Anthony Gould is your old-school alternative

The wide receiver wanted to leave Oregon State in the dust. Instead, he sucked it up and started leaving cornerbacks in the dust. We chat with the 5-foot-8 speed demon.

Hell no, he wasn’t happy. He was fed up with being ignored. Two years into college, barely contributing more than the water boy on Saturdays, he was fully prepared to leave Oregon State behind.

Anthony Gould can still feel that urge to bail. It was strong.

Through the 2019 and 2020 seasons, the wide receiver caught exactly zero passes while playing a whopping 10 to 15’ish snaps. If by some miracle he was inserted into the game, Gould blocked. Naturally, social contagion kicked in. He wanted to transfer to a school that’d give him a chance to shine and, honestly, it’s hard to blame any young athlete seeking a better opportunity. This is right when the transfer portal started giving college athletes the ability to become free agents on-demand.

No longer did anyone need to feel stuck. Greener pastures were available.

Gould informed his mother he was ready to transfer and Stacy Johnson told her son he was more than welcome to change schools. He was old enough to make his own decisions.

But in her next breath, Mom supplied the sort of feedback that’s becoming increasingly rare.

“You’ve never been a quitter,” she said, “so why be one now?”

Those final four words cut like a knife. That’s all she needed to say.

Go Long is your home for independent longform in pro football:

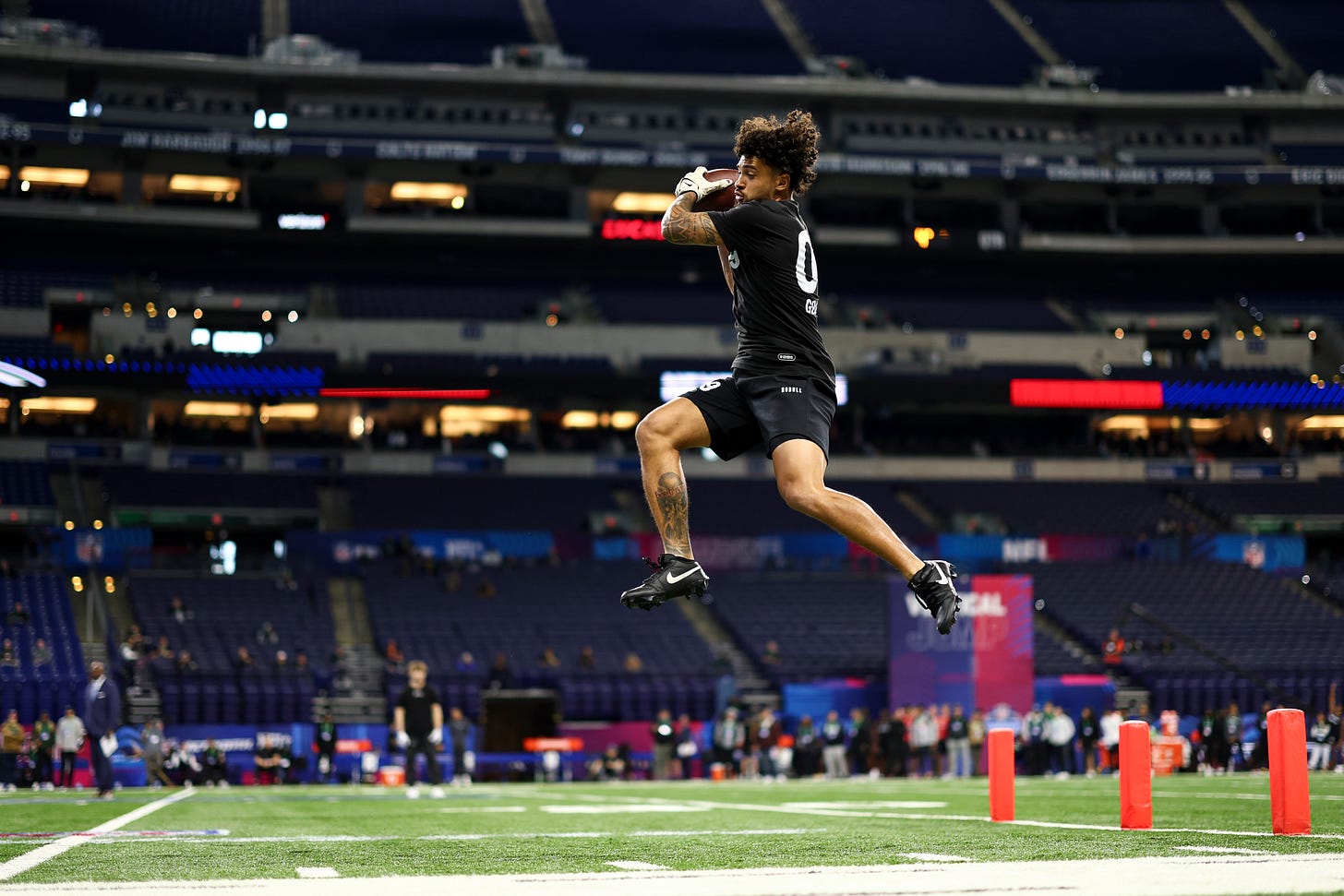

The way Gould was raised by Mom? Back in Leavenworth, Kansas? Abandoning Oregon State would’ve been akin to abandoning the man he was trying to become. Gould played the next three seasons for the Beavers, catching 44 balls for 718 yards during the 2023 season and — now — is NFL-bound. The 5-foot-8, 178-pounder is one of the fastest receivers in the draft, a former high school track star who ran a 4.39 in the 40 and accounted for three 50+ yard pass plays last season. There’s a role for Gould in the pros as a returner and vertical weapon.

At a talent-rich position, he offers something different on and off the field.

This fight-or-flight moment in Corvallis, Oregon was the turning point in his life.

“It’s definitely a trait to be able to bounce back,” Gould explains. “And unfortunately, a lot of people don’t have that trait. They don’t know how to deal with adversity. So that’s something that’s been instilled in me since I was little, and I’m thankful for that.”

Tales of restraint are becoming borderline-obsolete with enablers and yes men and boosters infiltrated into college football like never before. It’s human instinct for any player riding the bench to seek playing time elsewhere, and one leading voice (Chase Griffin) explained to us why Name, Image and Likeness (NIL) has transformed college athletics for good.

The farce is over. College athletes have deserved compensation for ages. A free diploma doesn’t come remotely close to covering their impact on campus. And if coaches can change school to school, why not the players? Further, the ability to make money is getting players to their senior year of college. Only 58 underclassmen have declared for this year’s draft, the lowest since 2011. From ‘16 and ‘22, an average of 115 players left for the draft early. Five of the top seven quarterback prospects transferred at some point and empowerment is good for the sport. We should celebrate the collegiate arc of Jayden Daniels, from Arizona State anonymity to Heisman Trophy-winner at LSU. We should trumpet the turnarounds of Bo Nix (Oregon) and Michael Penix Jr. (Washington). Both transferred and fully maximized their second chances by transforming into potential first-round picks.

If a quarterback can walk into a completely new building and win over teammates, that’s damn impressive. That’s what’s required in the NFL.

Beneath these headlines, however, are hordes of prospects you’ve never heard of who changed schools simply because they were unhappy. And disappeared. The prospect who fought through turmoil on campus — decided to stay put — and got to the other side is harder to find. There’s immense value to this character, this too-damn-bad-KEEP-DIGGING ethos. Because when the NFL inevitably wallops you across the face with a 2x4, there is no portal. No fantasy-land alternative. You’ll simply be released. Replaced. Forgotten. Figuring out which prospects are hardened to handle this harsh, yet refreshing meritocracy is no easy task for scouts.

Gould remembers feeling a magnetic pull to other schools. Change was enticing.

But he’s old school. He sucked it up.

Buried on Oregon State’s depth chart, he convinced himself that all he needed was one opportunity.

“And once I get that opportunity, run with it,” Gould says. “So I’d always tell myself: ‘Leave no doubt.’ Every time I’m on the field, leave no doubt: Any role, any capacity, he has to be on the grass. That’s what I tell myself every day. That’s how everything’s structured in my life: ‘Leave no doubt.’ Whether that’s relationships, working out, meeting new people, business, just being able to leave no doubt. Let people know, ‘I’m here,’ when it comes to being on the field. You’re going to have to feel me.

“I’m leaving no doubt that you have to put me on the grass at some point. However you guys do it, you have to figure it out. But you’re going to have to play me. So that’s the mindset I go in with every day of practice.”

That’s also a mindset honed by a mother who served as a master sergeant in the Army for 20 years. Johnson worked at the military prison right in Leavenworth while also deploying to Iraq and Cuba when Gould was between the ages of 6 and 8. After this, she worked for the SHARP Academy, a group within the Army that spreads education on sexual harassment, assault and rape prevention. Under this roof, hard lessons were learned. Gould’s older sister (Mahogani Gant) loves to tell her little bro that she absorbed the brunt of Mom’s punishment, and that Mom actually softened up over time.

Still, Gould can picture “that look,” that piercing glare whenever Mom threatened him with the dreaded wooden spoon.

“That was my thing. The wooden spoon would have my name on it,” Gould says. “So that’s when I knew I needed to start acting right. It was tough at times. But growing up, a single mom in the Army, she’s taking care of two kids. I wouldn’t want to change it. I know it was all out of tough love. I love my Mama to death, and I know she did everything she could to get to where I am.”

Oh, he took a few licks. The spoon was not a prop. But it got to the point where the sound of Mom pulling the drawer open for the spoon was all it took to snap Gould into shape.

Whenever his mother headed to Washington D.C. or other random cities for SHARP, Gould stayed with friends for one or two months at a time. As far as military life goes, this was relatively stable. Beyond Gould’s fourth-grade year, Johnson didn’t need to travel overseas.

Granted, he heard so many chilling stories.

If anyone commits a crime in the military, they’re sent to Leavenworth. There’s a good chance you’ve heard the town’s name referenced in movies. Mom’s craziest stories involved prisoner transport. Johnson helped bring suspected terrorists to the Guantanamo Bay detention camp. Once, she needed to transport a terrorist who tried sneaking a bomb onto a plane inside his shoe. Johnson assisted in bringing this person from San Diego to Gitmo. Gould notes that his mother started helping out at Guantanamo Bay itself after the allegations of torture. Gitmo was a difficult place to put into words. Several times, inmates would go on strike and refuse to eat or drink water. Officers needed to force-feed them.

Add Gould: “Some of the stuff she’s told me, it’s just like… ‘Wow.’”

Perspective stuck. Gould spoke often to people in special forces who’ve been in combat.

On to high school, he believes this upbringing gave him an edge over peers.

“Definitely a blue-collar mindset,” Gould says. “It’s not easy growing up like that. You definitely get a tough love and a sense of discipline. My Mom, even to this day, she’s very structured. She likes things organized in order. Her way. So having that instilled in me at a young age has definitely helped me learn the importance of discipline and hard work.”

His final two years of high school, Gould relocated to Salem, Ore., and lived with his aunt. He excelled in both track and football, totaling 1,009 yards receiving and 612 yards rushing with 22 touchdowns as a senior.

Gould’s only scholarship offer came from Oregon State, a school with one Pac-12 victory the prior two seasons. His Mom relocated to Vancouver, Wash., 91 miles away, for a similar job — she’d be able to witness every catch, every touchdown.

Then… he hardly played. His football career was coming to a screeching halt. Gould was open to transferring anywhere in the country, from the west coast to back home in Kansas to the east coast. Didn’t matter.

His mother spoke up.

One of his closest friends on the team spoke up.

Gould chose to ride it out at Oregon State.

The more he talked to people in the building, the more Gould realized the grass isn’t necessarily greener. Resetting elsewhere would mean adapting to a new playbook, new teammates, new everything with zero guarantees. In Year 3, Gould vowed to play “loose” and “free” and stop trying to be so perfect every play. A mental switch that changed the total trajectory of his career.

He took the standard set by current Giants wideout Isaiah Hodgins to heart, and passed it along to younger receivers by training with purpose. Changing his nutrition. Speaking up more day to day to day.

“That’s kind of how I ended up really taking over that next leap,” Gould says.

He gave coaches no choice but to use him offensively. In the second game of the 2021 season — a 45-27 win over Hawaii — Gould caught seven passes for 119 yards with a touchdown. He may be shorter than your local CVS pharmacist, but he can jump. On his first TD as a Beaver, Gould shook a DB at the top of his route, broke inside and put his 39 ½-inch vert to use by fully extending to pluck a high ball in the end zone.

Gould flexed both biceps and crossed his arms for the cameras.

This game completely refueled any confidence he lost those first two years.

“That was the point where it was like, ‘I’m here. I can do this. I can do this at a high level and the only person that could stop me is me,” Gould says. “So that was kind of the moment where everything in my mind shifted towards, ‘I’m a guy on a national stage. I’m one of the top guys in the country.’ After that, I just maintained: This is the standard. We have to be above the standard every day. … That was definitely probably the turning point in my career.”

Over his three seasons, he gradually improved.

Speed is his game. Speed, speed and more speed.

There’s Gould catching a bubble screen at his own 25-yard line, eluding one defender and slamming the accelerator en route to the end zone vs. San Diego State. There’s Gould getting a step on a corner from Cal with an Iverson-quick crossover inside before then breaking back outside to gain separation and gracefully haul in a diving corner shot over his shoulder on third and 8. There’s Gould turning Arizona cornerback Ephesians Prysock into a pretzel. He burnt this poor sap so badly on third and 16 that his own quarterback didn’t have the arm strength to lead him for a touchdown on a 52-yard reception. The Beavers settled for a field goal and lost, 27-24. His third 50+ yarder last fall also came on third and long. This one featured two head fakes.

Gould has always felt “naturally fast.” In his mind, he’s always been a football player who ran track on the side. Not the other way around.

“I like to say I can move in all four ways. I can move side to side, front to back,” Gould says. “There’s a lot of guys who are fast in shorts and a t-shirt, but put some pads on and it’s a different story. And that’s where I think I really excel. I put the pads on and I feel like I get even faster. I’m good in knee pads, thigh pads, shoulder pads, and a helmet. I’m moving, too. That’s one of my favorite parts of my game — how easily I can accelerate and get the top speed with full pads on.”

All while getting funky with his route running. Echoing many receivers before him, Gould points to former Buffalo Bills wide receiver Stevie Johnson as a true innovator of the position, as someone “ahead of his time.” His 7-on-7 coach was from the same area as Johnson, Oakland, Calif., and told Gould to study this route running. It wasn’t normal. Nobody was getting to spots on the field with this level of creativity. Johnson effectively turned the wide receiver position into a game of pickup basketball, which he explained at length two years ago.

Gould also studies Doug Baldwin, Jaylen Waddle and Tyreek Hill but usually finds himself coming back to Johnson, a receiver who did not obey a rigid route tree.

Adds Gould: “If he was playing now, it would’ve been a whole different story.”

The key is timing. Leaving the DB in his dust — ASAP — and getting to a spot exactly when the quarterback expects you to be there. He views the position as a form of art.

“You’re going to have to move and manipulate your body,” Gould says. “I might have to put a little sauce on it to make him think I’m going outside-release while I’m really wanting to run a slant. Some people dance, some people sing, some people paint. We like to get open.”

The foundation of his artwork is that speed. Gould tries to play off of a defensive back’s fears. Film study is a major part of it. If he’s facing a lanky cornerback, he tries to rev up that corner’s internal clock to the point of discomfort. Fear. He wants to get that corner playing on his (literal) heels. Against small corners, going deeper is more difficult. That’s when he brings an element of craftiness. That’s when he’ll synchronize a juke with a head fake within a route that’s impossible to define on the chalkboard.

Size is a concern for teams. Gould does not bring the catch radius of other wideouts in this class. His hands are small at 8 7/8 inches. He also only forced three missed tackles through his career. This remains a big man’s game. Whether Gould can bust out that paintbrush and shake free from corners in the pros is unknown. The good news is that he was no undersized Swiss army knife at Oregon State. Gould operated predominantly as an outside receiver.

His numbers are a bit misleading, too. Pull up a game and you’ll likely see the team’s quarterback missing him deep.

Gould could’ve transferred into a new offense at any point.

Instead, he stayed true to himself and believes an NFL team is getting more than what’s on film.

“I’ve been waiting for this my whole life,” Gould says. “Now, we’re here. Now, it’s time to go capitalize. So whatever team gets me, you are going to get a dog. You’re going to get someone ready to compete and ready to go from Day 1.”

At the time of our conversation, Gould had one top-30 visit planned with the Kansas City Chiefs. Catching passes from Patrick Mahomes is of course a dream scenario for all wide receiver prospects. This would bring him back home, too. Leavenworth is a short 34-mile drive to KC.

His mother has since moved back to Kansas City.

She won’t need to pull the drawer for that wooden spoon anymore.

“That’s my biggest supporter out there,” Gould says. “Right, wrong or indifferent, she always going to have my back.

“Looking back on it. I’m glad that I stayed at Oregon State.”

Bob McGinn’s nine-part, 40th annual draft series begins Wednesday AM. Our Hall of Fame sports writer has spent months speaking to scouts across the NFL to bring you the good, bad and ugly. The series is exclusive to our paid subscribers.

ICYMI: