'Pain is glory:' DeVier Posey is the true football journey

This sport took the former OSU star all over the US and Canada. It dragged his name through the muck, it tore his Achilles... and he also gained more life lessons than he ever would've as an All-Pro.

We all lionize the sport’s greatest stars. Fans. Media. Players.

Which is fine. The big names draw the most interest.

And yet, too often, throwing on Sportscenter or binging NFL RedZone fails to help us understand the true life of a pro football player. It’s the Instagram effect. Projecting the highlights of one’s life is status quo. For everyone. Nobody’s going to publicly broadcast their lowest of lows for thousands of followers, so nobody gets an authentic depiction of day-to-day life in America from their own friends. Football’s no different.

Well, there’s an underbelly to the NFL that we try to reveal here at Go Long, however possible, from Ryan Leaf to Jerry’s World to the new Minnesota Vikings.

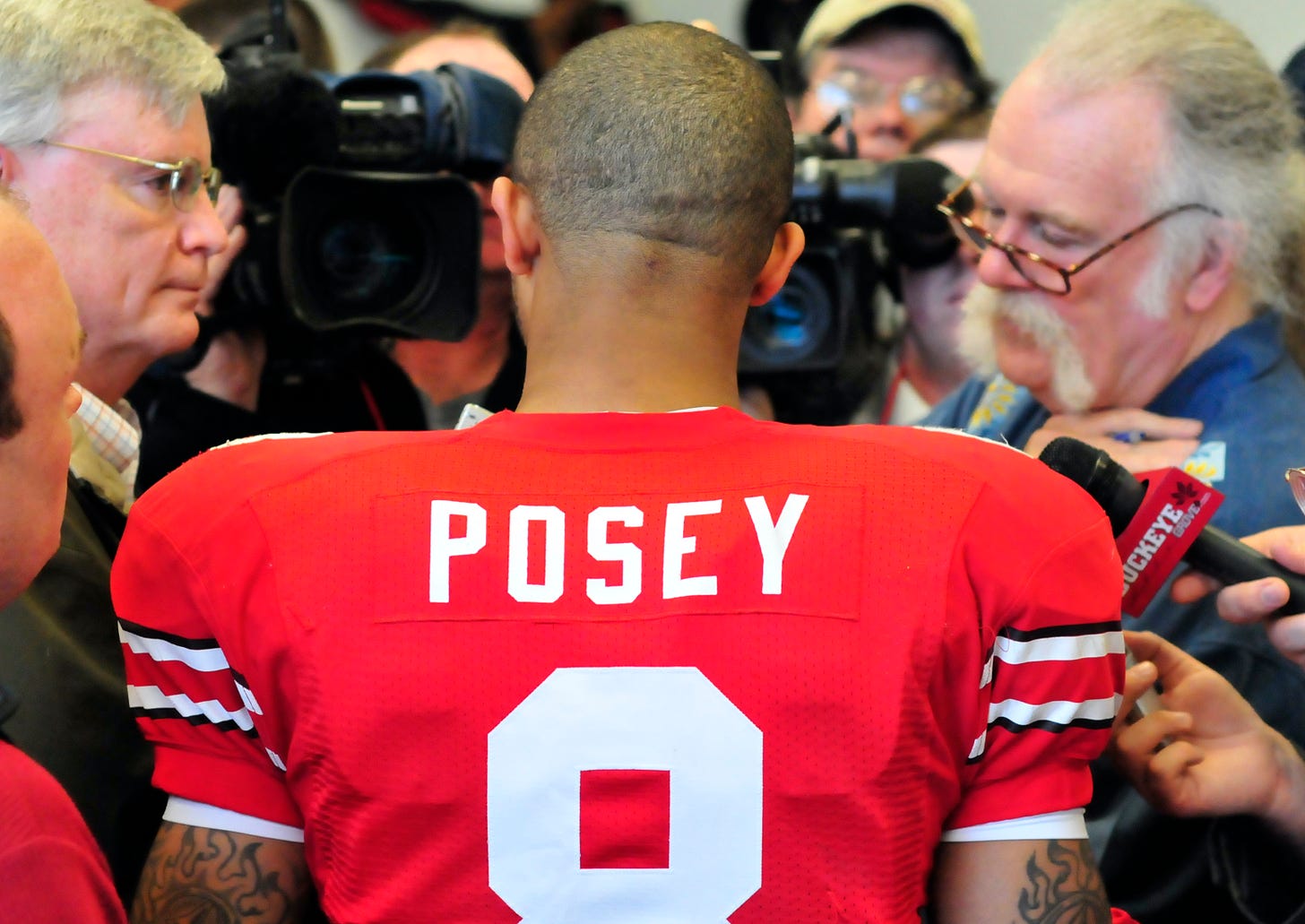

Recently, I connected with a former player whose name may or may not ring a bell: wide receiver DeVier Posey. He starred at Ohio State, catching 113 balls for 1,676 yards with 15 touchdowns in 2009 and 2010. He was then one of the Buckeyes embroiled in controversy for selling memorabilia to a tattoo artist. (The silliest of scandals, in retrospect.) Posey was drafted in the third round by the Houston Texans and embarked on a football odyssey that spanned North America, from the Texans (2012- ‘14) to the New York Jets (2015) to the Denver Broncos (2015) to the CFL’s Toronto Argonauts (2016- ‘17), back to the NFL’s Baltimore Ravens (2018), back to the CFL’s BC Lions (2018), Montreal Alouettes (2019), Hamilton Tiger-Cats (2020- ‘21) and BC Lions (2021). He’s finally done playing, but this father of three is only getting started in life.

For our latest Q&A conversation, I figured we’d explore genuine NFL (and CFL) life.

Back when he was tearing up Big Ten defenses, no way did Posey expect to move his young family “eight to nine times.” But, he did. And he’s thankful for everything. There were rough moments — the Ohio State drama sent him into depression and he suffered some brutal injuries as a pro. Late in a playoff loss to the Patriots, Posey once tore his Achilles… and it felt like somebody shot him from the stands. Yet, Posey was also named the Grey Cup MVP in 2017 with Toronto, helped his wife give birth to a child in an apartment and knows he learned more than he ever would’ve as a perennial Pro Bowler.

“I’m rich in relationships and rich in experiences,” Posey begins. “I love how my journey played out, man.”

Everyone in college football making millions on NIL deals should probably thank Posey. He opens up on what went down in Columbus, too.

Here’s our full conversation. Thanks, all.

Join the Go Long community today by becoming a subscriber. Free and pay options are both available, and you can always gift a subscription to a loved one this Christmas season:

What’s your life like? This is your first year not playing, right?

Posey: This November, I’m going into Year 2 of not playing. I moved back to Columbus in the pandemic. In 2020, the CFL shut down. We got a big severance pay. It showed me there’s more to life. I had a newborn at the time. He was born in ’19. I had my son. He was about six. He was about to start school. You’re with your family. You start re-doing things. I started coming up with business ideas and things I wanted to do in my next phase of life. I had an overwhelming spirit of entrepreneurship, overwhelming ideas that I felt would serve to my future. I just felt like football served my kid dreams. I don’t know if you ever read, “The Fifth Agreement” by Don Jose Ruiz. It’s a great book. The first book is the “Four Agreements.” And the second one is just not taking things personal. In the book, it talks about the dream of the first attention, and how you were the dreamer who dreamed the dream. But your life purpose comes from the dream of the second attention. That just hit me. When you think about a lot of athletes, that’s their first dream. That’s the first thing they ever want to do: Be an athlete. Get drafted. Make a million dollars. Buy a car and a house. I started realizing my life purpose was my dream of my second attention. Your calling is sometimes bigger than you. It’ll devour you. I felt like it was time to attack that second dream, and I had to give up my first dream.

But what the first dream teaches you are the tools you’ll have for your calling. So just having those bouts of adversity. Being able to plant my feet and be myself in any city or state and go out and play taught me I can manifest anything that I want. I can create relationships out of thin air because that’s what I did with past teammates.

So, I have a nonprofit. I’ve had it since 2013. Starting to expand that. I have a logistics company. We do flatbed concrete. And believe it or not, I’m building a health-tech platform that I think by 2025 will be up and running and helping a lot of people take the health back into their hands and give them the right tools to take care of themselves and be able to connect with the right people outside of normal and traditional medicine. I was pretty good with my money so I get to stay home and take care of my kids and be their coach. I try to maximize each day, not max myself out and just take care of my spiritual and mental health. Football takes your body but it can’t have my mind. My mind is a powerful thing so I try to put that to use and put it to work and live this dream of the second attention.

How is your body after a life in football, playing receiver, taking the hits you did?

Posey: Oh man. It’s f--ked. It’s terrible. Waking up with pain every day. But it’s something you look at and you realize: “Would I do it all over again? Hell yeah.” Just to learn what I learned. You learn so many things. I had a lot of injuries, but it was all worth it.

What hurts the most right now?

Posey: My back. My neck. My shoulders. My hands hurt in the cold. But that’s what football is. It’s a brutal sport. You put your body on the line. That’s why I respect these guys who go out there each week and play. They’re gladiators. Modern-day gladiators. It’s a blessing, but at the same time, you learn to take care of yourself.

Was there a hit that still sends a chill up your spine when you think of it?

Posey: I’ve had those brutal hits. My first time in the CFL, my first game, Ricky Ray — a legendary Canadian quarterback, he’s basically the Tom Brady of the CFL, he’s the only quarterback to win four championships up there, he went to Sacramento State and was a big CFL guy — he threw a pass behind me. I looked back and this guy named Glenn Love, man, he caught me right under the chin and knocked me out. By the grace of God, well, not by the grace of God, those concussion tests are pretty easy to pass. So I ended up still playing that game. And one time I was going across the middle and a guy speared me in my back. I finished the game but I still felt it. And probably the last hit that ended it, I caught a crossing route in Montreal. As soon as I got down, somebody hit me right where your upper thigh and groin meet. It was a thigh bruise that was so bad I thought I’d have to get one of those corset stitches where they split it open just to release it. A guy looked out for me and got the swelling down and I was able to walk and play again. I tried to play one more season on it, but it never went away.

That doesn’t sound like a place I want to get hit.

Posey: Have you ever rolled out on a foam roller? It’s that spot right by your hip. That ball that’s always tight on every human. It’s right there. Sometimes, it still hurts.

Your football life. Your journey. Where does it start?

Posey: I came here a Make-a-Wish kid back when I was born. I was born in San Francisco with half of my immune system. So, I was born with less white blood cells. Essentially what that means is, I’ve never had a fever in my life. I would just get sick. What a fever is, technically, it’s your body heating up the sickness. I never got those signs so my meter is always off. During Covid, it’s funny, I told people it’s going to be 97.3 everywhere I go. You have to get your temperature at every location. My Mom petitioned the state of California. I was able to get IVs and gamma globulin shots, and she did it through the Make-a-Wish foundation. That’s part of the reason I always wanted a nonprofit because a nonprofit helped pay for my care and impacted me as a kid. So once we moved from Cali to Ohio, I was raised by a single Mom. I was one of those kids who gravitated toward football.

I started playing football in kindergarten and was always a natural. It was always tough because of how physical it was and the conditioning. So I kind of started hating it. And then when I got to school, I wanted to play quarterback. When I got to high school, I went to one of those all-white Catholic schools and my class was one of the first classes with a bunch of African-American dudes who came in. So I ended up losing the job. They said, “You should try receiver.” And I said, “Man, I quit. I don’t want to play.” I was a hooper. I played varsity basketball as a freshman and was a sophomore starter, so I figured basketball was my game. I didn’t play varsity football until my junior year. And I just exploded, man. All-State. The rest is history.

I think I’m the only wide receiver in the history of Ohio State — in their great wide receiver history — to score on their first catch. I was like, “This college stuff won’t be too hard.” Sophomore year, I was a starter. Going into my junior year, Coach Tressel knocks on my door. He asked me and Terrelle Pryor to come talk to him. He says, “We found out you sold your stuff to a guy who’s getting indicted.” Let’s ball out and let’s leave. That year, we were 12-1. We lost to Wisconsin. We were No. 1 in the country and ended up out of the national championship picture. After the Michigan game, the sanctions came down. Some people didn’t want us to play in the (Sugar Bowl). Some people wanted us to play in the game. It was clear it was about money: the NCAA wanted us to play. We ended up playing. There was a lot of stress that went into it. All five guys who got in trouble all impacted the Sugar Bowl. We beat Ryan Mallett and the Arkansas Razorbacks. And then we were confronted with, “Do we go into the draft? Do we stay?” Coach Tressel made us sign a contract and asked us to stay. We stayed. I fought through it. I really wanted to graduate at Ohio State and learned how to walk through adversity on campus. All these Twitter trolls. Twitter was just coming out. I was learning social media stress. Me and my wife got close. My Mom helped me with the NCAA investigation. I had to go through an audit in college. The NCAA requested all this crazy information. Through the audit and through the appeal, I had to serve 10 games my senior year. So I went from, not a God, but people praise you around Columbus when you’re a starting wide receiver or a quarterback, a running back or the left tackle. So when that hit me, I thought my dreams of playing in the NFL were over.

Went to the Combine, ran a great time. I talked to a bunch of NFL guys and I ended up getting drafted in the third round after only playing three games my senior year. After that, I was starting around November, December and it was looking like I’d have a breakout year my second year. We’re playing the Patriots in New England. I tear my Achilles in the fourth quarter. We’re getting smacked by Tom Brady — this was the Aaron Hernandez, Gronk, Shane Vereen team. They were absolutely ridiculous. The time it happened in the game, it was so unnecessary. I was like, “Why? Why is this happening?” So, I had to battle adversity again. Then, we drafted DeAndre Hopkins. They asked me to tutor him, to mentor him, to sort of take my spot. Me and Hop became great friends and we’re still good friends to this day.

After that, Bill O’Brien came in. We didn’t see eye to eye. He traded me from Houston in ’15. Got to the Jets. I got married that year and had just bought a house in Houston so it was like, “Wow. This is the worst time to get uprooted.” I battled more injuries. I think they were stress-related. I got cut. I was out of the league a long time. I worked out for six teams in ’15. I got signed to Denver. Gary Kubiak was the offensive coordinator out there — I signed a futures deal in December and then that January the Broncos ran the table and won the Super Bowl. So I was like, “That’s not a good idea. They’re not going to change anything about that room.” I was in a training camp battle and told myself I worked so hard to come back from this injury and did so much under-the-surface work that I just want to play. My brother was playing in Canada so I drove to Toronto, saw him play and was like, “Man, I can play this game. This is a real professional league.” They’ve got fans, their own game, a lingo when it comes to football that’s different. I’m going to go to the CFL and my whole goal was to ball out and make it back to the league. I got cut from Denver. I went home for three to four weeks and I wanted to make sure my wife wouldn’t leave me because I was going to go to a lesser league and making way less money. I wanted her to believe in me and believe in the dream.

I got back with the trainer I trained with for the Combine down in Florida. Moved to Florida for a bit. Rented my house out in Houston and I was just training. So going into ’17, we had Marc Trestman as our coach — the former Bears coach. A real intellectual guy. He put me on all types of spirituality stuff. Manifestation. Visualization. Learning how to forgive myself. Learning how to not be so hard when it comes to coaches. I had this thing with football coaches where I was always opposed and just wanted to fight and be like, “Oh, man, this guy’s trying to f--k me over!” He taught me how to let that stuff go and just play.

We ended the season 8-8, ran the table in the playoffs and we won the Grey Cup. I won Grey Cup MVP. And I was able to go back to the league. I told all the people at that organization, “Hey, this is what I want to do. I want to go back.” So, they released me. I worked out for some teams and I signed with Baltimore. Harbaugh gave me a shot. … I played with Ricky Ray but also S.J. Green. He’s one of the greatest CFL receivers. He’s like, “If you’re not read 1 or 2 or 3, you’re not getting the ball.” So I just learned that when I learned how to study, how to study football, and just put plays in my head. I could learn any playbook in four to five days. All football is, is personnel, formation, motion, assignment, technique and then you can be yourself. So all you have to do is take 70 to 150 plays and understand those five things, it’s really like a card memory game. It’s simple. It’s word association. It’s words with action — “What does this word make me do?” And there’s nothing new under the sun, so it’s just different names for different things. So when I got to Baltimore, I had this knowledge and I could see, “These guys are putting me on backside routes.” I could see the writing on the wall. It’s more stress than enjoyment so I said, “I’m going to finish my career out in the CFL.”

After Baltimore cut me, I went back to Vancouver. Helped that team get to the playoffs. The next year was my first year of free agency. Signed a huge deal to go to Montreal — by Canadian standards. About $220,000. I brought my family up. We had planned to have our second kid in Montreal. I don’t know if it was the language barrier or not but we went in and they sent us home and we ended up having our second son in our apartment. I delivered our second son. Pulled him out.

What?!

Posey: Yeah, bro. Crazy. I pulled him out. Finished that season off. I thought we were changing things around with the organization. We made the playoffs. They get rid of their GM. They get rid of their head coach that signed me to that huge deal. First thing that new GMs and coaches try to do is cut and save money and put their imprint on organizations. They wanted to renegotiate with me and cut my salary. I said, “Alright, cool. We can restructure.” And then he called me back and said, “We’re just going to cut you and bring you back.” I was like, “F--k you guys. I’ll just go to free agency.” So I ended up leaving there and going to Hamilton. Then, the pandemic came. That’s when I started the conversation off as where I wanted to start doing things differently. I ended up going to Hamilton and tearing my calf in my same leg I tore my Achilles on and thought, “Oh, this might be it for me. I don’t think my greatest impact as a human can be on a football field anymore.” You go from being the young guy coming into the CFL that can change the organization to walking into a meeting, and it’s “What’s up, OG?” You’re like, “Damn, bro. Is that a shot? I’m only 30. Chill.” Football flashes before your eyes so fast. So I decided to walk away and walk away quietly. I moved back to Columbus. I study communications. I do some radio and TV stuff around here.

Life has its ups and downs but I’ve always learned from my adversity and always come out better on the other side being honest and forgiving myself and learning the work will teach you. There might be hard days. There might be good days. Growing up in a single-parent home — and going through what I went through — I always wanted to be a great Dad and an awesome husband. God’s allowed me that opportunity here with my family. I hone in on those things. I follow you on social media, and know you’re a family guy, too. The best things in life are free. I get to indulge in those best things every day. My journey has been filled with adversity in front of a lot of people. Tearing my Achilles on national TV. Being suspended in front of Buckeye nation and the nation. Fighting through getting drafted, being replaced, being able to stand on the stage and be a Grey Cup MVP, I’m one of those people in life that won’t quit.

I hope people can learn from my journey and be inspired by just never, ever giving up on yourself and learning from your trauma and learning from your past and allowing it to harden you and blossom.

When you’re catching touchdowns in the Big Ten — and you’re the big man on campus — the vision for how the next 10, 15 years are going to go is probably a lot different. You’re probably thinking multi-million dollar contracts and glory and Super Bowls and notoriety. And then you take this path you laid out and you’re learning way more about life and way more about yourself than you ever would’ve if it went the way you wanted it to go.

Posey: Yes sir. Yes sir. Gifts come in multiple ways. You always hear people say, “The gift is the journey.” I can honestly second that. Just guys I came across who said they got inspiration from me — or saw what I went through — that stuff kept me going. Being an impact that way is the biggest thing I took away. I know my next phase of life, the money will come. The things I want to do will be there. I just have to continue to articulate and be who I am. I always embrace that.

With Ohio State, I can’t imagine what’s going through your head with all the transfer portal stuff today. All the millions of dollars being thrown around. It’s ridiculous to think what you, Terrelle and all you guys went through. At the time, it’s the No. 1 sports story. Your name’s getting dragged through the muck.

Posey: It’s crazy, man. Your pain can always be somebody else’s glory. I’ve invited it. I know our story has impacted NIL and a lot of decisions. When you look back at how we were dragged, we know we helped shape this NIL. We helped people realize how silly it was. To be honest, we had NIL deals all around the city. The irony of it all, my sophomore year, being a communications major, we had to do a 30-minute speech. I picked: “Why college athletes should be paid.” For a whole quarter, I researched. You had to have a problem. You had to have a solution. And you had to speak about it. So, I researched the problem. I understood how much people made from trademarks for the stadium. I understood what the video game made, what the jersey sales made and I came up with solutions. Trust funds and things like that. And what the Olympic committee does for amateur athletes, so they can go and compete in college. I had all these solutions for ways college kids can be paid. Through the irony of it all, I ended up not giving a f--k about the rules anymore. The veil was removed from my eyes. I could see what was going on. Yeah, it bit me. I lost a lot of money. I’m happy I uncovered that knowledge. I’m happy I learned that because — on our journey — me and those other four guys have impacted guys like Bijan Robinson or TreVeyon Henderson or CJ Stroud who’ve been participated in (NIL deals). Pain is glory. That’s what I teach my sons. It’s the truth.

But how difficult is it in the moment? Because that was a totally different frame of mind for everybody involved. Like you said, you were getting talked to, looked at a certain way on campus? When you got in trouble, was it difficult to deal with?

Posey: I remember I called my Mom and said, “All these people are saying stuff about me.” She’s like, “People are talking about you on campus?” I’m like, “No! On this app called ‘Twitter!’” We had to be some of the top 20 first people trolled. That was that social media anxiety. That social media depression that we battled against early — before it was even a thing, before we even knew that a social app could cause this. That’s what we battled.

So you weren’t worried about getting in trouble when you’re selling your stuff? I guess you just didn’t care.

Posey: We kind of got to a point where we didn’t care.

You did your research.

Posey: At the time, selling your memorabilia wasn’t illegal. The NCAA had a running business plan that adjusted from our case. After us, kids weren’t allowed to get their rings or their jerseys until they graduated. But before that, there were no rules against selling your own things. And the case wasn’t about tattoos. It was that we sold our belongings to the guy who owned a tattoo shop. If you really look at the case, that’s what it was about. But they dumbed us down. They ran with that story. That’s why when I hear stories, I always want to hear the truth and what really happened because the media’s powerful. They can create narratives that the public has to believe because it’s “breaking.” If you really dig into our case, it was a Name, Image and Likeness case that we understood.

Shouldn’t there be some type of formal apology from the NCAA? I feel like there should be some sort of reckoning?

Posey: That’s why I talk around it and won’t go too much more into detail but we’re working on a documentary. We’re working on getting our story out there and really diving into it. All five of us have agreed to work on this. It’s something we’re working on. We think the time is right. We think it’s relevant. Being here around Ohio State and knowing we have their blessing to speak on this, we’ve been hashing that out. That was part of 2020, one of the projects I really wanted to work on and bring to light — our journey and how it impacted us over the years, over the decade since it happened.

Tearing your Achilles. That sounds like the worst possible injury for a football player, that feeling of a tendon recoiling up your leg like it’s the blinds on a window.

Posey: It’s the kiss of death for a lot of athletes. It’s one of your most powerful tendons. It takes so much force.

To come back from that, it’s right at the start of your career, too. That can end careers. How did you do it?

Posey: That’s where my health-tech start-up and the motivation for that came up. Just learning about my body and reprogramming it. I went through small intestines, big intestines, stomach detoxes. I got everything out of my system. When you go through an injury, depression takes over. It can suppress your hormones and your testosterone. So doing that flush naturally, I had to restart my hormones so I can upkick the recovery process. I made it back from that in six to seven months. Which is normally a nine- to 12-month rehab. Learning about my body and learning about the foods that go with my body. The nutrients that go into my body. And taking this personalized medicine route, I realized that when I came into the Combine, my blood type was still showing that I was immune-deficient in Indy. After I went through all of that stuff, I changed the course of my blood and reprogrammed my body, so when I got to the Jets and did my blood test, it didn’t show any deficiency in my immune system. I basically healed myself from diet, nutrition and the recovery things that I did to where it was like, “Wow. I helped my immune deficiency by restarting my system. This is knowledge the public should have. This is knowledge we should be able to share with people.” That was the motivation behind my health-tech startup. I tried to use all of my pain for glory in some way.

At every turn, you find a good in a bad. You didn’t see eye-to-eye with O’Brien in Houston you said?

Posey: I wasn’t the type of receiver he wanted or maybe he had painted “bad character” from college. I didn’t know. That’s one thing I learned, too. Every coach who has told me “no” has been fired, or every GM that didn’t want to mess with me has been fired. So you can’t really take anything personal. Everybody has an agenda. There’s man-made mistakes. There’s man-error in everything. So guys who go through the game and say, “Oh, this coach doesn’t like me. This didn’t work out.” Yeah, I hear you. Just know that coach has a time limit on his job, too.

That was something you had to work through — trust a coach, work with a coach, not taking it personal. It was until Trestman in Canada that you were able to have a good relationship with a coach?

Posey: Yeah, man. Learn that it’s a working relationship. There’s give and take. And a championship and an MVP came out of it.

What was that moment like, when you’re the Grey Cup MVP and you’re able to exhale and enjoy vindication after everything?

Posey: It was monumental. I had to really sit back. My wife was crying on stage, and she was like, “Why aren’t you crying?” Because I had learned about manifestation and I had the picture of me standing on the stage holding the Grey Cup. I pictured it night-in and night-out. I really got into meditation and envisioned those things. Not to say it’s magic, but there’s a book, “Into the Magic Shop” by James R. Doty. I read it that year and learned that you’ve got to see things before they happen. That’s what I had to learn. We celebrated that night and we flew back. I got home to my apartment before my wife and my kids got home. When I got there, I just busted out crying. I thought about my journey. I had that moment with myself, like “What is happening?” There was a pause in time where I had to think, “Life is beautiful.” When you think it’s down and it’s not great, great things can happen. That’s when I learned to use everything that year. I love 2017. It was a great year for me.

And I can’t forget this. You delivered one of your children? How? We have two kids. I have no idea how anyone could do that on their own in an apartment.

Posey: My wife quarterbacked everything. She’s a trooper. She’s amazing. I was just able to be calm and she walked us through. “Grab the blood pressure monitor. Grab this. OK, now that the baby’s out, let’s take the placenta out. We cut the umbilical cord.” It was amazing. She was awesome.

I don’t know how you have time, but it sure seems like you’re a family man. Family’s so important to you.

Posey: Yes, it is.

If it’s casual conversations like this you prefer, feel free to sift through the Q&A archives at Go Long. We’ve chatted with the likes of Bruce Smith, Drew Bledsoe, Darren Woodson, Ronde Barber, Trent Dilfer and many more about football and life.

Great story, Tyler! I am excited to see what DeVier does going forward! What a cool guy and great story. I will be eagerly awaiting that documentary too...it's so nice to see athletes who put their bodies and minds on the line finally getting SOME money. And when the floodgates open after the inevitable Supreme Court decision saying players need to be paid, it's going to be wild!