendorf?” Elmendorf hadn’t played since the 1970s.

Wolf struck the perfect balance of being both tough and compassionate. He wanted everyone on his staff to progress, even if they couldn’t see it themselves. McCloughan had no intentions of leaving Green Bay at the turn of the century. One day, Wolf admitted he was retiring soon and that McCloughan needed to move west to serve as Ted Thompson’s director of college scouting. So, he did. He didn’t ask twice. When the Godfather spoke, you listened.

Now, two kids from the same high school take the sports world’s grandest stage.

Schneider graduated from De Pere Abbot Pennings in 1989, which merged with two other schools to become Notre Dame Academy in 1990. Eliot Wolf graduated from Notre Dame in 2000.

“Two guys from the same high school in Green Bay,” says Ron, “are involved in the biggest game of the year in the National Football League for the right to be a champion. It’s incredible.”

Schneider essentially served as a babysitter for the 11-year-old at Packers HQ whenever Eliot got out of school. He’d try to wear the kid out, making Eliot run up and down the basketball court doing layups. “He’d be like like, ‘Can we go play basketball?’” Schneider recalls. “I’d say, ‘Yeah, if your Dad doesn’t fire me!’”

Three years after Ron retired, Eliot joined the Packers scouting staff himself and worked his way up from pro personnel assistant to director of football ops from 2004 to ’17 before heading to the Cleveland Browns with John Dorsey. Following Snyder’s spastic decision in ‘01, Schneider returned to Green Bay from ’02 to ’09 and then took over the Seahawks in 2010. When their paths crossed again in Wisconsin, Schneider gave Eliot a true crash course. Dad doesn’t want to take credit for his son’s ascent, saying Eliot had excellent teachers in the likes of Schneider, McKenzie, Dorsey and Ted Thompson.

“He deserves all this himself,” Ron Wolf says. “Because he did it. I didn’t have a thing to do with that. I think those guys that trained him really did a heck of a job. And plus, he’s got such a great personality. He’s fortunate he received his mother’s intelligence and that helps dramatically. And he’s got her personality as well. So we’re both so proud of what he’s done and he can honestly say, ‘I did it my way.’ He did it his way. And that’s tremendous.”

When I ask Ron what distinguishes Eliot as the Patriots’ de facto GM, he cites similarities in how he helped build the Packers.

“It’s about the Patriots,” he says. “Making the Patriots better. Not an individual, that type of thing.”

McCloughan, who rose up the ranks himself in taking over the San Francisco and Washington personnel departments, is not surprised to see Eliot in the big game. At age 11 and 12, he describes Eliot as more of a child prodigy. One scene often played out in their meetings. Ron would ask an area scout about random prospects, an area scout would admit he doesn’t know much about that particular underclassman and Eliot jumped in.

On demand, he’d recite the prospect’s name and hometown.

“Boom, ‘he’s from Biloxi, Mississippi,’” McCloughan says. “He was young, but he knew everything. He’d embarrass the older scouts. ‘How do you know all this stuff? You’re embarrassing me in front of your Dad!’ He was on top of it.

“He loved the draft room. He loved the draft room.”

Of course, nobody had better access to the football mind of the Canton-bound GM than the GM’s son. Eliot Wolf learned a ton through osmosis. He vividly remembers hanging around scouts and hearing them analyze players for hours on end. Dad always stressed the importance of trusting what you see on tape — and truly believing it. But the No. 1 trait he learned from Dad was how to treat people when you’re in a leadership position.

“How to be honest,” Eliot says, “and have some self-awareness, so you can be able to supplement yourself with the areas that you need to improve.”

Looking back, he can clearly see what made this crew of scouts unique. There was a total lack of ego and “job climbing” prevalent in front offices today. No maneuvering, no backstabbing. They simply watched as much film as they could and prioritized the Packers’ success above anything else. That’s how both GMs in Super Bowl LX operate today. Schneider is repeatedly described by colleagues across the NFL as one of the most humble bosses in the business, the kind of guy who’ll treat acquaintances as old college buddies. No GM lasts 16 years running a team high strung. In Seattle, Schneider’s draft meetings are 7:30-to-7:30 marathons, but he finds ways to recharge batteries and keep spirits up. After giving scouts a break to hit the bathroom or grab a sandwich, Schneider queues up a hilarious video to lighten the mood.

Scouts have seen clips from “Caddyshack” and Step Brothers,” amongst other classics.

With a laugh, McCloughan refuses to disclose all details. Only know there were times scouts got into laughing fits and could not stop.

“I guarantee he still does it,” adds McCloughan, who runs his own scouting service these days. “That’s his personality. When it was go time, we’d grind.”

McCloughan heard that old Washington riff between Schneider and Snyder was rooted in his friend refusing to throw Marty Schottenheimer under the bus. The Redskins owner would “dog cuss” the head coach in an attempt to get Schneider to agree with him. Schneider refused to play such political games. Both coach and personnel exec were fired. Things worked out.

One lesson lasts a lifetime.

Operate with conviction at the sport’s most crucial position: Quarterback.

Wolf famously fell in love with a raw gunslinger out of Southern Miss named Brett Favre. With the New York Jets, Wolf desperately wanted Favre in the ‘91 draft, missed by one pick, and then did everything in his power to steal him from Atlanta as the Packers’ boss. Our Bob McGinn examined in full here.

Both John Schneider and Eliot Wolf realize they lived a charmed quarterback life in Green Bay, seamlessly transitioning from one Hall of Famer (Favre) to the next (Aaron Rodgers). That’s not normal. Through their own strong conviction, however, they found their franchise quarterbacks.

In Seattle, Schneider shipped Geno Smith to the Las Vegas Raiders and signed Sam Darnold at $33.5 million per year. The swap was mocked by pundits across the country. Schneider understood that Smith threw a prettier ball, but he was drawn to all of the other stuff. He loved that Darnold — like Favre — was no cookie-cutter quarterback. His parents didn’t send him to a bunch of 7-on-7 camps. Darnold played linebacker in high school and Darnold was a natural leader. Guys wanted to fight for him. He saw a “three-point shooter” who’s never deterred by an interception.

Darnold doesn’t chuck his helmet and act like a baby. He keeps shooting.

Teammates see this and take on the same personality. If the QB is calm, they’ll be calm.

“That’s why Ron Wolf always said you’ve got to go see a quarterback in person,” Schneider says, “to see how they handle themselves.”

In New England, Eliot took Drake Maye third overall in the 2024 NFL Draft. In theory, he could’ve moved that pick for a massive haul. The Patriots were peppered with offers from other teams, but Eliot never seriously entertained them. Unlike Bears GM Ryan Poles, who laughed Maye off the screen, he saw this raw North Carolina prospect making NFL-quality throws.

The more he was around Maye, the more he also viewed him as a quarterback any GM should want as the face of their team.

“It’s all genuine,” Eliot says. “I know he goes up on the podium and he talks about, ‘I don’t care about personal accolades.’ That’s all real. He is all about the right things. He’s all about the team. He’s super competitive. He’s super tough. Obviously glad we have him.”

Football doesn’t need to be overly complicated. All three agree that the reason they’ve managed to win games and get to Super Bowls is an obsession with the craft. Over time, you develop a sixth sense for the type of player you want filling a roster. Last spring, Eliot Wolf helped the Patriots secure a cavalry of free agents who fit Mike Vrabel’s identity. Milton Williams, Carlton Davis, Robert Spillane, Harold Landry, K’Lavon Chaisson, Morgan Moses all fit the new coach’s hard-nosed ethos.

When Wolf watches practice, Vrabel coaches guys on the practice squad with the same energy as the highest-paid players on the team. That’s how he always approached scouting, too. No transaction is too small. Last offseason, the Patriots made a point to add players with “toughness” and “humility” and the result has been 17 wins in 20 games.

When Eliot Wolf scans his 53-man roster, he sees players who’ll fight for the guy next to them.

“That’s pretty unique,” he says. “We didn’t want to bring any assholes in here or guys that weren’t going to be about the team and I think we were able to accomplish that.”

Now, two kids who grew up in Green Bay will fight for the sport’s ultimate prize. It does not matter if one of those GMs resembled a paper boy in the eyes of the sport’s worst owner. Nor does it matter that the other got sucked into the Browns vortex for a couple years.

Ron Wolf will be on hand.

With all due respect to John Schneider, he knows which team he’s rooting for in Santa Clara.

“Blood is blood,” he says with a laugh. “Blood is blood.”

Love it, TD. Thanks!

I've always liked Gute.... but jeez, we coulda had another Wolf.