INTO THIN AIR, Part I: Why It’s (Nearly) Impossible to Win Three Straight Super Bowls

Michael MacCambridge, one of the nation's greatest football writers, authors this three-part series on the treacherous pursuit of three straight Super Bowl titles. Can the Chiefs pull it off in 2024?

Editor’s note: We welcome one of the nation’s best pro football writers for this three-part series. Michael MacCambridge chats at length with several of the greatest players, coaches and execs ever to see why it’s so unbelievably difficult to win three Super Bowls in a row.

Patrick Mahomes and the Kansas City Chiefs will give it their best shot in 2024… but it’s a mountain to climb.

Enjoy.

By Michael MacCambridge

I | THE CHALLENGE

Forty-three years after hanging up his helmet for the final time, Joe Greene still moves with a quiet authority. He is no longer the fully chiseled 6-foot-4 and 275 pounds of muscle — some contents may settle during shipping — but he continues to exude a formidable presence. You can sense him entering a room. To see his stately gait and his weathered hands, one can easily envision the country-strong force of nature that he was during the heyday of one of pro football’s great dynasties.

For much of the 1970s, Greene and the Pittsburgh Steelers were the standard, the empire, the dream-killers. The Steelers’ dominance directly altered the franchise histories of the Baltimore Colts and Oakland Raiders, the Dallas Cowboys and the Houston Oilers. Contenders would enter Steeler showdowns full of swagger and attitude, and leave thoroughly defeated. The Raiders’ John Madden, after the 1974 AFC Championship Game, could only say of Greene and the Steelers, “They beat our butts.”

The Steelers won four Super Bowls in six seasons — back-to-back titles in 1974 and 1975, and again in 1978 and 1979, the only team ever to do it twice. Greene looks back on those days with a justifiable measure of pride. But now the subject at hand — the one challenge that eluded the Steelers and every other team that encountered it — sends him into regretful lament.

Sitting in his trophy room in a gated community in north suburban Texas, the heart and soul of the “Steel Curtain” defense grows contemplative as he ponders the physical, emotional and psychological toll of trying to win three straight Super Bowls. He vividly recalls a moment from nearly half a century ago that sticks with him as much as any of his triumphs. And as he begins to address the subject, Greene sighs—and for an instant he looks every bit of his 77 years.

“I missed the tackle in the fourth quarter on the stunt,” he says softly. “I came around to hit Ken Stabler, and if I'd have made that tackle the game was over. Stabler ducked and completed a pass for a first down.”

Left unsaid was what followed. It was a single play in the first game of the 1976 season, but it was part of a team-wide breakdown that saw the Steelers squander a 14-point fourth-quarter lead to the Raiders, piercing their aura of invincibility in the process. Three and a half months later, Pittsburgh’s quest to win three straight Super Bowls would end on the same field. Greene remembers the glory of the four Super Bowl wins and the long road to each, but decades later, he’s still rankled by the one that got away.

A fact that you have heard often, and will hear more frequently in the coming weeks and months: The Kansas City Chiefs this season will endeavor to become the first team to win three straight Super Bowls. It’s not merely that the elusive three-peat hasn’t been done before; no one’s come close, leading some to believe that it’s virtually undoable, now more so than ever. In the 58 years of the Super Bowl era, eight teams prior to the Chiefs won back-to-back Super Bowls. None of them got back to the Super Bowl the next season; only three got as far as the conference championship game.

Beyond the immediate challenge, the Chiefs’ quest sheds light on a profound if rarely-discussed fact: It’s objectively more difficult to build a dynasty in the NFL than any other major professional sports league. And it always has been.

Since the Super Bowl era began in the 1966 season, every other major American sport has witnessed multiple three-peats — teams winning a league title for three years running or more. The NBA in the ’60s saw the conclusion of the Boston Celtics dominant run of eight straight titles, and later witnessed back-to-back-to-back championships twice from the Michael Jordan-led Chicago Bulls (’91-’93, ’96-’98) and once from the Los Angeles Lakers in the post-Jordan aftermath (2000-2002). Major League Baseball has seen a pair of three-peats: the Oakland A’s from 1972-’75 and the New York Yankees from 1998-2000. The NHL has seen two different teams run off a string of four consecutive titles — the Montreal Canadiens (’76-’79) and the New York Islanders (’80-’83).

But since the inception of the Super Bowl at the end of the 1966 season, it has yet to happen in the NFL.

Why is it so much harder to win three straight in the NFL? What happened to the eight predecessors of the Chiefs in the Super Bowl era? Can any lessons be learned from the experiences of those teams that might provide insight into Kansas City’s epic quest in the season ahead? A summer spent talking with former players, coaches and administrators cast some light on those questions, and underscores one incontrovertible truth: The NFL is constructed to avoid long runs by one dominant team. The same elements that offer hope to every one of the league’s 32 fan bases — the draft, free agency, the salary cap and salary floor, the scheduling system and playoff structure — encourage competitive balance and make it difficult to dominate for long stretches. The National Football League is an anti-dynasty machine.

And yet here we are.

Go Long is your home for longform journalism in pro football.

We are completely powered by you.

Subscribers can access the rest of Part I below and Michael MacCambridge’s three-part, 13,800-word series in its entirety.

The Chiefs have won two straight Super Bowls, have won three of the past five Super Bowls and played in four of them, have gone to six straight AFC Championship Games and won eight consecutive AFC West titles. This has been accomplished in an age of unprecedented competitive balance, as Joel Bussert — for decades the league’s vice-president of player personnel and liaison to the Competition Committee, as well as the NFL’s de facto in-house historian — points out.

“It was never easy,” says Bussert. “There were only two instances of winning three titles in a row before the Super Bowl era. It's harder than ever to win two in a row. Before the Chiefs, there hadn’t been a repeat champion in 19 years. This was the longest stretch of no repeat champions in the history of the league.”

The first team in the NFL to win three straight titles was the Green Bay Packers from 1929-31. This was the early Dark Ages of the league, with 12 teams in ’29 shrinking to 11 in ’30 and 10 in ’31. There were no divisions and no championship game then, and the league title was determined by winning percentage, since teams played a varying number of league games. Even then, the league’s archaic rules treated games ending in a tie as though they had never been played. It wasn’t until 1972 that the NFL finally began computing a tie as a half-win and a half-loss. If the league had done so in 1930, the Giants (13-4) would have edged the Packers (10-3-1) in winning percentage.

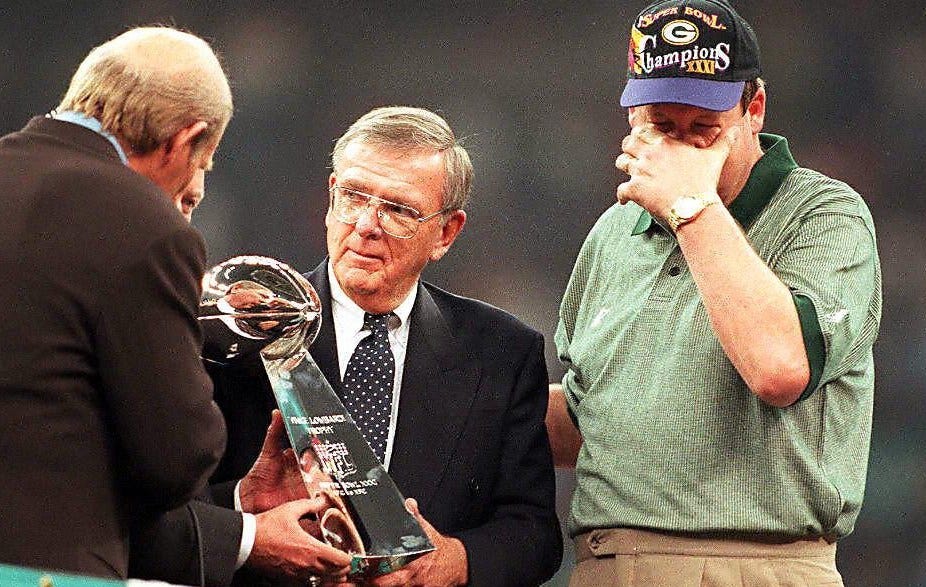

The only other team in NFL history to win three straight titles was Vince Lombardi’s Packers in 1965-67, the first coming during the last season before the merger agreement between the NFL and AFL, the last two years coinciding with the dawn of the Super Bowl era. The Packers played just two postseason games in ’65 and ’66. It wasn’t until 1967 in the NFL and 1969 in the AFL that a team needed to win three postseason games to win the Super Bowl. In 1978, with the addition of a second wild-card team in each conference, some teams had to win four postseason games to win the Super Bowl. Now, with 14 teams in the playoff field and only one bye in each conference, 12 of the 14 entrants must win four straight games in the postseason to raise the Lombardi Trophy, as the Chiefs did last season.

“As leagues get bigger, it gets harder to string together championships, for one thing,” says Bussert. “And with these longer postseasons, that also makes it harder to string together championships.”

Those are only some of the myriad factors in the NFL working against long title runs in general, and three-peats in particular. Among the others:

Free Agency. The biggest obstacle to repeat titles is the one that’s been reshaping pro football for 30 years — the advent of free agency, along with the salary cap and salary floor— which was signed into the 1993 collective bargaining agreement and went into full effect in 1995. There had been six repeat champions in the first 29 years of the Super Bowl era before the advent of free agency and the cap, but only three since then.

“With free agency, in four years your guys are free to roam,” says Ron Wolf, the Hall of Fame general manager who brought the Green Bay Packers back to glory in the ’90s after decades working in personnel with the Oakland Raiders and Tampa Bay Buccaneers. “In my early years that never happened in pro football. You were able to keep your guys forever and that way you could build and plan, and you knew who was what, where, when and how. Then suddenly here comes free agency and now you have to determine the guys that you're going to lose. You’re going to lose guys, there’s no question about that. Hopefully you’re picking the right people to take the place of a player who is a bonafide starter and in some cases a Pro Bowl player that you can no longer afford because of the cap. And to me, that’s what separates everything — it is your ability to maintain that level.”

Player movement has made it harder to repeat in every sport — only one three-peat in Major League Baseball since free agency, and none in the NHL. The three-peats in the NBA have more to do with smaller rosters and the way one or two transcendent players — Michael Jordan and Scottie Pippen; Shaquille O’Neal and Kobe Bryant — can build a dynasty. (Fittingly, the portmanteau “three-peat” is trademarked by Pat Riley, a legendary coach in the sport where the accomplishment is most common.)

• The Salary Cap and Salary Floor. When people discuss free agency and the salary cap, they too often forget the salary floor. Since those payroll parameters were implemented in the NFL in 1995, every team in the league possessing the same approximate resources to spend on player salaries has further fostered an environment of competitive balance. (In the NFL, teams must spend at least 89 percent of the cap over a four-year period, while the league as a whole must spend 95 percent of the cap over the same period.)

By comparison, Major League Baseball has a caste system in which payrolls range wildly — in 2024, the span is from $312 million to $63 million. That means teams like the Mets and Yankees play dozens of games this season against teams with less than half their payroll. There are no such Bingo free spaces in the NFL, where at time of writing, this year’s total payroll allocations ranged from $301 million to $249 million.

• So many moving parts. With roster sizes twice as large as any other major American sport, there is a complexity to the chemistry of football teams that defies easy understanding, and is further destabilized by free agency and the cap.

Few would argue that quarterback is the most demanding and important position in team sports, but even a brilliant quarterback can do only so much. Compare that to basketball, where a single ascendant player — Bill Russell, a Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, a Steph Curry — can turn a perpetual doormat into a perennial contender. When Abdul-Jabbar, then Lew Alcindor, was drafted by the Milwaukee Bucks in 1969, the second-year expansion team was coming off a 27-55 record. With the rookie dominating from the first tip-off, Milwaukee became an instant contender, winning 56 games his rookie season and the NBA title the next.

Those kind of turnarounds are rare in the NFL, and the fragile chemistry of a team can be influenced by any number of subtler elements. In the 1996 season, the Packers won their first Super Bowl in 29 years, and were poised for a repeat a year later when they were heavily favored but lost in an upset to John Elway and the Denver Broncos. Ron Wolf still stews over this, and the pregame noise and speculation about whether coach Mike Holmgren would stay or leave.

“We had a little distraction then because there was all this talk about Holmgren going to Seattle,” says Wolf. “But the bottom line is we lost the game and I blame that more on free agency. We had guys that were worried about their contract for the next year that weren’t mature enough to understand where they were at that particular moment. Plus, we made a bad personnel decision in letting a player like Sean Jones go. If we had kept him, we would’ve had better player discipline within the locker room. He wouldn’t have allowed guys to sit over there on their helmets and worry about next year. It’s about this year.”

• Brain Drain. Super Bowl champions — especially repeat Super Bowl champions — routinely lose essential members of the coaching staff. Both the Packers in 1968 and the Cowboys in 1994 lost their head coaches, and the Dolphins in 1974 and the Patriots in 2005 lost both their offensive and defensive coordinators.

“You win a Super Bowl, your coaching staff is gone,” says Tedy Bruschi, who saw the exodus out of New England after the Patriots’ second straight title in 2004. “It is just hard to keep everyone together, and when you lose a coach, that’s a big change, especially if it’s a coordinator. So that’s just another way when you win, the league it makes it harder for you to do that again. The players want more money, the coaches end up leaving, you draft last and then you lose free agents. It’s a firestorm in terms of what happens, with all the elements that are tearing your team apart.”

• Desire. Perhaps in no other sport is career success so inextricably tied to the winning of a ring. All that is sacrificed — not only physically but emotionally — to win just one makes it daunting to go back to the well repeatedly. Once you’ve finally reached the mountaintop, are you willing to make all those sacrifices again?

“The one part of it that you’re never going to be able to solve, and no one is going to be able to solve except God, is what’s inside the heart of athletes,” says Ernie Accorsi, the longtime general manager of the Colts, Browns and Giants. “You cannot generalize a 53-man roster. They’re not all going to be thinking the same, feeling the same. I mean, sure, they’ll say, ‘I want to be on the first team that wins three in a row.’ It’s not exactly the same.”

• The media. Brian Billick, who coached the Ravens to a win Super Bowl XXXV, also notes the way the pressure ratchets up at the very moment the ultimate goal has been achieved. “First question you get asked, five minutes after you win the Super Bowl,” says Billick, “is, ‘Can you do it again?’ Um, can I have an hour to enjoy this one?”

It is fair to say that as the money and media coverage has grown, there is more scrutiny and more distractions than ever before. Ray Nitschke’s DMs weren’t being inundated with thirst traps on the eve of a big road game. No one gave Bob Griese grief because he wasn’t throwing enough touchdown passes for their fantasy team. The amount of money, distractions and scrutiny players encounter today transcends anything from the Twentieth Century, especially for championship teams.

“Is it harder to keep a team focused as a team in today’s age? Absolutely,” says Billick. “To be able to fend off the outside influences on your team, notwithstanding the cap and the fact your team changes. There’s no question that those distractions and the players’ preoccupation, and that inward-looking mentality, certainly makes it harder to hold onto that team, that Band of Brothers mentality, than it was before.”

• The Schedule. One of the subtler factors that makes repeating more difficult is the unique structure of the NFL’s “position scheduling.” In other sports, with minor rotational variances, schedules are balanced, and thus broadly similar among teams within a division and conference. But for nearly 50 years, the NFL has used a slotted “position” scheduling system to help encourage competitive balance, meaning the best teams are rewarded with tougher schedules the following season. (For the record, when it was conceived by longtime Pete Rozelle aide Jim Kensil, the main impetus for the change — during the league’s move from a 14-game regular season schedule to a 16-game regular season schedule in 1978 — was to increase the number of attractive marquee matchups for television.)

When the league expanded to 32 teams in 2002, it adopted what was known as the 6-4-4-2 method: teams played six games (home and away) with the other three teams in their division, four games against a rotation of the other three divisions within the conference and four games against a rotation of the four divisions in the other conference. Finally, each team had two “positional” games: first-place teams from the previous season played the two other first-place teams in the conference that weren’t already on the schedule; second-place teams played other second-place teams, etc.

When the NFL made the cash-grab move to a 17-game regular season in 2020, it added yet another “positional” game in the schedule, against another similarly-placed team from the other conference. That means any team that finishes first one year has to play five other first-place teams the next season. That discrepancy in schedule strength is one reason for the consistent turnover in division champions — at least four of eight division champions have been new every year this decade.

• The Playoffs. In a league where the margins between victory and defeat are so fine, the compressed nature of the NFL playoffs in the single-game elimination tournament format leads to a kind of insistent pressure that’s different from other major sports.

“In a best-of-seven series, usually the best team is going to win,” says Billick. “But football is different. It’s not the best team — it’s the best team for those sixty minutes.”

Up until 1978, when only eight of the 28 teams made the playoffs, the postseason was a straightforward three-game tournament. But in 1978, the NFL added a second wild-card team to raise the playoff field to 10 teams. It rose to 12 teams in 1990, and then to 14 teams in 2021. More playoff teams meant fewer byes for divisions champions, more playoff games, a longer road to the Lombardi Trophy, and more chances for one bad bounce to change the fortune of superior teams.

“The one-game knockout versus four out of seven is important,” agrees Hall of Fame coach Tony Dungy. “I remember Allen Iverson and Philadelphia going off against the Lakers (in the 2001 NBA Finals), and they win Game 1 out in Los Angeles. Then they lost four straight. If that was football, and it’s just one game, Los Angeles is out.”

•Mojo. Finally, there’s one other element that gets mentioned frequently. But it’s more nuanced than language will necessarily allow, and when coaches or GMs try to articulate it, they spend as much time explaining what they don’t mean as what they do.

“To be a Super Bowl champ, a number of things have to come into alignment,” says Billick. “I’m not saying you just luck into it. Certainly the best team is usually going to win because you have to go through the gauntlet of the playoffs and the Super Bowl. But to be a Super Bowl champ, there are so many things that have to align during the season — health, what injuries you get and when you get them, the schedule itself. There’s a lot of factors that have to kind of go your way to win it. So the idea of that happening two years in a row — let alone three years in a row — is almost prohibitive.”

Read Part II here.

Michael MacCambridge (@maccambridge) is the author of “America’s Game: The Epic Story of How Pro Football Captured A Nation” and other books. Ana Sofia Meyer and Emmanuel Ramirez provided research assistance for this article.

ICYMI, our 2024 NFL Season Preview features at Go Long:

"The Steelers’ dominance directly altered the franchise histories of the Baltimore Colts and Oakland Raiders, the Dallas Cowboys and the Houston Oilers."

From this sentence alone near the top I knew this would be good. That alone would be a story I'd enjoy seeing explored. Enjoyable read, and very McGinn-esque with the thoroughness. No wonder they're two of the best.

You can downplay the Packers 1929-31 three-peat if you want, but downplaying the 65-67 titles and saying only the last 2 count is disingenuous. There is no way the 65 team loses the an AFL team. The 66 and 67 teams destroyed the AFL teams in what are now called Super Bowls. The 65 team was basically the same team but younger.