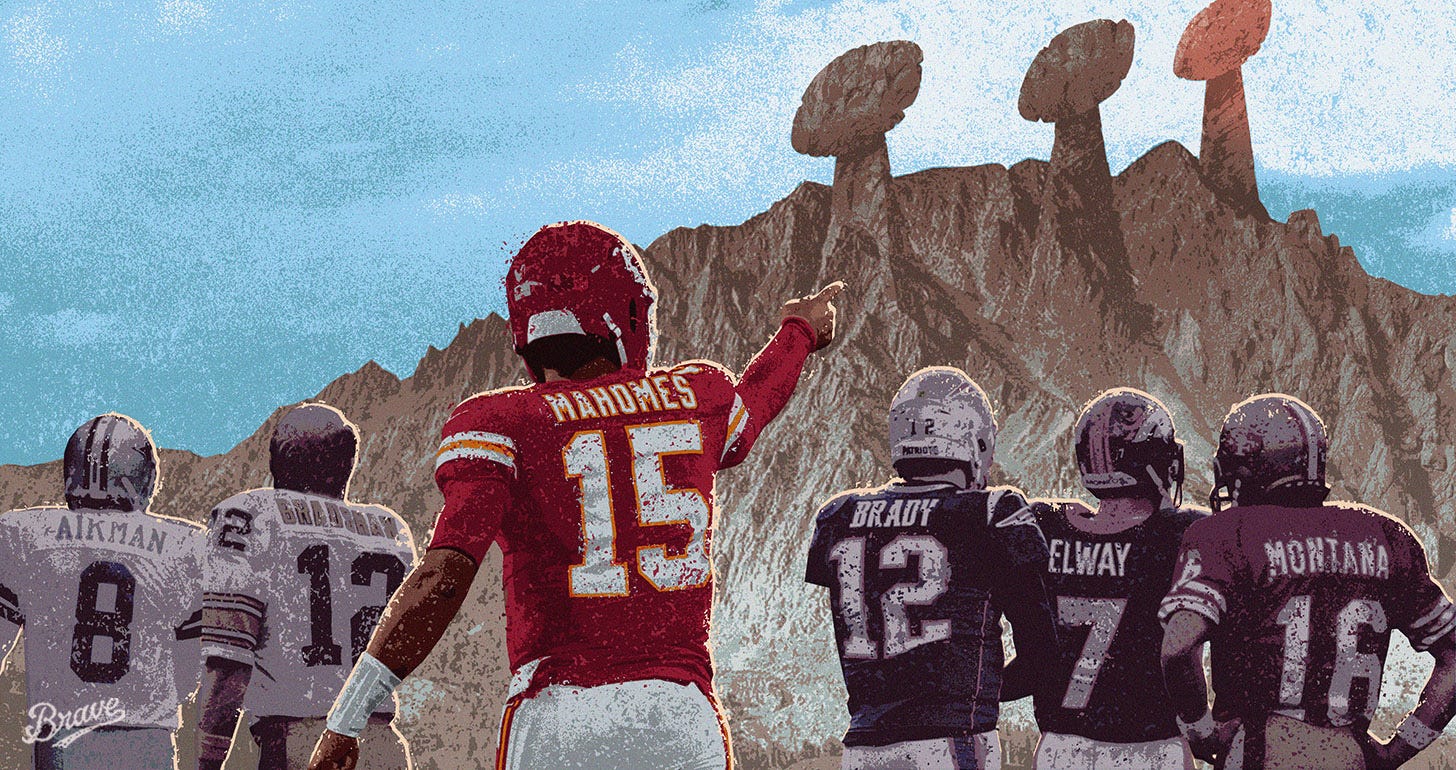

INTO THIN AIR, Part II: Why It’s (Nearly) Impossible to Win Three Straight Super Bowls

In Part II, Michael MacCambridge takes you through history. Eight teams won back-to-back titles but failed to win a third Super Bowl. Why? There are many lessons to learn...

Miss Part I? Catch up here.

By Michael MacCambridge

II | THE HISTORY

“A season is like a lifetime, of things that can happen.”

—Willie Lanier, Hall of Fame middle linebacker

The select group of teams that have had the opportunity to pursue a three-peat includes, by definition, some of the most successful teams and coaches and players in pro football history. There are no impostors in this group. The NFL today is far different than it was when most of these teams repeated, but there are still lessons to be learned from the eight teams that preceded the Chiefs.

Many of these teams suffered key talent losses, in coaching or players or both. Some of these teams were past their prime. Many teams suffered untimely injuries. Some of these teams were brought down by other teams that had been gunning for them for years. A couple of the teams — the ’68 Packers and the ’99 Broncos — lost such key elements of their identity that they never really had much of a chance to defend their title. And in almost every case, the good fortune of the previous two campaigns was unsustainable across a third season.

Each season carries its own lesson.

1968 GREEN BAY PACKERS

Lesson: Don’t lose your legendary head coach and grow old in the same offseason.

With the Packers of 1968, it was all very simple: the titanic presence of Vince Lombardi was gone. More notable than the Packers’ futile title defense of ’68 was that the team had somehow prevailed in ’67, with the legendary Ice Bowl win over Dallas in the NFL title game, before coasting to a Super Bowl II win over Oakland.

“Lombardi’s last Super Bowl, that was strictly will. That was not a great team,” says Ernie Accorsi. “That was his weakest team of his whole generation. They didn’t have anything. Paul Hornung and Jim Taylor are gone, they’re running Ben Wilson and Chuck Mercein. They willed that last title, and a big part of that was Lombardi.”

Though he was no longer coaching, the formidable presence of Lombardi still haunted the building, as he remained the Packers general manger. The new head coach was Lombardi’s longtime defensive assistant, Phil Bengston, who lacked Lombardi’s insistent fire. In David Maraniss’ magisterial biography of Lombardi, When Pride Still Mattered, the tackle Bob Skoronski described Bengston as “just a fantastic guy,” but added that early in the ’68 training camp, he’d concluded that the new coach “didn’t have a chance in hell of succeeding.” If the ’67 Packers had been an aging group, the 1968 Packers were washed — with only one new starter from the veteran team of a year earlier and a starting lineup that averaged 29.5 years of age.

Then there were all the trappings of success. The idea that distractions for Super Bowl champs is some recent development doesn’t really hold up. Jerry Kramer’s memoir of the ’67 season Instant Replay had been a surprise hit, so he was a best-selling author by the time the season got underway, and he’d recall Lombardi walking in the locker room after an early loss to the Vikings, grumbling “Too damn many blue shirts in here. Too many sideburns.”

Kramer had both. “I wore the blue shirts and the sideburns because, between my weekly television show and my weekly book-signing sessions, I cared a lot about my clothes and my physical appearance.”

Kramer would cite myriad commitments pulling the Packers’ veterans in multiple directions: “We all had something going on the side; it seemed like half of us had radio or television shows. I had my TV show, Willie Davis had his, Lionel Aldridge had his, Henry Jordan had his, and Bart Starr had a radio show. We all had a million interests outside football.”

Then there was also the emotional toll on the team. After a 2-3 start, future Hall of Fame tackle Forrest Gregg said, “We have played so many big games in the last few years. We get up for the big ones. But if we don’t start winning soon, all the games will be big.”

That’s what happened. Despite all their missteps, the Packers had roused themselves for a prime-time win over the Dallas Cowboys in October, and dragged themselves to a 5-5-1 record, which was still in contention in the mediocre NFL Central. The key game was a December 1 match-up against San Francisco, in which the Packers took a 20-7 lead. Bart Starr got knocked out of the game in the first half, and his backup Zeke Bratkowski went down in the second half. With the season on the line, the Packers were playing into a strong wind, quarterbacked by nondescript, ineffective rookie Billy Stevens. San Francisco wound up winning 27-20.

They lost again the following week to the NFL champions-in-waiting, the Baltimore Colts. The cover headline chronicling the game in Sports Illustrated read, “A dynasty totters.” NFL Films’ coverage of the game ended with Pat Summerall intoning, “The days of Camelot are over. The king has been dethroned.”

As the clock wound down to end the loss to the Colts, the crowd at Lambeau Field rose for a sustained standing ovation. Everyone knew it was the end of an era. “We had actually died the week before in San Francisco,” wrote Kramer, in his retirement memoir A Farewell to Football, “it was only the funeral that was postponed.”

1974 MIAMI DOLPHINS

Lesson: Don’t take your best players for granted.

After the Super Bowl VIII pounding of the Minnesota Vikings, the Miami Dolphins had won 32 of their previous 34 games, been to three straight Super Bowls and won the previous two. As they entered the 1974 offseason, Don Shula was young and in his imperial prime; Bob Griese, the ultimate game manager, was coming off a Super Bowl domination of the Vikings in which he’d thrown just seven passes, because there was no need to throw more. But the contracts for many of the Dolphins’ best players had run out and Dolphins’ owner Joe Robbie spent the entire winter refusing to negotiate with them.

Then on March 31, 1974, the Dolphins’ three best-known players — running backs Larry Csonka and Jim Kiick and wide receiver Paul Warfield — announced that they had signed futures contracts with the nascent World Football League, which would begin play that June. The trio wouldn’t join the WFL until the 1975 season (by which point the new league was on life support) but the Dolphins were devastated by the signings.

“I am disappointed… shocked… sick… whatever,” said Shula when the news broke. “We were in the unique position of trying to win a third straight Super Bowl and getting everybody back together. Now I don’t know what to think.”

Later the same spring at an awards banquet, Robbie theatrically scolded Shula for being late to the podium. “Don’t ever yell at me in public again,” said Shula, “or I’ll knock you on your ass.” The men went weeks without talking, then entered a summer that would be dominated by the NFLPA strike. There was also a brain drain. Offensive coordinator Howard Schnellenberger had left to coach the Colts, and defensive mastermind Bill Arnsparger had taken over the New York Giants.

Miami was still strong in 1974, going 11-3, fending off a challenge by O.J. Simpson and the Buffalo Bills in the AFC East. But the season exacted a toll, both physically and psychologically.

Their quest concluded with a playoff classic at Oakland against the Raiders. Miami led twice in the fourth quarter, including 26-21 with two minutes left. But Ken Stabler led the Raiders down the field, and threw the winning touchdown, even as he was being tackled by Vern den Herder. The wounded duck pass was ill-advised, and — more lobbed than thrown — pitched into double-coverage. Oakland’s Clarence Davis somehow came down with the ball in the end zone.

“We gave it our best shot, and they won it on a miracle play,” was how Dolphins’ linebacker Bob Matheson described it after the game. Ron Wolf, who was with the Raiders then, concurred. “[Stabler] threw a pass to a guy who couldn’t catch a cold and the guy caught it, in double coverage,” says Wolf. “There was divine intervention there.”

“Trying to get back to that fourth consecutive Super Bowl just wore us out,” recalled defensive tackle Manny Fernandez, in Tom Danyluk’s oral history The Super ‘70s. “We were physically out of it by the time we reached the ’74 playoffs against Oakland. Bill Stanfill, our right defensive end, had a terrible neck problem. I played with ripped and shredded cartilage in my left knee. Bob Matheson was out with a broken arm. Doug Swift had a bad knee. Our starting cornerback Lloyd Mumphord was out. Jake Scott was injured in the [playoff] game and had to leave… The Raiders were lucky to win against a team that had no defense. We were really decimated that day with injuries. Had we been healthy, it would have been no contest.”

Perhaps, though as Accorsi would observe, there was an even larger obstacle facing the Dolphins if they’d beaten Oakland. “They were going headlong into the Steelers, and they were not going to dominate the next era,” says Accorsi. “They were going to have the same problem Dallas ended up having — they couldn't beat the Steelers.”

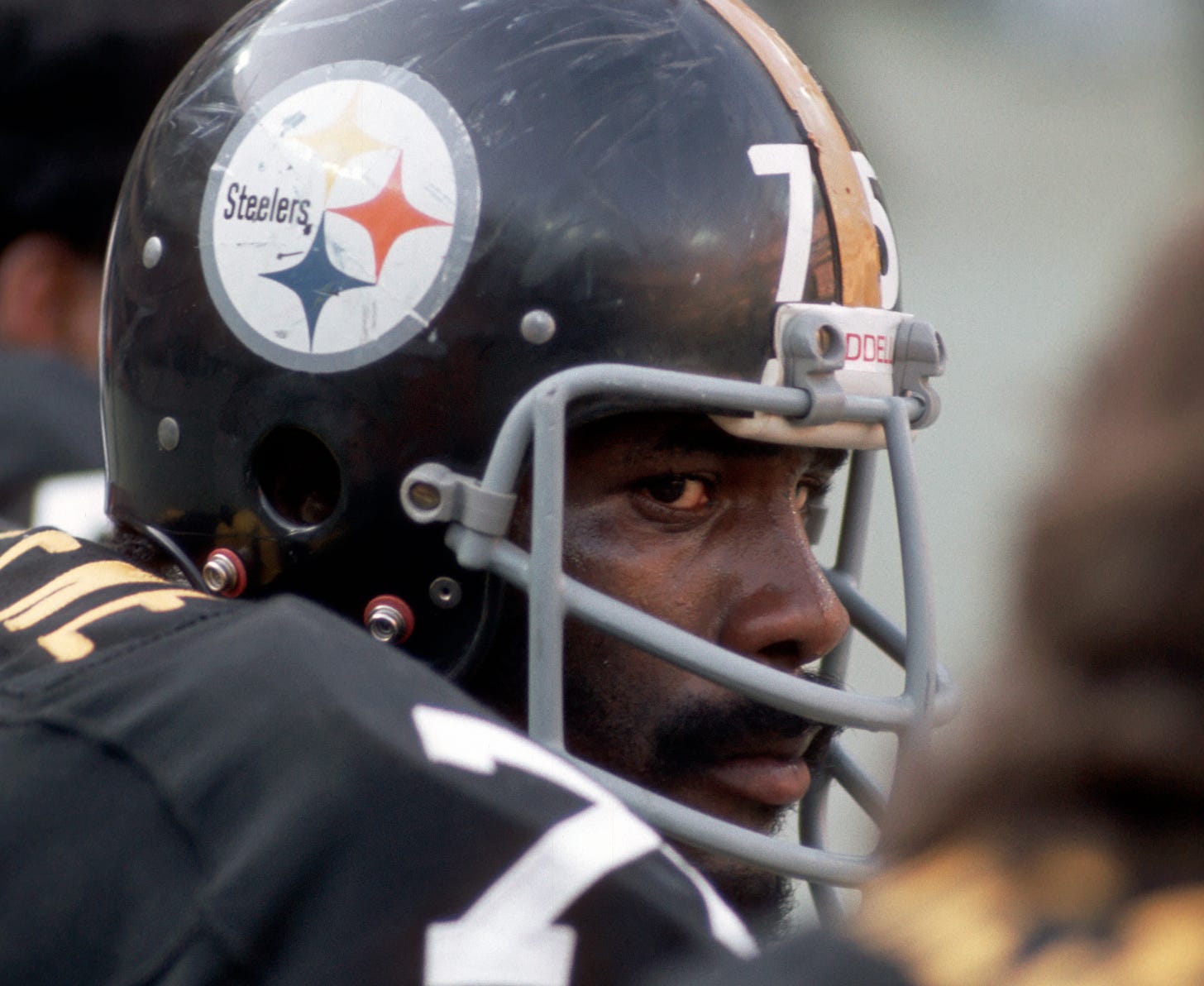

1976 PITTSBURGH STEELERS

Lesson: Don’t get your wide receiver and quarterback concussed in the first month, then lose all your running backs in the playoffs.

As the Pittsburgh Steelers began their quest for a third straight Super Bowl in 1976, they had won 22 of their previous 25 games, and possessed one of the most dominating defenses in NFL history. They would need it.

The Steelers were the Great White Whale to the Oakland Raiders’ Ahab. The Raiders had lost to the Packers in Super Bowl II at the end of the 1967 season, to the eventual world champion Jets in the 1968 AFL Championship Game, the eventual world champion Chiefs in the 1969 AFL Championship Game, the eventual world champion Colts in the 1970 AFC Championship Game, the eventual world champion Dolphins in the 1973 AFC Championship Game, and the eventual world champion Steelers in both the 1974 and 1975 AFC Championship Games.

Pittsburgh opened the ’76 season at Oakland, in the game that still bothers Joe Greene to this day. The two teams were in different divisions, but had played seven times in the previous four seasons, including every year in the playoffs.

The Raiders were consumed with beating Pittsburgh, and the Steelers were equally focused on Oakland. Speaking of his coach Chuck Noll, Jack Ham once said, “The Raiders were enemy number one for him. He never said anything or stuff like that, but you kind of sensed it. Plus, they were always big games They were always in our way to get to the Super Bowl and, conversely, we were in their way, too.”

That opener would shape the entire season. A crucial Harris fumble late in the fourth quarter opened the floodgates, and the Raiders rallied to beat Pittsburgh, 31-28. Late in the first half, Oakland’s George Atkinson clubbed Lynn Swann on the back of the head — far removed from the action on Franco Harris’s long gain — causing a concussion. Atkinson had done the same thing, sending Swann to the hospital for two days, in the teams’ previous meeting, the 1975 AFC Championship Game.

After the game, Noll didn’t mention Atkinson by name, but said, “They went after Swann again. People that sick shouldn’t be allowed to play this game.” The next day, asked about Atkinson again, he was blunt: “People like that should be kicked out of the game or out of football. There is a certain criminal element in every aspect of society. Apparently, we have it in the NFL, too.” That comment in turn prompted a slander lawsuit from Atkinson (funded by Raiders’ managing general partner Al Davis) that would drag through the next offseason.

After two more close losses, the Steelers were 1-3 when they traveled to Cleveland, for what amounted to a back-alley brawl on a football field. Cleveland lost quarterbacks Brian Sipe to a concussion and Mike Phipps to a separated shoulder. But the game would best be remembered for the Browns defensive end Joe “Turkey” Jones picking up Bradshaw and spiking him headfirst on the field like a lawn dart. Bradshaw was diagnosed with a concussion and a sprained neck, and missed the next three starts.

That left the powerful Steelers in dire straits: sporting a 1-4 record in a tough division, its starting quarterback out for extended spell (he’d miss two more games in late November). With longtime backup Terry Hanratty having been taken in the expansion draft, and the mercurial Joe Gilliam off the team, Bradshaw’s replacement by the rookie Mike Kruczek. “Nice guy,” said the Steelers’ receivers coach Lionel Taylor. “He couldn’t throw 25 yards.”

It was going to be up to the defense to keep Pittsburgh in place until Bradshaw healed. “Everybody kind of knew,” says Greene. “Chuck didn’t say, but we kind of guessed it. We had seen Mike in practice, and he had a hard time completing passes.” Kruczek threw zero touchdown passes in six starts, all wins.

With their backs against the wall, the Steelers defense rose to perhaps the single finest extended display in NFL history. They allowed nine points over the next five games, and just 28 total for the balance of the regular season, winning all nine games, five of them by shutout. “It became a serious challenge for us,” the Steelers’ cornerback Mike Wagner said. “How many games could we go without giving up a point? Can we score on defense?” After defeating Cincinnati, 7-3, in a blizzard at Riverfront Stadium, Pittsburgh won out to capture the AFC Central. They would send eight of their 11 defensive starters to the Pro Bowl.

The Steelers routed the AFC East champion Baltimore Colts 40-14 in the divisional round of the playoffs. But Franco Harris and Rocky Bleier — both had gained 1,000 yards rushing during the season — were injured in the playoff win over Baltimore, and wound up missing the AFC Championship Game. Third running back John “Frenchy” Fuqua was banged up and extremely limited; the Steelers relied on reserve back Reggie Harrison.

“I know all the running backs got hurt, but Franco was kind of the heart and soul of that offense,” said Accorsi. “He was just one of those players that was so inspirational without really saying much.”

As Bussert points out, “It’s hard to keep beating good teams time after time after time. Now in that AFC Championship Game they’re playing a team that’s nearly every bit as good as they are, and they have to do it without their two starting running backs.”

The Raiders defeated Pittsburgh, 24-7. “I’m sorry we didn’t have all the weapons in our arsenal,” said Noll. “If we had Franco and Rocky, we would have won the game. As it was, we had to play with our offense at 50 percent.”

But even in the loss, there was something noble about the Steelers, fighting all the way back from their 1-4 start. “I will remember this football season forever,” said Noll. “It is a lousy end, coming back as we did from the start we had. It’s a shame it has to end this way. It tears you up.”

“The ’76 Steelers team had the chance,” says Dungy. “That might have been the best team out of all of them. But then Franco and Rocky got hurt and they have to go to Oakland with no running backs.”

After losing to the eventual world champion in seven of the previous nine seasons, the Raiders finally went on to win their first Super Bowl.

“It didn’t make me feel any better,” says Greene. “But it was their time.”

1980 PITTSBURGH STEELERS

Lesson: Rust never sleeps.

The Steelers team that won Super Bowls following the 1978 and 1979 seasons was a different animal than the juggernaut that won Super Bowls IX and X. The offense — behind the liberalized passing rules that had been prompted, in part, by the suffocating bump-and-run coverage of those Steelers’ teams of the mid-‘70s — had been opened up, with a newly confident Bradshaw firing to two Hall of Fame receivers, Lynn Swann and John Stallworth.

But the defense was aging. The great outside linebacker Jack Ham would describe the team’s fourth Super Bowl in six years — a fourth-quarter rally to beat the Los Angeles Rams, 31-19 — as “kind of like a putt that drops in the hole on the last half-revolution. There wasn’t another revolution in it.”

After the Super Bowl victory party in Pasadena, Chuck Noll pulled his wife Marianne aside to give her his clear-eyed view of the coming year: “Get ready,” he said. “We’re old. And we’re tired. The drafts haven’t been very good. We’ve got some tough years ahead.”

In this, he was prescient. The 1980 season began with predictably outsized expectations, and lots of distractions. At a quarterback meeting during training camp in August, Noll and Bradshaw were interrupted by a sheriff, serving Bradshaw divorce papers from his stormy marriage to the figure-skater JoJo Starbuck.

Then there was Greene’s brainchild, the rallying cry for a fifth Super Bowl ring: “One for the Thumb.” The phrase caught on in Pittsburgh, and soon Greene and his lawyer Les Zittrain had entered an agreement with Kaufmann’s department stores to sell “One for the Thumb” merch. Some saw it as a follow-up to the “Terrible Towel” made popular years earlier by the Steelers announcer Myron Cope.

“Should’ve left that alone,” says Greene. “I was trying to sell the jersey with this group of people. ‘One for the Thumb’ caps, shirts, party paraphernalia, paper plates. It was a bad idea. It was just away from any of the concepts that we had.”

But it was age, more than hubris, that stopped the ’80 Steelers from their three-peat bid. The AFC Central was particularly tough, with the Kardiac Kids version of the Browns and Bum Phillips’ Houston Oilers both splitting with the Steelers, while Cincinnati — which went 6-10 on the year — somehow swept Pittsburgh.

During the season, the attrition — from injuries to Greene, L.C. Greenwood and Franco Harris, among others — became apparent. “Dwight White was gradually losing his place to John Banaszak,” recalled John Stallworth. “John’s a good player, Dwight’s losing that place. Joe is going through the injury that he has. L.C.’s out of the lineup and nursing his thumb. Ham is hurt and so he’s not playing well. Franco’s ankle is bothering him. Rocky is gone now and so guys are starting to come in and they are trying to take that role, and nobody seems to fit.” Pittsburgh lost a crucial late-season game, 6-0, to Houston on a Thursday night at the Astrodome. Bradshaw was sacked three times and threw three interceptions.

Even for the cornerstones of the dynasty, it was clear that the glory days had come to an end. “Age is having an effect,” says Greene, recalling that season. “I was 34 or 35. L.C. was right up there with me. We ain’t 28. And you can’t defeat that. Age and injury and all the other things that seep into your mind.”

1990 SAN FRANCISCO 49ERS

Lesson: Don’t get into a rock fight with the Bill Parcells-era New York Giants.

Of all the teams that vied for a three-peat, it’s possible that the 49ers had the best chance. They certainly had the best regular season.

They had won the Super Bowl under Bill Walsh in his last season, 1988, and then repeated in 1989, under George Seifert. After their second straight Super Bowl, the 55-10 demolition of the Broncos, the victorious 49ers were chatting “Three-peat” in their Superdome locker room.

All that 1990 offseason, they embraced the challenge of trying to win a third straight Lombardi Trophy. “It wasn’t seen as something that hasn’t been done before — it was viewed as something that you are accustomed to doing,” says Eric Davis, a rookie on that 1990 team. “I remember Bill McPherson, my defensive coordinator, standing up in front of the room in one of the very first meetings, and he started talking about certain guys that were going into their third year and he said, ‘You guys don’t even know what it's like to not win the Super Bowl. No reason to start now.’ So that's the way it was discussed. It wasn’t, ‘We’re trying to do something that history says can’t be done. It was more of, ‘This is what we do, this is who we are, this is how we prepare every single day. So understand, new guys — that’s the standard.’”

The 1990 49ers lived up to that standard, going an imposing 14-2 to earn the top seed in the NFC. But if you looked closely, cracks were starting to appear. Their running game, so lethally efficient in earlier years, had atrophied. They’d led the NFL in scoring in 1989, but were only ninth in 1990, and their margin of victory dwindled from nearly 12 points per game to barely 7. Joe Montana threw for nearly 4,000 yards and repeated his 26-touchdown pass performance of 1989, but his interceptions doubled from 8 to 16. After gaining more than 1,500 all-purpose yards on offense in 1989, Roger Craig was held to less than half that in 1990.

The 49ers and the New York Giants were the class of the NFC in 1990 — both teams started 10-0, then lost the week before their much-hyped Monday Night Football matchup, which foreshadowed the playoffs. That Monday night showdown was a defensive struggle, with the 49ers winning 7-3.

After dispatching Washington, 28-10 in the divisional round, San Francisco faced the Giants in a rematch at Candlestick Park in the NFC Championship Game. They had won seven straight playoff games (during which Montana had been peerless, throwing 21 touchdowns and just two interceptions) and 39 of their previous 44 games.

But the lack of a running game would prove decisive. The superb Giants defense, coordinated by Bill Belichick, held San Francisco to 11 carries for 39 yards. The New York defense, playing plenty of nickel and dime packages, choked the passing lanes for Montana. Save for an early third-quarter touchdown pass to John Taylor, the 49ers struggled to get untracked. Journeyman Jeff Hostetler was quarterbacking the Giants (Phil Simms had suffered a broken foot in December), and for the second time in a month, the Giants went the entire game without scoring a touchdown. But New York kept pecking away, settling for field goals that kept them in the game.

With San Francisco leading 13-9 in the third quarter, the Giants Leonard Marshall made a crushing hit on Montana, bruising his sternum, breaking his finger and knocking him out of the game. “As we both collapsed, Montana winced, and I knew it was an end of an era for them,” said Marshall. “I knew he was hurt bad and that it was likely he wouldn’t return.”

The Giants next drive stalled near midfield, when linebacker Gary Reasons — the upback and signal-caller on the punt team — called a fake and took the snap 30 yards to the 49ers 25, leading to a field goal that brought the Giants within one point, at 13-12. (The 49ers had only 10 men on the field, with starter and special teams perennial Bill Romanowski having been hurt on the previous play.)

But the 49ers were still in the lead, at home, with the ball in New York territory, when disaster struck. On a routine run into the middle, Erik Howard stripped the ball from Roger Craig, Lawrence Taylor recovered, and the Giants had the ball on their own 43 with 2:36 left. Hostetler led the Giants on a 7-play, 33-yard drive, culminating with Matt Bahr kicking his fifth field goal of the day as time ran out to send New York to the Super Bowl, and short-circuit the 49ers’ bid for immortality.

“It was a dream for us to go for a three-peat,” said the despondent Roger Craig after the game. “This is probably the lowest point ever in my career.”

“It’s by far the toughest loss I’ve ever had,” said the 49ers future Hall of Famer Ronnie Lott afterward.

“Luck runs out,” says Billick. “That was a case where the best team didn’t win. Just by the fact that Joe Montana gets hurt, and again, not to diminish a champion and say ‘it’s just luck to win a Super Bowl.’ Of course not. But that is going to be a factor and clearly that’s an example of a team whose luck ran out once they got to the playoffs.”

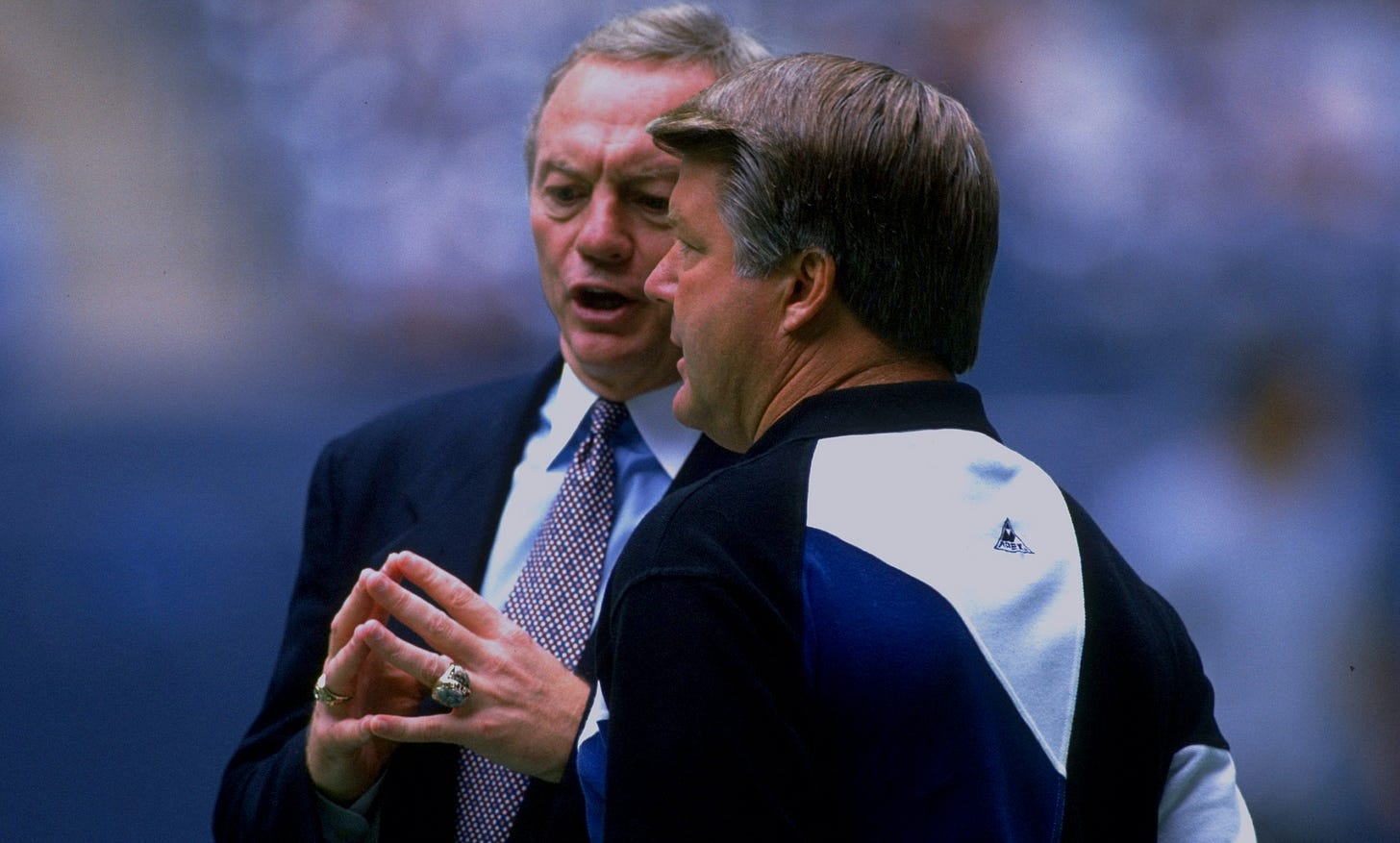

1994 DALLAS COWBOYS

Lesson: Pride goeth before the fall, and as Satchel Paige said, “Don’t look back; something might be gaining on you.”

You could argue that the Dallas Cowboys were the first of the back-to-back champions to lose their bid for a third Super Bowl at the annual league meetings. It was in Orlando in March 1994, when an overserved Jerry Jones approached Jimmy Johnson’s table — full of present and former Cowboys employees — and proposed a toast to “the Cowboys, and the people who made it possible to win two Super Bowls.” In the awkward moments that followed, Johnson, who’d been chain-drinking Heinekens, did not return the toast.

Accounts vary on what exactly happened next, though not by much. “Fuck you, have your own party,” Jones said, according to Joe Nick Patoski’s detailed The Dallas Cowboys. Johnson, in his memoir Swagger, reported that Jones said, “Fuck all of you; I’ll toast and celebrate with my friends.” Peter Golenbock, in his Cowboys Have Always Been My Heroes, reported that Jones said, “You can go back to your fucking party now.”

Later that night, Jones told the Dallas Morning News savvy football writer Rick Gosselin and the Cincinnati Inquirer’s Geoff Hobson that he was considering firing Johnson and that “There are 500 coaches who could have won the Super Bowl with our team.”

Both men were incensed and, when they met a week later, the only thing they could agree on was that the rift was irreparable, and that it was time to part ways. Rather than hiring one of Johnson’s key assistants or an experienced NFL coach or an up-and-coming coordinator, Jones seemed to take pains to prove the point that anybody could lead the Cowboys by hiring Barry Switzer, the hard-living Oklahoma coach who’d resigned in 1989 after a series of off-the-field troubles in the Sooners

It’s easy to see a parallel between the Cowboys after Johnson left and the Packers after Lombardi left. During training camp, Troy Aikman said, “Jimmy had such presence on the football field, whether it be at the practice field or the games. That is not there.”

But that’s where the similarities end. The Packers of ’68 were an aging, undermanned team that couldn’t muster a .500 record. The ’94 Cowboys were a talent-laden juggernaut, with four All-Pro players, and 11 Pro Bowlers.

One of the other challenges of trying to three-peat is that, being that good for that long in a copycat league, innovation is usually diluted. Other contenders construct their lineups specifically to beat the champions. The 1994 season was the league’s 75th, and the last without a salary cap. The 49ers had lost the previous two NFC Championship games to Dallas, and the team in 1994 was built to get the measure of the Cowboys. San Francisco signed multi-dimensional Deion Sanders from Atlanta, to offer another weapon on both sides of the ball. Ken Norton, Jr., who’d become a key element of the Cowboys’ defense and had gone to the Pro Bowl in 1993, was signed away the 49ers as well. After beating Dallas in the regular season, the 49ers finished 13-3 to the Cowboys 12-4, and that earned them home-field advantage for the 1994 NFC Championship game.

The team was on a two-year mission to snatch back what they viewed as rightfully theirs. The Cowboys had won at San Francisco in the 1992 NFC Championship Game in a loss that left Eric Davis, by then a mainstay of the 49ers’ secondary, beside himself (“I couldn’t take it. I couldn’t sleep”), and the following year, in the '93 Championship Game at Dallas, San Francisco had been overwhelmed, 38-21, by what Davis calls “the best team I’ve ever played against.”

The ’94 NFC Championship Game, played in January 1995, found the Cowboys bringing a knife to a gunfight. Dallas fell 21 points behind San Francisco in the first quarter, plagued by an interception and two fumbles. They clawed back to within 10 and were driving in the fourth quarter when, on 3rd and 10, Switzer received a 15-yard unsportsmanlike conduct penalty for bumping a referee. The rally fizzled there.

Two weeks later, in the victorious locker room after Steve Young and the 49ers overwhelmed the San Diego Chargers, 49-26, in Super Bowl XXIX, the 49ers’ president Carmen Policy pointed to Ken Norton, Jr., and said, “I’d like to think getting him put a small dent in Dallas’s armor.”

Conventional wisdom holds that the move from Johnson to Switzer further upset the Cowboys’ chemistry, allowing San Francisco to gain an edge, but Davis disagrees.

“You could have gotten Lombardi, Paul Brown, we can throw in Bill Walsh and Don Shula, all of them coming on that coaching staff,” Davis says. “We were going to beat them that year because we had to. Everything that we did, every person that came to our team, every practice, every moment was about beating them.”

(In a footnote, Switzer would win the Super Bowl the following year — perhaps proving Jones’ point — after the Cowboys signed Deion Sanders away from San Francisco to a one-year, $12 million contract.)

1999 DENVER BRONCOS

Lesson: Don’t have your legendary quarterback retire.

The Broncos had lost three Super Bowls and the AFC had lost 13 straight when Denver upset the Green Bay Packers in Super Bowl XXXII to win their first Lombardi Trophy. A year later, they enjoyed a bit of good fortune when the high-powered Vikings lost at home to Atlanta in the NFC Championship Game. The “Dirty Bird” Falcons were good, but didn’t pose nearly the threat to Denver’s defense as Randall Cunningham and Randy Moss would have. But after their second straight Super Bowl win, John Elway announced his retirement.

And the following season, the Broncos were mortal, becoming a textbook case of how important a quarterback can be.

“You and I could have won with Elway,” says Ernie Accorsi, whose Browns lost three heartbreaking AFC Championship Games to an earlier incarnation of the Elway-led Broncos. “I mean, he was just that good. He wasn’t a programmed quarterback who was coached perfectly. He was just one of those guys — when you pick sides on the sandlot, he’s going to win the game just on pure talent. So they had no chance for that without him. They lost their best player.”

As it turned out, they lost their two best players. After Mike Shanahan named the young Brian Griese starter over veteran Bubby Brister, the Broncos got off to an 0-3 start. Late in the first quarter of the team’s fourth game, against the New York Jets, Griese threw an interception to Jets’ safety Victor Green. Denver running back Terrell Davis tackled Green at the end of the play and, in so doing, tore both his anterior cruciate ligament and medial collateral ligament. Davis had run for 5,296 yards and scored 53 touchdowns the previous three seasons. He’d be out for the year, would play parts of only two more seasons, and was never be the same. After that 0-4 start, the Broncos split their last 12 games, winding up 6-10, and were never a factor.

NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS 2005

Lesson: Just because the coach and quarterback is the same doesn’t mean the team is the same.

It was one week after their second straight Super Bowl win — New England’s third in four years — at the Pro Bowl in Hawaii. Player introductions came by team, and the champion Patriots were last. As the Patriots’ players stood in a circle in the locker room, waiting to be introduced, Tom Brady looked each of his teammates in the eye and said, “You know what? No one’s ever won three in a row.”

Tedy Bruschi was in the circle, making his first Pro Bowl appearance. He was wearing the same cleats he’d worn a week earlier winning the Super Bowl. “That’s Tom, of course, but when you’ve got guys like that, that gets floated out there immediately,” says Bruschi. “And a part of me thought, ‘Dude, can we just relax for a second? I mean, I’ve still got confetti on the bottom of my shoes, man.’”

The Patriots’ three-peat quest would soon take a series of strange turns, beginning a day and a half later when Bruschi, back home in Massachusetts, suffered a stroke. That was part of a spate of losses, on the field and in the coaching staff. Both defensive coordinator Romeo Crennel and offensive coordinator Charlie Weis left for head coaching jobs, cornerback Ty Law was released, and linebacker Ted Johnson, still suffering the effects of multiple concussions, retired.

New England had an up-and-down 2005 regular season, alternating wins and losses through the first nine weeks of the season. Bruschi, somewhat miraculously, came back to play in Week Seven, and helped shore up the defense (he shared Comeback Player of the Year honors with Steve Smith), as New England wound up 10-6 to edge the Dolphins in the AFC East.

But something was missing — that sense that the Patriots were better than everyone else, and that everyone else knew it as well. “We were fractured,” Bruschi says. “We were just a different team. Everyone could feel it. There was, you still have that feeling — guys like myself and Brady and the guys that had won so much. You know what to do. But you also know when it’s not the same.” The Patriots defense, first and second in points allowed during their Super Bowl seasons of ’03 and ’04, dropped to 17th in points allowed in 2005.

The wild-card week win over the Jaguars, 28-3, was routine, and the two-time champions came to Denver in the divisional round still confident that they could win it all again. And why not? The Patriots had won 10 straight postseason games and three Super Bowls already. Tom Brady had never lost a postseason game, and they would be facing the Denver Broncos, still trying to find their way five years after Elway’s retirement.

In their record run of 10 consecutive postseason victories, the Patriots had turned the ball over six times (compared to 27 takeaways). But on the chilly January day in Denver, New England played like an inexperienced, undisciplined team, giving up the ball five times, twice in the last two minutes of the first half.

In the second half, there was a fumbled punt return, but the back-breaker came late in the third quarter, the game still in doubt, Denver leading 10-6, when the Patriots were driving. Brady’s pass into the end zone was picked off by Champ Bailey, who returned it 99 yards, before being knocked out of bounds at the New England 1 by Benjamin Watson. The interception symbolized a larger truth. The Patriots in previous years had the heart of a champion, and Watson — coming from the other side of the field and tracking down Bailey after his full-length sprint — hit Bailey right before the pylon and knocked the ball loose. In one of those charmed years for the Patriots, the ball might have been judged to have gone out of the end zone, signaling a touchback and New England’s ball at the 20. But this was the year luck ran out, so the officials ruled that the ball went out of bounds at the 1. Denver scored on the next play, a 14-point swing that gave them a two-score lead they’d never relinquish.

In the thin air of Denver, Bruschi felt it all slipping away: “With the turnovers, the pass interference and all of that stuff, a couple of arguments on the sidelines and it’s like, ‘Okay, there we go. That’s it.”

Read Part III right here.

Michael MacCambridge (@maccambridge) is the author of “America’s Game: The Epic Story of How Pro Football Captured A Nation” and other books. Ana Sofia Meyer and Emmanuel Ramirez provided research assistance for this article.

ICYMI, our 2024 NFL Season Preview features at Go Long: