How Dion Dawkins, the "ShnowMan," became the soul of the Buffalo Bills

There's nobody else like him at his position. Here's how Dion Dawkins became larger than life in Buffalo... he's not done yet, either.

BUFFALO — In walks Dion Dawkins and, no sir, this is not how offensive linemen are supposed to walk and talk.

On this corner of Chippewa Street downtown, right into Bocce Club Pizza, the 6-foot-5, 320-pound man is a lightning bolt of energy.

His hair’s dyed blond. His nose is pierced. His arms are draped in tattoos. He’s rocking red ‘n purple Nikes, light blue shorts, a t-shirt with an ice cream cone that reads “So icy” and Dawkins doesn’t so much walk as he does glide. The team captain who’s always dancing, always reminding you he’s the “ShnowMan” is everything you’d never expect from someone in his profession.

And yet, none of this is forced. This is no tacky, scripted act.

This is, quite sincerely, who Dion Dawkins is.

Inside, the AC unit blares as the steady bass to a soundtrack of pizzas sliding into ovens and orders being shouted. Dawkins begins this visit with Go Long by saying he knows for a fact that this liberating sensation coursing through his veins is rare, that other NFL franchises “shelter” their own players. He knows guys who feel like they’re walking on eggshells 24/7. Especially linemen because linemen are supposed to be nothing but gigantic oafs of flesh and bones that block. Only block.

In Buffalo, he claims this is not the case.

“Whether I was a long-snapper or a f------ kicker or anything, here, they allow me to be me,” Dawkins says. “And with them allowing me to be me, I’m me at full effect. So when you see the swag, when you see the personality, that’s me truly being me. Because they open up those gates. I don’t have to sugarcoat shit. I don’t have to f------ hide. I don’t have to live in a blanket. This is Dion and you’re going to get the true Dion. I care. I f------ love people. Sometimes, I care too much.”

Who is the “ShnowMan” today? A free spirit who’ll break into choreographed dance after catching a touchdown in Foxborough. A quote machine who compares a win to eating mac and cheese, saying it gets all “nice, wet and juicy” when he stirs it up. Of course, Kraft then slapped his full quote on the side of its box and Mooney’s Sports Bar & Grill in Buffalo introduced the “Shnow Mac.” He’s a man with style — you’ve likely seen him with blinding chains around his neck — who doesn’t so much use words as yelp and screech and create his own language on his IG story.

You’ll hear a “Skeee!” one day. Maybe invented words with “Shnow” blended in the next.

And nobody raises an eyebrow. Nobody smirks.

When, you know, a few Bills players didn’t exactly feel this way about Sean McDermott on their way out the door.

The best way Dawkins can explain the atmosphere in Buffalo is through more analogies. Think back to the last fight you had with one of your friends. Upon making up, was it still weird? Still a little… off? He insists players never have that feeling here.

“You never have that smirk of a feeling, like, ‘Mmmm, f--- that guy,’” he says. “Like, ‘Mmmm, he just needs to worry about ball. Mmmm, he’s doing too much.’ You can be yourself. Be you. You’re going to mess up. You’re going to do good. Who cares? As long as you can feel free playing and show your personality and wear a dark visor and be swaggy, do your thing.”

Or, think back to your upbringing. Maybe your Dad took you hunting as a kid, he explains. You trudged through the snow. You sat in the cold for hours on end. You… wanted to be a basketball player instead.

“And you knew that your father didn’t really want you to play basketball,” Dawkins continues. “You can feel that energy from your father. Here, that energy of negativity — of not allowing you to be yourself — it doesn’t exist.”

Instead, the Bills inked Dawkins to a four-year, $58.3 million contract this time last year and went 13-3.

Instead, Dawkins’ energy has become the entire team’s energy.

A team hijacking the Steelers’ mojo during “Renegade” in 2019 and breakdancing to MC Hammer before the franchise’s first home playoff game in 25 years in 2020 should now hope to win it all in 2021. That’s the expectation. All along, Dawkins will make sure everyone remembers to be their authentic selves 24/7 because he knows that even though this sport inherently turns players into mute cogs in a machine, it’s also a sport played by human beings. It’s fueled by emotion. Wins and losses aren’t spit out of a mathematical equation on Excel.

One hour into this conversation, it hits Dawkins — his larger purpose, the legacy he’ll leave in Buffalo and beyond.

“I’m just trying to change the culture for all of the other guys that are coming,” Dawkins says, “that it can be cool to be an offensive lineman. You don’t have to be a big, sloppy fat dude to protect the quarterback. No! You can be a dope, swaggy dude.”

With that, his mind drifts back to growing up in Rahway, N.J.

“Nobody dreams, ‘I want to be an offensive lineman!’ Everybody dreams of catching the football and scoring touchdowns and dancing in the end zone and tackling the quarterback. Nobody says, ‘Oh, I just want to be a blocker.’ Nah. Even bigger dudes in their progression of life, if you’re a bigger dude in high school and everybody else is skinny, you go with the emotions of insecurities. Like, ‘Damn, I’m fat. Everybody else is skinny. He plays wide receiver. He’s skinny. He’s getting all the girls.’ Big guys are never comfortable expressing themselves because they were sheltered.

“They were, ‘Oh, we’re just the fat guys blocking.’ But now? Just be open.”

Seconds later, locals start recognizing Dawkins.

One by one.

Six fans ask Dawkins for a picture in a 10-minute span and, each time, Dawkins goes out of his way to make small talk and pose for a photo without hesitation. He’s even run into half of them before. Then, one woman ordering pizza recognizes Dawkins in the corner of her eye and loses her mind. “Oh my God! Oh my God!” she squeals. “I can’t even stop shaking.” They take a picture together, Dawkins says “enjoy your day” and we pick up our chat. Upon hearing that this writer’s sister-in-law is a Bills superfan, he asks for my phone, turns the camera on himself, hits record and delivers a 29-second video that’s nothing shy of outrageous.

That’s the ShnowMan, the soul of this Super Bowl contender.

This isn’t all by accident, either.

“My life,” he says, “has been a rollercoaster.”

The Crossroads

Since this is who Dion Dawkins genuinely is — vibrant, gregarious, rebellious — the “rollercoaster” nearly careened off tracks when he was young.

He doesn’t sugarcoat a thing, no.

At the tail end of middle school, right into high school, a 13-year-old Dawkins went through what he calls a “stealing phase” for absolutely no reason. He’d swipe cell phones. He’d steal video games at Blockbuster. He really had an obsession with bicycles. Some, he’d ride. Others, he’d tear apart to build his own souped-up bike.

“Being a rebel,” Dawkins says.

Word spread, too. When hulking NFL defensive tackle Antonio Garay suffered an injury and returned home to Rahway, he heard all about Dawkins teetering on the edge. Heck, he saw it himself. Dawkins — a sophomore then, a “big, dopey kid” — too often zipped around the local park in a dirt bike. He knew he was stealing iPods, too. Yeah, Dawkins possessed a “bubbly” personality, Garay says, but he was super immature.

Whenever Garay went to shake his hand, he was instead engulfed in a bear hug.

“And I’d say, ‘Get off me! Where’s my wallet at!?’” Garay recalls. “Back then, he’d get in dumb shit. I would get on him, ‘Why are you doing dumb shit like that?’ He was just immature. It wasn’t like he had to do it for any particular reason. He was just a big goofy kid. I’d look at him like, ‘Damn. Are you going to get your shit together?’”

Then, he’d tell Dawkins they weren’t boys and that he should shake his hand and look him in the eye instead.

That was one side of him.

There was another side, too.

At age 13, he also became the “ShnowMan” in his neighborhood. The same kid who loved to steal also loved to help out everyone he could. The morning after snowstorms, Dawkins would go door to door asking strangers if they wanted their driveways shoveled. It was a different time then, he admits. (“Everyone wasn’t on pins and needles.”) People had no problem giving a kid keys to get their ’94 Suburbans and ’97 Tahoes warmed up while they got ready for work and, no, Dawkins never considered stealing his own neighbors’ vehicles. He wouldn’t take it that far.

Soon, strangers became friends. They couldn’t wait to see Dawkins at their door in the AM.

For starters, he was beyond polite. After introducing himself, Dawkins gave folks a few options — Do you just want a walkway? A path for your car tires? The full driveway? With each tier, he charged more money. Some people would be in a rush. Others would have Dawkins shovel the entire driveway. Typically, the base price for a walkway was $25 while the whole driveway would jump to $50.

Money added up. Quick.

“People back then were so nice,” Dawkins says. “So I would do it and, literally, it became a relationship to where when I would come they’d have hot chocolate for me. They would have breakfast sandwiches. It was like, ‘Damn!’ …. I would come home with cash. Hundreds, easily. Cash, cash, cash, cash.”

His business became so popular that Dawkins eventually needed a friend to help him and, together, they’d knock out 10 to 15 houses at a time.

School was cancelled, too, of course. They’d have all day.

And, so, his life was at a crossroads: Which Dion would enter adulthood? The kid taking or the kid giving?

The tipping point came his junior year of high school, when that kid taking went too far.

Into high school, Dawkins had a teacher he really despised. A teacher he calls a name we’d rather not print here. A teacher who also had a habit of leaving her purse near the front door of the classroom. One day, when she wasn’t looking, Dawkins reached in and took her wallet. Yet when he tried to order Domino’s for all of his friends on her credit card later that day, it didn’t work. She already had the card cancelled. He was busted. And when Dawkins witnessed how much this all affected her, something inside of him changed.

He apologized, and she told him it wasn’t so much the credit cards she missed but the medical cards.

He apologized once more, gave his teacher a hug and she started crying uncontrollably.

“That,” Dawkins says, “turned it all around.”

Others noticed, too. That same year, someone on Garay’s family softball team asked him if he knew who this Dion Dawkins kid was. Garay braced for the worst and this person told him that Dawkins apparently was interested in his girlfriend’s daughter. So interested, in fact, that he wrote her a letter expressing his feelings and — upon meeting him — Dawkins gave this gentleman a strong handshake while looking him square in the eye.

Which absolutely put the biggest smile on Garay’s face.

Dawkins was able to grow, he adds, “without losing himself.” That kindness won out. His uncle and mentor, Eugene Napoleon, says it’s in Dawkins’ blood to be so authentic, so inherently good. The maturity was bound to kick in. Dawkins realized he needed to quit hanging out with one group of kids, keep hanging out with another group of kids and the latter remain his best friends to this day. Napoleon points to a different interaction with a teacher, too. At age 12, Dawkins once went out of his way to cheer up a seventh-grade teacher who had just lost a child at birth and was bedridden at home.

Patricia Volino-Reinoso loved Froot Loops so that’s what Dawkins brought right to her doorstep.

“That’s the kind of kid that he is,” Napoleon says. “Most kids don’t even think about that on that level. There’s something about him that’s always endearing. He has a really big heart. It’s not for the media. It’s not for any adulation or somebody else patting him on the back. He knows it’s more important to do the right thing than the wrong thing. He knows that if he can inspire change in others, he’s going to do that.”

Napoleon helped Dawkins get into Hargrave Military Academy to improve his grades, then Temple University to make something of this whole football thing. When the school’s head coach, Matt Rhule, first laid eyes on Dawkins, he told Napoleon he never coached anyone built like this even as the New York Giants assistant line coach.

And as he evolved, Dawkins developed another trait: Loyalty.

Fierce, unflinching loyalty.

This trait nearly crashed the rollercoaster for good, too.

The breakthrough

All he remembers is the distinct feeling that his life was over.

All progress, all dreams… vanquished.

Sitting here at a pizza joint, the 27-year-old Dawkins thinks back to sitting somewhere else at age 20: Jail.

For two days, he toiled in his darkest of dark thoughts inside a holding cell. If forced to spend “X” number of days in a Philly prison, Dawkins knew he could defend himself. Beneath this quirky veneer is a fighter who doesn’t back down. Rahway hardened him. Still, Dawkins knew how that veneer would be perceived by dudes in prison who were, undoubtedly, harder than him.

“I was a big, light-skinned kid with blond hair,” Dawkins says. “So I’m thinking, ‘Damn, I’m about to be in prison and go into jail with these grown men that probably think, ‘He’s just some f------ kid.’ I’m thinking I’m going to have to go in there and fight again! I was prepared for it. Whatever happens, happens. And then I was thinking, you can get charges while being in jail, too. So imagine if I went in there and had to fight again to defend myself and get more time… off of one incident.

“All of that stuff was going through my mind.”

With play-by-play precision, Dawson then relives the “one incident” that sent him to that cell.

He doesn’t drink. He doesn’t do drugs. He won’t even pop an Advil which, come to think of it, is insane for anyone playing the most violent sport on earth. Nothing was in his system forcing him to do anything that night in January 2015. A junior at Temple, Dawkins went to a party at the now-defunct Club 1800 just to have fun and he came to this particular party in this particularly unsavory part of town with a teammate (Chris Myarick) who he remembers being the only white person in attendance. A few others got in Myarick’s face to “start some shit,” he says, which led to some pushing, shoving, trash talk and initially, Dawkins didn’t think much of it.

Until…

“Out of the corner of my eye,” he says, “I see my teammate fall. The motion of a hand and my teammate falling. He fell. So, I felt the need to defend him.

“I just reacted. Had to. Out of defense of my teammate. That’s my job — I’m a protector. That’s my job. That’s been my life. Even my major in college was criminal justice. Everything is protect, protect, protect. So, it’s just natural instinct, man. Natural instinct.”

In this moment of fight-or-flight, Dawkins didn’t think twice and a brawl broke out.

The victim reportedly suffered a broken orbital bone and a concussion. With a warrant out for his arrest, Dawkins turned himself in, spent those two days scared to death and, swiftly, was suspended by the football team. Here, he points across the street to a building about 30 yards away. That’s how close Temple’s practice facility was to his apartment in Philly. From the fifth floor, Dawkins watched someone else start in his spot through spring ball.

An NFL future evaporated before his eyes. His reputation? Shattered.

“I thought my life was over,” Dawkins says. “The guys are going through their chants and I’m like, ‘Damn, I’m supposed to be out there. I f----- up. I f----- up bad.’ So I was thinking to myself, ‘I have to really watch everything that I do.”

One of the first people to help was Garay, who drove to Philly as soon as he heard about the arrest. Garay saw the stress eating away at Dawkins firsthand and, as a seven-year vet himself, tried to get Dawkins’ mind right, tried telling him repeatedly that he did the right thing. He jumped in to save one of his teammates and, dammit, that’s an admirable quality.

Dawkins told Rhule his side of the story and the tide started to turn. Rhule believed him.

His life was most certainly not over. In fact, Rhule also liked the fact that Dawkins’ natural instinct was to stick up for a teammate. What could’ve destroyed Dawkins only emboldened him, only grew to define him. A judge dismissed three of the assault charges, Dawkins recalls paying a fine close to $50,000 and, that point forward, he locked himself in his room every weekend to watch film. Whenever Garay called, Dawkins told him he wasn’t risking a thing.

This all sharpened his focus even more.

Temple then went 10-4 in back-to-back seasons.

The school only has one other 10-win season in its 74-year history.

“Because he believed me, I am the person I am today,” Dawkins says of Rhule. “Most of the time, when that stuff happens, their career’s over. Like, if that happened with somebody at Alabama? Their career is over. Done. Over with. But they stuck with me.”

Thinking back to that party once more, Dawkins can only shake his head. Apparently, per the law, he was supposed to watch his friend get bloodied, beaten, do absolutely nothing and run to the cops to press charges. What a world, eh? He won’t use the name of the person who instigated this all because Dawkins says that’s exactly what this kid would want. He only calls him a “clown” and claims this is someone who had a long history of antagonizing athletes at Temple. And the sad irony of this all is that Dawkins isn’t even close with Myrarick anymore. He says his friend was scared to stick up for him in court.

Not that any of that matters now.

Temple’s belief fed more belief in himself and, as Napoleon adds, Dawkins has always been a “protector” who despises bullies.

“Had it not been for Dion, his teammate would’ve gotten pummeled,” says Napoleon, a former West Virginia running back himself in the late 80s. “You’re trying to help your teammate and save him. In lieu of that, it’s ‘I’m going to take the brunt of it because of my size and because of who I am.’ The most important thing to him was to get his teammate out of there safe and sound. So once again, he’s thinking about somebody else and not really even thinking about himself.

“He could be a totally different personality. But why? If that’s not authentically you, why?”

The Bills believed. They made Dawkins the 63rd overall pick in the 2017 draft. The team’s area scout then, Marcus Cooper, was into Dawkins early and then former GM Doug Whaley, director of personnel (and current Go Long Podcast co-host) Jim Monos and McDermott all got on board to make the pick. As Monos has said, he loved Dawkins’ personality. He can still picture Dawkins dancing in pregame warmups at Temple. This was a swagger the Bills knew they needed.

Of course, 48 hours later, McDermott fired the front office and immediately took a hacksaw to the roster.

As players left, no, they didn’t have the nicest things to say about the new head honcho in town, either. Sammy Watkins, for one, said McDermott was waging a “mental war” to get him to explode. Others, off the record, said much worse. The theme? He was too militaristic, too serious which, uh, wouldn’t seem like the best work environment for the “ShnowMan.” Asked about his initiation to pro football and Dawkins admits he wasn’t his fun-loving self the first few months but that was because he felt the need to shut up and prove himself as a player — first — to vets Eric Wood and Richie Incognito on the offensive line.

Once he did? He busted out of his shell.

“If you ball,” Dawkins says, “you can have the personality and do the things you want. If you’re just a personality — a bullshit guy — you’re not helping us win.”

Incognito remembers fearing exactly that when the Bills drafted him. He and Wood both were skeptical of this kid shouting “You already Shnow!” on his IG account. Yet then, Dawkins brought the same energy, same enthusiasm and same work ethic every single day. That’s the best way Incognito can describe him, that he’s “consistent.” And he points to a Week 2 loss at Carolina as the NFL breakthrough. Thrown into action when Cordy Glenn suffered an ankle injury, he says Dawkins was in “full panic mode.” And on a critical play late — right after Incognito told him who to block — Dawkins screwed up. Badly. He tried tagging someone else, the play blew up and Buffalo lost, 9-3.

The next day, Incognito roasted him.

“I was yelling across the locker room, ‘You don’t shnow shit! You don’t shnow what to do! You don’t shnow anything!’” Incognito says. “I let him have it. We went and worked out and then he sat by my locker and was like, ‘What do I have to do to play?’ And I said, ‘Listen, you have to be prepared for all of these scenarios. You have to watch guys like me and E-Wood. We’re constantly taking notes. We’re constantly asking questions. When they put this gameplan in, you have to know all of the ins and outs of it. If one of those oddball plays gets called on fourth and 1, you have to know exactly what to do.’ And he said, ‘I’m going to study. I’m going to prepare.’”

Dawkins never looked back.

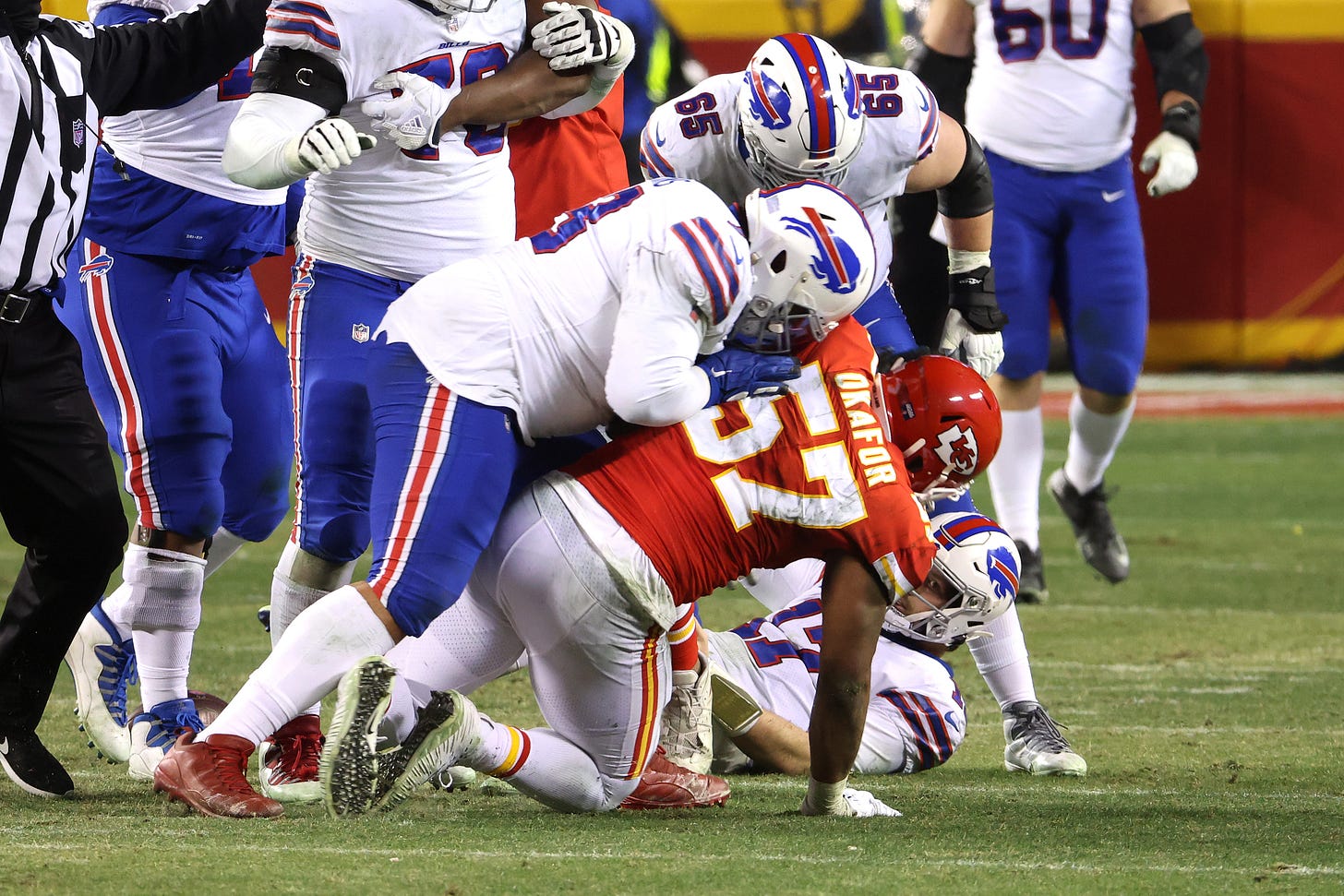

He’s now entering his fifth year as the starting left tackle and is permitted to dance all he wants. All of these Bills are dancing right with him, too. He’s giving the team the attitude it needs to capture its first Super Bowl ever and showing all linemen ‘round the NFL that it’s OK to have some fun. He’s still retaliating, too. You remember the sight. Arrowhead Stadium might as well of been a nightclub in Philly with three minutes left in the AFC Championship. The Bills’ season was all but over, but it didn’t matter. When Josh Allen tossed the ball at the head of Chiefs’ defensive end Alex Okafor and Okafor then got in the QB’s face, the Bills’ linemen attacked.

In came Jon Feliciano to light Okafor up. And in came Dawkins to shove Okafor in the head.

He definitely had flashbacks to ’15.

“It’s the same f------ thing,” Dawkins says.

Then, he nods as if daring anyone to try him.

The Dawkins Effect

The first time you hear a first-year head coach fail to harp on culture in front of a mic, hell will effectively freeze over.

Granted, fans crave such culture talk like oxygen but, too often, it’s a nebulous term that amounts to jack squat.

And there was McDermott from ’17 to ’18 to ’19 filibustering on and on about everyone needing to “trust… the… process.” He beat those three words into the heads of locals to the extreme of Billy Fuccillo roaring “Huge, Buffalo, Huge” and the Xtreme Discount Mattress Guy promising to sell mattresses “for less… a lot less” and Russell Salvatore telling you to be his guest and let him “do the rest.” Thus, you couldn’t help but wonder what any of this culture talk even meant. Stoic coaches past have said the same things only to never win over the locker room i.e. nearly every Bill Belichick disciple.

Four years in, the players who’ve lived this “process” repeat that this “culture” is all about coaches letting them being themselves. On his Happy Hour appearance with Go Long, wide receiver Isaiah McKenzie dug into exactly what this looks like day-to-day. It’s a delicate balance, too. Rex Ryan let players be themselves a smidge too much. His lawlessness came back to bite Buffalo in the ass. Now, it’s clear that this culture and this locker room has an undisputed deputy: Dion Dawkins.

The ShnowMan has emerged as the voice to follow around here.

After everything, he is himself — “to the fullest.”

“When it comes having friends, I don’t know how to be a half-friend,” Dawkins says. “If you’re my friend, I want you at my wedding. I want you standing there with me. I’m ride or die. I try to show that in the things that I do and how I talk to people and whenever I’m smiling and dancing.

“That’s what I strive for — to be as true as I possibly can and to let people see me being organically me. Without any bullshit around it. Without any sugarcoat. All that shit is over with. I’m already at the next tier of my career and I’ve been the same way since Day 1. So as the world sees, I’m not changing for anybody. You’re going to get the smile. You’re going to get the dances. You’re going to get the laughs. You’re going to get the f--- bombs, the shit, the ass, all type of stuff. This is me. This is just me. I truly think football is only a small, small, small, small, small, small, very minute portion of my life. Very minute. People will talk about Dion the football player but they’ll also talk about Dion the person just as much.

“That’s what I strive for, to have a Hall of Fame person career just like I want to have a Hall of Fame player career.”

He’s not sure what will go into that quite yet but is doing everything he possibly can in his communities.

In Rahway, he organized a food drive last April right at his old high school.

In Buffalo, he celebrated “716 Day” with a Christmas in July event to help small businesses.

The last thing Dawkins ever wants to do is turn tribal like so much of society. Nowadays, most people tend to surround themselves only with people of the same political beliefs, same skin color, same upbringing, same social class, etc. That’s never been Dawkins, nor will it ever be. He forms his own opinions based off his own experiences. You bet the kid who loathes bullies is unbelievably tight with the player you might’ve written off as an all-time bully. Dawkins and Incognito still talk all the time. Way back in ’17, when Yannick Ngakoue accused Incognito of using a racial slur in Jacksonville’s playoff win over Buffalo, Dawkins was the loudest voice defending his teammate. They’ve even vacationed together.

To Dawkins, far too many people think in a box. He still remembers people in his Rahway neighborhood disparaging the Indian community — and their words only drove him to try Indian food, to learn as much about their culture as he could. He’s determined to now travel and learn about as many different cultures as he possibly can. So far, he’s been to Brazil, Columbia and the Dominican Republic. Soon, he’ll head to Africa, Dubai and Thailand.

“Make up your mind for yourself!” he says. “Don’t let somebody else make up your mind for you.”

That attitude’s been contagious in Buffalo and, now, Dawkins is thinking even bigger than football. He’s thinking of other kids out there about to swipe their teacher’s wallet. He wants to affect that life on the brink.

No, don’t count on Dawkins changing for anyone.

He’ll dance with his dog in a clip for his aunt’s music video, a two-step that still cracks up Uncle Eugene. (“He doesn’t want anybody down,” Napoleon says. “He doesn’t want anybody gloomy or doomy. When you see him, you know you’re going to get a good laugh.”)

He’ll get into every extreme sport he possibly can whenever his football career’s over. This day, he pictures himself biking straight down a steep mountain. He’d love to snowboard, too.

He’ll keep his two kids at the forefront of his mind. Their arrival took his focus to an entirely new level. (“Once you’re a Dad,” he says, “you get that crown of — ‘Provide.’ It just clicks.)

He’ll take football seriously, too. Incognito sounds like a proud dad now, calling Dawkins “a wall” of a left tackle who never gets beat and absolutely deserves to make the Pro Bowl.

He’ll probably tee off on another opponent after the whistle, too.

Where this all takes the Bills is anyone’s guess.

For now, he’ll finish his pizza. Not too fast, though. He doesn’t want to burn his mouth. He wants to enjoy it. And when he’s done? Dawkins is in zero rush. He strikes up a conversation with one more stranger ordering food and plans to say hello to two more friends across the street.

He hopes it’ll make their day, too.

“I try to bring joy,” Dawkins says, “to everybody.”