The Real Romeo

Romeo Doubs is taking these playoffs by storm. We sit down with the wide receiver who escaped South Central Los Angeles. He's unlike anyone else at his position.

I: 'You’ve got to see who I am'

GREEN BAY, Wisc. — There’s mystery to the man. The public’s been supplied jigsaw pieces to this point. Not the social-media pandering encouraged at this position.

Romeo Doubs was a human machete making incisions all over the Dallas Cowboys’ secondary. Curiosity turned to awe for those who hardly knew No. 87 in green, which is most of America. After Catch No. 1 at midfield, the wide receiver did not tomahawk-slam the football into the most famed star in sports. He gently dropped it with zero emotion. He caught six for 151 yards in all — a clinic. By the end of Green Bay’s 48-32 wild-card romp, Doubs nestled between four bodies in the end zone to catch a touchdown and his celebration was muted.

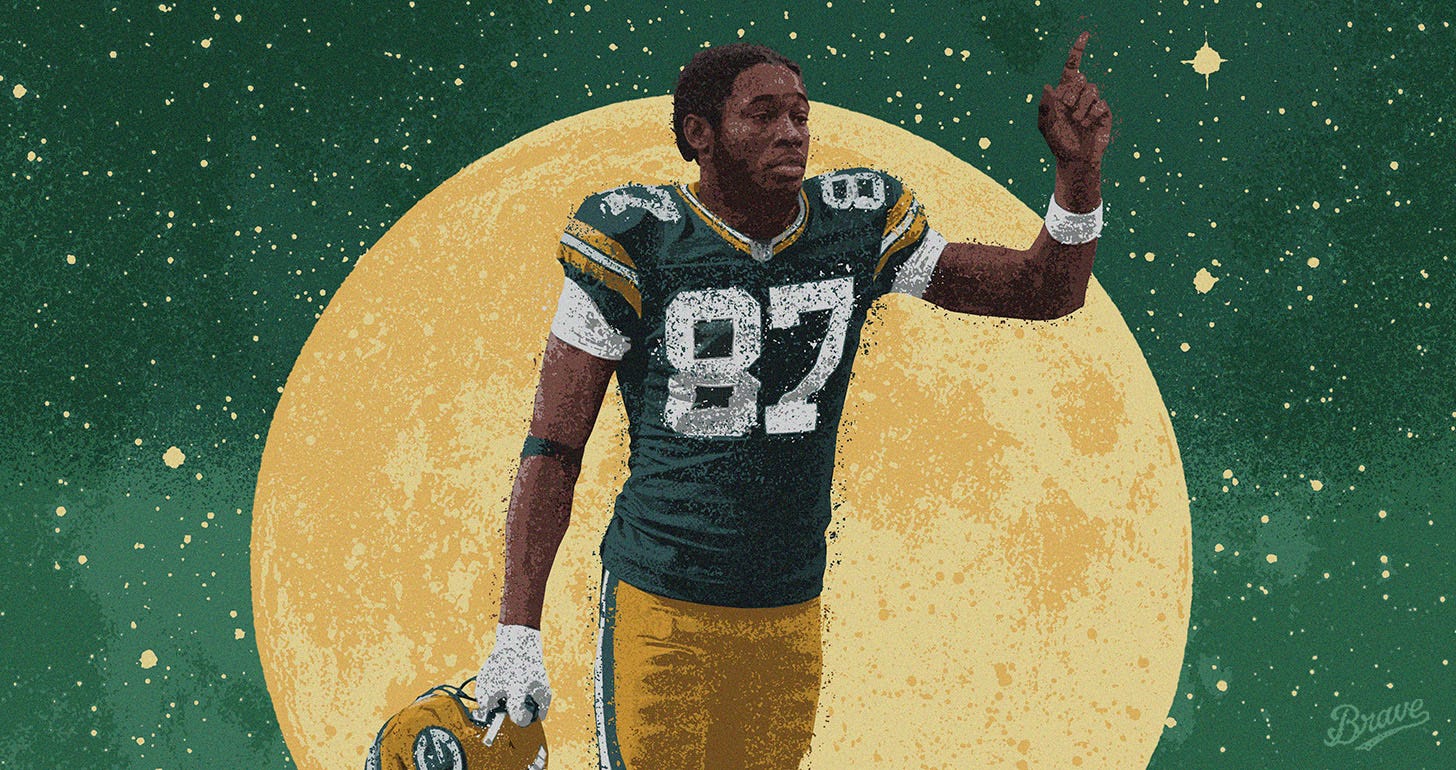

Holding a No. 1 to the sky, Doubs hustled off the field before teammates could converge.

He is quiet. Extremely quiet.

He has hinted at a hard upbringing in South Central Los Angeles. Vaguely.

This former 132nd overall draft pick out of Nevada was even an oddity to NFL scouts, investigators by nature.

Fascination around these Green Bay Packers only grows, as a team in alleged rebuilding mode scripts its own story. These 22-, 23-, and 24-year-olds on offense resembled a juggernaut in Big D. The quarterback is an equal opportunist — there are no favorites — but Jordan Love makes the most magic with this 6-foot-2, 204-pound receiver, this father striding through the entrance of Republic Chophouse in downtown Green Bay. Doubs brings his longtime girlfriend, 9-month-old daughter and the scenery’s ripe for manifestation a few days before that Cowboys playoff game. The perfect time to stare ahead, squint and envision such greatness. For himself. For his family. For the Packers. Malani is cozy, napping inside the carrier. Lights are dimmed. Steaks are ordered. Soft music plays. Doubs speaks in a low hum — you need to listen intently — and each word is carefully crafted.

Only… he does not manifest. Because he is no dreamer. He never pictured the National Football League as a pot of gold waiting for him at the end of some treacherous underground tunnel. Football is changing his life but it’s not as if Doubs charted out a master plan at age 14. Simply, he made the right decision over the easy decision — repeatedly — in L.A. One workout, one practice, one game at a time, Doubs forever lives “in the moment.” Initially, Doubs says this is how all pro athletes think, but he’s wrong. He is different. Drastically different than his wide-receiver contemporaries. Because over two full hours, not only does Doubs refuse to build himself up. Doubs refuses to even discuss his game. Period. Asked what separates him as a player — perhaps that tenacity on contested catches? — he recoils.

“The biggest thing, man, is not talking about it,” Doubs says.

His girlfriend, Andrea, chimes in: “He doesn’t like to brag.”

Dominating the cornerback across the line demands alpha arrogance. This is pure 1-on-1 combat and the best of the best weaponize their mind to instill fear. They’re marvelously malicious: Mike Tyson walking toward the ring. Apex predators in the wild. Trash-talking characters obsessed with earning universal “Him” status. Bare minimum, a wide receiver will at least explain why he is… um… good.

“I stay away from talking about it,” Doubs says. “Because I know the moment I do, bad things usually happen. The mindset’s different when you don’t talk about it. You’re now in the progressive mode of, ‘OK what can I learn from this? What can I do from this?’ Compared to talking about it. Now, you really look like a fool.”

Go Long is your home for independent longform journalism in pro football. We’ve love to have you join our community today.

Subscribers can access all stories, all podcasts:

He’s in no rush to meticulously detail the traumatic journey from Los Angeles to Green Bay, but he gets there. Doubs ever so gradually unlocks those memories and — when he does? — all those plays on the screen make sense. A true portrait emerges. Friends have died. Family has spent time behind bars. He evaded the trappings of South Central L.A. with more elusiveness than any defensive back will ever encounter on the field. He linked up with longtime coach Terry Robiskie — via mentor Keyshawn Johnson — and hardened into a different tier of worker.

He became a father, a miracle itself. Romeo Doubs takes a long look at Malani and does the quick mental math. Green Bay? Raising a baby girl? Starting in the NFL?

“It’s insane, man,” he says. “Not a lot of people really get to know me, as far as allowing people to get to know me. It’s nothing personal. I stay in my lane and hope it doesn’t poke other people.”

There was one week he needed to open up. Too much is on the line for NFL teams. Every draft pick is an investment. They absolutely must figure out how you’ll respond to adversity because adversity is a guarantee. Lord knows Doubs conquered his share, but GMs, coaches, scouts left the 2022 NFL Combine with a warped vision of Romeo Doubs.

Notes filling scouting reports described a completely different person.

This week in Indianapolis was a total nightmare.

He cannot remember the exact meal that shut down his body, only that it was absolutely something he ate upon landing in Indianapolis. If he digested a stick of dynamite it would’ve been more pleasant.

Ninety minutes after dinner, Doubs walked toward NFL personnel and coaches gathered in a big room for informal interviews and his stomach started to “bubble.” He got chills and started calling everyone he could. His girlfriend. His mother. “Everybody,” Doubs says. Across the table, Andrea’s eyes widen. Their FaceTime chat was something straight out of a horror movie. (“He was sick.”)

All symptoms from a severe case of food poisoning.

Tonight is the first time he’s sharing this information with anyone outside his inner circle. Mostly because Romeo Doubs has tried to wipe that week from his memory. He never saw any reason to explain himself to teams after the fact, but it’s true. Exactly when Doubs began interviewing for a job in the NFL, he endured some of the worst pain of his life.

“Stomach hurting. Chill bumps. Sweating,” he says. “Couldn’t really think straight. It was bad. It was terrible.”

This was not merely one team interview, either. If so, the damage to his reputation would’ve been isolated. Minimal. No, this informal setting in Indy is more of a rapid-fire NFL speed date. He cannot remember the exact number, but Doubs estimates he met 10 to 15 teams, stammering through conversation all along. One bad meal and teams were referring to this all as a “mental breakdown,” he recalls.

He was sick all week. Lost 10 pounds in all.

One of his greatest strengths — his mentality — was suddenly ridiculed as a weakness.

Doubs knew it wouldn’t matter what he tried telling teams later, especially when bad turned to worse. That night, Doubs tossed and turned and couldn’t sleep with the chills. He remembers staring at the time — 1 a.m., bled to 2 a.m. to 3 a.m. He could not sleep… until he did. Until he overslept. The phone in his hotel room went off and, yikes. Doubs was late for his drug test.

“I was just like, ‘This is bad,’” Doubs says. “Once you have more than one person with the same mentality or the same exact mindset against one person? Explaining doesn’t help anything. You’ve got to live with it and then whatever persona they put on you, let it be put on you.”

He’s not exaggerating. One AFC scout told our draft analyst Bob McGinn that he deemed Doubs “mentally frail” before then adding: “He wigged out at the Combine. He had so much anxiety and apprehension that he stayed in his room and never came out. Did not participate in the combine. After the initial day, he never came out. That was very much a concern that our scouts had. He's probably no better than a third day guy at best.”

Other scouts offered versions of the same takeaway. Word of an “anxiety attack” spread.

Despite growing up in a city littered with pitfalls around every corner, he kept a squeaky-clean record. He wasn’t entering the NFL with a rap sheet like so many others. The fact that he made it to a four-year college was a monumental accomplishment in his family. Frail? If only those scouts witnessed one of his workouts with Terry Robiskie.

Thinking back, the stoic Doubs becomes visibly irritated.

This felt like being wrongfully accused of a crime.

“That narrative got switched fast and there was nothing I could do,” Doubs says. “I just had to deal with it like, ‘Man, this is the NFL. Is this kid really strong? Can this kid do this? Can’t this kid do that?’ That’s the first thing y’all think about? At that point, y’all can say what y’all want because — at some point — you’ve got to get to know me. You’ve got to see who I am.

“That was probably one of the craziest times of my entire life.”

He wishes he could’ve sat down at a steakhouse with a representative from all those teams. Only then would they get the full picture. If he could go back in time, OK, he would’ve eaten something different. Other than that, Doubs wouldn’t change a thing because it’s impossible to show anybody who he is in 10-to-15-minute increments. He knows the league is bigger than him, too, so he also doesn’t even blame scouts for penning such scathing analysis. It’s their job to investigate how players are wired and there’s a very good chance they’ve seen players experience very real mental breakdowns that are justifiable red-flag warnings of trouble to come with 2 minutes left in a playoff game.

Teams need employees who can handle the reality that the NFL is cutthroat.

But Romeo Doubs also knows a slew of NFL teams had Romeo Doubs dead wrong.

He left Indy without a clue what’d happen next.

There is no sugarcoating life in South Central.

“It’s not a safe place,” says Doubs, plainly.

He doesn’t want to slap stereotypical labels on his neighborhood because there’s trouble in all metro cities. But gang life is more than a fringe reality in Los Angeles — it’s a lifestyle that swiftly and savagely absorbed so many of his childhood friends.

Take Jordan Patterson. They played Pop Warner together. Grew up in the same area. Patterson, a safety, even developed into one of the top recruits in the city. “Before you know it,” a despondent Doubs laments, “he becomes a gangbanger in the city of L.A.” Patterson was sitting in his sedan shortly after 12:45 p.m. on Sept. 30, 2020 when another vehicle pulled up beside his car and opened fire, per the LA Times. A UCLA commit at one point, the 19-year-old Patterson was pronounced dead at the hospital.

“I know his family,” Doubs says. “Even just talking about it, it traumatizes me.”

He’s silent for a few seconds before then mentioning another friend: “Rob.” They, too, met in Pop Warner. Rob became a gangbanger. Rob was killed in high school.

“I try to stay away from the conversation, try not to talk about it again. I’m a deep thinker and obviously I zone out and just… moving on.”

But Doubs can’t move on. These emotional wounds never healed, so he cannot pretend like they do not exist. All L.A. trauma helps explain his rise. He never witnessed anybody get shot and killed but it’s a miracle he didn’t suffer the same fate considering everything at home. He first points to his uncle’s death in 2007. His mother’s little brother was a rock in their lives.

That same year, both of his parents went to jail.

His mother was released after a year and a half. No further details are shared.

His father was a different story.

“My dad,” Doubs says, “was actually on the run. And then he ended up getting caught up. He went in for about six, seven years.”

A quick search reveals that Jarmaine Doubs Sr. was wanted by police for attempted homicide, assault with a deadly weapon, robbery, terrorist threats and kidnapping. U.S. Marshals led a strike team. Along with two relatives, per the Las Vegas Review-Journal, he was accused of attempting to murder a woman named Elaine Neal because they believed her son killed another member of their family.

Looking back, Romeo is grateful all of this happened when he was so naïve. He was only seven years old, just young enough to not understand what was happening.

“You don’t really get that feeling of struggling or understanding what hurts you,” Doubs says. “If I was old enough to witness that, who knows who you become as you get older?”

This is not an uncommon upbringing. Sadly, every child in the eye of such a storm is vulnerable. That’s why Doubs sounds demoralized — no, defeated — thinking back to childhood friends who became “that guy” into high school. Everyone knew Doubs played football and, typically, that was enough to keep gangbangers at bay. But not always. There’s a saying in L.A., he explains: “Getting banged on.” Gangsters who knew Doubs would still approach to ask for his affiliation. Bloods? Crips? The question is posed as a threat.

Once, Andrea was with Romeo. She recalls someone rolling up to them both on a bike with a backpack turned around front. His hand reached inside that backpack, likely gripping a gun. “Are you from here?” he asked. Doubs kept walking as Andrea — a girlfriend who takes no shit — said, “Don’t we go to school together?” He rode away on his bike.

The hair may be standing up on the back of your neck. Doubs knows this all sounds chilling to those unfamiliar with this world.

Honestly, though, he gets it. Kids like this are reppin’ a gang and following orders.

“No different than having a general manager,” Doubs says. “You work for somebody. You’re under somebody’s construction. You’ve got to do what they say or you get the consequences.”

Striking juxtaposition sitting here in Green Bay. As Dad lays out this blunt reality for teens back home, his daughter wakes up from her nap. Mom gives her sips of water from a straw. Ray Charles’ playful “Hit the Road Jack” plays over the speaker. Both are thankful to raise a family in such a small community because both saw how easy it is to free-fall into a gang. Romeo always had sports. Even then, it’s easy to find yourself around the wrong group of friends.

One hangout, one conversation, one domino is all it takes to organically spiral into that world.

“Imagine I was here,” Doubs says, ominously. “Imagine if I was hanging out with this person, rather than running sprints with the team. Because as a teenager — those decisions in those moments — especially when you don’t want to do anything, it’s easy to just be like, ‘Oh no, I’m not going to practice. I’m finna go do something.’ And then that one time turns into three times and then three times eventually five, then seven…”

Next thing you know, that gang is your family.

They provide protection, identity.

Next thing you know, you’re setting down the football and putting on that backpack.

These are not joyous hypotheticals for Romeo Doubs, but this is also a wide receiver who was coughing up blood during the Packers/Bears game before this chat. He suffered a chest injury and went to the hospital afterward for testing. Earlier this season, he played through a hamstring injury that was more painful than anyone realized. Even the 23-year-old who’d rather undergo a root canal than discuss his own qualities admits L.A. is what made him so mentally tough.

All of this, he adds, taught him “to stay 10 toes down.”

He wasn’t perfect. There were times Doubs found himself saying internally, I’m not supposed to be here. But as far back as he remembers, someone else usually stepped in to say: “Nah, you stay back.” Everybody — “everybody,” he stresses — recognized his burgeoning athletic talent and collectively shielded him from danger. That’s where the most dominating presence in his life entered the equation. Peers knew how downright pissed his older brother would get if he found out Romeo was slumming around the wrong crowd.

Jarmaine Doubs Jr., aka “ManMan,” refused to let Romeo steer off track. Romeo estimates his big bro is 75 percent the reason he never domino’d into that “three times… five times…” trap. The age difference helped. Four years older, Jarmaine Jr. went through the football recruiting process a full cycle before him. Carved out a nice football career himself, from junior college to Southern Utah to the Arizona Rattlers of the Indoor Football League. He passed along advice he never received himself.

“That’s why I salute him,” Romeo says. “Some may say I did the dirty work, but he literally did the dirtiest part, just from taking the hardest road.”

Back home, Jarmaine Jr. is asked constantly why his little bro was the one to make it to the NFL and his answer is always the same. While Jarmaine Jr. was willing to share words of wisdom with anyone who’d listen, Romeo was the one who took advice to heart. Every teenager wants to “roam out,” Romeo adds, but few are willing to put the work in. The crux of everything — How did Romeo Doubs get to Green Bay, to this moment? — is not overly complicated. Romeo consistently made the “right” decision over the “easy” decision. In life. In football. In relationships. He uses Josh Gordon as an example. How easily we forget the ex-Browns receiver blowing up for an NFL-high 1,646 receiving yards in 2013. “Josh Gordon,” he adds, “was that dude.” Gordon, however, was suspended multiple times for substance abuse.

Growing up, Doubs saw an endless number of lemmings give in to temptation. Never to be heard from again.

“Making a bad decision is a lot easier than making a good decision,” Doubs says. “If somebody says ‘good decisions are easy to make,’ I’m going to take that as a lie.”

That’s why Doubs has zero problem cutting people out of his life. Most recently, he stopped talking to one of his best friends who was like family. This wasn’t bad blood, rather a “business decision.” He doesn’t divulge many details but, judging by the way he glances over at his girlfriend, this was an emotional split. The longtime friend was deemed a negative influence. No heart-to-heart conversation was needed. Rather, as Doubs ascended, the two naturally veered off into separate lives. His two hands split opposite directions over the table.

Reliving “What ifs” and gang life and forgotten friends obviously is not fun dinner conversation.

One word, however, completely brightens his mood: Football.

For the first time, Doubs cracks a huge smile.

“Football, man… What it’s done for me, it took me away from stuff I would’ve never thought I would’ve got to. It took me away from a lot. A lot, bro. I don’t even know how to put it into words at this point. What it has done for me? I’m speechless.”

He was not always this humble. Romeo Doubs pinpoints the moment he needed to check himself. Back in high school, he wasn’t invited to a summer football camp. Another kid was invited to this camp, received college offers, and this kid — in his mind — couldn’t hold his jockstrap.

“My arrogance at the time,” Doubs says. “My first thought was, ‘Oh, I’m better than this dude.’ Even after the fact, thinking about it now, it’s just like, ‘Who are you to say you better than somebody? When you didn’t even put yourself in position. Secondly, you were lazy.’ You think you have it figured out.”

From Jefferson High School to Nevada to the pros, Doubs learned to embrace “the beauty” of the sport’s struggle. He can relate to the story of Damar Hamlin, the Buffalo Bills safety who estimates that more than half of the kids he grew up with in McKees Rocks are dead. When we sat down in Buffalo, just like this, Hamlin insisted he wanted to give kids in his neighborhood a beam of hope. He then nearly died on a football field, became an inspiration worldwide and strapped on the pads again. He achieved his mission.

This is how we reconcile our support of a dangerous game.

Football is forever an outlet for teens teetering on that edge of “three times… five times…seven times.”

A reason to say “no” to fast money and pursue a college scholarship.

Yet, Doubs makes a critical distinction. Football only serves as that escape if you’re willing to make hard decisions. And every game, every practice, every workout presents you with those hard decisions. With its inherent physicality, this sport is unlike any in the country. Get smacked in a hitting drill and you’re more than welcomed to leave. There’s the door. There’s the street corner. It’s on you to stick with this as the alternative. The mentality it takes to play this sport, Doubs says, is “draining.” Back in high school, he’d quit workouts if things didn’t go his way. Twenty minutes later, he’d put his cleats back on, and resume.

Crying through workouts. Angry through workouts. Happy through workouts. Eventually, he got 13 offers of his own. Of course, Doubs chose Nevada because Mom didn’t give him any other choice. This was a quick, direct flight from LA.

Even in college, he considered quitting. His first fall camp, glove-less, he couldn’t stop dropping the ball. It was hot. He was cussed out every day. Conditioning each summer was always brutal, too. Strength coach Jordon Simmons, a former member of the United States 3rd Group Special Forces in Fort Bragg, N.C., would run players “to death,” he says. But he never quit. He bought into everything and matured into one of the best wide receivers in the Mountain West Conference under the mentorship of Eric Scott. Mom might’ve forced his hand, but Nevada proved to be the best landing spot for Doubs because Scott was an L.A. native himself. Scott coached a team Doubs played in high school.

He could relate. He knew which buttons to push.

“He played a part in this football journey,” Doubs says, “just as much as my brother did.”

Doubs improved each of his four years, finishing with 3,322 yards and 26 touchdowns on 225 receptions.

He only concerned himself with the task that given day. Nothing more.

“That’s why I preach on progression so much,” Doubs says. “Progression isn’t really seen often. Progression is more of the ‘Ah, okay…’ Kind of just brush it off. Up until someone gets in their final moment and then you start to do the research on him and then you start to see like, ‘Oh, I didn't know he did so and so.’”

He cites Kobe Bryant as an example. Everyone sees the five titles, the 18 All-Star appearances, the 81-point game, the killer instinct on the court. Few remember how his career began. Bryant didn’t even start his first two seasons. As a rookie, he famously ended the season with four airballs in the fourth quarter and OT against the Utah Jazz in the Western Conference Finals. But he learned from that moment. After studying the film, Bryant saw that each shot was on line but fell short because his legs were so weak. Physically, he wasn’t prepared to leap from 35 games max in high school to 80 that rookie season. That offseason, he completely changed his weightlifting program.

Doubs attacked his own weaknesses throughout college and the four years shaped him.

On to the NFL, he was in good hands. Former No. 1 overall pick Keyshawn Johnson became a mentor and knew exactly what Doubs needed to excel at the next level: Terry Robiskie. An NFL coach from 1982 to 2020, Robiskie gained a reputation as one of the best wide receiver coaches in the league. His workouts? Legendary.

Robiskie has never told Johnson “no,” and vice versa.

So, ahead of the 2022 NFL Draft, Johnson called with a favor.

“Work his ass until his tongue’s hanging out of his mouth,” Johnson told Robiskie. “Don’t give him one inch because he has all the potential in the world to be The Guy.”

10-4.

Keyshawn had Robiskie’s word.

Those NFL scouts chatting with a sick-as-hell Doubs never learned the Real Romeo, but the Green Bay Packers certainly did.

II: ‘Perspective Game’

The goal was simple. Push Romeo Doubs to the brink of mental destruction.

Here was Terry Robiskie’s recollection of his conversation with the wide receiver’s mentor, Keyshawn Johnson:

“Kill him if you have to. Make him be the best he can be. Get him ready for the draft, and then get him ready for what's coming after.”

Music to the coach’s ears. This has been his specialty since the 1980s. Before they’d even hit the field, the mind games began. Robiskie would tell Doubs to meet him at one location in Los Angeles and then — two hours prior — switch it up to a different location. Robiskie wanted the kid to be adaptable, to always be ready for What’s next? They might’ve been planning on getting work in at a high school, then… boom. Robiskie tells Doubs to swing over to UCLA’s facility instead.

In the NFL, he told him, you’ve got to be a “lizard” changing colors on that tree.

Doubs didn’t flinch. A good sign.

From there, any given day, “Camp Robiskie” could last five, six, seven hours long.

A sampling:

Workouts that’d last 2 ½ to three hours.

X ‘n O talk for an hour-plus.

Another hour of drills/routes. Perhaps third-down or red-zone work.

Foot speed drills. Blocking drills. More catching drills. This could last another two hours.

And, always, Robiskie worked in deep conversations on how this whole NFL thing really works.

Never once did Doubs express verbally or in body language that he was tired.

“No matter what I fed him, he never got tired,” Robiskie says. “The more I kept pushing him, the more he kept going. There wasn’t one time I pushed him, he ever pushed back.”

Occasionally, high school kids would jump into the drill to give Doubs a blow. His quarterback? Jarmaine Doubs Jr. Not every throw’s going to be pristine in the pros. Robiskie saw true value in “ManMan” serving as the all-time QB. Passes were high, low and, no, Romeo would never even think about complaining to his best friend. When Romeo’s mother and sister watched on, Robiskie would point their direction. “Maybe you’re tired, but you see those people over on the sideline? All that shit they’ve been through in their lifetime, they’re tired too,” he told him. “They’re counting on you to help them get a better life.” He recited to Doubs exactly what he told Roddy White, Julio Jones, Kevin Johnson, Tim Brown, James Lofton, all of his receivers over his four decades: “Listen good and do what I tell you and you’ll make more money than you've ever dreamt you could have made in your life.”

This was quickly followed with more advice: Don’t buy a damn Mercedes Benz with that first contract.

When Doubs headed to Carlsbad, Calif., Robiskie made the 100-mile drive south and back 3 to 4 times each week. Whenever Doubs was finished throwing weights around, they’d hit the field for two hours and then return to the hotel for board work. Robiskie drew up X’s and O’s: This is how you beat that coverage. This is how you beat that front.

This old-school coach didn’t put up BS. Doubs learned that much during Senior Bowl Week. Robiskie couldn’t make the trip to Mobile, Ala., but told Jarmaine to record all of Doubs’ 1-on-1 work. That way, he could critique from afar. When the footage was forwarded, he was mortified. Right there on the screen — before a 1-on-1 rep — Doubs reached across the line to shake the defensive back’s hand.

Robiskie lost his mind.

He immediately called Jarmaine.

“Run out there to the fence by the sideline,” Robiskie told him, “and you tell MF’er I said, ‘Don't you ever in your goddamn life shake hands with the enemy across from you!’ You tell that son of a bitch he’s down here to get a job and he’s down here to make money. He ain’t here to make no g--damn friends. If you want to make friends, you should stay in LA and sit up on the corner of Crenshaw. ‘Don’t ever shake a g--damn hand again. Unless it’s you’re first cousin, don’t ever shake a hand again. And don’t let me see it.’”

The message was relayed. That night, Romeo called Robiskie.

He made no excuses. He didn’t shake any more hands that week.

When he wasn’t running routes for Robiskie, Doubs trained with Roy Holmes Jr. of AMP Performance. A man who had the same first impression as everybody else: “This kid is super, super quiet.” Holmes started calling Doubs “Franklin Saint,” from the TV show Snowfall and was able to crack this hard shell over time. Doubs must trust you before he opens up and that’s a problem for NFL teams. Too many prospects and too little time, Holmes explains, to truly get to know such a unique personality. A few skeptical scouts even grilled him for information, citing the fact that Doubs was so reserved in their interviews. Holmes told them he’s a kid who’ll clock in and work like crazy without saying a word. You’ll hardly know he’s there.

He likens Doubs’ approach to Barry Sanders and Tim Duncan. Too often, he believes, we want to put players into the same box because it makes us feel comfortable.

“That’s the beauty of him,” Holmes says. “He’s different and he’s so humble.”

Doubs got into the habit of saying “1 percent” to Holmes and walking on by. That was his goal. Stack 1 percents over their eight weeks together and see where he lands.

“In the world of NIL, me, me, me, all the stuff like that, he’s completely different,” Holmes says. “He’s not a receiver diva at all. He’s got Mike Evans in him where every year he’s consistently putting up yards, putting up stats, but he’s not one of those guys that gets a lot of the respect because he’s not super flashy. A lot of teams coming out in the draft process were taken back by that: How are you this talented but you don’t really say much?”

At his core, Doubs was ultra-competitive. He’d constantly ask for work — more 40 starts, more bench press. His raw explosion was jarring out of a stance. And, inside the weight room, Holmes describes a “Jim Brown mentality.” The ex-Browns fullback refused to let defenders think they ever hurt him on the field, and that was Doubs. He barely grimaced or grunted at all pushing up weight.

The only times Holmes knew this was a hard workout for Doubs was if the receiver gave him a subtle nod of the head.

“He’s never one of those guys who’s going to drop down to a knee and just be defeated,” says Holmes, “and he was never going to let you know that you were winning.”

Ah, yes. Robiskie has broken receivers before. It’s his thing. Doubs’ stone-cold reaction — to everything — reminded him of another player he worked out in ‘96. On the drive to Tennessee-Chattanooga, tired as hell, miserable, Robiskie decided to work a wide receiver until he literally puked. That was the objective: Breakfast on the field. A funny thing happened, though. As the QB himself, Robiskie threw… and threw… and threw… to the point of his own arm getting sore. He’s the one who needed a water break. Three hours in, this specimen of a receiver asked Robiskie how long he planned on working him out.

“Why?” asked Robiskie. “You getting tired?”

“No,” the player answered. “But I do have a basketball game in a couple hours.”

The player was Terrell Owens.

Recalls Robiskie: “Holy shit. I was trying to kill him.”

That night, Owens didn’t look tired at all on the hardwood for Tennessee-Chattanooga. When he got back to Washington, Robiskie told everyone in a Redskins draft meeting that Owens was a late-first, early-second round pick and was laughed away. At No. 30 overall, Washington went on to draft offensive tackle Andre Johnson out of Penn State. He never played a game for the Redskins.

Owens fell to the 89th pick in the third round. He’s in the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

This time? An NFL team listened to Robiskie. One connection sure helped.

Back when he first entered the coaching ranks as the Los Angeles Raiders special teams assistant, ’82 to ’84, Robiskie helped convince the team to draft a speedy running back out of tiny Western State College (Col.) named Sammy Seale in the eighth round. Then, he pushed even harder for Seale to make the team as a nickel corner and special-teamer. Seale, all guts, lasted a full decade in the NFL as player. Today, he’s a national scout for the Green Bay Packers.

Naturally, Seale called Robiskie to ask about Doubs ahead of the 2022 NFL Draft.

Robiskie didn’t hold back.

“He’s got your determination,” Robiskie told Seale. “He’s got your heart. He’s got your fight. He’s got your desire. He’s got your will to make somebody’s team and to make them better. And he's really, really deep-rooted in his belief in being a good football player and making a team the same way you were.”

Other teams failed to understand Romeo Doubs. Not the Packers.

After selecting Christian Watson in the second round, they took the Nevada wideout in the fourth.

Meanwhile, the work with Robiskie did not end.

After OTAs and minicamp, Doubs called the coach up. “When we working?” he asked. “Tomorrow,” Robiskie answered. And into July — the one chance all NFL players have to catch their breath — Doubs begged for more. He asked Robiskie to train again and Robiskie said he was heading to Denver to visit his sister. No problem. Doubs’ former head coach at Nevada was now the head man at Colorado State. Nobody was on the premises over this July Fourth holiday but Jay Norvell gave Doubs the passcode to the facility.

Two footballs in tow, Robiskie made the 65-mile drive to campus for three separate workouts.

After picking up Doubs, the two noticed a spot off the highway where a car had apparently skidded into a ditch. The scene was vacant, but Robiskie did eye some police caution tape left behind. So, he pulled off the road, rolled the tape up and brought it to the field with them. For the first 2 ½ hours that day, Robiskie set the footballs aside and ripped Doubs through drills off that tape alone. “Routes… on routes… on routes… on routes,” Robiskie says. They climbed up the route tree. They ripped through more red-zone work. Robiskie taught Doubs how to play stronger from the 20-, 10- and 5-yard line in because that’s where everything gets compact. It’s no coincidence that Doubs has emerged as one of the best red-zone targets in the NFL.

Toe-dragging drills. Robiskie instructed Doubs to wear black shoes so the officials will always eye the difference along the boundary. Blocking drills. Robiskie had Doubs cutting blocking dummies they found in Colorado State’s equipment room. One-handed catches. Robiskie loathes those who try catching the ball with one hand on purpose. But he knows there’s always a chance the DB will hold a receiver’s arm back.

Robiskie also showed Doubs how to push off a DB with his shoulders — not his hands — so he gets separation without being penalized. Such nuance is a game-changer.

The final conversation the two had in-person was most important. Robiskie never coached in Green Bay, but calls former Packers GM Ron Wolf one of his best friends from their time together with the Raiders. He knew what awaited Doubs. He told the kid to eliminate all dreams of $50,000 Rolexes and fancy cars and gold necklaces and to buy a damn pickup truck for the winter. “When black people move to Green Bay,” Robiskie began, “they’re moving to Green Bay to win a Super Bowl. That’s the only reason black people go to Green Bay.” Next came a history lesson. Inside this booster club room — not a soul in sight through the glass window — Robiskie drove home one final message.

Up the board, he started writing the names of Packers receivers: John Jefferson, James Lofton, Sterling Sharpe, Donald Driver, Greg Jennings, Jordy Nelson. He worked out Nelson, the farmhand from Kansas State. People again looked at him like he was nuts for saying Nelson should be a first-rounder. Lastly, he brought up James Jones because this was another west coast kid with a big body who caught everything. Robiskie told Doubs that Jones was once considered too slow for the NFL but left as one of the Packers’ best receivers.

His point: You landed in the perfect spot. You have the talent to join this list. At one point, he also pointed out that the NFL’s first true star at wide receiver played for the Packers. If Don Hutson was able to perform in 12-below, there’s no reason he can’t.

Romeo Doubs, he finished, needed to go in thinking: I’m going to be the best on this roster.

Doubs didn’t say a word. Hardly blinked. That was typically his reaction to everything.

“I could go over things with him and sometimes I have to ask him: ‘You listening to me, you hear what I said?’” Robiskie says. “And he didn’t react to nothing at all. But he always had it. He got it. It was on his mind. He heard what I said and he knew it.”

Doubs is on track. His Year 1 and Year 2 numbers mirror Jones, and he’s done it with the Packers transitioning from an aging great to a quarterback making his first starts.

Robiskie cannot help himself. He still shoots Doubs texts during games. After the wideout caught a ball between two DBs on a corner route, he wrote: “You’re doing what you’re supposed to do. I love it.” After Love threw an interception and Doubs stopped running, he didn’t bother thumbing through a text message — Robiskie left a voicemail. MF’ed him. Told him that kind of laziness embarrasses Love. Demanded Doubs chase down that DB “and take him to the g--damn ground. Don’t you ever stand up and watch a DB do that again as long as you live. Don’t ever do it.”

Doubs called him back to assure the message was received.

But here’s the thing. Doubs hasn’t had many opportunities to chase down a defensive back.

Love has thrown one interception on his last 300 pass attempts.

This offense is exceeding the wildest of expectations.

Youth was the CODE RED concern. The entire Packers wide receiver room wasn’t even born when the team drafted Driver. They’re all 24 years or younger. All offseason, all September, all October, riiiight up to mid-November, the wideouts were universally belittled as a position of weakness.

The dearth of experience, it appeared, was stunting Jordan Love’s development.

This theory was then cannon-blasted into the arctic sky. Green Bay is two wins from the Super Bowl. This starting quarterback doesn’t ice out receivers or force-feed anyone specifically.

“Everybody can play in our room,” Doubs says. “Not even bragging about it. At some point, that was the question: ‘Oh man, can this guy Jordan play? Can these receivers do something? Dude, everybody in the NFL is going to have their slumps. They’re going to have the best of times, the worst of times.

“Everyone’s getting involved. Everybody can ball.”

Brian Gutekunst’s gamble as GM was that his handpicked QB would genuinely grow with young receivers from the ground up. Growing pains were real, but something clicked from Thanksgiving on. All the reps receivers got in with Love during the offseason started paying off. Doubs took his maniacal training mindset from Robiskie in ’22 to Love in ’23. Nobody has caught more passes from the QB than him. Both are Cali Cool. Both played in the Mountain West. Given their laser-beam, flat-line demeanors, it’s no shock they hit it off over endless offseason work together.

Doubs repeats it several times: All of his reps have come with Love.

He won’t discuss his own game, but he’ll sure praise his QB.

“Jordan, his poise is insane,” says Doubs. “And I talk to him all the time. He can have a bad play and his mouth is closed. I’m not saying he’s a robot. Obviously, if he makes a mistake, he’s going to talk through what he did wrong and then learn from it. But even if he makes the best of plays, he’s still on the iPad.

“His consistency is through the roof man. To witness it, it’s amazing.”

After Aaron Rodgers, this brand of leadership must be a breath of fresh air. Love, the same age as the playmakers all around him, doesn’t get too high or too low. Rodgers had a very specific “standard,” Doubs explains, and fully expected everyone to meet that standard. That’s not a knock. He enjoyed their time together, too. But what this crew clearly needed was patience. A full 2 ½ months within Matt LaFleur’s offense. Not Rodgers’ improvisational interpretation. Now? This unit is humming. Against the Vikings, Bo Melton (6-101-1) stepped up. Against the Bears, it was Dontayvion Wicks (6-61-2). In the playoff blowout over the Cowboys, Doubs went off.

Again, Doubs is not one to manifest. He never closes his eyes and envisions himself utterly dominating cornerbacks. That’s what gives Robiskie pause, too. Deep down in his heart, he isn’t sure Doubs has the confidence to be Sharpe or Lofton or Davante Adams. If those receivers are 10s, he calls Doubs an 8.5 because he’s not sure the receiver has the confidence to say point-blank, “I’m going to the Hall of Fame.”

“I think he’s just playing the game to catch a lot of balls, to help the Packers win,” Robiskie says. “I don’t think he goes out on Sunday to dominate that guy across from the line.”

He brings up the Senior Bowl handshake.

“That other group of guys I just called for you, they ain’t shaking nobody’s hand,” Robiskie says. “They’re kicking people’s ass. I don’t care if it was Deion Sanders or Rod Woodson, Charles Woodson. They’re going to beat his ass in the ground. And they’re going to put a dagger in your heart. James Lofton would put a dagger in your heart. Davante Adams today is still putting the fear of God in people. I think that Romeo Doubs goes out there with a mindset of ‘I’m going to bust my ass. I’m going to do what I got to do today to help my team win the game.’ I don’t think he’ll go the game and say, ‘I’m going to catch 11 for 192 and two touchdowns. I’m going to destroy this boy.’ He takes his time and he lets the game come to him.”

He is not sure Doubs ever can ever get this mindset, too, saying he’ll humbly catch his slant, his comeback route and would rather pluck a fade route over a DB’s head from the 10-yard line than embarrass a corner on a post for 80 yards.

Maybe Robiskie’s correct, and Doubs lacks the malice to make defenders pee down their leg. But the man who brought these two together, Keyshawn Johnson, finished with 10,571 career receiving yards in his own career by bringing such malice to the playing field. And he believes. No, Doubs did not author his own “Just Give Me The Damn Ball!” tell-all as a rookie. Johnson used to inform cornerbacks straight-up they’re about to be on SportsCenter, make a play and shout, “I warned you!” That’s not Doubs’ personality, but he sees a quiet fight in his mentee and points to other receivers wired the same way: Marvin Harrison, Eric Moulds, Tyler Lockett.

Johnson grew up in L.A. himself. He knows everything that fueled Doubs to this point.

“I always think that the best football players are the ones that have been through some stuff,” Johnson says. “That’s been my motto for years: ‘That dude can play, man. That dude has been through some stuff.’ You don't have to be from South Central. You can be from a little old country town somewhere and just go through the grind and the heartache and pain of not knowing where your next meal might come from. Those are always the guys I want. I want those guys. Because those are guys I can rely on.

“We grew up in the same area. It’s from knowing — been there, done that.”

If the Packers do start feeding Doubs the ball 10 times a game, Johnson sees multiple Pro Bowls in his future. Holmes, too. He trained Brandin Cooks, Julian Edelman and sees “generational” potential in Doubs. His comparison? Ex-Jaguar Jimmy Smith. His only hope is that people do not misconstrue silence for complacency. To him, there’s beauty to such a talented wide receiver not pounding his chest.

Robiskie might’ve been telling Doubs to look at his mother on the sideline and imagine a better life for her one day. But even back to middle school, Doubs never once said that he wanted to get to the NFL “to change my family’s life.” That’s not a motivator. He repeats, again, that he’s literally taken life one… day… at… a… time. Fans, trainers, coaches, media. Doubs admits this isn’t what people want to hear.

Forget Canton proclamations.

Asked broadly where he sees his life heading, Doubs has no answer.

“Some may say you’ve got to manifest it,” Doubs says. “Yeah, I get that. But sometimes that’s just the way how life is. You can sit here and say you want something and ultimately you don’t get that? That’s where the struggle starts. I’m a completely different guy when it comes to stuff like this. You’ve just got to let it come. Whenever the time is right, the time is right. I can’t sit here and say, ‘I want to be this All-Pro guy.’ And I get it: As an athlete, that’s the mindset. You want to be the best ever. But that’s not who I’ve been. I have to stay true to that. And people lose that at some point in their lifelong journey.”

He’s dead-on correct, too. Fame changes an endless number of athletes. People may view him as “quiet,” he says. “Square’ish.” That’s fine. Doubs refuses to become somebody he’s not.

The man he is — a man living in the now — is doing pretty damn well.

He cares most about the two ladies at his side. Doubs gained an entirely new appreciation for women during Andrea’s pregnancy. He didn’t know what to do when she was in pain. But he tried his best. When their infant baby cried through three long months of colic and doctors had no answers? They got through it, together, one day at a time. He’s very close to his mother and speaks to his father every once in a while. His Dad found a job and, Doubs says he’s doing “solid.” Obviously, his success has lured South Central peers out of the woodworks. Names he’s never heard before. He’s got no problem ignoring texts from those claiming to be his pal back in the day. And if people need him, they know to go through Jarmaine Jr.

This playoff run is foreign terrain — his spotlight will only brighten — but he genuinely does not care.

The concept of “legacy” means nothing to Doubs. He’ll never be the ex-pro reliving old war stories to an adoring audience.

“Not saying there’s something wrong with that,” Doubs says. “But I’m just talking from the shape of who I am. I had the spotlight in high school. I didn’t give a f--k about that. I had that shit in college. I did not care about that. So having it here, the only thing I can be appreciative for is the fan base. Especially with it being owned by the fan base. But forget the spotlight, man. And even if I do want it? It ain’t time yet. In my eyes, it's not time yet.”

Doubs promises he’ll never look too far ahead.

His focus will not blur.

“I’m telling you, man. The perspective game? It’ll take you places.”

He looks at his daughter.

“I need to teach her, man. I need to teach her the perspective.”

One day, he’ll lift up his head and appreciate what this day-to-day patience has provided. He’ll realize his rise convinced kids in South Central not to hang with that gang the first time, let alone a third or fifth. They’ll envision a different future before it’s too late and lock into the present. He’ll share this perspective. Maybe Robiskie or another trainer even uses the name “Romeo Doubs” in the same breath as those Packer greats with a future draft pick.

There’s a chance he’ll even look back at this 2023- ’24 season as something special.

For now? Doubs is perfectly content catching that 10-yard slant route from Love for a first down, finishing a nice meal with his family and bundling up his daughter in her pink coat for the winter chill.

There’s no reason to think beyond tonight.

I don't have the time today to read this but ita on deck. Im glad i found this substack; BEFORE the McDermott 9/11 thing. Yesterday I curiously went digging for the old aaron rodgers original expose of many years back; players who didn't like him, since it made me learn who he really was before he went full blown anti vax diva. The author who was pilloried by rodgers and packers nation? Tyler Dunne.

Tyler... this is a great stuff. I coach baseball. If it’s okay, I’d like to share some of this with the guys. Awesome stuff.

Young men underestimate the grind. NO ONE wants to get up and put in the work, right away. I have a kid, he is grumpy at the start of every workout. But when the work is done... he’s on cloud nine. This is the lesson guys need to learn. And that Doubs had so much “quit” surrounding him, and didn’t. Awesome. You and also tell he’s a really sharp young man. Love this!