Why we should all put Ronde Barber's name right there with Charles Woodson (he explains)

The Buccaneers great is a Hall of Fame finalist this year. He looks back at his storied career, from the torn PCL to the pick-six in Philly to what made his game so special.

Sometimes, a truly great player simply gets lost in time.

Names blend with other names and we forget how special that player was.

This century, Ronde Barber most certainly is at the top of that list. The longtime Tampa Bay Buccaneers cornerback — like safety LeRoy Butler — is a finalist for the Pro Football Hall of Fame. And, like Butler, he has one hell of a case to make. No defensive back in NFL history started more consecutive games than Barber whose streak, including playoffs, lasted 224 games. Considering he’s throwing a 5-foot-9 frame into harm’s way, weekly, that’s pretty insane.

He produced. Barber was a five-time All-Pro and the only DB to ever finish with 45-plus interceptions (he had 47) and 25-plus sacks (he had 28), in addition to 12 touchdowns, 1,251 career tackles and, of course, that Super Bowl title in 2002. His interception of Donovan McNabb in the NFC Championship Game may be the most iconic play in franchise history.

In our chat this week for Throwback Thursday, Barber hit on just about everything: How his “wrestling”-like tackling form helped him last, gritting through a torn PCL that Super Bowl season, still hearing from angry Eagles fans today, why the Super Bowl win over Oakland was a “foregone conclusion,” his thoughts on these 2020 Bucs, why we should all view the cornerback position in a totally different way and, yes, why Barber believes he should be mentioned right there with Charles Woodson and Champ Bailey in his era.

It’s hard to argue with his case, too.

What are you up to these days, Ronde?

Barber: Really, nothing. I can honestly say that for the first time since I was in high school, I am working on nothing right now. It’s actually been refreshing. Last year was my last year at Fox. My contract ran out. So for the last 23 years, I had some tie to professional football. And in the last eight months, I’ve been doing a whole bunch of nothing. Golfing. Doing some digital stuff with the Bucs. I’m still engaged with my home team pretty deeply. But otherwise, not a whole lot.

That has to be a nice change of pace. Do you enjoy taking a step back or do you miss it at all?

Barber: No, I thought I would miss it but it’s refreshing. Even doing TV, the weekly grind from Monday to Friday — before you leave — it’s like work, it’s like preparing to play on Sunday. And then you have to work when you’re in the booth. It’s been nice, mostly, because I have a daughter who just left for college. I have another one who’s leaving for college this year. I’ve got my 20th anniversary. All of the little things I thought I was going to be too busy to do, I’ve got time to do ‘em now. I’m on the board of the Valspar Championship which is hosted by the Copperhead Charities. I’m taking over Copperhead Charities next year as their general chair. The timing is perfect to take a step back from being so deeply involved with professional football and chase some of these other interests.

As far as football goes, you really transcended era to era to era playing as long as you did, for 16 seasons. When you look back at your career, what are you most proud of?

Barber: That, for sure. Being able to play as long as I did. I didn’t start right away. I was a third-round draft pick that played in one game as a rookie in ’97. I did end up playing in one playoff game as well, so two games my rookie season. Only dressing two games my rookie season. To, the following 15 years, starting 245 of those games over the next 15 years and always answering the bell. I’m always proud of that — the durability. The availability I was able to sustain for a long period of time. The uniqueness of what I did is not lost on anybody. Anybody who looks at the numbers can say, “Damn, dude, you did a whole bunch of a lot.” I was a master of a bunch of different aspects of the game. And I’d like to think that not a lot of people — or, any — have done it better. I’m proud of that and I think people understand what my contribution to the game was. Tampa and Monte Kiffin and Tony Dungy, their scheme allowed me to do a lot of different things. I seemed to thrive in it.

Start with that durability. We talk about Brett Favre’s record so much but, playing the position you played, you’re smacking into bodies and getting smacked around more than him. That’s the record for defensive backs in NFL history and we probably don’t talk about it enough.

Barber: No, no. It’s not like I was getting two or three tackles a game. There were many games where I led our team in tackles. I was a perennial, 100-tackles-a-year guy. And so it’s not like I was absconding contact. And a lot of times, I had to search it out. And, for that matter, it was expected. I remember my defensive coordinator was very adamant about, ‘If you’re not going to hit in this defense, you’re not going to play.’ It’s paramount to the success of the defense that our corners — especially our nickel corner — be physical players and be wanting to make those tough tackles on the edge of the defense. And I took it to heart. I realized I was kind of the under-appreciated guy and I was going to have to do more than anybody else was willing to do so I could keep my job!

And then you get good at it. You start perfecting your craft. Tackling became easy. Tackling became second nature to me.

How though? You’re playing in a different era and you’re a generously listed 5-10, 184?

Barber: It’s 5 foot 9 and 5/8s and, once the game started, I was probably 179. I wasn’t big. It was about perfecting technique and doing things efficiently. And then, I swear, it was as simple to me as hitting the ball-carrier — whether it was a tight end, a running back, a receiver, whoever — just hitting with my chest plate and grabbing onto anything. And coming up with a body part. Hit him with your chest and come up with a body part. That was it. And in that way, you keep your head out of it. You don’t really hit him with your shoulder. There are times your shoulders get involved, when you’re cutting somebody low or going into a pile. But almost all of my solo tackles — anybody can go back and look at the tape and see how many times I hit somebody with my chest. My head’s up. My arms are just wrapping around something. A leg. An arm. Midsection. It didn’t matter.

I was talking to Johnathan Abram a few weeks ago. He’s obviously throwing his body all over the place and we’ll see how long he lasts. But he said in trying to change his style of play, he’s trying to hit with his chest, too. How do you hit with your chest? I couldn’t really picture that.

Barber. In technical terms for a DB, if you’re running to make a tackle, you’re long-striding. You’re running as fast as you can. At some point, you short stride and you start shuffling your feet a little bit. You kind of shuffle and lower your body. And then you always hit on the rise — hit up. So you’re basically squatting out of that staggered stance that you get into, and then hit him with your chest. Don’t hit him with anything else but your chest on the way up. And that creates some force which is going to match that opposing force and then you just hang on and fall to the ground. Wrestle his ass to the ground.

People ask me what was my favorite sport growing up, and I tell them wrestling. I didn’t play basketball during that season. I wrestled. And wrestling probably made me the toughest son of a bitch that people have ever seen. It’s such a gritty, nasty, man-on-man, find-a-way kind of sport. And a lot of the way I tackled came from wrestling in junior high. Guys who play defense that wrestled, I can almost always tell just by the way they grapple. You can see it.

Maybe you were at the forefront of this then. I imagine not a lot of guys were tackling this way.

Barber: You know who it was, was (John) Lynch. At the beginning of Lynch’s career, he was a headhunter. He was laying people out, including his brother-in-law. He’d always lower his level and drop his head and kind of hit people with the front crown of his head. Things that would get you kicked out of football games nowadays. And I remember, around ’99 or 2000, him really taking a step back and evaluating how he did things. Mainly because he was starting to get fined for it and he was going to hurt himself. He was going to hurt his neck. So he was the one who I watched make this transformation — long stride, short stride, staggered feet and hit on the rise with your chest. And he’s so big that when he does it, he kills people.

But I was like, “I can adapt myself to do the same thing.” Just wrap up and grapple somebody to the ground. They’re not going to be able to shake my 179 off of them if I grip tight enough. It’s a part of the game that nobody talks enough about. It’s not the most glamorous thing to talk about in the broadcast booth. But tackling is as much an art of the game as anything.

Starting all of those games in a row, what injuries did you have to play through to keep the streak going?

Barber: The streak should’ve been even longer than that. But there was a game, I think, in ’99 where I pulled a hamstring the prior week and they asked me if I was ready to start on Friday. I was like, “Eh, I don’t know.” I was limping through practice. I could’ve probably have started but I said, “Why don’t you let Brian Kelly start this game.” Brian was our third cornerback at that time and ended up being a starter in our Super Bowl year. I said, “Why don’t you let Brian Kelly start and I’ll just play third downs and nickel stuff.” And then we get to the game and I’m like, ‘F---, I could’ve started.’ My hamstring was fine. But it broke that streak which I wasn’t even thinking about at that time. It was still very early in my career. After that game, I was like, “It’s going to take a significant break of a lower-body extremity for me to miss another start.”

And that’s what it was. Our Super Bowl year, I broke my thumb the week before we played Green Bay. I had surgery on Monday. I practiced on Wednesday and had an interception on Brett Favre that weekend. I tore ligaments in the back of my knee that Super Bowl season. I tore my PCL, said “F--- it,” and played right through it. Many, many minor soft-tissue injuries that I just limped during the week to try to remedy. And I did what I had to do Sunday morning to go play.

I refused not to be on the football field. I felt like I was better than the guys who were behind me even if I wasn’t 100 percent — just because of my knowledge of the game. There wasn’t anything I wasn’t going to be able to compensate for, at least I felt that way. My coaches probably didn’t believe that. I remember Mike T and Monte talking, “Look at this dude. He can’t even walk in practice. We’re going to start him on Sunday?” Mike (Tomlin) was like, “Hey, man, don’t worry about it. He’ll be there on Sunday.” I always answered the bell, man.

Mike Tomlin? He was your DBs coach then, right?

Barber: Mike is my guy, man. He was great for me. Herm Edwards was my first DBs coach when I first got into the league, in ’97, and obviously Herm had a great, storied pro career. But he was really philosophical about the longevity it takes to play in the league — “You could be driving a truck next week if you’re not on your business part of this game!” type of thing. But when Mike came in (2001), he put a different type of belief in me that I was really who I ended up being. I don’t know if I saw myself that way before he got to town. He’s like, “I watched all the film. I watched two years of Bucs tape.” And I was a free agent at that point when he came in and convinced me to come back. He said, “You’re essential to this defense. I have not seen anybody do what you do. If you don’t come back, I don’t know how I’m going to replace you.” He was the one who put in my head, “Hey, man, you know you have 10 or 12 sacks. I don’t think there’s been a corner who’s ever had 20.” So that was a goal. So those little minor things drove me to greatness.

So many players point to him as the standard for coaching today. He convinced you to stick around?

Barber: I just didn’t know. I didn’t know how they thought about me. That year, there were three big free agents. Jason Sehorn, who ended up signing back with the Giants. Ray Buchanan with the Falcons. They signed six-year deals worth over $30 million. I’m thinking, “I’ve got to be close to that number. The Bucs are offering me basically half of that on a six-year deal. I’m like, “Damn, are you kidding me?” So we tested the market. We went to Cincinnati. We got a look from Seattle. But I ultimately ended up signing back and it was the right thing to do, to come back to Tampa and prove myself. I got f-----, though, because the year after I signed my contract — which was six years for $18 million — that next year I led the league in interceptions. The ink hasn’t dried on my contract and I lead the league in interceptions. I make my first Pro Bowl, first All Pro, Defensive Back of the Year, finished third or fourth in defensive player of the year voting. And I’ve got five years left on a contract that is grossly under-paying me.

Today, they’d just demand a new contract.

Barber: One-hundred percent they would. But I will say, playing that contract out probably helped me. Because when I was 31, Bruce Allen, who was the GM at the time — Rich McKay was my prior GM — Bruce was like, ‘Man, you can play here as long as you want to.” At 31, he signed me to a long-term extension with the most money I had ever made. And it’s part of the reason I played for so long and played here for so long. I had invested a lot into the emotional bank account of the team. The team was tied to me at that point. Basically because of my play and because of how I helped them out along the way.

The PCL. The thumb. Not being able to walk in practice. Which injury was the worst you think?

Barber: The PCL. The PCL was a pain in the ass. That was an actual torn ligament, the one you need as a stabilizer. It stops your knee from hyperextending. I didn’t have it. I wore a brace on it for a little while. Your body’s a miracle. It learns to defend itself. So, structurally, my knee started to change and it was always filled with fluid to protect itself. So I had to always get that drained out. Take anti-inflammatories.. And then you get to Sunday and just live off of adrenaline. The problem was that it lasted two years. I got it cleaned out after the season. They couldn’t repair the PCL. The cycle of play or practice… and it’d fill up the knee. Barely be able to move it. Heat it up. Move it around. Go play or practice… and the fluid comes back in the knee. That was a daily routine for me, for basically two years of my career.

That was the Super Bowl year, right?

Barber: That was the Super Bowl year, and the ensuing ’03 and ’04 seasons after that I was dealing with that pain.

To play on, to chase and get that ring through this all, there has to be no greater feeling.

Barber: There was no way I was missing it. I knew we were on a run. It felt right for us that year. We had been close in ’99 and this felt like a more complete football team with the right attitude and the right focus to win. I was like, “I don’t care what it takes to play. I’m playing. There’s no way I’m missing this.”

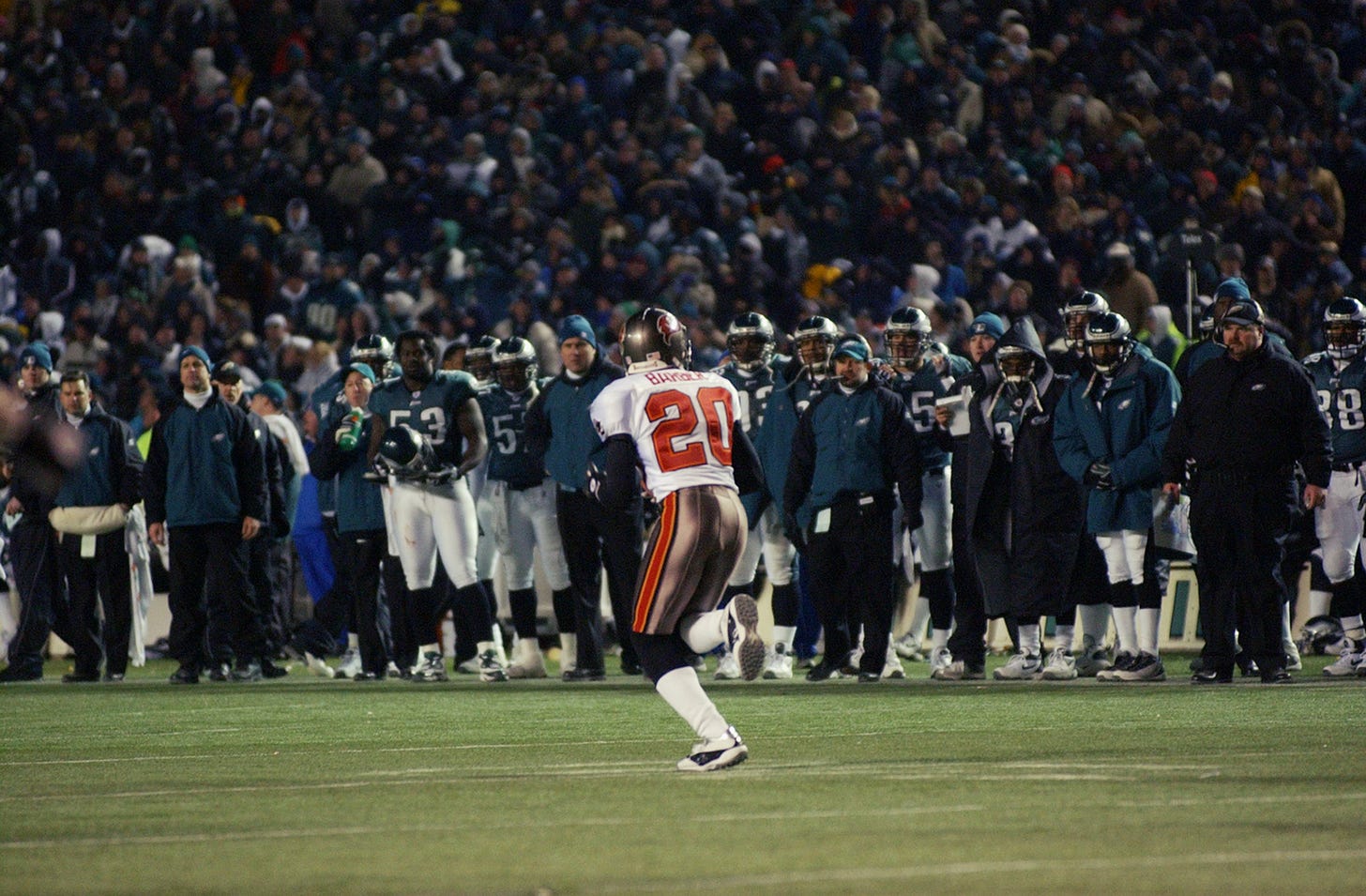

That 92-yard interception return to get to the Super Bowl—that play at Philly—has to be right up there for you.

Barber: That’s the play that defines me. For a lot of Bucs fans, that’s the play that defines that championship team. Obviously there were many great plays that season. Derrick (Brooks) was the defensive player of the year that season. He had five interceptions and three of them were for touchdowns — during the regular season — and then he had the one during the Super Bowl, too. So there were tons of defining plays for us that year. But that one, for me, and for a lot of people who know Bucs history, that’s the biggest play in Bucs history.

It’s the biggest play in Bucs history and, up until they won the Super Bowl, it was the defining moment in Philadelphia Eagles history, too, wasn’t it?

Barber: (Laughs) Trust me, I know. To this day, I get people who say, “You ruined my childhood! I’ll never forget you!” And then there’s, “Hey, you’re cool as hell but I hate you.”

You still hear from people?

Barber: Oh yeah. There’s a guy who is the director of sales at the golf club who’s from Philly. He brought it up to me today. Because we were talking about the Bucs going back to the championship game with the chance to go to the Super Bowl. He brought it up, like, ‘Ah, God, you and championship games.”

There was a rawness to it. That was their year and their last game at Veterans Stadium. You ruined their dreams.

Barber: They were a playoff team for like five or six years in a row. They were in it, dude. The fact that they didn’t win one for another, what, 14 years is crazy.

What made that defense special in NFL history?

Barber: Schematically, we were pretty simple and sound. We knew what we were doing. There wasn’t a situation in any game — talking about situational football, first down, second down, third down — we didn’t understand. We had been coached that well. And, obviously, that isn’t something you learn in a year. That’s something you learn over time. And probably from ’97 to 2003-2004, it was basically the same nucleus of guys. Every year, we built on more and more knowledge of situational football. So you add into the fact that we didn’t do a whole bunch on defense. We had like nine or 10 calls.

That’s it? Nine or 10?

Barber: That’s it. We played a bunch of Cover 2. We had some zone dogs. We had some strong or weak rotations and three deep and we played some man and one lurk. Otherwise, it was simple. And because it was simple, everybody knew what to do in every single situation against every formation. Whatever was brought to us, we had answers. We had a ton of walkthroughs. And then you add on top of that, some pretty damn good talent. Some generational type talent in Warren Sapp, Brooks, Simeon Rice and Lynch and myself and Brian Kelly — who that year led the league in interceptions — to Dexter Jackson, the Super Bowl MVP.

Going into the Super Bowl, you’re facing the MVP in Rich Gannon — and they’re lighting teams up left and right — but your confidence had to be through the roof. Did you know exactly what would happen that night?

Barber: For sure, man. Oakland’s offense, the way it was designed — the West Coast offense with all the quick passing — our defense was really designed to stop that. That’s what base Cover 2 was designed to stop. With that Mike (linebacker) running through the middle of the field and the seam droppers taking care of all of that underneath traffic. You had to have great athletes which it was me and Brooks in there on those drops. It was set up for us. We knew how to attack that offense. And, really, the Super Bowl — and I hate to dismiss Oakland going to the Super Bowl — the tough game we knew was the NFC Championship Game. Going to Philly was the tough one. We had lost to them twice in the playoffs the previous two years. Our coach, Tony, got fired. We went up there earlier in the 2002 season and lost. It was like, “We have to beat Philly. If we don’t beat Philly, we’re nothing.” Once we beat Philly, in our minds — and I know you still play the game and it’s probably a hyperbole a little bit — but it was a foregone conclusion that we were going to win the Super Bowl. We just knew after we beat Philly that there was nobody who was going to beat us.

We were running hot. We won games with Rob Johnson at quarterback. We had to kick four field goals in Carolina. We had to go to Champagne, Illinois to play Chicago in Week 17. We dealt with everything. There was nothing that was going to stop us from winning the Super Bowl. The Super Bowl was kind of boring to be honest with you.

What do you want your legacy to be? What do you think it will be over time?

Barber: I think people look back and say, “He was the best nickel cornerback of that generation.” Obviously, the game has changed a bunch since I played. And that’s only eight years ago. There’s a lot more going on. But during my era, I don’t think there were many who did it better. A lot of people tried to call that a “system,” and that was the only “system” I could play in. I’m quick to remind them that this system was the one everybody wanted to be playing. The other great defense of that time was Philly and they played a similar system. Carolina, who had much success right after we did, basically emulated our system. They got the same type of players and everything to run our system. St. Louis took Lovie Smith to be their defensive coordinator and they were running our system. So, at that time, there was nobody doing what I did the way that I did it. And I think a lot of coaches and personnel people at the time would look back at that era — late 90s, early 2000s, much of the 2000s — and say the best inside player during that decade was definitely me.

It’s probably why I’m on the All-Decade Team, because of the unique things that I did during that time.

The All-Decade Team. The numbers. The memorable moments. It’s all there. But it’s weird because, for whatever reason, you are overlooked. Is it the bigger personalities on those Bucs teams? Or maybe the fact that you have a twin brother, Tiki, running for the Giants. Are these other factors subconscious for people?

Barber: I’m sure, I’m sure. If you’re not the first-round draft pick — and the can’t-miss guy — it’s hard for people to say that you achieved the same thing as that guy. My peers, in my era, were Charles (Woodson) and Champ (Bailey). Those were the two guys. And there’s plenty of others, like Ty Law. Those are the two guys who are on the All-Decade team with me. If you look at their numbers and look at my numbers and look at the myriad factors that made them great players, there’s an argument there. If you just look at the numbers. And that’s not even putting the game on and seeing the impact I may or may not have had — just put a game on and see the impact I had in that one game and say, “How does that compare to those guys?” It could be because we have two Hall of Famers and John Lynch is an eight-time finalist for the Hall of Fame. Simeon Rice was a can’t-miss player.

There could be a lot of different factors why people didn’t really respect me.

But probably the big thing is that people think corners traditionally have to look one way. They’ve got to be tall, long-armed shutdown corners that play on the line of scrimmage and take away one guy. That shit doesn’t work in the NFL anymore. So I don’t know why we’re still perpetuating that myth. There’s one dude who did that, literally, one frickin’ dude in the history of the league that did that and can say he was the best in the world at it, and that was Deion. He was the only guy that I know who did that.

Even the guys in prior eras, were multi-talented guys playing different types of defenses. Offenses weren’t nearly as complex. So if you were Lester Hayes or one of these old-school, LOS-playing corners, you didn’t have to do anything but take away one guy. But as football evolved, you had to evolve as a player. But peoples’ mentalities have never evolved off of that 80s and 90s and Deion-type of shutdown corner. People keep wanting to say “shutdown corner,” but that doesn’t exist anymore. That just does not exist. It’s a fallacy to even say it nowadays. The best in the league right now play zone. They play man but they play a ton of zone, too.

Jalen Ramey?

Barber: Yes, all of them. All of them. Name one. Patrick Peterson. All of them. Patrick used to be great at the line of scrimmage and he would take away guys’ routes and he had great speed. But if you put on the film now, Patrick is playing zone coverage. Richard Sherman is a great interceptor of the football. He plays almost all zone coverage. That’s not a knock against him — that’s what he’s good at! He sees the ball. He’s bigger and stronger and has great receiving skills. He goes up and takes the ball away. I think people want to tie you into a narrative and say, “You’re not that guy. You can’t be great.” In reality, the evolution of the game and the way I evolved the game to suit my talents is what people should be giving me credit for. But for some reason, they don’t want to.

I just pulled up your numbers next to Champ Bailey and Charles Woodson and they’re not that much different. You can have that argument, couldn’t you?

Barber: I’m telling you. You can. I have it with my friends all the time. They want to bring it up all the time — “Alright, guys, I get it.”

So what would you say then? Those are two guys that felt automatic — first-ballot, get ‘em in.

Barber: Because of who they are. Because of the reverence that the general public (gives) and writers, who can be sometimes lazy and not thorough enough in their research and knowledge of the game to say, “He was impactful in a different way.” That’s what I tell people about Charles because Charles was probably my closest peer in terms of numbers and things that we did. Because he had the 20 sacks that he ended up getting. He would make plays around the line of scrimmage because when he was playing for Green Bay, he was playing very similar to the way I was playing. He was playing that nickel inside position so he would rush, he would cover, he would have to play zone and you look at our numbers, our numbers are the same. I’ve got more touchdowns. He’s got more interceptions. I’ve got more sacks. I’ve got more tackles. I didn’t miss any games. He only missed a handful.

So if you’re looking at Charles — and this is the argument — and people say, Charles is a Heisman Trophy-winner and a first-round draft pick and rookie of the year and All-Pro 12 time or whatever. I say, “Yeah, that’s what he was supposed to be. That’s exactly what Charles Woodson was supposed to be. And he fulfilled his potential. What was I supposed to be? As a third-round draft pick? Was I supposed to be a five-time All-Pro, five-time Pro Bowler, the only guy in history to have 45 (picks) and 25 (sacks)? Was I supposed to be that? So if you want to make the argument, you could make the argument that I was the better player because I more overachieved than Charles achieved what he was supposed to be.

If you can rationalize that argument, that’s my argument.

You’re a 66th overall pick out of Virginia. People don’t really know who you are — they probably knew Tiki, not Ronde.

Exactly.

The fact that only five get in (to the Hall of Fame) every year makes it difficult on so many deserving guys. It’s always going to be that way. It’s the crux of the problem. It’s a hallowed hall for a reason. That’s why the jacket’s gold, dude.

What’s going to happen with the Bucs on Sunday at Lambeau Field?

Barber: I think it’ll be a game. The Bucs have exorcised their one demon, and that was slow starts over the past month. They’d put themselves in such a bad position at the beginning of games, and then they’re always fighting themselves out. It happened in Chicago. It happened in almost every game where they struggled and lost. I would say over the past month of the season, they’ve found some balance on offense. They legitimately have a good offensive line and a really good running game — Ronald Jones is a stud, Leonard Fournette had a great game last week. You’re talking about elements that help you win in cold playoff-type situations and they probably have the best wide-receiver room in the NFL.

You have to like their chances, just because of their personnel and that they’re playing their best football in December.

The defense worries you because of those young corners in the secondary. The scheme can be somewhat complex and if you have any breakdowns in that scheme, that frickin’ Aaron Rodgers is going to take advantage of you. He’s going to find a way to beat you. To me, that’s where the game is.